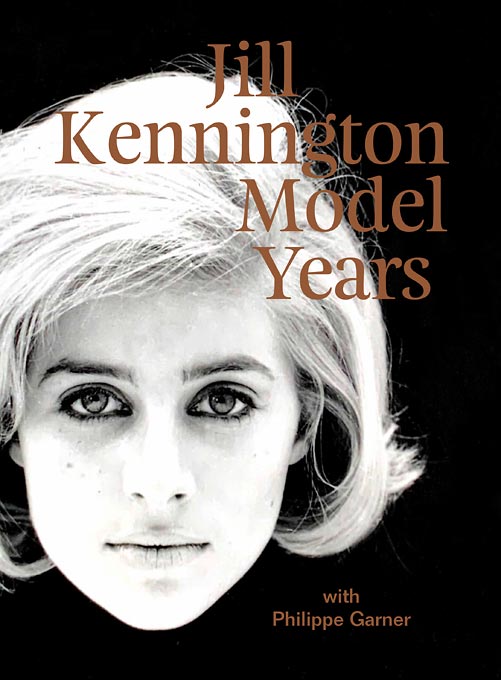

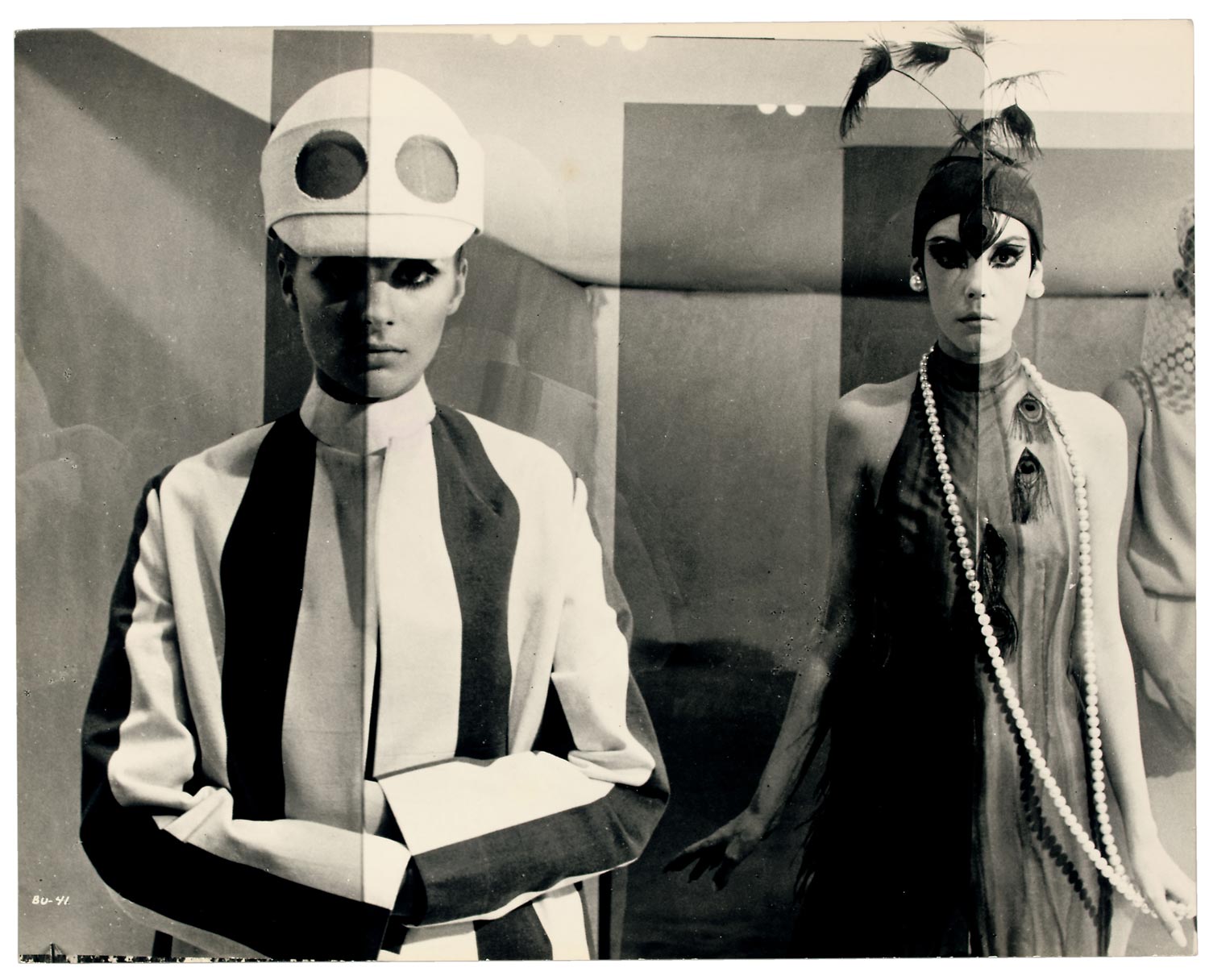

The British model Jill Kennington was dubbed Vogue‘s ‘Young Idea’s ’63 quintessence’. She became one of the most successful models of her generation, embodying a fresh, youthful, and dynamic ideal of beauty that came to define the Sixties, and she was also cast for Blow-Up, Michelangelo Antonioni’s film that for many has come to define that exciting London moment. Hot off the presses is Jill Kennington Model Years, a memoir that takes the form of an extended interview in which she responds vividly and with disarming frankness to questions from fashion photography historian Philippe Garner, who initiated and shaped the project.

Chapter titles such as ‘To Turkey for Elle’, ‘To the Arctic for American Vogue’, ‘To Kenya with Peter Beard’, and ‘Cast for Antonioni’s Blow-Up’ give the flavour of Jill’s professional experiences through those heady years. She describes her collaboration with some of the greatest photographers of the era, including Richard Avedon, William Klein, Saul Leiter, Helmut Newton, and Norman Parkinson; and she shares her memories of a remarkable cast of characters that includes Federico Fellini, Norman Hartnell, David Lean, Mary Quant, Vidal Sassoon, Terence Stamp, and Veruschka.

Beyond Jill’s precious insights into the worlds of fashion, modelling, film, and photography, this memoir is also a poignant account of intense emotional challenges and dark episodes in the rollercoaster of her private life – a moving and inspiring story of a young woman’s journey to self-awareness.

I met up with Philippe Garner in his home in north London to discuss the book and began by asking when he first became aware of Jill Kennington.

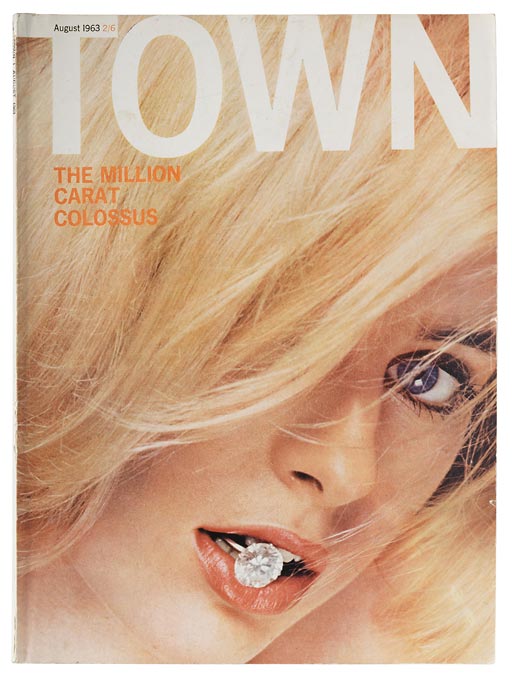

– I was something of a magazine junkie in the Sixties. I drew so much information and inspiration from them regarding many areas of the arts and that included, very much so, fashion, style, and related magazines. If you were interested in the subject, you couldn’t help but become familiar with the top models. And Jill was, to me, the most striking, the most attractive. She had a dynamism that was uniquely hers. So I was already well aware of her in the Sixties. I was cutting her pictures out of magazines, keeping certain complete issues in which she featured prominently. In a sense, that’s where the book began, over half a century ago. I rated her so highly. It was the look – the self-assurance, the strength, the energy of that look. She had more than simply great photogenic bone structure; it was the way she projected herself, so dynamically, in the photographs. Her impact on the page was just so powerful and so emblematic of that time.

Fast forward to 1991, the time of the exhibition Appearances at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, a big retrospective on post-war fashion photography. They had a week of lectures and I had committed to give a couple of talks. I then had a call from the museum, and they had in mind to invite a model to talk about her experiences of the Sixties. They had approached Jill Kennington, but she was reluctant to give a talk as such, though would be willing to talk ‘in conversation’. Would I be prepared to be the person to ask the questions? Of course, I leapt at the opportunity! I met Jill ahead of time, saw a lot of her cuttings. I saw material I knew, but also much that I didn’t know. I was particularly struck by the great pictures she had made with John Cowan, many of them made for the newspapers – pictures that had a lifespan of one day and, for that reason, hadn’t entered the canon of fashion photography. We got on well and the ‘in conversation’ happened at the V&A, but more conversations followed, and that led to me investigating the life and work of John Cowan, which led to a book and an exhibition at the V&A in 1999. My friendship with Jill continued and grew and she would occasionally help me on other research. I started working on an exhibition and then a book about Blow-Up and she gave me insights, having had a role in the film. And all the while she would say, ‘Oh Philippe, one of these days we must tell my story,’ and I would say, ‘Yes Jill, but you should just start jotting things down – a thought that occurs to you, a memory that comes back. Don’t sit at the screen or in front of a blank sheet of paper worrying how to begin, as if you were trying to compose the first line of War and Peace.’ ‘Yes, yes…’, she would say; but it didn’t happen.

So how did it happen eventually?

– When the book on Blow-Up came out, I was asked by Vanity Fair if I would do something for their website, interviewing someone who was in the film. I proposed that I interview Jill and they said, ‘Perfect!’ There was a degree of time pressure and I said to Jill, ‘I’m in town; you’re in the country. We won’t have time to get together and we need to get it done quite soon. How about doing it by email exchange? I send you a question, you send me the answer. We’ll knock it on the head in twenty-four hours.’ That’s what we did. Jill’s first answer came back; more questions, more answers. I tidied it up, polished it, delivered it. Vanity Fair was delighted. Then I called Jill and said, ‘We have found our method to tell you story. I’ll start with a question about your earliest memories of your childhood and we’ll take it from there.’ And that’s what happened

How long did it take?

– It happened over a period of years. There were times when it ground to a halt. Perhaps I had asked a difficult question, for instance about the challenges she had faced in her life with John Cowan. At times, she had to take a deep breath and get in the right frame of mind to be able to write about certain things. But other answers just flowed so effortlessly. My questions were short and to the point. Her answers generally came back within a few days, sometimes within twenty-four hours. Her answers were vivid, immediate, spontaneous. It was as if she was in the room telling me that story. There was no attempt to write in a literary style, I’m pleased to say. I realised it was going to be very important for us to keep that conversational immediacy in the end product. Jill would write in a sort of stream of consciousness, casting punctuation, capitalisation, and other such details to the wind. And that was fine; I could follow up and sort that; but I was excited to be getting these recollections, with some great detail. Story-telling from one’s own past isn’t always easy. Some people can be fastidious about dates, others can’t remember what decade it was; some can’t remember detail, only a big picture; but Jill revealed the ability to pull out specific and telling observations – all the way through the book she does that – which so help bring those moments to life.

So it took us a long while. It’s not as if we had a publisher. Also, bear in mind that it’s more than an account of her modelling and working with photographers. It’s the story of her life during those years and to some extent beyond. And there were some darker chapters in that life. Real challenges. Things happened to her that she had never shared and so getting her over the hurdle and ready to talk about those things wasn’t always easy. It just took time. Sometimes, we would get together and I would ask, ‘What’s blocking you?’ and she would say, I’m not sure I can talk about that?’ And I would say, ‘Think of it like this, that it’s a legacy for your daughters. Imagine that it’s only destined for them and they surely will want you to tell it as it was.’ And she did want to tell the story in its fullness, but understandably didn’t always find it easy to face up to certain things that had happened, to acknowledge them; but she did. I’m thrilled to say that when her daughters eventually read it, they were emotional, and truly delighted. By that stage, Jill was coming around to asking, ‘Are we going to turn it into a book?’ And eventually, she was ready to share her story in full with an audience.

What was the next step?

– It was then for me to figure the shape and feel of what would make sense as a book. Having conducted it in the form of an interview, my instinct was that it should remain in that form, not to remove my questions and turn it into one, unbroken text. I remember taking it to a publisher who said, ‘Oh, it’s in a most unusual format. We may have to rethink that.’ But I wasn’t going to rethink it. I believed in it. Eventually, I found a small publisher, Unicorn, who thought it was a great project and were willing to give themselves to it.

I like the way that the illustrations are scattered throughout the book and matched to the chapters.

– I have read many memoirs and biographies where the images are clustered in the centre of the book or in two folios, poorly reproduced, and you have to go backwards and forwards to match pictures to text. It was my absolute determination that we should create a kind of a hybrid. It’s not a picture book; it’s text-led, but I wanted it to have the quality and feel of an art book. And I wanted whatever images we selected to illustrate it to be powerful on the page, and each would have its own page, and would fall where Jill is talking about it. That was a non-negotiable aspect of it from my point of view. I also did my best to reference the specific publication details of every shoot that Jill discusses. A few proved elusive, but the great majority are there as footnotes, making it a more helpful resource for any researcher.

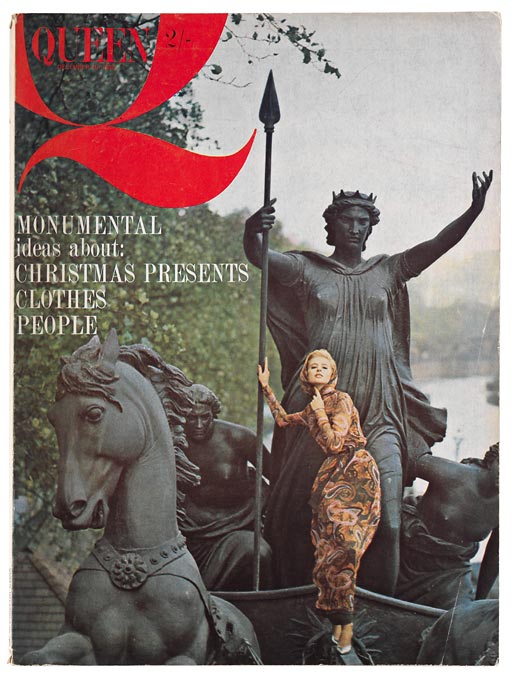

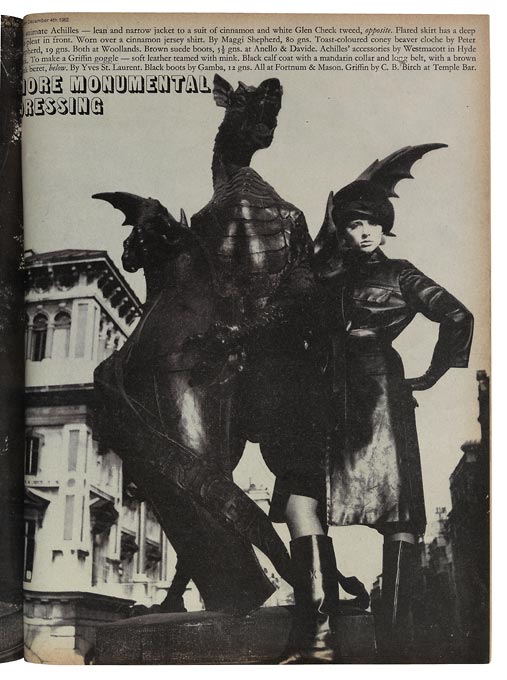

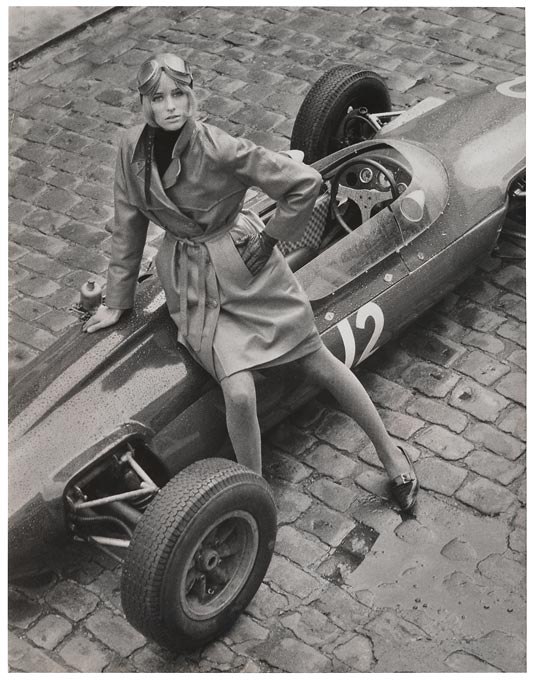

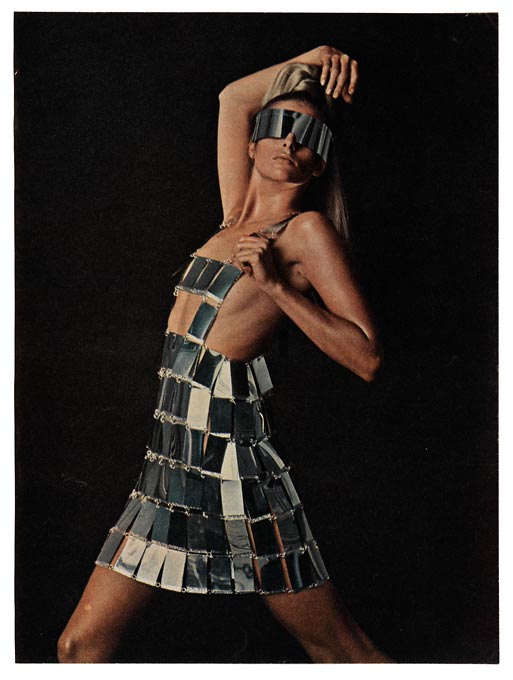

I enlisted the services of a talented book designer, Stuart Smith, with whom I had worked on a previous project and we collaborated very easily. We didn’t want the book to look ‘designed’, just to look clean and simple and legible. And a lot of books don’t meet those criteria. In terms of the illustrations, it felt right that, as far possible, we should illustrate period documents, by which I mean I preferred to show a period print or the original magazine rather than a modern print of any image. I was pleased to reproduce newspaper cuttings with ragged edges. They were the physical traces of a life, of a career, for the reader to be reminded of how Jill, through those photographs, engaged with her audience at the time. I think it gives the book a particular character. I believe it’s a powerful dimension of the book. As well as the cuttings, the tear sheets, there are also a few personal pictures, including two images of her passport – with her passport photograph taken by John Cowan and the stamps to remind us of her extraordinary travels during those years – and her portrait of her daughters.

It’s her memoir but it also tells a more complex story, and captures the zeitgeist.

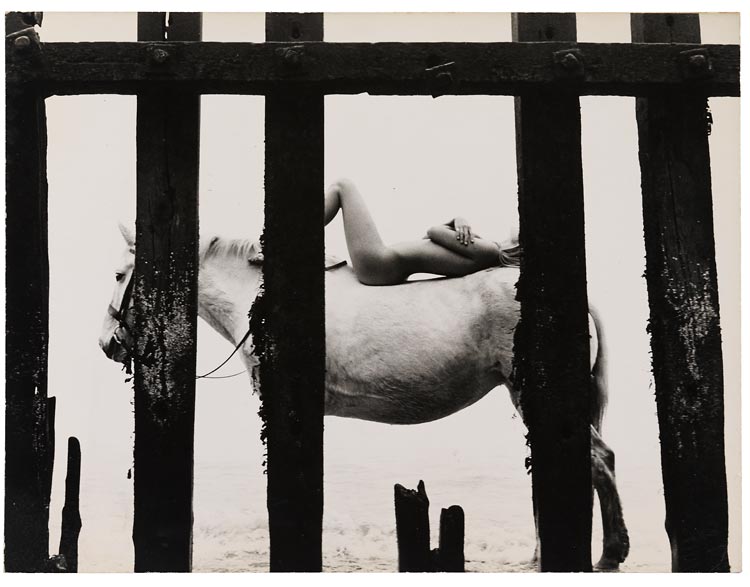

– I think the book manages to be several things at once. It’s a social history, it’s a personal story, the ups and downs of a life that was not as easy as the glamorous images might have us believe. It’s also a wonderful photographic document because of her vivid accounts of working with some of the greats – a protagonist’s account. She was part of the process, and we have, in no particular order, John Cowan, Helmut Newton, William Klein, Saul Leiter, Richard Avedon, Guy Bourdin, David Bailey, Norman Parkinson, John French, Bert Stern, Bob Richardson, David Montgomery; the list goes on. It’s a hell of a roster, of the Sixties going into the Seventies. And she manages very effectively to convey the individual character and methodologies of each photographer, some calm, some more excitable. Laid-back David Montgomery contrasts with the energised Richard Avedon. All those nuances are just fascinating, as are her specific memories of the various studios. That said, Jill was first and foremost a location model, and at her best out and about, on horseback, on a camel in the desert. She gives a detailed account of her trip to the North Pole with John Cowan, for Diana Vreeland and American Vogue, and of her shoot with Peter Beard in Kenya for Queen. Jill was fearless. She would perch on high sculptures around London, put up there by a cherry-picker. And she would give so much to the shoot. She was the antithesis of the static model who would need to be precisely instructed, like a marionette being put into position. Jill had an energy that she wanted to invest fully in the situation; and with the right photographer, working as a team, something dynamic and compelling would emerge.

This is also a remarkable travel book because Jill really criss-crossed the globe, from the North Pole to the South Pacific. There’s one chapter called, ‘From fur coats to a sarong’, which gives a hint at this aspect of the book. This was way before the age of mass tourism. In the Sixties, I would guess, only a relatively small number of Brits had a passport. And yet Jill was often away and loved the adventure of travel. Her professional story starts in London. The London scene and its characters are well evoked, but at the tail end of the decade, she moves to Paris for a while, before going to Rome. Apart from the exotic travels, we have some very interesting insights into her years elsewhere in Europe. Those were strange times in Rome – decadent, flamboyant, sinister. We are talking of the years marked by such events as the kidnapping of J. Paul Getty’s grandson.

You mentioned her energy, that she was first and foremost a location model. Is it true to say that the images taken by John Cowan, who put a lot of energy into his work, alerted other photographers to what she could do?

– I think that’s true. In a sense, she discovered and defined her strengths working with John Cowan. She started out doing fashion-house catwalk modelling, for Norman Hartnell, and soon decided that it wasn’t for her. It was the photographic modelling that was going to be her path. And very early on, in ’62, she met John Cowan. It was like a match to a flame. They ignited a relationship which became personal after a while, but was initially a terrific professional relationship. Cowan was a great adventurer who felt claustrophobic in the studio. His first instinct when given a job was to figure how to energise it. Jill, who had been brought up on a farm, was very comfortable on horseback and described herself as having had an ‘outward bound childhood’. She was ready to take calculated risks. She and John were a perfect complement to each other. So I think you’re right. That work defined, for herself and for others, what jobs she was going to be suited to. Not that she couldn’t do stylish studio work; but she was so much more in her element as a location model. Perhaps we should add an extract from the book, to hear Jill’s account of one of these inspired shoots.

Yes please. Among the many fascinating chapters in the book is ‘Cast in Blow-Up‘. Antonioni hired John Cowan’s studio for the studio scenes in the film. Cowan would also partly inspire the David Hemmings character.

– Jill talks in some detail about Blow-Up and the various influences that she could see in the Hemmings character, including of course John Cowan. Having signed up to appear in the studio fashion-shoot scene in the film, when it actually got underway she felt uncomfortable because she was asked to be as stiff and formal as a shop window mannequin. This was alien to her, and not her way of working. She was unhappy about this during the filming. With time, she was immensely grateful that she was cast for the film, a film that has become such a cult classic.

Some models have expressed regrets or ambivalence about their years in the business. Did she ever regret going into modelling?

– I think the simple answer is no. Going into modelling gave her extraordinary opportunities. She seized and made the most of them. I don’t think she has any regrets about the modelling years; they were remarkable years for her.

Jill Kennington Model Years is published by Unicorn Publishing Group

Excerpt from Jill Kennington Model Years:

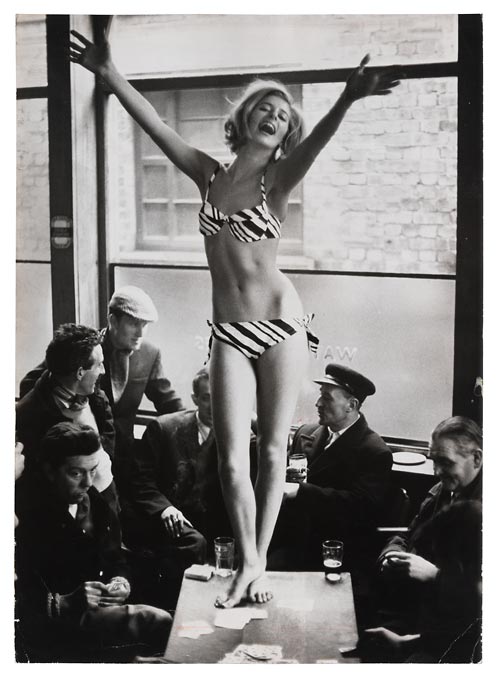

A couple of weeks later, John had me standing in a bikini on a table in The World’s End pub on the King’s Road, surrounded by guys playing cards and drinking their beers. This was for a Daily Mirror feature, ‘What happens when a photographer plans to shoot swimsuits outdoors and it rains?’1April 3rd 1963 The shoot was a perfect example of the great ideas and impulsive energy generated when I teamed up with John. Totally necessary was the collaboration of a good fashion editor who, having shown us the outfits, was then able to run with an idea, allowing our creative input. Felicity Green, on the Daily Mirror, was one such editor with whom we developed many original concepts. For this particular shoot, there was no budget to take us to the South Seas. It was cold, raining, and still wintery in London. We were planning to go to Chiswick, but the filthy weather stopped us. John’s Land Rover, which often doubled up as the dressing room, had on board the necessary bikinis, make-up and photographic equipment, as well as myself and the other model, Finola, an assistant, and Felicity as fashion editor. All of us were frustrated that our original destination wasn’t viable. In desperation, we pulled over in the King’s Road, at World’s End, and went into the pub for a think. It occurred to John that, given permission, we could use this wonderful old pub – all wood panels and mirrors – as our location. Whose idea was it for me to stand on the table? I don’t remember; however this is what happened. A huge problem to start with was the ogling customers, but these workmen were easily bribed with pints of beer not to look, to carry on talking to each other, and to concentrate on their card game. So, I remember following my usual plan, focusing only on working for John and not taking notice of anything outside of that. There is a frisson about these pictures, free and abandoned and joyful, in a completely unlikely setting. I’m happy to say, we achieved truly high-voltage pictures.