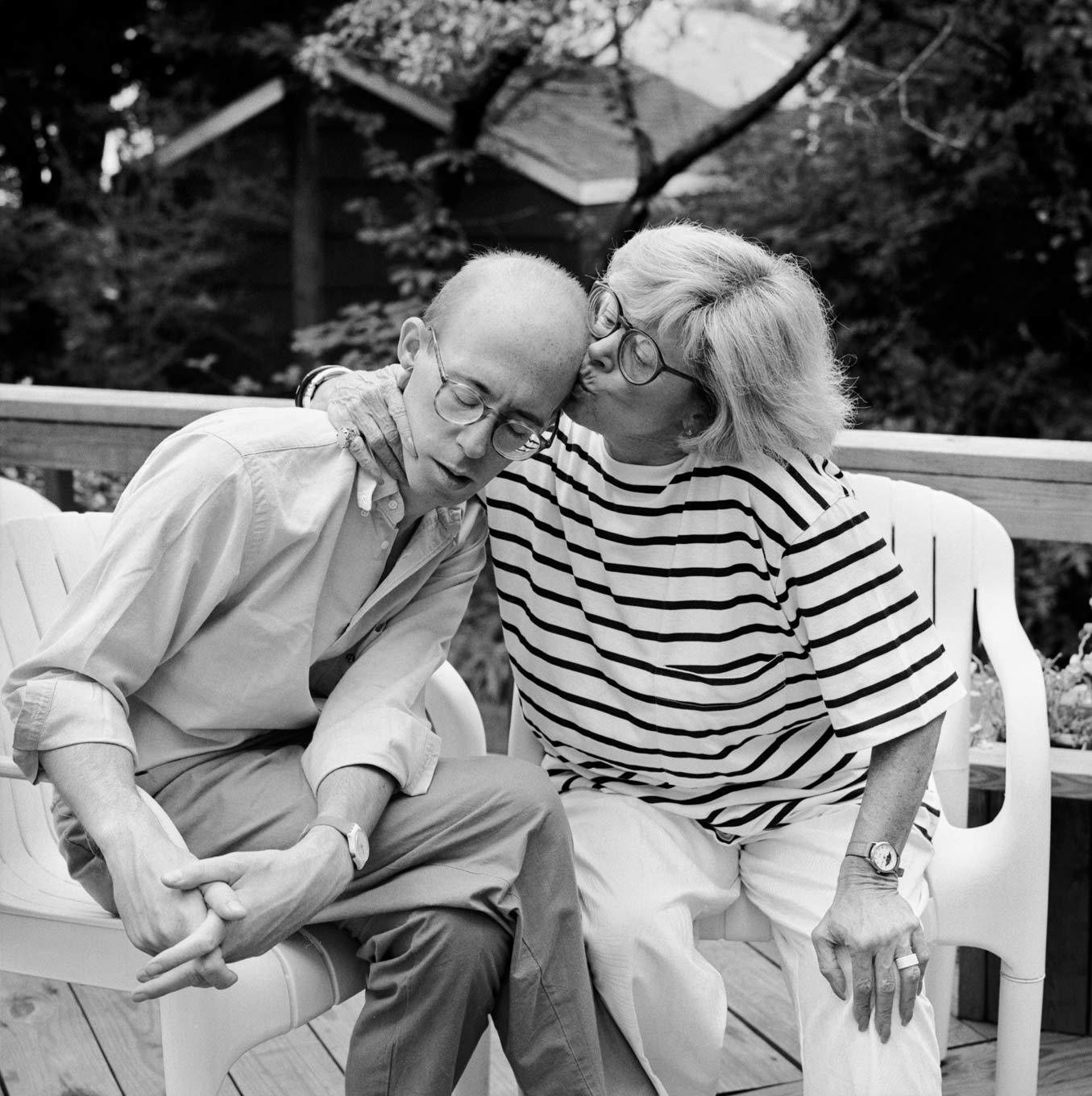

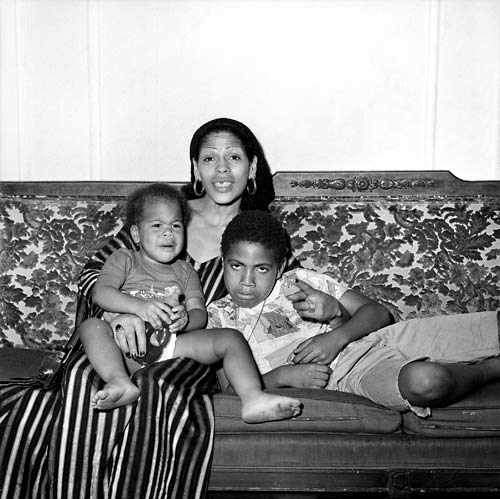

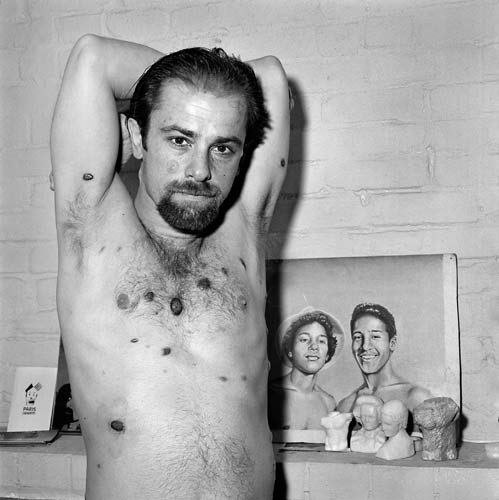

Looking at the images in Rosalind Fox Solomon’s project Portraits in the Time of AIDS 1987 – 1988, I can’t but reflect that while the images were taken not so long ago, it does seem that way. US leaders remained largely silent and unresponsive to the health emergency. Ronald Reagan didn’t even mention AIDS publicly until September 1985, by which time it was an epidemic. In the UK, the government’s first information film didn’t mention the word AIDS. It showed images of an iceberg, the voiceover, provided by actor John Heard, stating, “there is now a deadly virus.” While The New York Times reported on a “mysterious illness” in 1981, it would take almost two years for it to put AIDS on its front cover. In other sections of the press, it was referred to as “the gay plague”, and sometimes worse.

Portraits in the Time of AIDS was first exhibited in 1988. Galerie Julian Sander, Cologne, is restaging a subset of it at this year’s edition of Paris Photo. I posed a few questions to him before the fair.

As of Autumn 2022, your gallery has the exclusive European representation of Rosalind Fox Solomon. How did it come about?

– I have known Rosalind for most of my life. She introduced herself to my father Gerd in 1977 on the recommendation of Lisette Model. Earlier this year Rosalind reached out to me and asked if I would be interested in representing her work in Europe. It was a question that both honoured me and scared me. I have a very deep respect for Rosalind’s work and needed to be sure that I could do the quality of depth of her work justice. After long consideration I agreed.

You are showing Portraits in the Time of AIDS 1987 – 1988. Why do you feel it’s important to show it at this particular time?

–I have spoken before about Rosalind’s fearlessness. This body of work represents one of the most powerful examples of this. The AIDS epidemic is the first I can remember. It was weaponized as a moral cudgel to ostracized people whose love for one another was not in line with the prevalent Judeo-Christian standard. AIDS was, and still is, a deadly disease. Similar in a curious way to what Covid-19 was when the pandemic started. The people then were all isolated, as were we all over the last 2 years. The difference is that AIDS “only” affected a small percentage of humankind whereas Covid hit everyone. I am showing this body of work now because I feel that we, as a species, may now better be able to understand what it was like for the people who contracted HIV and fell ill with AIDS.

The project also speaks to Rosalind’s understanding of humanity and personal connection. The portraits are extraordinary.

At the time, much of the first information, advice, and help came from grassroots organizations. The arts and creative sectors were very active, be it Keith Haring or the creation of the NAMS Memorial Quilt. Was it the silence and passivity of officialdom that led Rosalind Fox Solomon to do the project?

– Rosalind has been in NYC for a very long time. The AIDS epidemic rocked the art scene as much as any other. I have colleagues who lost people. I imagine the closeness of the art world, especially the photography world at that time played a major role.

The project was first shown at New York University’s Grey Art Gallery 1988. It sparked a lot of debate concerning the rights and wrongs, in the climate of the time, of showing AIDS sufferers, visibly ill, in some cases at the very end in hospitals, while society at large was panicked by the epidemic. The project was also criticized for being a fine art project and not a straight documentary project, which seems to underline that it was also a different time in terms of interpreting photographs, with strict divisions between genres.

– It came as no surprise that the USA was in an uproar about anything that challenges the general consensus. It is a country which has grown strong by way of group strength. The fact that the term “The American way of life” is even a thing is testament to this fact. Unfortunately, group cognition and individual observation do not really go together so well. Now, more than ever, we tend to (pre) judge people by group identity. It is a curse of our time. As for the idea of straight documentary work vs art, what the fuck is that supposed to mean? The artist does not decide if what they make is art, we the viewers and buyers do that. Andy Warhol enlarged packages of Brillo to bring attention to the artistic value of the graphic designer who designed them. They became art because Warhol made them big and we bought and resold them. Life is complicated. Art is complicated. The inability to see a thing as fulfilling more than one function is an indication of the viewers lack of capacity, not the objects.

What are your hopes for the project? That it will be bought by an institution?

– This project is so very important because the use of the photographic image, which we understand to be true, is used to create a degree of inner challenge, a cognitive dissonance. The way each of us see these portraits and judge the sitter is a direct reflection of how we see and value each other. It challenges the myth that we will live forever. I think an institution could be a good home for this body of work, as long as it is in Europe. I would also welcome a pharmaceutical company’s collection, like Pfizer for example. As much as we love to hate on big medicine, there are people in medical research who are doing extraordinary work. The Covid vaccines are a modern-day miracle. Maybe one of these companies is interested in a collection of work that reflects more than the amount of money they have and shows some of the people for which the work they do is intended.