On 26 December 1924, Gabriel Cromer stood in front of the Société française de photographie and made an impassioned proposal: We must create a Photography Museum. A noble proposition, one infused with a desire to educate, a sense of patriotism, spirited urgency, and perhaps a touch of vanity – the museum would centre around his own incredibly detailed collection of photography history.

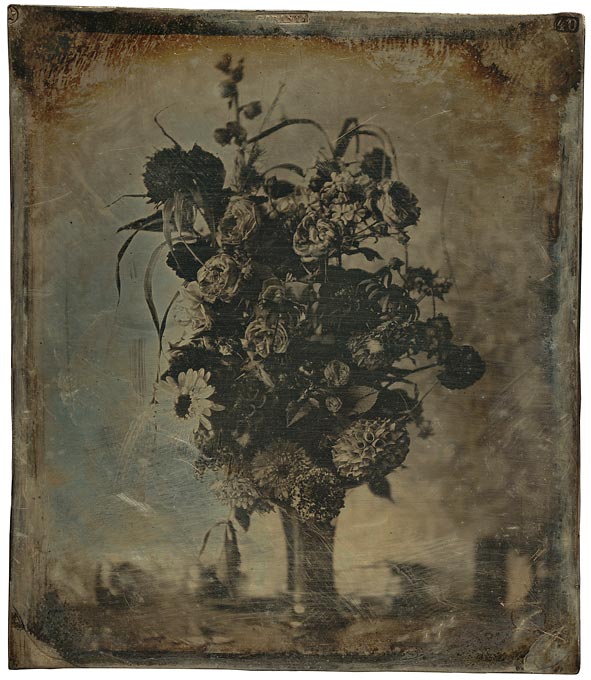

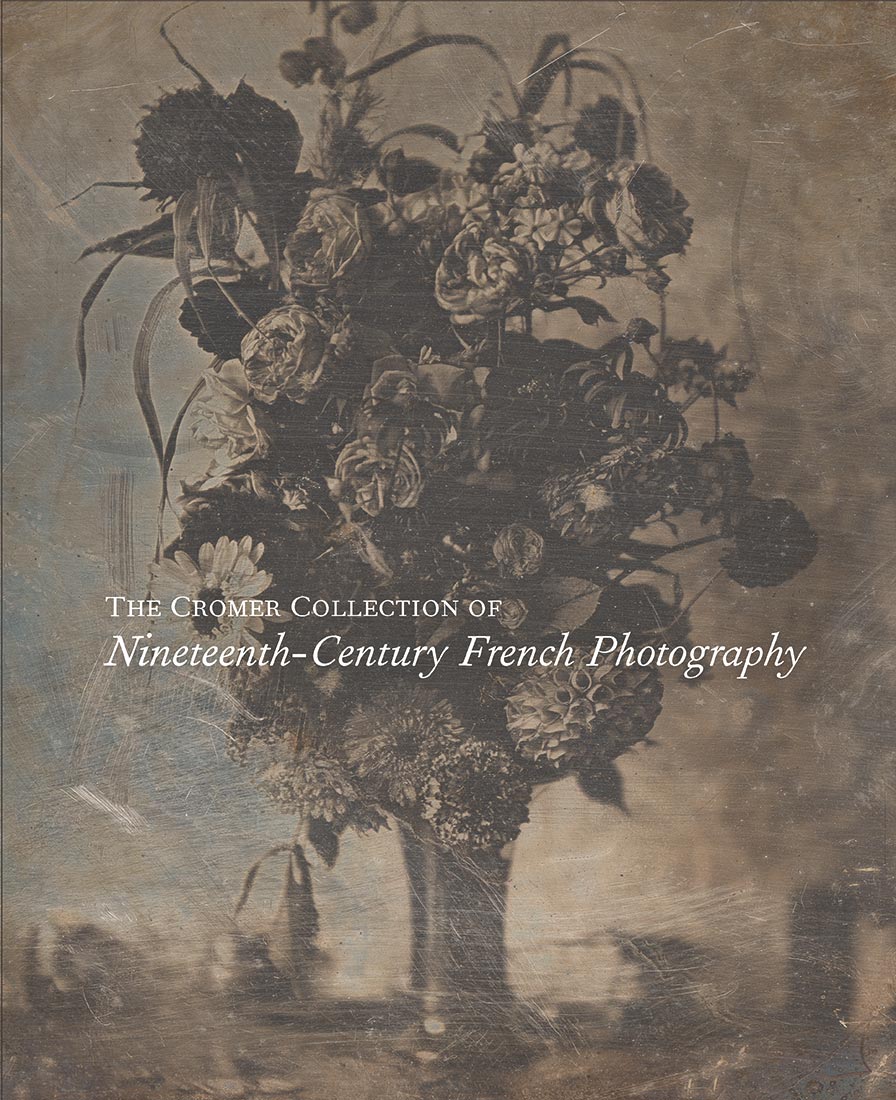

Nearly 100 years later, it is quite fun to imagine what Cromer might make of The Cromer Collection of Nineteenth-Century French Photography, published earlier this year by Yale University Press, in conjunction with George Eastman Museum, where the majority of his images and objects are housed. It is a sumptuously illustrated hard-cover tome of such import that it seems wildly overdue; in reading through the book’s six meticulously researched essays, we can deduce that Monsieur Cromer would certainly agree.

Bruce Barnes, the Ron and Donna Fielding Director at George Eastman Museum, introduces Cromer as a collector par excellence in the book’s foreword, setting out a brief history of how the lion’s share of the collection came to reside in Rochester, New York. The six essays that follow (three by American scholars, and three by French) weave together Cromer’s collecting impulses, the collecting circles in which he competed, and the vision of the collection’s ultimate American buyers – not to mention what became of the bits and bobs that were left behind in France (unbeknownst to the collection’s new owners).

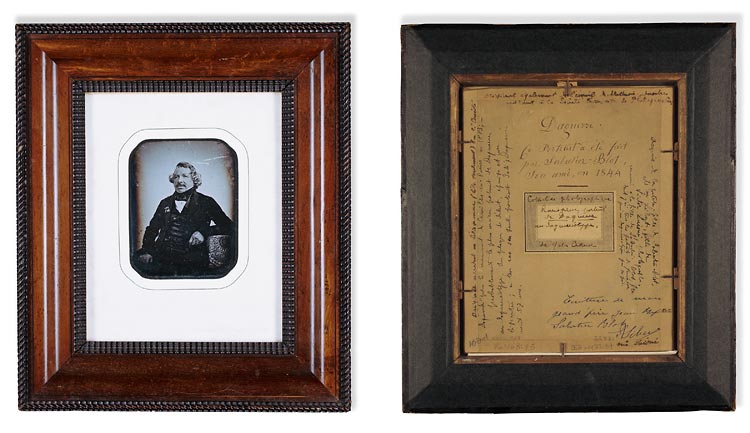

Cromer was born in Rethel, northern France, in 1873, to a well-off family, and was raised in Paris. In the first essay of this catalogue, A Story of Labels: Gabriel Cromer, the Photographer, the Collection, and the Museum, Eleonore Challine introduces us to a man who “as a person of private means […] practiced photography as a learned amateur.” The biographical details are less important here than Cromer’s collecting processes – his penchant for delicately labelling each of his objects with adhesive paper (most notably, the famous 1844 daguerreotype portrait of Daguerre himself, by Jean-Baptiste Sabatier-Blot, which is beautifully reproduced, recto and verso), or his intense dedication to understanding the innerworkings of photographic equipment used by early masters. He belonged, as Challine writes, to the category of historian photographers.

Anne de Mondenard goes on to introduce us to ‘The Circle of Collectors around Gabriel Crome’r in her essay A Fraternity of Rivals. It is here we get a feel for his collecting impulses – the hunt for daguerreotypes in Montparnasse, or negotiating the acquisition of Alphonse Giroux’s 1839 daguerreotype camera, complete with Daguerre’s signature on its label plate. Competitors crop up in salons and exhibitions – names like Barthélemy, Sirot, Gilles, and Bonney.

During the last decade of his life, Cromer worked to convince the French government to establish a national museum dedicated to photography – they declined his offer to purchase the collection for 320,000 francs (and gift him a curatorship in the process). In 1934, Cromer died, and the fate of the collection was entrusted to his widow, Marie.

Enter the Eastman Kodak Company, who knew quality when they saw it. Heather A. Shannon takes us From Paris to Rochester in her essay detailing Eastman Kodak’s 1939 Purchase of the Gabriel Cromer Collection. After receiving a lowball offer from the French government, Cromer’s widow Marie arranged for the sale of the collection to American buyers Eastman Kodak – from there, it would go on to become a foundational part of today’s George Eastman Museum. Shannon does an excellent job of parsing the motivations of various Eastman Kodak players, and the keen interest in how Cromer’s collection could serve as a “pre-history to Eastman Kodak’s technological achievements.”

The collection of images and objects arrived in Rochester, New York in March 1940. George Eastman House opened to the public in 1949 under the curatorship of Beaumont Newhall, and 70 years later, in 2019, a three-year cataloguing and digital imaging initiative reached its conclusion, sharing each item in the Cromer Collection in the museum’s online database. Ellen Handy examines Newhall’s relationship to the Cromer Collection in her essay A New History of Photography, and relays the tensions present in Cromer’s compilation of photography history with Newhall’s own model.

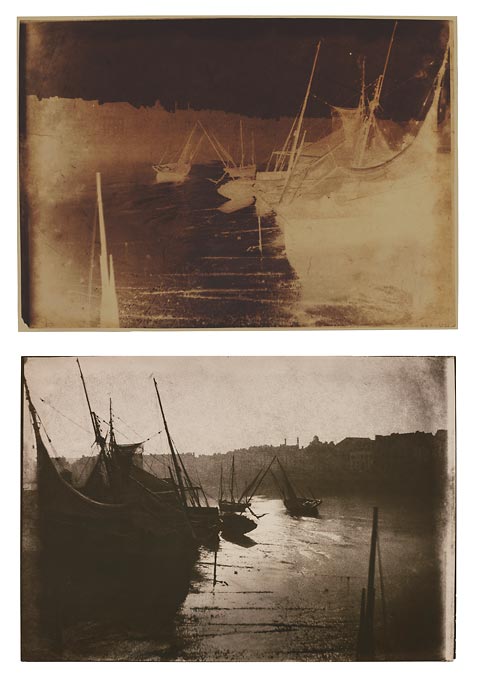

The book crosses back over to France for Sylvie Aubenas’ essay detailing the Belated Acquisition by the Bibliotheque nationale in 1945 of over 1,500 works which Cromer’s widow kept with her in France. Amazingly, M Thibaud of Ader auction house appraised works by Édouard-Denis Baldus, Adrien Tournachon and Gustave Le Gray as nearly worthless in comparison to the Felix Nadars, Étienne Carjats, and André Adolphe-Eugène Disdéris. The drama of the collection’s separation, expertly researched by Aubenas, is rounded out by the final essay, in which Jacob W. Lewis intersects Cromer’s collecting practices with Walter Benjamin’s own readings of photography’s histories. In 1931, the same year Cromer approached the French government about acquiring his collection for the nation, Benjamin wrote in the journal Die Literarische Welt, “It is the deepest enchantment of the collector to enclose the particular item within a magic circle, where, as a last shudder runs through it (the shudder of being acquired), it turns to stone…Collecting is a form of practical memory, and of all the profane manifestations of ‘nearness’ it is the most binding.” In thumbing through the images and objects which enchanted Cromer, and reflecting on more than a century of work around his collection, the magic circle extends to an international journey of all shapes and sizes.

The Cromer Collection of Nineteenth-Century French Photography, published May 2022 by Yale University Press. Contributions by Sylvie Aubenas, Eleonore Challine, Ellen Handy, Jacob Lewis, Anne de Mondenard and Heather A. Shannon. Imprint: George Eastman Museum, 328 Pages, 9.37 x 11.50 in, 272 color illus.