In the summer of 1898, over 500 citizens of 35 Native American nations gathered in present-day North Omaha to participate in the Indian Congress. Some had travelled over 800 miles to get there. The unprecedented convening coincided with the Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition, Nebraska’s world fair. Over two million fairgoers viewed Expo displays showcasing American agriculture and industry. They also toured Native American encampments and attended Wild West shows, events that entwined anthropology and entertainment. Marking the end of a devastating century of federal policy, fair organisers intended to celebrate the United States’ expansion into Indigenous territories.

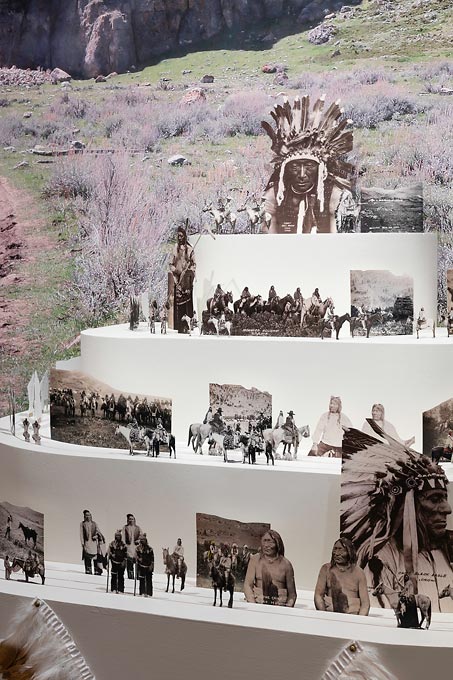

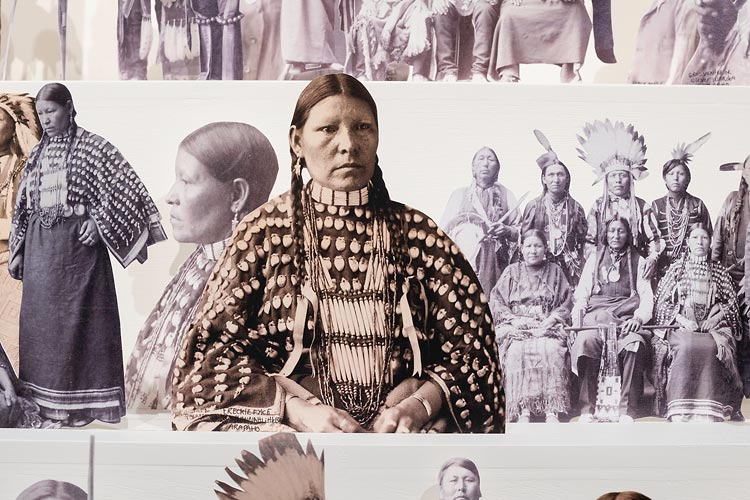

The complex historical dynamics of 1898 Indian Congress were examined in The Indian Congress 2021, a site-specific installation by Wendy Red Star at the Joslyn Art Museum in Omaha, 30 January – 25 April 2021, with a life-size Expo booth of the kind that displayed farm produce, accompanied by American flags and fanfare. But instead of apples and potatoes, Red Star arranged hundreds of meticulously cut out photographic reproductions of Indian Congress members’ portraits taken by Frank Rinehart (1861 – 1928) in his studio in downtown Omaha. Exceptional for the time, Rinehart recorded these individuals’ names and tribal affiliations, preserving an invaluable record of delegation members and their families. Grouped by sovereign Native nation on tiered display tables spanning the gallery’s length, the portrait cut-outs manifesting the magnitude of this Indigenous gathering.

Wendy Red Star, born 1981 in Billings, Montana, is of Apsáalooke ( Crow ) and Irish descent. She works across media to explore the intersections of Native American ideologies and colonialist structures, both historically and in contemporary society. Her installations and photographic practice build upon years of research in photographic archives and museum collections of historical Apsáalooke artwork. Montages from her Accession series entered the permanent collections of of MoMA and the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in 2020.

Many citizens of the Apsáalooke Nation posed for Rinehart, including White Swan, an artist and U.S. military scout whose larger-than-life portrait was placed at the entrance of the installation. Rinehart’s images are preserved in the Omaha Public Library Archive. Through the intimate process of cutting out reproductions of full-length, bust and profile portraits, carefully cutting away the studio backdrops, except for the portrait of White Swan, Red Star acquainted herself with Rinehart’s sitters, their poses and their attire. Was their participation in the Indian Congress a quiet act of resistance? Fair organisers positioned Indigenous people as ethnographic foils to the so-called American progress on display at the Expo. However, Red Star’s arrangements turn this logic on its head by emphasising the agency of the individual and the power of the collective.

A year after the Indian Congress, Rinehart photographed Apsáalooke people on their homelands in Pryor, Montana, Red Star’s home town. Primarily taken by the photographer’s assistant, Adolph F. Muhr, later assistant to Edward Curtis, these stereographs picture community members near summertime gathering locations and culturally significant sites. Red Star positioned this second group of images on a separate table decorated with gold-tipped goose feathers and framed by velvet curtains. Behind it, Red Star’s photo mural depicting modern-day Baáhpuuo (Where They Shoot The Rock), a sacred site and home to powerful beings known as the Awakkulé (The Keepers of The Land ), reorienting gallery visitors within Apsáalooke lands.

Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha, is located just a few miles from where the Indian Congress took place. The Museum, a gift from Sarah Joslyn, in memory of her husband George, opened in 1931. Alongside impressive collections of antiquities, masterworks from the Renaissance and Baroque eras and the leading impressionists, it has renowned collections of 18th and 19th century American art and Native American art and artefacts.

In 2019, Annika Johnson took up her post as associate curator of Native American Art at Joslyn Art Museum. I began by asking her how the Native American programme at the museum has evolved over the years.

– I am the inaugural associate curator of Native American art at Joslyn, a position that was created in 2019 with a four-year grant from the Mellon Foundation. Prior curators had worked with the Native art collection and exhibited a few works in the galleries, though this is the first time they’ve had a Native American art specialist in a position dedicated solely to Native art – which is exciting! My job has three interrelated components – engaging with the community, caring for the collection, and planning exhibitions and interpretation.

What drew you to the field originally?

– I grew up in Minnesota, and it wasn’t until graduate school that I learned that the southern half of what we currently call Minnesota is actually Mni Sota Makoce, Dakota homeland. I began to research Dakota history for a graduate seminar, which led me to study 19th century ethnographic portraits and scenes of Plains peoples, which eventually brought me to the study of Native art. How can we understand Euro-American portraiture of Indigenous people without considering the motivations of the sitters, their cultures, and experiences? It seems natural to me to consider what have mostly been siloed fields of “American” and “Native American” art together, and my research focuses on artistic exchanges and is cross-cultural. I think some of the most exciting research and curatorial work is being done in the field of Native American art, and also with projects that acknowledge Indigenous homelands. This work is collaborative, cross-temporal, and inherently must address the ongoing state of colonization and the implications of this for Indigenous peoples and for the environment. I think that the working being done in the field of Native American art is deeply meaningful.

Can you tell me the museum’s own collections?

– There are approximately 1,700 Native American artworks spanning several regions in North American – from the arctic to the southwest, with a strength in our region, the Great Plains. The dates primarily range from the early 19th century through the present-day, with an emphasis on the late 19th–early 20th century, the reservation era. We have quite a bit of beadwork and quillwork, such as beaded vests, leggings, and moccasins. Alongside ancestral (also oftentimes called “traditional”) arts, we also have modern and contemporary works by artists such as Oscar Howe, Arthur Amiotte, Emmi Whitehorse, and Juanita Growing Thunder.

Is photography an important part of the collections?

– We do not have a large collection of Native American photographers (we have works by Zig Jackson and Wendy Red Star’s Four Seasons series), though the museum is has a small but well-rounded collection of photography. We also have a few photographers related to the American West, such as William Henry Jackson, Edward Curtis and John K Hillers, as well as contemporary photographs by artists such as John Divola and Susan Rankaitis.

Can you tell me about the dialogue you have with native artists and communities?

– Building relationships with Indigenous communities in the region is a major focus of my position at Joslyn. Informing people that the collection is here, and opening it up to Native scholars, elders, culture bearers, artists, and students is a primary goal of mine. My goal is to partner with Indigenous-run organizations as well as artists and community leaders and find ways to activate the collection. For instance, we worked with the Omaha Public Schools’ Native and Indigenous Centered Education (NICE) program to create videos featuring Joslyn’s collection for their students’ remote learning program. I’ve also had several culture bearers come in to look at artworks created by people from their community, and those visits can be incredibly powerful. I also work with Native people on gallery interpretations and programming. There are so many opportunities to meaningfully connect our collections with Indigenous communities, and I am looking forward to future partnerships.