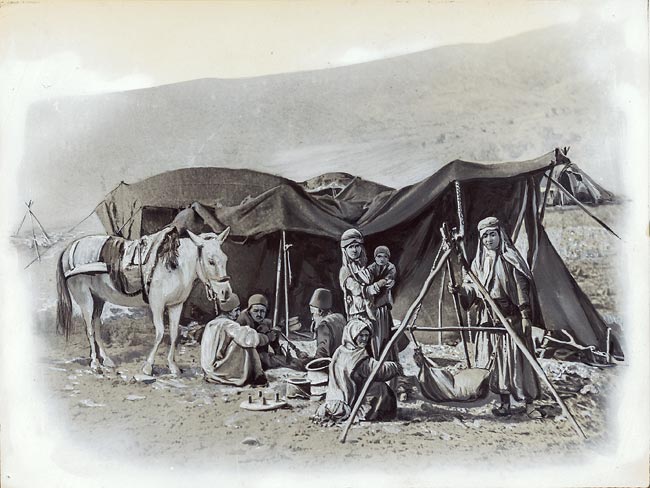

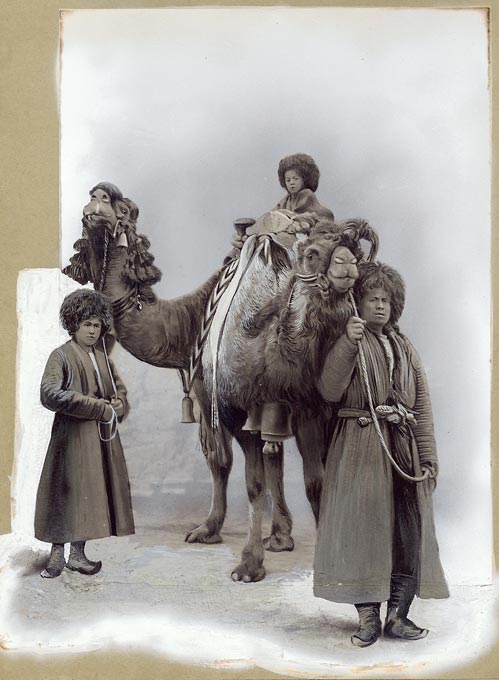

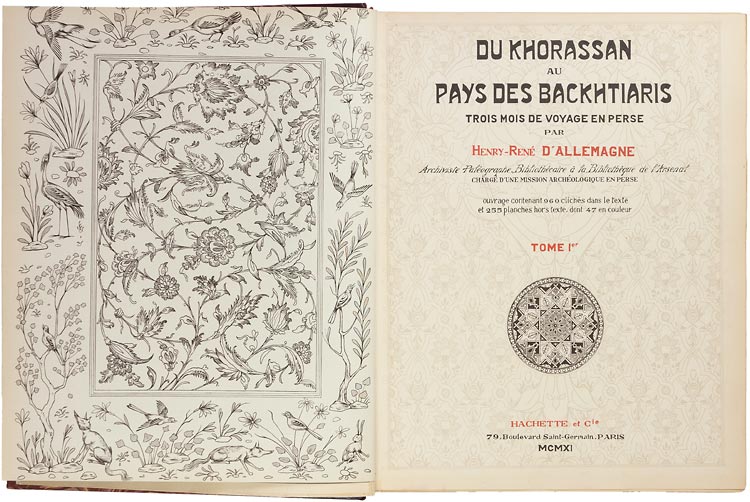

It’s a fascinating collection. An exceptional archive, regrouping a set of 403 original photographs, printed on albumen paper from glass negatives, or in some cases on gelatin silver paper, and mostly taken by Henry-René d’Allemagne during his various archaeological, ethnographic and artistic expeditions in Persia between 1898 and 1907. They were used as the main iconography for his mammoth book entitled Du Khorassan au Pays des Backhtiaris : trois mois de voyage en Perse (From Khorassan to the Land of Backhtiari: three months of travel in Persia), Paris, Hachette, 1911, 4 vols.

Of those 403 photographs, 386 were used to illustrate the book – six of them being printed twice – and 17 had never been published before.

The majority of these photographs were taken by Henry-René d’Allemagne, while some were taken by Jacques Bizot (33), General Bazirguian (7), Paul Nadar (4) and Dr Jean-Baptiste Feuvrier (2). Our set includes nine of the 33 photographs by Jacques Bizot and one photograph (of the two) by Dr Feuvrier.

These original photographs were mounted in an unbound album, each image accompanied by a written caption, carefully printed. However, some variations may appear. Some prints come with handwritten notes in the margins, probably added by Henry-René d’Allemagne himself.

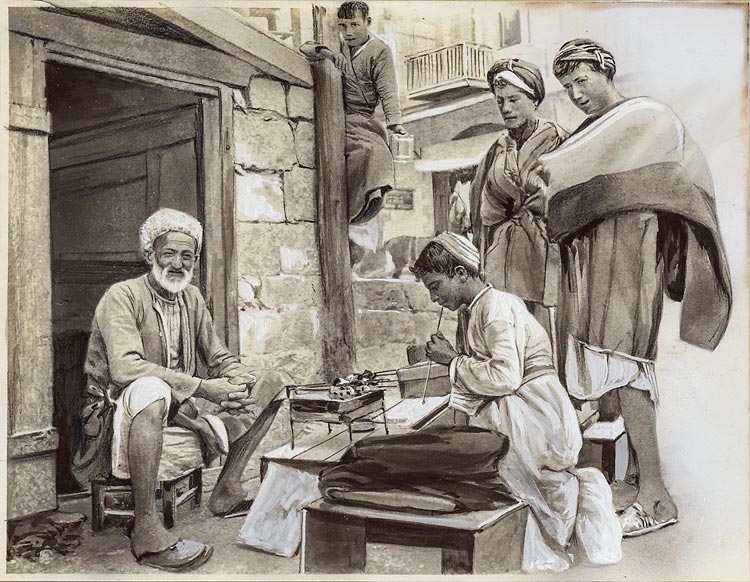

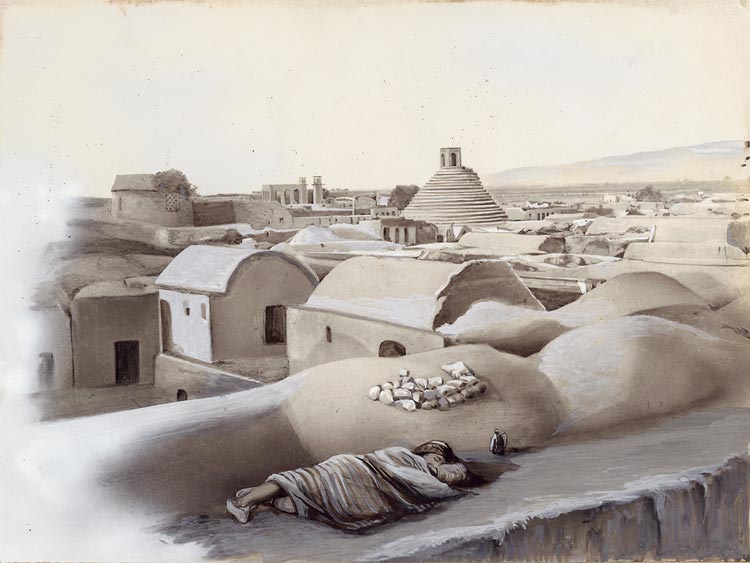

Many photographs from this ensemble were enhanced with gouache and potassium ferrocyanide to obtain the best quality possible during the photo-engraving process while printing the book.

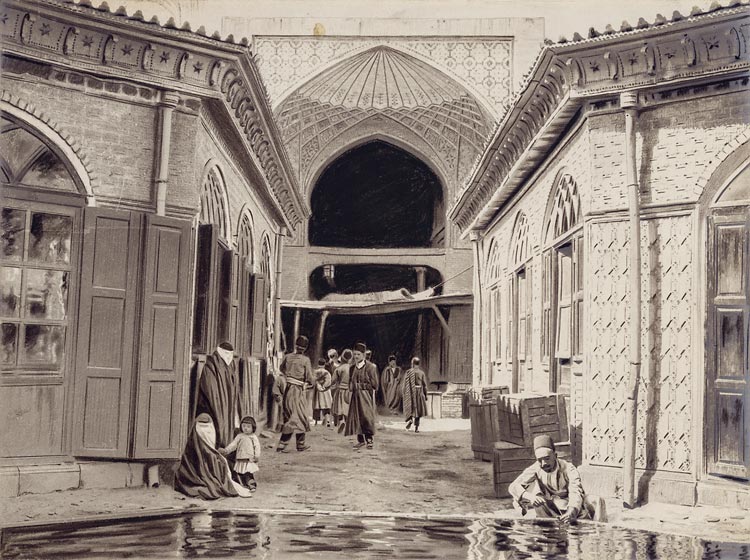

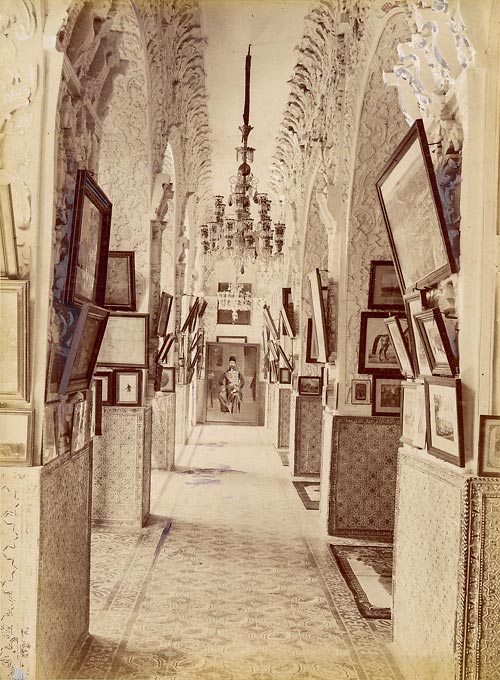

In addition to numerous genre scenes, there also several images depicting famous people, including the Shah of Persia, along with disciples of Nestorianism, Dervishes, children, women, families, and the author himself with his travelling companion, soon-to-be Dr Vinchon, posing on several occasions for posterity (I, p.224 out-of-text; III, pp.140, 188 and 198; IV, pp.155 and 213). The photographer immortalised different ethnic groups: Jews, Kurds, Persians, Armenians, Ghebres, Talishis from Mazandaran Province, Turkmens, Bakhtiari, Cossacks and Russians. Also of note are some splendid views of landscapes, various palaces, mosques, numerous bazaars, cemeteries, schools, a scholar’s library, interiors of an antique shop, ruins, etc.

The photographs present multiple picturesque scenes of daily life and various occupations: grocers, bakers, dentists, barbers, dry cleaners, carpenters, potters, bankers, peddlers, singers and musicians, street merchants selling poultry or syrup, craftsmen, cooks, wood merchants, painters, ceramic painters, farm workers, customs officers, falconers, “Jewish antiquities dealers in search of a good deal”, as well as numerous activities like the production of bread, butter, clothing, carpets, felt, bricks and opium, laundry cleaning, house building, weddings, dances and feasts, traditional costumes, wrestling, religious parades, prayers, ablutions, harems, the transportation of corpses, burials, the cleaning of turquoise stones after mining, tiger hunting, etc. We can also observe scenes of farmers working the fields, harvesting, seed grinding, cotton and tea picking, along with carding, wool spinning and mowing, the throat-slitting of goats and the immolation of sheep and other animals (don- keys, camels, horses, oxen, goats, sheep, rams and dogs).

Eminent archivist and palaeontologist, librarian, historian, image collector, art historian, amateur photographer, Orientalist and traveller Henry-Réné d’Allemagne (1863–1950) is an encyclopeadic reference, a true representative of erudition and the enlightened art of collecting in the second half of the 19th century and the first half of the 20th.

It was with the opening of the Trans-Caspian railway, which was under construction between 1879 and 1895, that Henry-René d’Allemagne was first inspired to visit Persia. In 1890 he planned a trip with his friend, engraver Émile Vaucanu, but he soon realised the impossibility of such an enterprise. Vaucanu, nevertheless attracted by the prospect, went on alone and without funds, boarding a boat in Marseille to Batumi, where he started to make a living from drawing. On his way to Tiflis he was assaulted and left for dead, only to be saved in the nick of time by a charitable soul. After this regrettable incident he received help to make his way to Baku, then crossed the Caspian Sea to Ashgabat where he forged a strong friendship with a French engineer working on the construction of the Trans-Caspian railway. Vaucanu continued his journey towards Samarkand, and from there, he went south-west towards the Pamir mountains in order to make sketches of the scenery, which were destined for inclusion in an album of etching designs. Around 275 kilometers from Samarkand, in a location free of Russian authority, he encountered some Turkmen, who murdered him, thinking they were robbing a rich traveller. It was thus in 1898, with the intention of undertaking a personal investigation to solve this crime by himself, that d’Allemagne went for the first time to Samarkand and Bukhara. With the aid of the Russian authorities, he managed to uncover some answers about the odious crime.

D’Allemagne made a second visit to these lands in the summer of 1899, travelling to Khorasan, Meshed, Nishapur, Sabzevar and Guchian. During a visit to the court of Meshed’s Viceroy, and thanks to an automatic lighter gifted to the local authorities, d’Allemagne obtained permission to carry on some excavating and the right to keep any discovered objects. But while photographing views of Guchian’s streets and bazaar, d’Allemagne was arrested and thrown into jail on suspicion of espionage. During this incident the permission that had been granted by Meshed’s Viceroy “mysteriously vanished”. On the verge of winter, d’Allemagne left the country for Russia.

In 1907 and now a veteran traveller in these areas, d’Allemagne was entrusted by the French Ministry of Education with an archeological mission in Persia – to investigate the condition of ancient monuments, a great number of which had deteriorated or been destroyed during the recent wars and the 1907 revolution. Simultaneously d’Allemagne received an invitation from Serdare Assad, military chief of the Backhtiari tribe, to visit his domain. During this journey, between September and November 1907, d’Allemagne decided to enter Persia via Russian Turkestan, sojourning briefly in Meshed, and then went to Tehran afterwards, taking the opportunity to visit Nishapur, Sabzevar, Shahrud and Varamin. From Tehran he made his way to Ispahan, following the main road that goes through Qom and Kashan. He then went to Djounougoun, the Backhtiari’s summer residence and his host’s permanent home. The return trip followed the same itinerary to Tehran, from where he made way to Europe along the road from Qazvin to Recht and Enseli, and then to Baku across the Caspian Sea.

To ensure the successful completion of his journey and the development of his book, d’Allemagne enlisted the help of Hadji Ali Gholi Khan, who arranged for a group of soldiers from his tribe to accompany the French traveller. Khan also took part in the elaboration of the book, writing essential notes on the manners and customs of Persia in general, and of his tribe in particular. Soon-to-be Dr Jean Vinchon, d’Allemagne’s travelling companion,1According to Svetlana Gorshenina, Vinchon was “a relative” of d’Allemagne (in Explorateurs en Asie centrale. Voyageurs et aventuriers de Marco Polo à Ella Maillart. Génève: Olizane, 2003, pp.303 and 305) also played his part during the expedition, consigning to a precious journal or log book his feelings upon observing the imposing Persian landscapes. This book became a “constant guide” for d’Allemagne. Meanwhile, a precious note on miniaturist painters and Persian manuscripts was written by Georges Marteau, engineer of the arts and manufacture.2Henry-René d’Allemagne, Du Khorassan au pays des Backhtiaris : trois mois de voyage en Perse. Paris: Hachette, 1911, vol. II, pp.163–184

General Barziguian, director in chief of the Indo- European Telegraph Company in Tehran, shared with d’Allemagne a collection of photographs taken by a Russian industrialist, Sevruguin, who over a period of 30 years had compiled a remarkable collection of images, subsequently destroyed in 1909 during the fall of Mohamed Ali Shah when looters raided houses owned by Europeans. Some of these photographs were utilised by Jacques Bizot, general inspector for finances, who was at the disposal of the Persian government between 1908 and 1909 and was assigned with the task of reorganising the Persian administration.

Thanks to his materialistic and artistic approach to the objects, Henry-René d’Allemagne contributed to numerous collections of his time, which he compiled in a manner and a format personal to him. He is the author of several important publications that remain of interest to anyone approaching the art of curiosities and collecting arts, thanks to his great passion for the object itself along with its context and period.3Henry-René d’Allemagne, La Maison d’un vieux collectionneur. Paris: Gründ, 1948, 2 vol.

He is also one of the greatest specialists of his time on the history and art of ironwork and locksmithing, from the Middle Ages and the Renaissance through to the 17th century, his historical knowledge being combined with training that was initially theoretical after completing his thesis at the Ecole des Chartes, and deepened by a rigorous practical learning from 1885 to 1890 in the workshop of one of the most brilliant art locksmiths and restorers of his time, “the iron sculptor” Pierre-François Boulanger. Boulanger was known mainly for creating masterpieces of the utmost artistic locksmithing, along with remarkable works like those decorating the central gate of Notre-Dame de Paris, laid out under the supervision of Viollet-le-Duc in 1867 after 12 years of craftsmanship.4“Les portes de Notre-Dame” (“The Doors of Notre-Dame”), in Le Petit Journal. Daily newspaper, Saturday 24 August 1867, p.3 From this rather technical training, d’Allemagne benefited from a knowledge so strong that he could now appreciate meticulous original creations in the context of an unmatched historical and practical approach, placing him at the peak of his art. In 1899 he was entrusted with organising the luminary section of the Paris World Fair. During the 1900 Paris Exposition, he organised the presentation of ancient locksmith crafts, as well as the luminary museum and the toys exhibition.

Henry-René d’Allemagne wrote numerous books on the history of ironwork, on locksmithing from the 12th to the 18th century, on ancient master locksmiths, on the history of luminaries from Roman times to the 19th century, and on the history of toys. He also wrote extensive and very well documented reports on the Paris World Fairs, on sports and skill games, on society games, on recreational activities and hobbies, on playing cards from 14th to the 20th century, on clothing accessories and on furniture of the 13th to 19th centuries. He was also the author of books on followers of the Saint-Simonian movement, on Barthélemy Prosper Enfantin, on printed canvas, on cloth specifically designed for slave-trading, and on the arts of Islam. Many of his fundamental works are still today considered some of the most important ones. He was a member of the Société des Antiquaires de France (Society of Antiquaries of France) – of which he would become president in 1927. He was also a member of the renowned Société des bibliophiles françois (a society dedicated to book enthusiasts) from 1908.

The aesthetic and figurative roots of Orientalism in France date from beyond the 16th century. Since the foundation of the Franco-Ottoman alliance in 1536, King François 1st (1494–1547) sought to form a bond with the Turkish Sovereign of the Ottoman Empire, Soliman the Magnificent (1494–1566), with the intention to face the House of Habsburg and pave a new way towards the Orient. This alliance lasted for more than two and a half centuries until the French Campaign in Egypt, then an Ottoman land that Napoléon invaded between 1798 and 1801, under the pretext that Mamluks had rebelled against the Sultan. This alliance allowed the Orient to influence France enormously, and vice versa.

French humanists made numerous journeys and trades with the Ottoman Empire, amongst whom Guillaume Postel (1510–1581) and Pierre Belon (circa 1517–1564) were active members. The Collège des lecteurs royaux, now known as the Collège de France, was created, allowing Oriental languages to gain a certain popularity. Notable literary works about the Ottoman Empire emerged. In 1561 Gabriel Bounin published La Soltane, a tragedy highlighting Roxelane’s part in the execution of Sehzade Mustafa, Soliman’s elder son, in 1553. Thanks to this tragedy, a representation of the Ottomans was seen in France for the first time. And finally, international trade developed, generating numerous exchanges with the Orient and importing much appreciated exotic goods and objects.

Fashions of the Orient also became popular, such as Turqueries (Turkery), works of art representing the Turkish world in many fashions, an enthusiasm encouraged by the multiple journeys and great discoveries being made. During the second half of the 17th century, the diplomatic mission of Soliman Aga, the envoy of Sultan Mehmed IV (1642–1693) to King Louis XIV in 1669, generated a great deal of interest. The luxury displayed by King Louis had very little effect on the Turkish ambassador, generating a quid pro quo and stirring negative consequences. Such misfortune would be at the centre of the creation of one of Moliere’s masterpiece, Le Bourgeois gentilhomme (The Bourgeois Gentleman).

The strong interest of the Royal court and city for the Orient was further encouraged by the publication of One Thousand and One Nights by Antoine Galland between 1704 and 1717, followed by Montesquieu’s Persian Letters (1721) and Voltaire’s Zadig, or the Book of Fate (1748).

Another milestone was reached in this fascination for the Oriental world with the French Campaign in Egypt from 1798 to 1801, when General Bonaparte tried to seize control of this country, and more widely the Orient, as well as preventing England from using the sea route to India. And finally, the last major event that contributed to this interest was the Greek War of Independence from 1821 to 1830, during which Greece, supported by Russia, England and France, freed itself from the Ottoman Empire’s domination. Lord Byron, a major figure in the Orientalist literature, was amongst the most distinguished philhellenes, and his example would be followed by Chateaubriand, Larmartine, Nerval, Flaubert and others. As for painting, Ingres, Vernet, Delacroix, Decamps, Chassériau, Fromentin, Gérôme drew their inspiration to some extent from a real or imagined Orient.

Émile Prisse d’Avennes (1807–1879), a civil engineer and archeologist known by the name of Edris-Effendi, was a distinguished figure in Oriental studies, the arts of Islam and the Oriental Middle Ages, as well as a brilliant Egyptologist. With photographer Édouard Athanase Jarrot (1835–1873), he used photography to make a systematic account of Egyptian monuments. From 1850, with a brand-new approach that was extremely precise and rigorous, he drew up a prodigious photographic documentation of the monuments he had studied. For two whole years, Prisse d’Avennes and Jarrot documented and photographed a number of important monuments, first in Cairo, and then in Middle and Upper Egypt.

Orientalism in France reached its peak thanks to the contribution of eminent art historians like Gaston Migeon (1861–1930), Émile Molinier’s attaché and curator of the Louvre museum. With true foresight, he was a fervent advocate for the creation in his museum of a section dedicated to the arts of Islam, thus allowing these major arts to enter this noble institution. From his travels in the Orient he brought back objects that would gain a certain value thanks to important and resounding exhibitions, fuelled by the very practical knowledge he gained there, allowing major works of Oriental art to be considered as equals with Occidental masterpieces.

Henry-René d’Allemagne takes full part in this ancient and esteemed tradition; he is one of the most enduring and eminent scholars of Orientalism, benefiting from his field experience as well as his extraordinary knowledge of the vernacular culture. He contributed significantly to expert knowledge of the Orient. He was an enlightened collector and generated a strong enthusiasm for the Orient, influencing many followers through multiple articles, exhibitions and publications as well as his much appreciated sharing of knowledge and images.

This archive enshrines its author amongst the most remarkable and influential proponent of the “Muslim arts” in France, and thanks to its exceptional documentary value this set of photographs sets a crucial ethnographic milestone in the studies of societies and cultures of the people of Central Asia, of Turco- Persians and Iranians.

Alongside this exceptional set of photographs, we offer the following publication:

Allemagne (Henry-René d’). Du Khorassan au Pays des Backhtiaris : trois mois de voyage en Perse (From Khorassan to the Land of Backhtiari: three months of journey in Persia) par Henry-René d’Allemagne, archivist and paleographer, librarian at the Library of Arsenal, leader of the archeological mission in Persia. Publication containing 960 photographs within the text and 255 out-of-text prints, 47 of which printed in colour. Paris: Hachette, 1911, 4 vols of 228, 250, 271 and 323 pp. Size: 33x27cm. Aubergine purple half-calf binding, spine ribbed with golden titles and volume numbering, untrimmed, well preserved polychromatic cover and back (modern bookbinding).

Original edition of this important and superb account of an archeological, artistic and photographic journey in Persia in the early 20th century, undertaken by order of the French government under the supervision of one of the most distinguished scholars of the period. This book contains, much like an encyclopedia, extremely detailed information on all aspects of culture, traditions and Persian civilisation.

Although the title of the publication mentions “960 photographs and 255 out-of-text prints”, only 816 images are on-site photographs, mainly general views, architectural or of objects. The other images are reproductions of drawings, prints or objects from the personal collections of the author. This archive contains half of the images made to illustrate this publication, 379 out of 816 photographs, including 60 out-of-text images out of 156.

Printed in 510 copies, this being one of the 250 numbered prints (no. 41) in wove paper.

For further information about the collection, please contact Bruno Tartarin.