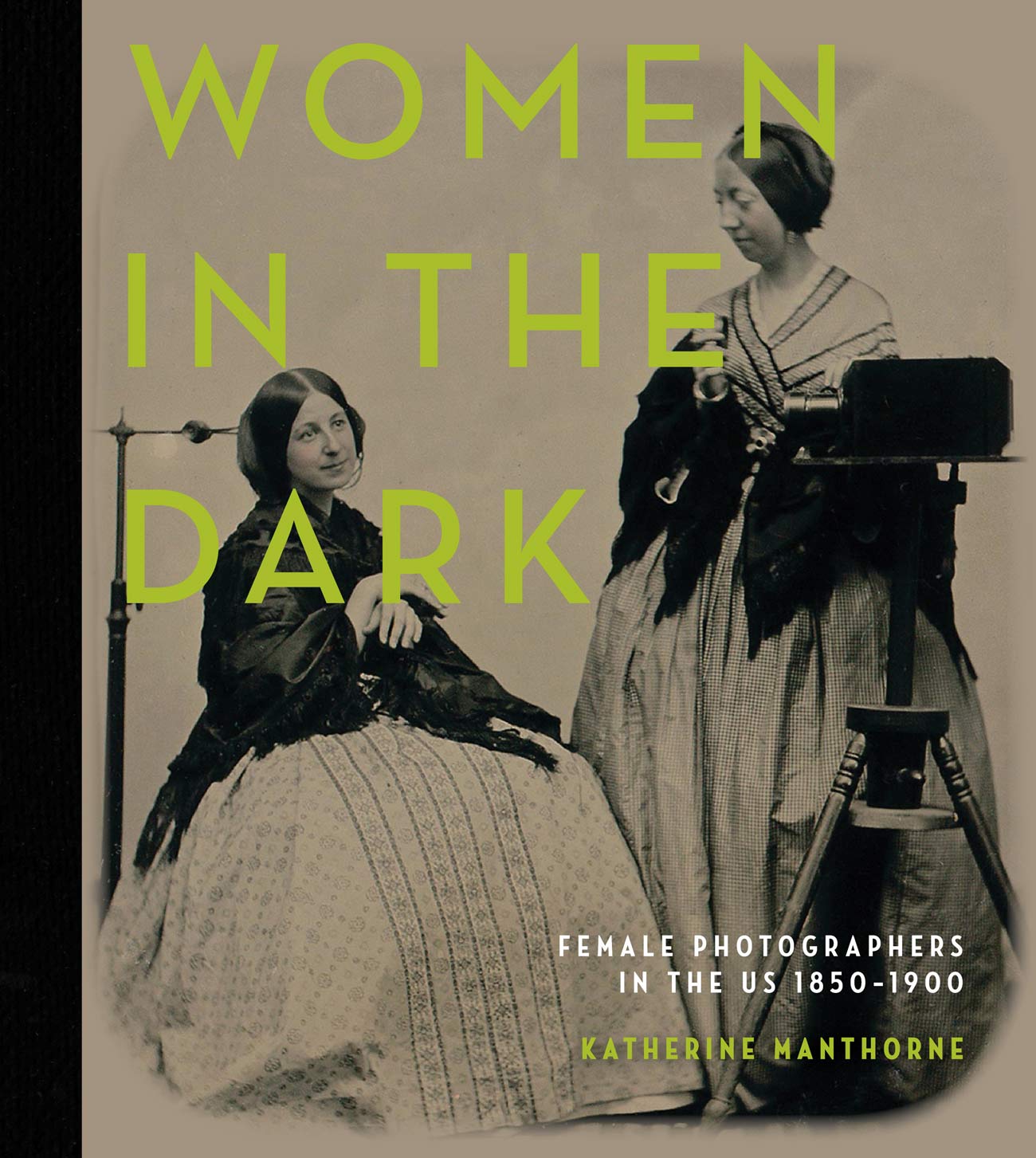

On April 22, 1890, citizens of the central Kansas town of McPherson were greeted with a directive in the local paper: “Expression is the key to character. Think of this then have Mrs. Vreeland Whitlock take your picture.” Rosa Vreeland-Whitlock’s penchant for inventive advertisements led to a successful 30-year career as a studio photographer – and earned her a place in Katherine Manthorne’s new book, Women in the Dark: Female Photographers in the US, 1850–1900.

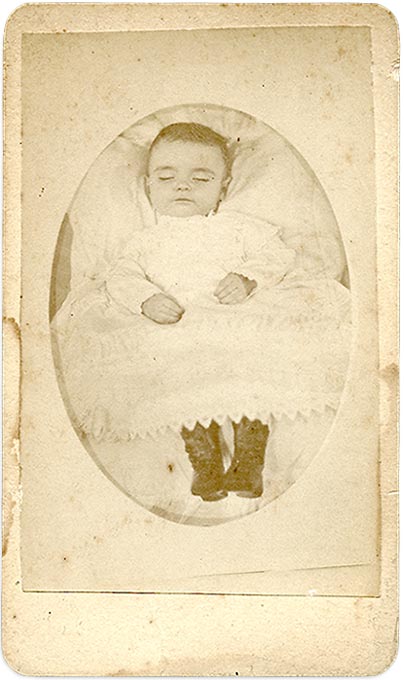

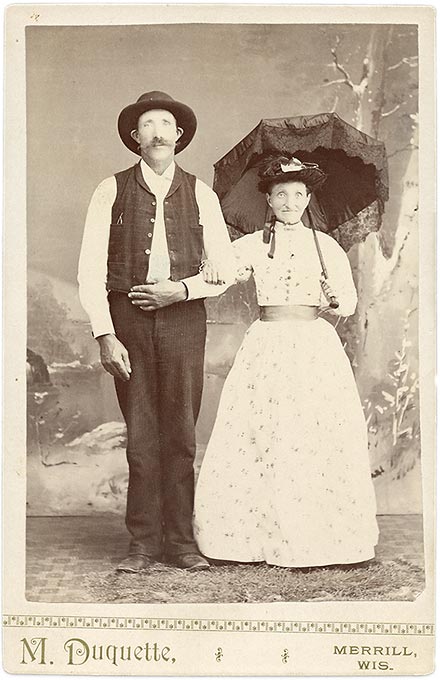

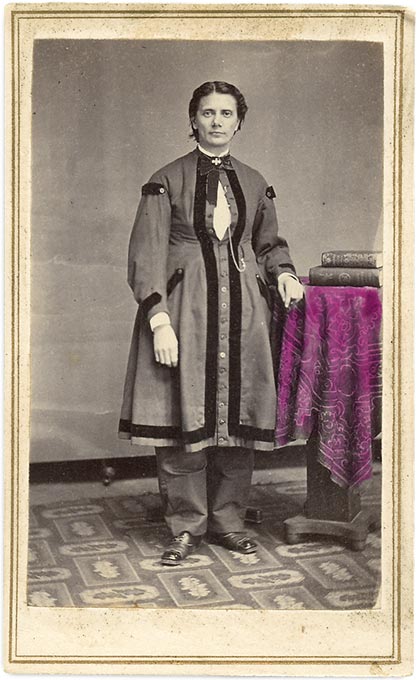

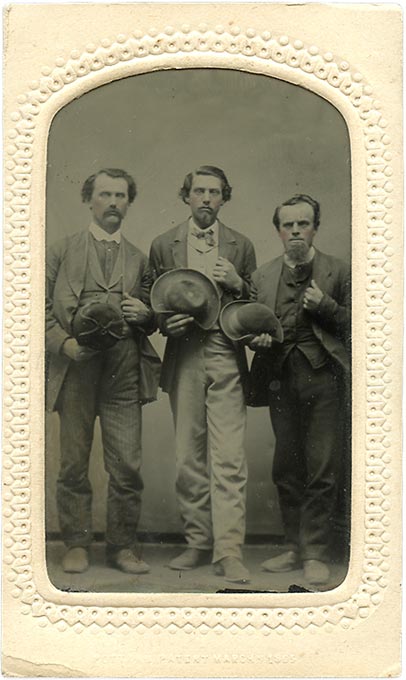

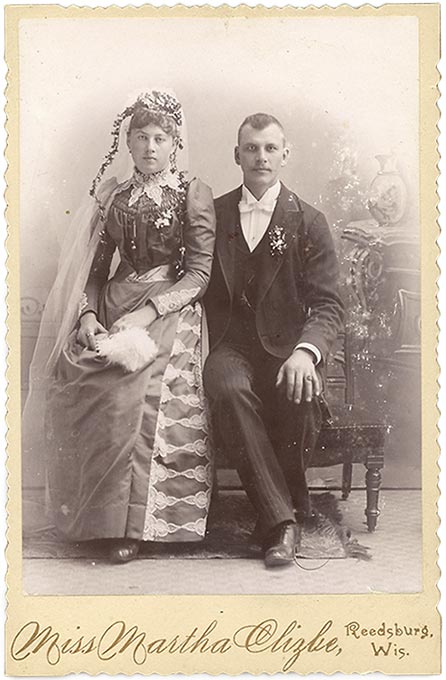

Embedded in the title of the book, of course, is an unmistakable double meaning: women not only created images in the darkness of their darkrooms, they have simultaneously (and, frustratingly) been largely left out of America’s early photo-historical narrative. Over the course of six detailed chapters, Manthorne, an art history professor at the Graduate Center, City University of New York, introduces the overlooked studio and commercial photography practices of American women in the latter half of the 19th century. Her research is impressive in its breadth of sources, and has been translated into a series of lively ‘mini-chapters’: case studies of individual female photographers within the book’s broader themes. Following a loose chronology, Women in the Dark examines the lives and businesses of the many women taking pre-battle portraits of soldiers off to fight in the Civil War, running roaring tintype trades, making harmonious wedding portraits, capitalising on the popularity of post-mortem photographic keepsakes, and more.

In her introduction, Manthorne quickly points out the ways in which her pursuit of re-inserting female photographers into America’s visual history “presents the opposite challenge to the majority of women in the visual arts.” Painters may only leave behind a few examples of work, and traces of a reputation to build upon, but 19th century studio photographers’ names can appear on countless cartes-de-visite, or cabinet cards – each one material evidence of a signature and commercial identity. Often, there is little else on which to assemble a narrative around their lives and livelihoods.

Where information on the photographers may be lacking, Manthorne dissects the visual evidence available – what is the sitter wearing? What rank was this soldier from the Union Army, and could he have embellished his uniform in the confines of the studio? How has the photograph aged, and what can it tell us about the photographer’s technical mastery? Asking these questions when assessing a photograph are routine, however Manthorne’s many case studies dissect the ways in which female photographers’ social experiences inform not only the photographs they make but how they made them – each one unique to their particular location, family makeup, wealth, and personality.

One of the most interesting threads to run through each of these chapters is evidence of commercial marketing employed by women across the country, such as the encouraging words of Vreeland-Whitlock, who Manthorne deems a ‘Public-Relations Wizard’. Advertisements, reviews, or ‘For Sale’ announcements of studio space or equipment once business has dried up – each of these provide clues and offer insight into how women highlighted their gender while securing their commercial reputations. ‘Best Light in Town’, announced Candace Reed in the early 1860s, after she sold her late husband’s daguerreotype stand in Quincy, Illinois and took up the wet-plate collodion process. She followed it up with a canny notice: “Patronize the widow, and thus give bread and education to orphans.” Others are simply entertaining. An 1890 ad for a Chicago studio, in which Virginia Hartley Stiles was a partner, asked this pointed question: “IS MARRIAGE A FAILURE? You would not think so could you see the lovely brides and happy bridegrooms that throng Hartley’s Studios, eager to secure a Crayon or Cabinet portrait of their wedded bliss.”

Manthorne builds on earlier work primarily undertaken by private collectors (notably Peter E. Palmquist and Julia Draper, and their collections now held at Yale University), and Women in the Dark is a welcome and necessary addition to 19th century photography scholarship. This history, however, is still overwhelmingly white. The only photograph of a Black American to appear in the book is a portrait of Sojourner Truth, which opens the chapter entitled ‘The New Woman and Women’s Rights’; we are left wanting more critical insight into the work of Sarah Short Addis, who made images of indigenous men and women in Chihuahua, Mexico in the late 1800s. Women in the Dark has skillfully reclaimed space for women in the history of American photography, but we can also take this new book as inspiration – to open up further narratives that have been consigned to historical darkness. As Manthorne has illustrated here, there is still so much to discover.

Women in the Dark: Female Photographers in the US, 1850–1900 (2019) by Katherine Manthorne is published by Schiffer and can be purchased here.