I have written somewhere else about Antonia Gotte1Denis Pellerin, History of Nudes in Stereoscopic Daguerreotypes – Collection W. + T. Bosshard, 2020. The book was published simultaneously in English, French and German. but since then I have found some unpublished facts about her life as well as some new stereoscopic images of this much photographed model. I therefore thought I would have another go at her biography, using the scant information available.

Antonia was born Adèle Gotte at Montrouge, near Paris, on August 13th 1837. Her father, Maximilien Joseph Gotte, born at Remagen, near Koblentz, Prussia, in 1807, was a conductor for “Les Favorites”, one of the several competing omnibus companies that operated in France before they were amalgamated into one unique entity in 1855.2Known as Compagnie générale des omnibus it operated 25 regular lines by 1856, all designated by a letter of the alphabet. On July 9th 1835 Maximilien married a thirty-one year old laundress, Véronique Virginie Compain, who was three years his senior and had already been married then widowed. They seem to have had only one child, Adèle, who was barely one and a half years old when her mother passed away on December 15th 1838. Just over three months later, on March 18th 1839, her father, who had by then become a coachman, remarried. His second wife, Marguerite Virginie Chenevière, was a child carer and had probably looked after Adèle after her mother had died. It is to be supposed she had done a good job of it and was fond enough of the child for her father to take her as his wife.

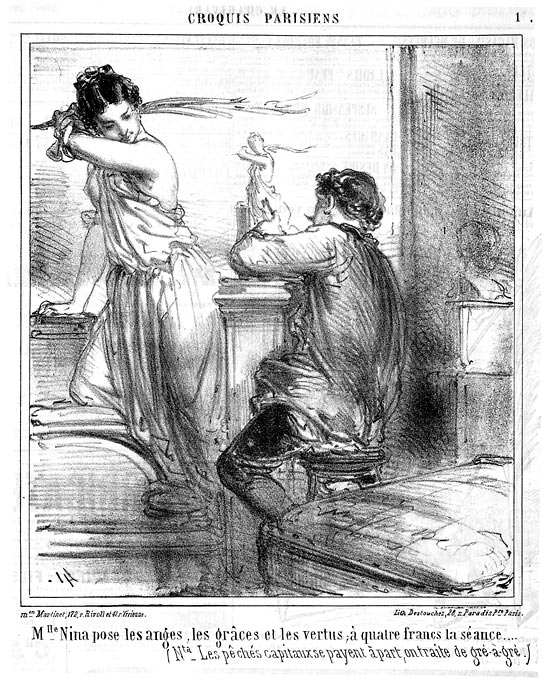

Nothing else is known of Adèle’s childhood but we can assume she grew up into a rather pretty teenager, was noticed, and started modelling for artists. It must be at this point she started using the more exotic and romantic name Antonia, instead of the one she had been given at birth. She soon became a professional model and appears to have been very much appreciated in the artistic milieu where she was known as “the Fair Antonia”. It can be supposed that, like Nina in the lithograph below, she posed for angels, graces and virtues at four francs a sitting and probably also for Venuses, Phrynes or Galathaes for a higher salary.

At some point in her modelling career Antonia accepted to sit for photographers and used as she was to unveiling for painters did not think twice before doing the same in front of the camera. But, as she was soon to learn at her expense, sitting in the nude for a painter who used the excuse of Mythology or of the Bible to represent women in their birthday suit and elevate them to the status of goddesses, nymphs or biblical figures was very different from taking off one’s clothes for a photographer. Painting and Sculpture, however thin the pretext was for showing women in a state of nature, idealised the models. Through the medium of the brush or the chisel they became nudes, they were Art, and could consequently be exhibited in public without anyone finding fault with them. The camera captured the models as they really were, that is women who had taken off their clothes. They were not nudes, they were simply naked flesh, and therefore indecent and reprehensible in the eyes of the prudes and of the law.

Some time around 1857 Antonia started working for photographer François Antoine Lepage (Paris, May 15th 1836 – Paris, February 11th 1893) who had a studio rue du Four-Saint-Germain. Lepage was arrested by the Police des Mœurs (Vice Squad) on August 12th 1857 while trying to sell seventy-two daguerreotypes showing women in various states of undress not very far from where he operated. He was forced to reveal the names and addresses of his female models and soon afterwards some policemen repaired to 13, rue du Pont Louis-Philippe, where Antonia resided, and arrested her. She was tried by the seventh chamber on September 8th, along with Lepage, his associate Xavier Merieux and seven other female models: Augustine Guy, Christine Solari, Amélie Rolland, Aglaé Antoinette Brunel, Adèle Buffet, Pauline Sophie Lacroix and Fanny Decors. Antonia’s natural poise and grace must somehow have stood out for two of the journalists who reviewed the trial commented on her beauty. One, from Le Droit, described her face as “remarkably pretty”3Le Droit, September 9th 1857, p. 2., the other, from La Gazette des Tribunaux, said of her that she was “known in artistic circles as the Fair Antonia, a nickname which is amply justified”.4La Gazette des Tribunaux, September 9th 1857, p. 895. Both also noticed that, from the start, Antonia looked restless, even agitated. She had a fit of hysterics just before the proceedings began and had to be carried out of court. Later in the day, when she heard she was being fined one hundred francs and sentenced to a fortnight’s imprisonment, she fainted on the bench where she was sitting with the other accused and had to be carried out again. When she came back to her senses she had another fit of hysterics. The newspaperman from La Gazette des Tribunaux wrote that “four of five people could hardly contain her and her screams could be heard throughout the Palais de Justice”.5Idem. Oddly enough the same journalist refers to Antonia as Mrs Lebon. It is the only suggestion I have found so far that she could have been married. Neither her police file nor her prison register mentions her alleged husband so it is my assumption that she only pretended to be married to ward off some of her more daring admirers and suitors. To go back to her trial, we must try and understand Antonia’s shock on realising she was being sentenced to some time in prison for doing exactly what she must have done several times before for painters, and we cannot but excuse her extreme reaction. Out of the eight models on trial that day, she was the only professional sitter and had previously been praised both by the artists and by the public for her curvaceous body and her beauty. To find herself suddenly accused of indecency – outrage à la morale publique was the exact charge in French – and treated like a common criminal must have been too much for her.

Although she had been sentenced to fifteen days’ imprisonment, Antonia, for a reason which is yet to be determined, only spent a week at Saint-Lazare, the only prison for women in Paris. Most of the young women who had been tried with her were incarcerated before September was over but Antonia arrived at the prison on Monday November 2nd 1857. Did she fall ill after her fit and was she sent somewhere to rest until she had recovered? We shall probably never know. Her name and details were entered in the prison register under record number 1969. She was measured and her description was written down before she was made to don the prison uniform. That is how we know she was 1.58 metres tall (5 foot two inches), had chestnut hair and eyebrows, brown eyes, an oval face, a low forehead, average-sized mouth and nose, a round chin and a fair complexion. I very much doubt anyone reading this dry and unpoetic record would recognize her in the street, or on a photograph for that matter, or have an idea of how pretty she was, but that was the way repeating offenders were supposed to be identified before “Bertillonnage” – the Bertillon system – and afterwards fingerprinting were introduced. It is a pity we do not know anything about Antonia’s stay in prison, but judging from her reaction during the trial it cannot have been a pleasant experience for her. Antonia was released on November 10th and went back to modelling but she must have kept her clothes on, or at least covered her body within the limits of what was considered “decent” at the time, as her name is not mentioned again in the police files or in the judiciary press. We know she sat for photographer Eugène Thiébault (Metz area, February 25th 1826 – Enghien-les-Bains, March 24th 1880), as is evidenced by the photographs below.

It is not clear at which point Antonia put an end to her modelling career. A unique sentence published in Le Figaro on November 15th 1867 reveals that she was hired as an actress and/or singer at the newly opened Athénée Theatre.6Le Figaro, November 15th 1867, p. 4. “Mademoiselle Antonia Gotte est engagée au théâtre de l’Athénée.” (Miss Antonia Gotte has been hired by the Athénée Theatre). Nine words, and that’s it ! Not much to go on, is there ? The strangest thing about this announcement is that Antonia is introduced as if everybody knew of her. Yet, her name does not appear before or after in that particular newspaper. Originally built in 1865 in the basement of a large house at 17 rue Scribe by banker Bischoffheim to hold concerts and lectures, the room was enlarged in 1867 and turned into a theatre that could accommodate 900 spectators. The first performance took place on December 13th 1867. Although such composers as Georges Bizet, Léo Delibes and Charles Lecocq had some of their works performed there, the venture was not a financial succcess and the first company that occupied the Athénée was out of business by January 1869. Since I could not find any other trace of Antonia’s acting career in the press of the time it is difficult to know how long she graced the stage with her presence and with no later photographs of her it is equally impossible to get an idea of how kind, or unkind, time was to her.

Antonia died on November 9th 1885 in the house of one Mr Henry at 6, rue d’Aumale in the ninth arrondissement of Paris. Her death certificate bears the name she was given at birth and the one she chose for herself: Antonia Adèle Gotte. She must have been lying to her friends and acquaintances about her age since the witnesses as well as the three death notices I found in the press7La Patrie, November 13th, 1885, p. 4, Le Constitutionnel, November 13th, 1885, p. 4, Journal des débats politiques et littéraires, November 14th, 1885, p. 4: “Mlle Gotte, 40 ans, rue d’Aumale, 6.” describe her as a forty-year old woman though she was actually forty-eight when she passed away. I think she can be forgiven this final touch of vanity which was then very common in artistic milieux (and still is, I am told).

Up to now Antonia was only remembered through dozens of stereoscopic images on plate or paper. I hope this short article will have given her another lease of life as well as a real presence as a person, not just “a pretty face”. She was born in humble circumstances, like most of her fellow models, but her natural elegance and grace – something no amount of money can buy as is evidenced daily in hundreds of photos of celebrities – make her instantly recognisable. It gives her a special place in the pantheon of young women who unveiled for the camera when there was a high price to pay for doing so.