Up to now very little was known about American-born stereo daguerreotypist Warren Thompson and the information we had about him was very scant, so much so that nobody knew when and where he was born or what happened to him after the early 1860s. This article aims at providing never-published-before answers to some aspects of the life of this remarkable photographer, who is mainly known through a fairly small quantity of surviving stereo daguerreotypes which include some staged self-portraits. There is still a lot to be found about this pioneer of stereo photography, especially regarding his private life, but the new facts revealed here may help someone devote a more thorough study, even a book maybe, to this fascinating figure.

Warren Thompson was born Elijah Warren Thompson, at Walpole, Norfolk, Massachusetts, on 17 December 1814, the first child of Elijah Thompson Jr. (25 March 1790-7 December 1861) and his wife Roxanna Colburn (10 December 1794-10 February 1884), a twenty-year old young woman from Dedham, Massachusetts. There is little doubt Elijah Warren was conceived out of wedlock and that his mother was already pregnant when she married, on 31 July 1814,1Sources differ as to the actual date of the wedding, one mentioning 30 July 1813 just over four and a half months before his birth. Being the first born, the child was naturally named after his father, who had himself been named after his own father, another Elijah Thompson (1762-1846). However, his middle name, Warren, came from his mother’s side. She had an elder brother named Warren Colburn who was born at Dedham, Massachusetts, on 1 March 1793, and died at Lowell, also in Massachusetts, on 13 September 1833. Warren Colburn was the author of a fairly famous book, which became known as Colburn’s First Lessons: Intellectual Arithmetic, upon the inductive method of instruction, and was first published in 1821 under the title First Lessons in Arithmetic, on the plan of Pestlalozzi. It was re-issued several times and was still being printed eighty years after its author’s death. Warren Colburn married one Cordelia Temperance Horton (1799-1870) on 29 June 1823 and had six children over the short ten years of their married life.

We do not know much about Elijah Warren Thompson’s childhood, apart from the fact that he had at least one younger brother, Charles Edmund, born in 1816, and two sisters, Sarah Maria and Mary Irene, respectively born in 1818 and 1820.

By the 1840s, Elijah Warren Thompson had moved to Philadelphia, where he was already working as a photographer and gained some fame by improving an electroplating method for colouring daguerreotypes which had been patented in 1842 by daguerreotypist Daniel Davis Jr. (1813-1887).

If we are to believe an article published in the American Journal of Photography in October 18922The paragraphs about Thompson are extracted from the fifth in a series of articles devoted to the history of photography and published under the title Early Daguerreotype Days. An Historical Retrospect. By Julius F. Sachse. by its editor, Julius Friedrich Sachse (1842-1919), Warren Thompson moved to Paris in 1845 and although the daguerreotype was a French invention, stunned the Parisians with the size and quality of his images:

Strange at it may appear, photographic portraiture was not a success in Paris until the advent of an American in 1845, viz.: Warren Thompson, of New York. Thompson came to Paris without being able to speak a single word of French. He merely had a letter of introduction from the Russian consul in New York to his vice-consul Iwanow, in Paris. The latter turned the American over to Levitzky, who received him cavalierly, supposing him to be a mere amateur. He was soon disabused when Thompson produced his specimens. They proved far better than anything which had so far been seen in Europe. Neither Paris, Vienna, nor Rome could produce such results. Levitzky, then one of the leading daguerreotype artists in Paris, writes: “They were not daguerreotypes, they were works of art.” [quoted in Photographische Zeitung, Volume XVI, p. 221] Here was strength, relief, artistic lighting, softness of shadows, with a wealth of half tones. All specimens were on half-plates. This itself was a revelation, as thus far in Paris nothing larger than quarter plates had been used.

Thompson at once opened a studio in a large building in Boulevard Poissonier3Actually 14, Boulevard Poissonnière, in what is now the 9th arrondissement of Paris., Maison du pont de fer. The studio contained two stories, with three large rooms, having three windows. So superior were Thompson’s results, that, notwithstanding the competition of native operators, his sitters averaged from thirty to forty per day.4American Journal of Photography, October 1892, pp. 451-2.

Sachse’s article is the only source we have about Thompson’s early years in Paris but he is, unfortunately, not a very reliable researcher, often getting mixed up in his dates. At the beginning of the section devoted to Warren Thompson, for instance, he claims that Claudet and Lerebours took a portrait of King Louis Philippe in 1840 when we know from sources of the time that the event actually took place three years later. Mentioning the same Claudet, Sachse states that he opened a studio in London in 1840 when it is established it did not happen until 1841. It is, however, a fact that Warren Thompson’s first studio was established at 14 Boulevard Poissonnière, although his name does not appear in the trade register until 1849, the same year he won a medal at the exhibition of industrial products held in Paris from 1 June to 30 July.

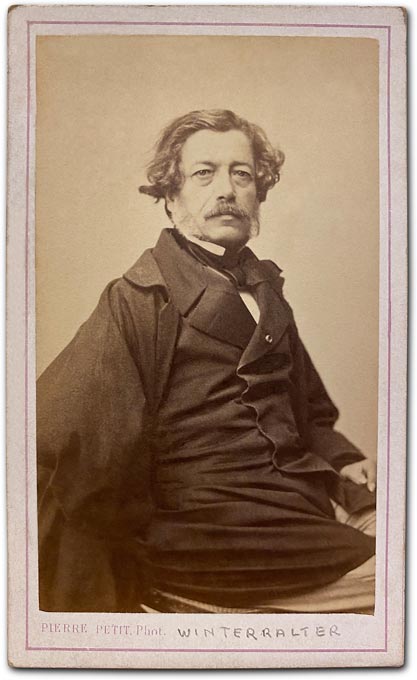

By the end of 1850 Warren Thompson had moved to 24, rue Basse du Rempart5The rue Basse-du-rempart, which disappeared in 1858, was also in the 9th arrondissement., where he tried to set up a society for the production of daguerreotypes with one Arsène David, merchant. Due to some documents they failed to fill in the society could not be legally created. In the building where he now operated lived one Béral, a manufacturer of chemicals, and, more interestingly for the rest of Thompson’s career, an artist who was to become one of the most popular painters of crowned heads in Europe, Franz Xaver Winterhalter (1805-1873). The portrait photographer and the portrait painter must have met on different occasions during the two to three years they lived in the same house and, although their relationship deserves to be explored in more depth, they probably learnt a lot from each other.

In 1851 Thompson took part in the London Great Exhibition where he was awarded a bronze medals for his daguerreotype portraits. On this occasion he was also mentioned for the first time in the photographic magazine La Lumière, in its 2 March issue:

M. WARREN THOMPSON, 14, boulevard Poissonnière, Paris.

The size of the portraits exhibited by M. Warren Thompson, especially his full-length self-portrait and the scene with drinkers he staged in his studio, offers the pleasing results of an overcome difficulty. One would probably wish to see less distortion in the features, as well as a brighter and sharper way of lighting the sitters; but such as they are his portraits surpass in size, luminosity and general effect anything that had been produced so far. Let us add that as far as his smaller portraits are concerned M. Thompson operates with rare speed and mastery, has numerous patrons and fulfills all the conditions which are most appreciated by the jury. He has improved the processes, made them faster and more reliable and his turnover in this particular branch of industry can be deeemed considerable.

The jury awards him a BRONZE MEDAL.6La Lumière, 2 March 1851, p. 14. M. WARREN THOMPSON, boulevard Poissonnière, 14 bis, à Paris. La dimension des portraits exposés par M. Warren Thompson, surtout son propre portrait en pied et la scène des buveurs composée par lui, offre les résultats heureux d’une difficulté vaincue. On désirerait, sans doute, trouver dans les traits moins de déformation, et dans la manière d’éclairer le modèle une lumière plus franche, un effet mieux accusé; mais, tels qu’ils sont, ils surpassent de beaucoup, en grandeur, en clarté et en réussite générale, ce qu’on avait produit jusqu’à ce jour. Ajoutons que M. Thompson, dans ses portraits de dimensions ordinaires, procède avec une sûreté et une rapidité rares, qu’il dessert une clientèle nombreuse, et répond, en un mot, aux conditions les plus appréciés par le jury. Il a perfectionné les procédés, il les a rendus plus faciles, plus sûrs; il a atteint enfin un chiffre d’affaires qu’on peut appeler considérable dans cette industrie. Le jury lui décerne une MÉDAILLE DE BRONZE.

The Great Exhibition of 1851 was also where the stereoscope – invented as early as 1832 by Charles Wheatstone, but not commercially available in a portable format until 1850 – was officially launched and started becoming known. By the end of 1852 Warren Thompson, who had now moved to 22, rue de Choiseul, in the 9th arrondissement, had not only started taking portraits for the stereoscope and advertising the fact in the 1853 trade directory, but had also patented a new form of stereoscope, as could be read in the Industrial review at the end of the said trade directory:

Thompson (W.), dagerreotypy, photography (medals at the exhibitions), portraits and groups in large formats, reproductions of paintings, engravings, artefacts, STEREOSCOPIC (in relief) PORTRAITS AND GROUPS, stereoscopic images on plate, glass and paper, plates for the daguerreotype, chemicals, etc., lenses in all sizes, rectified and guaranteed by W. T. rue de Choiseul, 22, at the corner of the Boulevard des Italiens. (See the Industrial Review).

INDUSTRIAL REVIEW

W. THOMPSON, rue de Choiseul, 22, Maison du Cercle des Arts.

We specially recommend the salons, Daguerreotype and Photographic studio of M. W. Thompson, this eminent American artist who, for the past six years has been giving such a great impulsion to the Heliographic art, patented inventor of a new stereoscope which gives the wonderful illusion of natural relief to photographic views and portraits.

Portraits on plate, glass, paper and fabric; Stereoscopic portraits and views, lenses, cameras and chemicals. Medals at the exhibitions. Rue de Choiseul, 227Trade register for 1853. Thompson (W.), daguerréotypie, photographie (médailles aux expositions), portraits et groupes de grandes dimensions, reproductions de tableaux, gravures et objets d’art, PORTRAITS ET GROUPES STÉRÉOSCOPIQUES ou en relief, images stéréoscopiques sur plaques, sur verre et sur papier, plaques, produits chimiques, etc., objectifs de toutes grandeurs rectifiés et garantis par W. T., rue de Choiseul, 22, au coin du boul. des Italiens. (Voir la Revue Industrielle). REVUE INDUSTRIELLE. W. THOMPSON, rue de Choiseul, 22, Maison du Cercle des Arts. Nous recommandons d’une manière toute spéciale les Salons et les Ateliers de Daguerréotypie et Photographie de la Maison W. THOMPSON, de cet éminent Artiste américain qui, depuis six ans, a donné en France une si grande impulsion à l’Art Héliographique, inventeur breveté d’un nouveau Stéréoscope, instrument qui a pour effet merveilleux de donner la sensation du relief naturel aux Portraits et aux Images Photographiques. Portraits sur plaque, sur verre, sur papier et sur étoffe; Portraits et Images Stéréoscopiques. Objectifs, Instruments et Produits chimiques. Médailles aux Expositions. Rue de Choiseul, 22

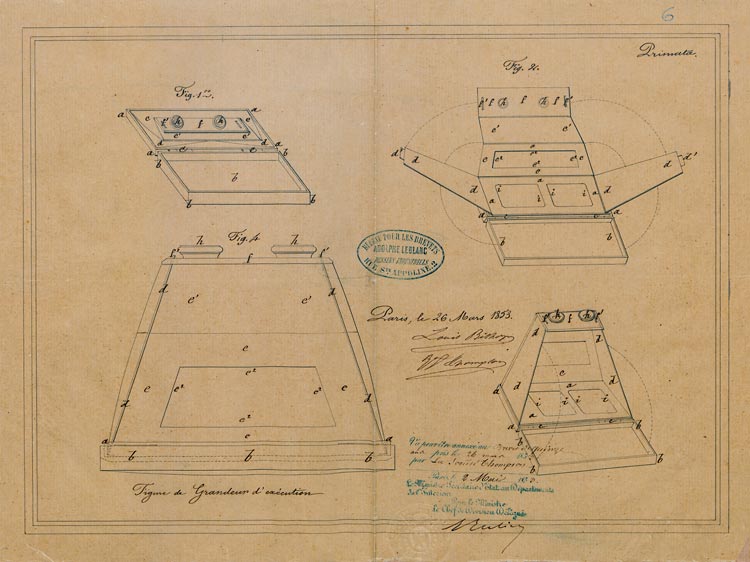

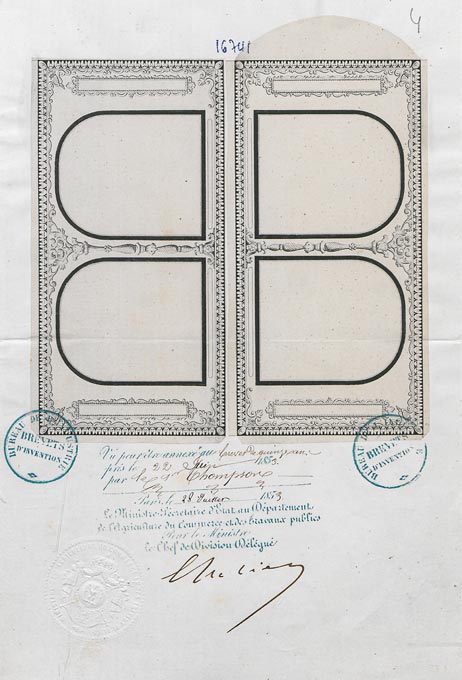

Thompson actually filed two patents in 1853. The first one (No. 15984, 26 March 1853) was for a folding stereoscope, the second one (No. 16741, 22 June 1853) for protective sleeves in copper, zinc, paper, or gutta percha, for daguerreian images, more particularly stereoscopic ones. Thompson called these sleeves “enveloppes conservatrices” (preserving envelopes) because they could be folded like an envelope, as shown in the accompanying drawing.

The first patent was filed, for Warren Thompson, by Louis Laurent Bishop, a photographer and the managing director of the company Thompson had created under the name W. Thompson. Little is known about Louis Laurent Bishop who was born at Paris on 10 November 1813 to Thomas Victor Bishop and Anne Alexandrine Perrée and died at Nanterre on 24 May 1896. He married one Mathilde Sophie Weston (1832-1887) on 23 June 1857 and had at least two sons, William Eugène, who became a chemist, and Lucien (1874-1936).

Since Thompson did not start taking stereoscopic daguerreotypes prior to his move to 22, rue de Choiseul, Sergei Levitzky’s former studio, all his stereoscopic production bears this address, usually on the front and printed on the inside of the piece of glass that protects the plate.

Thompson’s stereoscopic daguerreotypes have a particular charm of their own. There is no doubt he was a talented photographer and an excellent portraitist. A good case in point is the beautiful portrait of this young girl whose identity, unfortunately, remains a mystery.

Thompson also photographed statuary, stuffed animals and groups, an example of which is given here. It shows a mother giving her two children a geography lesson. It is very similar in spirit to a more famous image by Claudet entitled “the geography lesson”.

In 1855 Thompson took part in the International Exhibition that was held in Paris and featured in the book Henri Boudin devoted to the analysis of some of the products on display:

THOMPSON (Warren), rue de Choiseul, 22, à Paris.

Photographic portaits from the smallest dimensions to life size, remarkable likenesses, tinted or untinted.

Ordinary daguerreotypes, also in all sizes, of never-equalled-before perfection and finish.

Portraits for the stereoscope, tinted, providing a wonderful and astonishing likeness.

Stereoscopic views and stereoscopes of different designs and for various purposes.

We especially draw the attention of the public and amateurs to a new system of stereoscope, invented by M. Warren Thompson, which was admitted to the exhibition and can be seen inside the Palais de l’Industrie and at the inventor’s.8Boudin Henri, Le palais de l’industrie universelle: ouvrage descriptif ou analytique des produits les plus remarquables de l’exposition de 1855, p. 161. THOMPSON (Warren), rue de Choiseul, 22, à Paris. Portraits photographiques depuis la plus petite dimension jusqu’à celle de grandeur naturelle, de la plus grande ressemblance, coloriés ou non coloriés.Daguerréotypes ordinaires, aussi de toutes dimensions, d’une perfection et d’un fini qu’on n’a pas encore atteints.Portraits au stéréoscope, coloriés, d’une ressemblance merveilleuse et vraiment surprenante. Vues et stéréoscopes de différentes constructions et pour divers usages. Nous appelons surtout l’attention du public et des amateurs sur un nouveau système de stéréoscope, inventé par M. Warren Thompson, qui a été admis à l’Exposition, et que l’on peut voir au Palais de l’Industrie et chez l’inventeur.

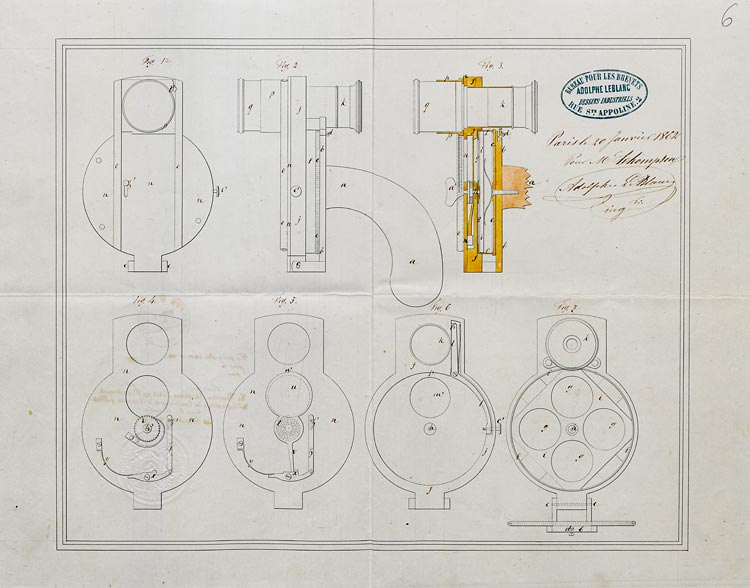

Thompson’s work was rewarded with a first class medal which was mentioned in subsequent entries in the trade directories. Despite his success in the photographic field Thompson seems to have drifted away from photography after 1858. That year he filed a patent (No. 36431) for improvements in the electric telegraph. Two years later, he disappeared from the trade directory, and Sergei Levitzky, who had been operating a studio in his native Russia, took over the studio that had been formerly his at 22, rue de Choiseul. In 1861 Thompson filed another patent (No. 51165), this time for a printing telegraph, and the following January, he went briefly back to photography with a new patent (No. 52713) for a photographic revolver – a copy of which was recently sold at an auction – which allowed the user to take four successive round images on a square glass plate.

After this we lose trace of him, at least until 1871, when the British census reveals that he was then living at 15 Vincent Street, Finsbury, London. He is listed as a 56 year old artist from the United States of America, a visitor at the house of one James Tunwell, a carpenter and a 62 year old widower, from Bath. Although Thompson is described as being married, his wife is not listed with him and, to this day, I have not been able to find any trace of her name or of their marriage and I do not know whether they tied the knot in France or in Britain, nor when exactly Thompson moved from Paris to the London area. Did he leave just after 1862 or did he wait until around 1870 when it was clear there would be a war in France ?

The 1881 census finds him at 16, Englefield Road, Hackney, London, a widower and a lodger at the house of one Ann Masters, 60, a waistcoat maker who was living with her twenty-year-old niece. What happened to his wife is still a mystery but the enumerator describes Thompson as an artist (a painter) from Walpole, America.

Things appear to have improved for Thompson as the 1891 census reveals he is now the head of his household, at 24 Grange Park, Croydon, where he is described as being a portrait painter and a sculptor from Massachusetts. We also learn that he has apparently married again. His 56-year-old wife is called Elizabeth J. (Jane ?) and is from a market town in Devon called Honiton. Once again, however, I have not been able to find any trace of this second marriage.

The Thompsons must have liked it in Croydon since they were still there in January 1901 when Warren Thompson, aged 86, breathed his last and was buried. Thompson only saw the first two weeks of the twentieth century and since he died nearly at the same time as Queen Victorian he can definitely be called a Victorian photographer.

As I said earlier, there are still lots of mysteries to solve and lots of grey areas in the life of Warren Thompson (his marriages, his career as a painter and a sculptor, his relationship with Winterhalter, the missing years of his life, among other things) but my hope is that this article will inspire someone to pick up the trail where I left it and to write something more substantial and more thorough about this very interesting photographer and stereo daguerreotypist, Elijah Warren Thompson (1814-1901). He was born and educated in the States, acquired fame in France and spent the last thirty years of his life in Britain, a true citizen of the world.