Each stone contained a word of my story;

And I heard booming in my memory

The tumultuous swarm of erased dreams.

— “La Maison démolie”

Du Camp wrote “La Maison démolie”1Les Chants modernes (Paris: Michel Lévy, 1855),138. All translations are mine unless otherwise noted.in April of 1849, six months before his departure for Egypt. The poem tells us that the house being demolished was Du Camp’s own, one that he had inhabited for ten years. It was there, he says, that his longing for travel began, and there, in “questioning innumerable phantoms” from the past, that he “saw the uncertain future set itself apart.”

The destruction of the outer walls uncovers a living organism:

Under siege the house revealed its entrails:

The vigorous workers felled the walls

Which collapsed, covering the ground with their debris;

And each section of wall, toppling at intervals,

Emitted colossal cries as it fell,

Seeming to possess for its lament an immensity of voices.

Du Camp sees his bedroom destroyed, the room “where the image of my mother was suspended nearby,” and where he had passed many hours with his mistress. The poem structures associations of the self, house, and woman – links between male, architecture, and female. Beginning with the image of demolition workers outside of the house, the poem spirals inward to the room of sleep, of the mother, and the lover. What is ultimately described as being destroyed is the protected space of dream and desire, the space of the woman’s body. Yet the poem does not end in despair, but rather on an unexpected note of defiant release: “May nothing remain of my old home!/ May even its name disappear and die!” Du Camp concludes assertively, “My heart is a palace that will not be demolished!”

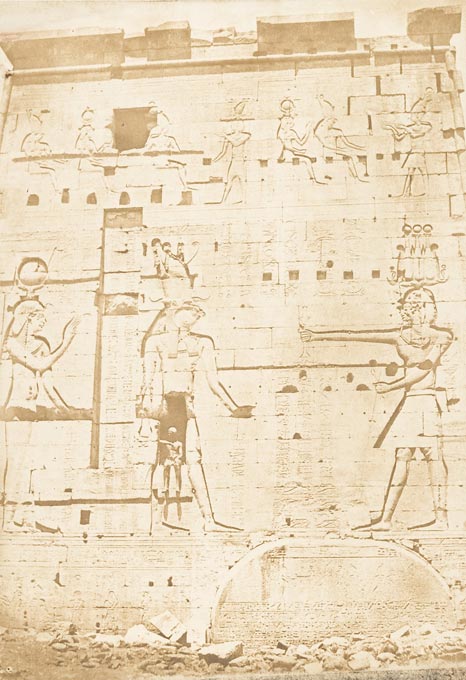

In traveling to Egypt, Du Camp inevitably took with him these contradictory feelings about the demolition of the home. As he confronted the debris of this ancient civilization through his photographs and texts, Du Camp was engaged in the paradoxical enterprise of salvaging it from its threatened oblivion and, at the same time, rejoicing in its very destruction. “Localities play a role in human sorrow, and we cast the shadows of our hearts upon their walls,” wrote Du Camp’s friend Louis Bouilhet as an epigraph to “La Maison démolie,” unwittingly describing what would become Du Camp’s uneasy photographic shadow-play among the toppled Egyptian monuments. It is a play in which Du Camp will situate a living protagonist: a dark male figure tucked here and there in unexpected and often hidden places among the ruins (fig.3). This body, as it is positioned in the crevices and summits of the remains of a monumental past, serves as a cipher for Du Camp’s ambivalence towards the destruction and possible preservation of the past, rendering his vigorous conclusive note of autonomy in “La Maison démolie” paradoxical.2In a recent essay I have discussed the pictorial implications of this body within the context of staffage figures in travel prints and photographs, and in terms of the conservative aesthetics of the Paris Salons as seen in Du Camp’s reviews of the 1850s and 1860s. See “The in visibility of Hadji-Ishmael,” The Body Imaged, ed. Kathleen Adler and Marcia Pointon (London: Cambridge University Press, 1993).

An intense, hyperactive, obsessive worker, Du Camp had prepared extensively for his journey, planned since his early youth. Placing himself within a Western tradition dedicated to the preservation and recovery of the past, he had copied long extracts from the travel accounts of the Greeks and Romans such as Plutarch and Pliny, as well as passages from eighteenth- and nineteenth-century scholarly and travelogue works of all kinds. He had also kept abreast of the more recent archaeological discoveries of Belzoni, Lepsius, Wilkinson, Prisse d’Avennes, and others. He would follow the itinerary of Champollion, the great decoder of the Rosetta stone.

Once in Egypt Du Camp worked with manic persistence. He hired an Egyptian scholar in Cairo to instruct him on the customs of Islam. He kept an extensive, detailed journal with tenacious regularity and accumulated reading notes, before and after his trip, résumés of existing archaeological and ethnographic accounts. He paid great attention to classification, even making alphabetical indexes to his own handwritten notes.3These indexes and notes are in the Du Camp archives in the Bibliothéque de l’Institut de France, Paris: Manuscrits et papiers inédits, Dossiers ms. 3702 and 3721.

He also made numerous “squeezes”: imprints of hieroglyphic inscriptions and bas-reliefs with damp paper. And Du Camp was, in his term, “feverishly” involved with making photographs.4Souvenirs littéraires, vol.1 (Paris: Hachette, 1882-83), 424.

Gustave Flaubert, who accompanied him on this trip, referred to “Max’s photographic rages,” commenting “ I don’t know why Maxime hasn’t cracked up with this mania for photography.”5Letter to his mother, 15 April 1850 in Oeuvres complétes, vol.13 (Paris: Club de l’Honnête Homme, 1971-), 32.

These photographic efforts resulted in Egypte, Nubie, Palestine et Syrie, an elegant, large-sized volume containing 125 photographs and a lengthy introductory text. Published in 1852, this was the first French book to be illustrated with photographs, the first major photographic album on the Middle East, and one of the first significant photographically illustrated travel albums of any land.6Egypte, Nubie, Palestine et Syrie, dessins photographiques recueillis pendant les années 1849, 1850 et 1851 accompagnés d’un texte explicatif et précedés d’une introduction, par Maxime Du Camp (Paris: Gide et Baudry, 1852).

Given Du Camp’s prodigious efforts, his long and multifaceted involvement with the past as it was architecturally embodied, and the prominence of this publication (for which he, ambitious and young – not yet thirty – received the French Cross of the Legion of Honor), the actual photographs are a visual disappointment. They are dull, frontal, seemingly obligatory pictures of mosques, temples, and tombs. The one puzzling element that provides a curious relief from their general monotony is the repeated presence of the dark figure within the ancient ruins, often so placed as to be almost invisible. The use of a human figure to indicate architectural scale was a long established tradition, but the insistent solitude of Du Camp’s man and his odd, frequently hidden positionings are puzzling.

Considering only the photographs themselves, it might be possible to dismiss this peculiar presence as yet another example of the frustrating accidents of early photography, commented upon by several practitioners of the time. But while some of Du Camp’s pictorial results may be due to mere happenstance, when seen in the context of his writings related to his Egyptian project, their makeshift qualities take on a complex and problematic significance. His words hover around these Egyptian ruins speaking in a variety of voices: intimate and detached, arrogant and fearful, and constantly contradictory – contradictions already evident in the celebrated despair of “La Maison démolie.”

There is the lengthy, dry, scholarly introduction to the photographs themselves. The year after the album appeared Du Camp published Le Nil, a more informal, anecdotal travel journal without illustrations. In that same year of 1853 Du Camp also published a romantic, self-pitying, fictionalized autobiography set partly in Egypt called Le Livre posthume: mémoires d’un suicidé. Before his trip to Egypt, a ten-month trip in 1844 resulted in his youthful, opinionated Souvenirs et paysages d’Orient: Smyrne, Ephése, Magnesil, Constantinople, Scio, published in 1848. Later Du Camp nostalgically reconsidered both trips in Orient et Italie: souvenirs de voyage et de lectures published in 1868.7Le Nil (Paris: Librairie Nouvelle, 1855); subsequent citations in text indicated by N. Le Livre posthume: mémoires d’un suicidé, recuellis et publiés par Maxime Du Camp (Paris: V. Lecou, 1853); Citations in text indicated by LP Souvenirs et paysages d’Orient: Smyrne, Ephése, Magnesil, Constantinople, Scio (Paris: A Bertrand, 1848); Orient et Italie: souvenirs de voyage et de lectures (Paris: Didier, 1868). In addition, the prolific Du Camp wrote several short stories and poems which appeared shortly before and after his Egyptian trip and which address many of the themes of his travels among the maison démolies.

These writings, in their different guises, all reflect the conflicted feelings of the “Maison démolie,” the sense of loss and the exultant autonomy of the author while he obsessively records and memorializes the past from which he is apparently liberating himself.

The enigmatic figure photographed among the ruins flickers throughout the texts, like a protagonist in a film, somehow connected to the plot, but never fully developed and seen only in disconnected glimpses. He is not mentioned in the introduction to the photographs. That text was hastily patched together upon Du Camp’s return to Paris and is composed almost entirely of quotations of facts and measurements by two eminent archaeologists of his era, Champollion the Younger and Richard Lepsius. It contains few references of any sort to the photographs themselves.

Du Camp’s figure is first officially identified in the more anecdotal Le Nil. The reader is told:

“Each time I visited a monument I had my photographic apparatus carried along and took with me one of my sailors, Hadji-Ishmael, a very handsome Nubian, whom I had climb up on to the ruins which I wanted to photograph and in this way I was always able to include a uniform scale of proportions.”8N, 327. Although, in Le Nil and elsewhere, Du Camp identified only Hadji-Ishmael as his model, at times his “meaure of scale” was Flaubert and probably his Italian manservant Sassetti. Their assistance in photographing is mentioned, but they are never declared as being subjects in front of the camera.

This first textual reference takes place at Dendera, also the site of the first photograph of Hadji-Ishmael in the album and the closest view we are ever given of him (fig.4). Unlike most of the pictures, here we can clearly see Du Camp’s model, a dark-skinned man, clad in a loin-cloth and head-wrap, upright and frontal – kouros-like – standing in the portico of a small temple. Visually it seems the most commonplace picture of him. Textually, it is the only one to which Du Camp refers directly.

From Du Camp’s words, the reader is to understand this image as one of the loss of origins. The temple is described as having “no cartouche, no inscription to indicate the date of its construction nor the name of its founder.” Du Camp orders Hadji-Ishmael “to climb up on a column that bore the huge face of an idol,” an example, he writes, “of extreme degeneration,” an opinion borrowed from Champollion which he quotes in his introduction to the photographs as well as in Le Nil. In the same paragraph Du Camp moves to a description of an adjoining temple. “A birth temple, blackened, rifted, indecipherable, is half collapsed among the surrounding rubble. The ruins are now inhabited by owls who share their retreat with dun-colored jackals and big-eared bats” (N, 327).

In this first instance, the figure of Hadji-Ishmael fulfils Du Camp’s declared use of his model as a measure of scale, but even here, in the most straightforward of the pictures, the model is related to the architecture in ways that exceed his function as a staffage figure. His antecedents, anonymous if they were natives, were usually grouped or paired and, by means of this coupling device, were separated from their architectural surroundings. The solitariness and the authoring of Du Camp’s model effect a change in the relationship of the human being to the archaeological site: rather than being coupled with another person, Du Camp’s lone man is involved in a relationship to the site.

It is not a relationship in which he is looking at a monument as are some of the solitary figures one finds in prints and in other photographs. He is being observed as is the monument. He is not casually pausing, but posing, already an image to be looked at, even before the actual taking of the photograph.9See Craig Owens, “The Medusa Effect or, The Specular Ruse,” Art in America 72 (Jan.1984), 408. His pose is not the Westerner’s pervasive bent knee, foot-atop-base-of-monument that accents hundreds of travel images, but a more static one. Moreover, he is quasi-naked. This, coupled with his pose, signals (in Western terms) “backwardness,” associating him with this temple at Dendera, with its “degenerate” idol next to which he is ordered to pose, and with its oblivion.

In Le Nil Du Camp writes of Hadji-Ishmael only as “a very handsome Nubian,” not as the marker of degeneration or oblivion. But his unpublished travel notes are more ambivalent:

Hadji-Ishmael: of all the sailors he was the one I liked best. He was very sweet natured, with an ugly face, one-eyed, superb muscles. He posed perfectly: I always used him as a model, to establish the scale in my pictures. He jabbered a kind of gibberish that he had learned [from] a French businessman… he was rather slack and easily discouraged. He was a Nubian.10“Drogman, éqiupages de la cange,” Manuscrits et papiers inédits, Dossier ms. 3721. As translated in Francis Steegmuller, Flaubert in Egypt: A Sensibility on Tour (Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 1972), 225.

This description is full of contradictions. Hadji-Ishmael is “sweet natured,” but has an ugly face. He has “superb muscles,” but is one-eyed. He posed perfectly, but jabbered gibberish and was “slack” and “easily discouraged.” His main attribute is the docility with which he submits his body to Du Camp’s camera. In all that could demonstrate an intelligence separate from this purpose, the muscular Nubian is lacking. Hadji-Ishmael seems to be, for Du Camp, a corporeal part of the Egyptian maison démolie, rather than a sensient observer like himself. Hadji-Ishmael does not stand to one side, looking at the debris of his architectural past, but is a one-eyed, inarticulate, and obedient cipher of the ruins of his own cultural past.

According to the pragmatic terms of the French colonial project, of which the well-connected Du Camp (traveling with diplomatic passport and official instructions from the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles Lettres) was definitely a part, the documentation of such conditions of architectural degeneration and the obliviousness of the indigenous inhabitants to their own heritage illustrated the opportunity and need for French intervention in Egypt. It was to French advantage to understand Egypt as, in Du Camp’s words, a country “from which life is ebbing bit by bit, (N, 17)” and its Muslim faith as “waning, fading, dying.”11“La Mosquée turque,” Orient et Italie, 216.

There were a great number of Frenchmen attending to the national patient. Engineers, doctors, military men, scholars, teachers, writers, and artists were participating actively in the life of the country, founding hospitals and schools, building ports and factories, training the Egyptian army, unearthing monuments, deciphering hieroglyphics, making sketches, and importing numerous Egyptian artifacts to France. But Du Camp’s and his compatriots’ interest in Egypt at mid-nineteenth century far exceeded their pragmatic colonial investments. The French bourgeoisie, their material and moral values threatened by rapid industrial and social change, were uncertain about the direction – or even the continuation – of French civilization as they had known it. Du Camp departed Egypt a year after the 1848 French revolution, a political crisis that accentuated this prevailing and widespread uncertainty that had been gaining momentum since the turn of the century. Du Camp had played an active part in both the February and June 1848 insurrections as a member of the National Guard, the citizen militia which had been the mainstay of the July Monarchy, but which by 1848 had become dispirited and politically unsure.

For the upper middle class, torn between clinging to a past or being part of a new progressive technology, unsure whether to mourn or to celebrate the maison démolie, the Egyptian tombs and temples and their artifacts were a powerful symbol of an entire civilization on the brink of extinction. On the one hand, they played a major rhetorical role in a nineteenth-century historiography construed to restore contact with the origins of Western history and to reconstitute what was experienced as a fractured totality. Egypt, as the “Cradle of Western Civilization,” was crucial to a search for a heroic past in which Western man could find a guarantor of his future.

On the other hand, at mid-nineteenth century the past seemed a highly uncertain measure of the future. The shambles of contemporary Egypt so evident in Cairo, the toppled columns, destroyed statuary, illegible inscriptions of the ancient temples and tombs – a past continually vandalized in the present – all marked the specter of a glorious history at the edge of a total rupture from the present.12See my “The in visibility of Hadji-Ishamel,” 155-158, for the relationship of inscriptions and figures in Du Camp’s photographs.

Attitudes towards the Egyptian native were intricately bound to the anxieties involved in this Western enterprise of self-definition according to a genealogy of homeland. Implicit in one nineteenth-century notion of history was the sense of the progressive accumulation of human knowledge through the course of time and the consequent intellectual superiority of man at a later period in history to man at an earlier period. One form that this sense of superiority took in the era of European voyages of scientific exploration was the assumption that journeys to distant lands were journeys into the past, and consequently that the natives of these lands were in an earlier state of cultural development than the Europeans who studied them. Thus Théophile Gautier, in regard to the “Orient,” wrote of “unknown types, unpublished races.”13“Salon de 1857,” L’Artiste series 7, vol.1 (1857), 189.

This sense of cultural superiority rested on the fact that it was the Europeans who, equipped with advanced technological means, journeyed to other lands and made their occupants, as well as their artifacts, objects of scientific study, incorporating them into Western history as “discoveries.” In his short story “Reis Ibrahim,” Du Camp writes that he is bringing back “a curious animal”: the native.14Les Six aventures (Paris: Librairie Nouvelle, 1857), 15.

But the study of the native and the expropriation of the specimen “Other” whether in words or in flesh, was not without its ambiguities which resided in the discomforting illogic upon with the notion of Western superiority was based. The discontinuity in knowledge between the earlier and the later inhabitants of the same region undermined the concept of a progressive human development based on the gradual accumulation of knowledge throughout the course of history. The notion that the ancient Egyptians had achieved a high level of cultural and scientific development and that the contemporary native was naïve and ignorant implied that at some point there had been a break in the continuity of historical memory, a massive collective act of forgetting.15For this analysis I am indebted to John T. Irwin, American Hieroglyphics: The Symbol of the Egyptian Hieroglyphics in the American Renaissance (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1980); Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983), 174, ff.The stilling camera aimed at Hadji-Ishmael turned back onto the cameraman himself, threatening him with his own historical regression and oblivion. His position as outside onlooker of the maison démolie became increasingly difficult to maintain.

As the pictures in Du Camp’s album progress, the relationship of the model to the architecture becomes more diverse and complex. Often Hadji-Ishmael is literally framed by architecture and, in one instance, he has also been put on a pedestal like a statue (fig.5). In several photographs he inhabits the image as a dab of matter barnacled onto an ancient edifice, or as a shadow cast among other shadows at the tip of a temple. In many views his dark presence is indicated most readily, not by his body, but by the small, white triangle of his loincloth, a speck slightly more defined and regular than the hundreds of others forming the surrounding rubble.

When he is clearly distinguishable it is in the ways that associate his figure with those represented in the wall paintings and statuary of his ancestors. At times he is posed so as to assume the stiff position of a bas-relief as at Kardassy where he stands sideways, a dark outline pressed against the sky, delineated atop a monument such as the temple of Khons at Karnak, he seems a detached relief, one that has strayed from the walls to the summit, rather than an element external to the architecture. He is then not unlike Gautier’s description of native figures as “walking bands of colored bas-reliefs.”16L’Orient (Paris: Chapentier, 1877), 177.Whatever the variations, Hadji-Ishmael never assumes the cocky appropriating stance of Westerners at foreign sites.

Westerners, however, do assume a “native” stance. The construction of an alien alter ego through which to enact oneself was a common nineteenth-century literary trope, and by the 1850s the “Orient” in particular was established as the locus of cultural transvestism for the French. In Egypt, the French dressed in local costume and often assumed foreign names as did Du Camp. He became “Abu Muknaf,” the “Father of Thinness.” Flaubert, photographed by Du Camp in a long flowing robe, was known as “Abu Schenep,” the “Father of the Mustache.”

This Western identification with the native was, in one sense, part of the justification and even a glorification of the native’s “backward” condition. It was a fabrication of a “pure” native prompted by an overall nostalgia for origins and a suspicion of progress, one of the effects of the questioning of Western values in reaction to the industrial revolution. By mid-nineteenth century the “Oriental” had become less the barbarous villain of the Greek wars of the 1820s and more an embodiment of the virtues of natural man, opposed to the constrained, artificial European. By the time of Du Camp and Flaubert’s trip the identification was often with the native as, to use Flaubert’s words, “the child of the water, of the tropical sun, of the free life, full of distinction and nobility.”17Journal entry of 24 March 1850 in Voyages, vol.2 (Paris Société des Belles Lettres, 1948), 108. Trans. Steegmuller, Flaubert in Egypt, 133.

This romanticized attitude towards the “pure native” was not, however, a solution to the Westerner’s unresolved attitudes towards the past. If anything it added a disillusionment in progress to the threat of rupture, accentuating the ambiguities of a cultural identity already subject to self-doubt. In the context of a disillusionment in progress, the noble native posed a threat to the acculturated Western male. In short stories such as Du Camp’s “Reis Ibrahim,” the European male is found lacking “in the presence of this bronze Arab, simple, virtuous, primitive and superb in his ample robes.”18Les Six aventures, 21. Moreover, this idealization of the native turned the European into the corruptor of the past rather than its savior, an idea amply supported on a pragmatic level by French activity in Egypt. Contemporary accounts of the active participation of the French spoke of its degrading as well as it rehabilitating effects. The continual vandalization of monuments in the interest of study and financial gain and many other forms of destruction were subjects of alarm voiced by the French themselves. To take only one example, the corrupting influence of the French was often cited as the cause for the degeneration of what were considered the positive aspects of the Muslim religion (the solemnity of its celebrations and the disciplined devotions of its followers), often described by Du Camp and others as the other side of its fanaticism and violence. He writes that “European civilization in penetrating the Orient with its redingotes, drunkenness and percussion rifels, has singularly slackened the old Muslim rigidity.”19“La Mosquée turque,” 238.

Here, and in many other instances, Du Camp’s prose is noticeably sexualized. A female Orient is seen as prey to the impotent husband and a villainous interloper, as it were. Such a sexualization addressed the double threat posed by the native: the cultural and physical obliquity of Western man, and the shifting onto him of the responsibility for the destruction of a linear past. The penetration by the European is achieved, not by his prowess, but by means of the redingote (a garment that Du Camp sees as an example of a constraining, artificial Western culture, as opposed to the free “ample robes” of the native), and by drunkenness and rifles.

The local inhabitants, their traditions, and their architecture are all tightly imbricated within the commonly assumed metaphor of woman for nation. In Du Camp’s and others’ prose the disrepair of architecture forms a symbolic trope of a violated Orient. Writing of the mosque of Touloun, Du Camp describes “a masterpiece [that] has been shattered, broken, violated, dishonored” (N,48).

The personification of nations as woman was common, and the Orient in particular was defined by a network of sexual imagery which constituted it as female. By the early nineteenth century the fantasies that had been sparked by the eighteenth-century translation of the Thousand and One Nights into French had been tempered by a more informed, but nonetheless female image as the discoveries of archaeologists and philologists contributed to the created of an Orient as the birthplace of civilization, typically portrayed as the “mother.” Gérard de Nerval, writing of his 1842 trip in terms of a return to the mother’s breast, is an exemplary heir to this double-pronged tradition. But, according to a strand of Romantic personified historiography exemplified by Michelet, the passage of time was conceived as a process in which the youthful West attempts to extricate itself from the fatal embrace of the maternal Orient to attain the independence of manhood characterized as “order, form-giving, and rational.”20See Mary J. Harper, “Recovering the Other: Women and the Orient in Writings of Early Nineteenth-century France,” Critical Matrix, Princeton Working Papers in Women’s Studies 1, no.3 (1985). The potency of this symbolic correspondence was resolve somewhat incestuously by the Saint-Simonians (with whom Du Camp was in close contact in Cairo). Their voyage to the Orient took the form of a crusade to find the “Woman Messiah,” the Oriental “mother” who would join with the Western male “messiah” to found the new Golden Age, thus uniting a doctrine of social change by means of technology with a mystical sensualism.21See Harper, “Recovering the Other,” and Kari Weil’s essay in this volume.

By mid-century the already highly problematic historical project of joining the past (as Mother) to the present (as Western technocrat) was disease stricken. In his poem “Les Soeurs sanglantes” of 1855, Du Camp gives the identification of nation to female a morbid twist. “In my travels I saw Nations, they were women lying on their backs, moaning, bleeding, dying.”22Les Chants modernes, 115. Related to this metaphor are the last two lines of Du Camp’s description of the citadel of Cairo in Le Nil where he notes a menagerie in which only “a wheezy lion and two or three tired female hyenas pace sadly behind the bards of two cages” (N, 92).

In these lines one reads the metaphor of animals for the indigenous inhabitants of a land and, by extension, for the Orient itself: the fatigue of the nation as female and the impotence of her native sons. Du Camp’s would seem to be the discourse of the colonizer giving testimony of the imminent degeneration of the colonialized. But the extended metaphor of woman for the violated nation is part of the discourse of the colonialized as well, and in depreciating Western dress, rifles, and drunkenness, Du Camp over and over again puts himself on the side of the colonialized.

Hadji-Ishmael is an incarnation of such duplicities, as sexualized as his country, in imagery and in words. For example, there is the matter of his quasi-nakedness. This seems a natural way of signifying “native” and was not remarked upon in the review of Du Camp’s photographic album during this time or, with one exception,23See Elizabeth Anne McCauley, “The Photographic Adventure of Maxime Du Camp,” Library Chronicle of the University of Texas at Austin, 19 (1982):19-51.ours, yet a loincloth was not the usual native costume. Moreover, the native was never represented so scantily clothed unless it was appropriate to an occupation such as that of the shadouf worker, a member of a crew bucketing water from the Nile.

Hadji-Ishmael’s nakedness is one manifestation of the ambiguous double role he plays throughout Du Camp’s photographs. On the one hand it is a celebration of his native beauty and closeness to nature, on the other, his nakedness associates him – within the context of his culture – with those who did go naked. Apart from the shadouf workers, there were the young male snake charmers, who entered into the erotic of Western imagery and literature. Du Camp’s description in Le Nil is typical:

He undressed in front of me as proof that there would be no trickery. . . . The boy took the snake, wrapped it around his body, lifted it to his lips and let it glide several times between his shirt and his bare skin. He spit into its mouth, pressing his thumbs against the head of the innocent reptile, which immediately became as stiff and rigid as a rod. (N, 55-56).

Young unmarried Nubian women (and Hadji-Ishmael was a Nubian) also went semi-naked, typically clothed in only a short leather-fringed skirt, another source of excitement for the European imagination of the exotic and the erotic. The stripping of Hadji-Ishmael is then a rendering of him as “noble savage,” but, in the context of his culture, also as a lowly worked, an eroticized boy, and a young woman.

Some of these characterizations come together in the Livre posthume where Hadji-Ishmael, as the protagonist’s (Du Camp’s) servant, is portrayed as lusting for his master’s Egyptian concubine. There he is eventually given the jealous, scheming mistress. The discarded woman constitutes a locus of shared sexuality, but it is sharing resulting from the Western rejection of the Oriental female.

The first photograph of Hadji-Ishmael at Dendera (fig.4) also structures related sexual associations. The “degenerate” idol next to which Hadji-Ishmael was ordered to pose is Hathor, goddess of love and fertility. In a later photograph of the temple of Isis at Philae, Hadji-Ishmael is seated in a high crevice, his legs dangling down between those of an ancient pharaoh (fig.6), his living body in the present a humorous and questionable token of the generative powers of his past.

These ambiguous, culturally embedded ideas of a sexualized Orient acquired a particular coloration as they were located within the personal history of Du Camp, one such as to bring into high relief the doubts and conflicts prevalent in his culture. The lineage of Du Camp’s family was also on the brink of discontinuity. As an only child, he was, in face, the sole guarantor of its future. His father had died when he was barely a year old. Du Camp writes: “engendered by a dying man, I bore the weight of the blasphemous insolence of my father throughout my entire life.”24Le Livre posthume, 209. When he was fifteen his mother died: “that gentle ghost [who] haunted the years of my youth; it followed me on my travels, became a part of my intimate existence, my work, even my pleasures”.25Souvenirs littéraires, 1: 125. Just before his trip his grandmother died: “The last line of my direct family was broken.”26Ibid., 425.

In Livre posthume Du Camp explains the motivations for his trip in terms of paralyzing losses which “transformed [themselves] into a tyrannical passion.”

I became the measure of all things, I lived within myself, I appropriated the world without giving anything in return; all of the multiple impressions which awaited me every step of the way became the subjects of profound musings. (LP, 43)

The triumphant, autonomous “palace2 of the heart of “La Maison démolie” had become a prison and the demolished room where “the image of my mother was suspended nearby” returned with a vengeance in what is perhaps the most striking passage of the Livre posthume It tells of a dream Du Camp, in his journals, claims to have had on May 25, 1850, the very place and time of the opening chapter of the novel. In his dream Du Camp learns that the mother he had believed dead for thirteen years still lives. She is described as “continually dying of the same illness,” hidden away in a room which has yellow stucco walls with rows of green turbans hanging from the cornices. At the four corners are suspended bloody heads of negroes. The mother is twice metamorphosed: first into a young Turk wearing a green redingcote who prostrates himself on the ground in prayer. In the final scene she becomes a hyena, a beast whose “voice can be heard all the way from the Sahara to the Place des Victoires,” and who feeds exclusively on corpses, and understands only native dialect. “I’m hungry,” she says, “they do not feed me.” The dream ends as the hyena-mother lunges forward through the bars of her cage, biting off her son’s outstretched fist with her powerful jaws (LP, 282).

The links to the mother “suspended” in “La Maison démolie” and to Du Camp’s descriptions of Egypt are so obvious as to be almost overly contrived. A decorative element of the pasha’s mosque in Cairo, described by Du Camp in Le Nil, is its gilded molding topped by rows of turbans. The hanging of actual decapitated heads (as opposed to symbolic turbans) in public places was a common fate for those executed in Egypt and is described by Du Camp. The redingcote, worn by the mother-as-Turk in he dream is one of the European imports singled out by Du Camp as a factor that has caused “the slackening of ancient Muslim rigor.” This further situates any emasculation of the Oriental male as taking place within the fatal bonds of the Oriental mother, and effected by the sins of Western man. A “wheezy lion” and “tired female hyenas” conclude Du Camp’s description of the citadel in Le Nil. A whole Egypt is described in Le Nil as “a dying country from which life is ebbing bit by bit,” as much as the mother in the dream is “continually dying of the same illness.”

In writing of death as a recurring process rather than as a final closure, Du Camp is in keeping with a Romantic literary tradition. The outraged relish of his eroticised prose is yet another aspect of this tradition, continually reanimating the destruction he both desires and fears. It was in the maision démolie – “shattered, broken, violated, dishonored,” as was the mosque and the faith it symbolized – that Du Camp “swa the uncertain future released” and heard “the tumultuous swarm of erased dreams.” It was through the destruction of this longed-for space of the woman’s body that a future, however uncertain, could be released, that dreams could finally be erased. Paradoxically, it was a release Du Camp sought in the very demolition against which he raged.

Du Camp’s position within such a paradox is enacted by the presence of Hadji-Ishmael among the ruins. It is in the very terms of a staffage figure that Du Camp describes himself in the Livre posthume: “I became the measure of all things” (LP, 43). But Du Camp’s association with his measure of scale went further than allegorical fantasy. Through the Saint-Simonians he had become a believer in reincarnation, his own continual death and rebirth. Not only did he write:

I was born a traveler, active and lean;

My feet are curved and parched like a Bedouin’s;

My hair is frizzy like that of a negro,

And my eyes undaunted by any sun.27“Avatars,” Les Chants modernes, 229.

but also, “ the delicious sensation that pervaded me every time I . . . journeyed towards the unknown like a hadji in search of an ideal Mecca; was that not perhaps the unconscious happiness of a return to the life of my ancestors?”28Souvenirs littéraires, 1: 479.

The device of a double standing in for the self is a literary trope that Du Camp, self-proclaimed heir of a Romantic tradition, uses again and again in his novels, short stories, and poems. It is not surprising that, at some level of consciousness, he should carry such a device over to his photographic activity. Moreover, in Freudian terms, Du Camp’s use of Hadji-Ishmael as a double “other” parallels both the historical and personal projects that constituted the voyage en Orient as a return to ancestors, to the origins of civilization, and to the breast of the Mother of the Western World. According to Freud, the use of the double in the structuring of anxiety is originally an insurance against the destruction of the ego, a denial of the power of death. It can be read as a regression to a primitive childhood state in which the ego is not yet sharply differentiated from the external world and from other persons. However, still keeping to Freud’s reading, when the primitive childhood state is left behind, the double becomes a harbinger of death, and it was, in fact, as such that it was so often conceived in Romantic prose and verse.

As in the work of many Romantics, Du Camp’s is never a simple appropriation, an either/or in which the double acts as an insuring agent or a threatening one. The relationship between author and authored, the self as subject and as object, is a continually oscillating one, much like the mimeticising creature that determines its camouflage but is also determined by the nature of its disguise, often destroyed because of the very protective aspects it has assumed.29See Roger Caillois, “Mimicry and Legendary Psychasthenia,” and Denis Hollier, “Mimesis and Castration 1937,” October 31 (Winter 1984), 3-15; 17-32.

It is this play between subjecthood and objecthood, evident throughout Du Camp’s writing, that can be considered at the core of the photographic act in which Du Camp was so “feverishly” engaged. It is one that constitutes photography’s particular dance of death, its “micro-version of parenthesis,” in Roland Barthes’s words.30Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography trans. Richard Howard (New York: Hill and Wang, 1977), 14. The subject in front of the camera during that subtle moment of being photographed is “neither subject nor object but a subject who feels he is becoming an object.” He becomes, to continue Barthes’s words,

The target, the referent, a kind of little simulacrum. . . the Spectrum of the photograph, because this word retains, through its root, a relation to spectacle and adds to it that rather terrible thing which is there in every photograph: the return of the dead. (9)

Du Camp induced Hadji-Ishmael’s two-minute stillness in front of his camera by means of a ruse which he describes in Le Nil.

The great difficulty was to get Hadji-Ishmael to stand perfectly motionless while I performed my operations; and I finally succeeded by means of a trick. . . I told him that the brass tube of the lens jutting from the camera was a cannon, which would vomit a hail of shot if he had the misfortune to move – a story which immobilized him completely, as can be seen from my plates.31N, 327. As translated by Steegmuller, Flaubert in Egypt, 101.

Du Camp was not inventing a tale: any movement of Hadji-Ishmael’s would indeed have resulted in a ghostly chemical disappearance of corporeality, producing those wisps of disintegrating bodies that haunt Egyptian scenes photographed by other early photographers. This, of course, Du Camp well knew. The shadow-play through which Du Camp repeatedly stilled the figure of Hadji-Ishmael in the nooks, crannies, and summits of Egyptian ruins, regarding him from under his camera’s “black veil” with the threat of death, can be considered enactments of death and thus repeated deferments of death. His was a protection of life through “an economy of death,”32See Jacques Derrida, “Freud and the Scene of Writing,” Writing and Difference trans. Alan Bass (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1978), 202. a defense through repetition and reserve.

It was in many ways the mid-nineteenth century status of photography as a rational, disinterested form of ordering that allowed for such a play of the irreconcilable. The mythic proportions of realism claimed for the photograph were indispensable for the maintenance of Du Camp’s pretensions, providing a smokescreen of objectivity which declared one project while simultaneously carrying out another. The illusion of disinterested banality was heightened by Du Camp’s direct frontal stance from a middle terrain, his distance from his subjects, and his positioning of the monument in the central ground. The photographs are testimony to his statement that he brought along a camera only because “he needed an instrument of precision in order to bring back images which would allow me exact reconstructions.”33Souvenirs littéraires, 1: 269. Photography provided Du Camp with a provision of reassurance implicit in any scenario that structures anxiety. Using a medium considered incapable of imaginative creation, Du Camp’s neutral, frontal stance further minimized the recognition of his stance as the photographer, structuring a denial of the object’s presence in his individual space and time. In a poem of 1855 Du Camp took on the voice of photography itself asserting that, “Drawings a man would not attempt / Are, for me, always docile; / I need but look upon them.”34“La Vapeur”, Les Chants modernes, 269. 4]

As a photographer, and not the camera itself, the docility of his subjects was, in actuality always ambivalent. Like many of his contemporaries, Du Camp’s prodigious recording activities were never wholly directors towards reconstituting a fractured totality. They continually functioned in the fullness of their enactments and reenactments of loss.

At the end of his journey in Beirut, Maxime Du Camp exchanged all of his meticulously assembled photographic equipment for ten feet of embroidered materials intended towards the creation of a large Oriental bed to take home to Paris.35See Flaubert’s letter to his mother, 7 October 1850 in Oeuvres complétes, vol.13, 87.

This essay by Julia Ballerini was originally published in Home and its Dislocations in Nineteenth-Century France, edited by Suzanne Nash, published by State University of New York Press in 1993.