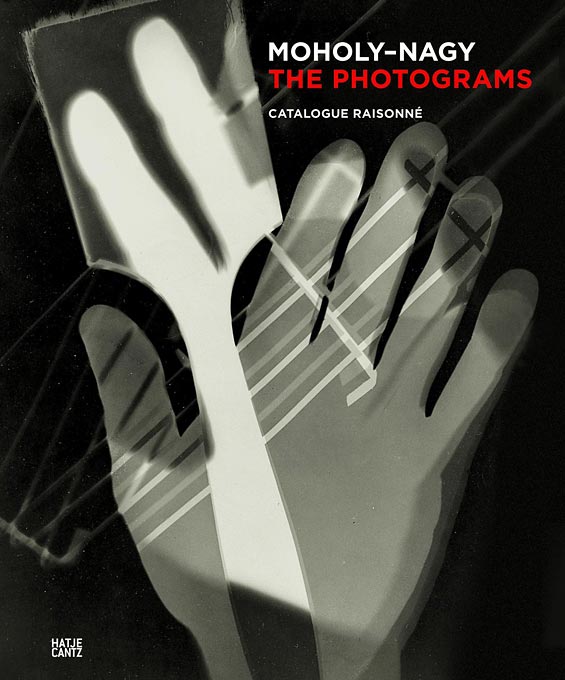

In 2009, Hatje Cantz published a catalogue raisonné of László Moholy-Nagy’s photograms – the first book to feature all of Moholy-Nagy’s nearly 450 known photograms in chronological order. “I learned a lot about the production of photograms from Renate Heyne and Floris Neusüss, the compilers of the catalogue raisonné,” Hattula Moholy-Nagy told The Classic in our Spring 2021 issue. “It was an excellent experience. I also became more aware of how Moholy-Nagy’s artistic vision carried over from one medium to others at any given time and how he developed a style particular to photograms.” As an extension of our interview with Hattula Moholy-Nagy, we asked Renate Heyne a few questions about Moholy-Nagy’s process, starting with one photogram in particular.

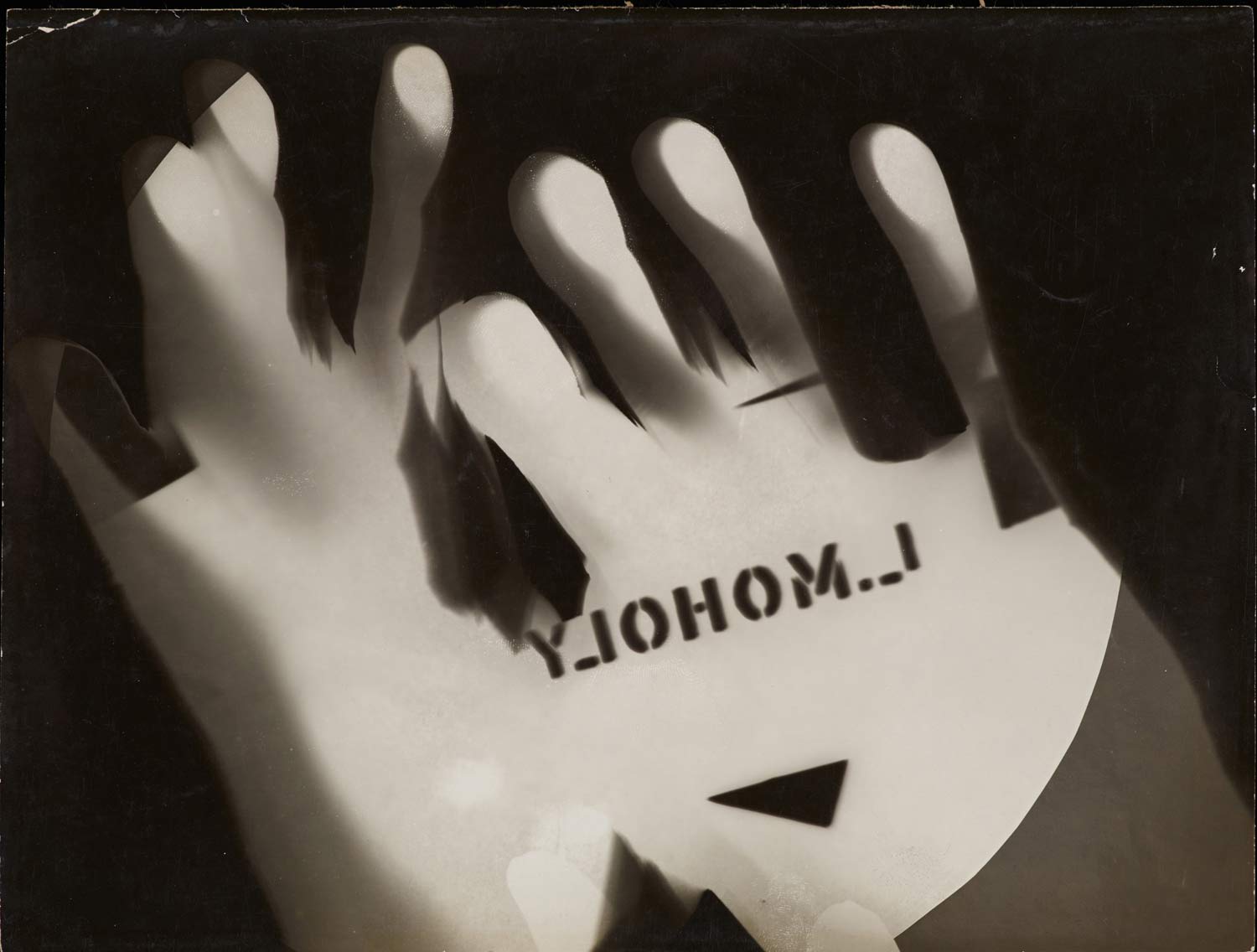

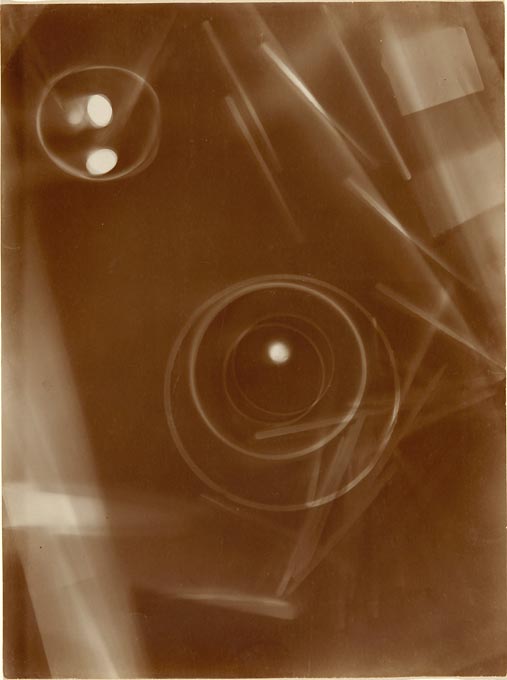

The Classic: This photogram was made in the mid-1920s, at which point Moholy-Nagy would have been at the Bauhaus in Dessau. Would you describe this photogram as typical of those produced at this time? What are some of the hallmarks of his early photogram process?

Renate Heyne: It may be “typical” for Moholy’s photograms that individual pieces cannot be described as “typical” in any respect. Like a painter, with every photogram he enters a new realm even when pictorial elements like hands are used repeatedly.

One may try a general approach towards Moholy’s photograms (especially from the Dessau period) in contrast to those by Man Ray: there is Moholy trying to shape light with non-recognisable objects and there is Man Ray whose recognisable objects are shaped by light.

TC: Based on your research, how do you imagine he created this work, in a technical sense? Is there anything particularly unique about Moholy-Nagy adding his name to this image?

RH: Technically this looks like two exposures (with the light source from two directions) of hands and a spherical shape – and a third exposure of a template with stenciled letters (or these were exposed first). With his name added this image says “I, Moholy, am shaping light with my hands” or “I grasp the light”. The image kind of describes Moholy as “The Maker of Photograms” or “The Master of Photograms” even.

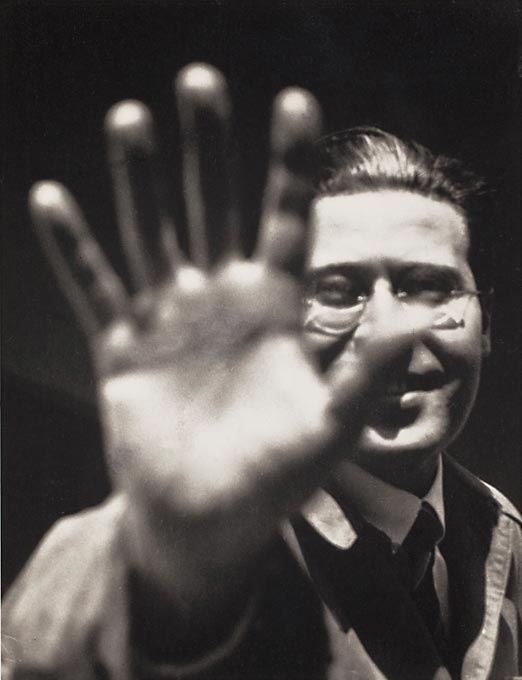

TC: Body parts (hands, noses, lips) appear to function as a motif in a number of Moholy-Nagy’s photograms. Why do you think that is?

RH: Portraits are a classical subject in painting as well as in photography so why not try in photograms? A head neatly fits in a 24 x 18 cm sheet of photographic paper and hands as well.

There is probably no photogram maker who didn’t use his hands as subject – mostly at the beginning of his practice. For Moholy it meant a personal identification with a pictorial technique that offered him the possibility to replace pigment with light.

TC: I thought this photogram was interesting to discuss in light of part of your Catalogue Raisonné essay, in which you write: “…while in some series one can sense Moholy-Nagy’s intervening hand, in others he himself remains entirely passive, as though waiting for the material to show what it can do by itself.” In this photogram, we have (his?) actual hands intervening – what might you make of his intention here?

RH: Handling light actively. It seems Moholy felt an almost ecstatic relation to light.

TC: Along with Hattula Moholy-Nagy and Floris Neusüss, your work was instrumental in the 2009 publication of Moholy-Nagy. The Photograms. Catalogue Raisonné. How did you come to be involved in this project?

RH: The history of the photogram in the arts of the 20th century (with a brief review of the photogram’s invention in the 19th century) had been a subject Floris and I treated during the 1980s and it resulted in a comprehensive book which came out in 1990. After that we began to focus on the photogram work of individual artists from the early 20th century. During these researches we received particularly encouraging support from Hattula Moholy-Nagy which led us to the idea of working towards a catalogue raisonné of his photograms.

TC: There are over 400 photograms presented in the Catalogue Raisonné. What goals did you set out to accomplish at the outset of your research, and did those goals change along the way?

RH: In the first place, the cat. rais. should be as complete as possible, of course. This meant that we browsed books, magazines, journals, catalogues and many kinds of printed matter to detect published photograms by Moholy-Nagy. Secondly, it was our goal to view “in the flesh” as many of his photograms as possible. So we continued, as we had already done for the above mentioned book, with a lot of traveling. We visited collectors, auction houses, galleries and museums in order to study their original photograms by Moholy-Nagy and we asked them for reproductions. After we had seen as many originals as possible it was a very challenging task to establish a chronology, because in most cases Moholy didn’t date his photograms (nor sign them). In our studio we set up long rows of tables and for weeks we arranged and re-arranged the 421 reproductions until we were satisfied with the order. Even art historians today are not particularly familiar with photograms. Therefore we wanted to feed the cat. rais. with as much additional informations as possible in order to communicate an understanding of the photogram technique with regard to Moholy’s goals, working methods and strategies. So we didn’t show a photogram together with only its technical description. Particular aspects of this oeuvre, like Moholy’s “revaluations” (reversing the tonalities) of photograms, his attempt to use photograms in advertising, the relation of his photograms with his “light space modulator”, enlargements of photograms, exhibition practice, photogram editions, teaching photograms, exploration of photographic materials he would use – all are discussed in this book as well, interrupting the flow of the 421 photograms.

TC: What were some of the most surprising discoveries you made about Moholy-Nagy’s photogram process?

RH: There were quite a few, but maybe most surprising was our discovery of the photograms that triggered Moholy’s own beginning of photogram practice in autumn of 1922. At that time he was a novice to photography and he had no technical knowledge about processing images. There had been some reasoning among artists around 1926 about who was the first one to have “discovered” the photogram technique (among artists in 1926, photography’s 19th-century history was not as well known as today) and rumors said that Lissitzky had accused Moholy of having stolen the idea for photograms from Man Ray, in 1922. Moholy in his defence named “a woman from Loheland” as his source. For years we were unsuccessful in locating this woman and a place called “Loheland” at all because at this time of our researches there was no internet. One evening early in the 1990’s we had a family as dinner guests. Not long after our meal the father, who was a pastor, excused himself for having to leave already because early the next morning he would have to attend a meeting in Loheland… Soon, together with Herbert Molderings, we traveled to Loheland, located in the Rhön mountains in Hesse. Today it is a Waldorf school, and in their archives we became acquainted with a set of small and delicate photograms of blossoms and petals on daylight printing-out-paper, made between 1920-22 by Bertha Günther, obviously the “woman from Loheland”. In the summer of 1922 Moholy and his wife Lucia had spent their summer vacations nearby and visited the Loheland school, where photographic practice took place in a darkroom located in a discarded railway carriage. Discussing Bertha Günther’s photograms, Herbert Molderings in our cat. rais. shines light on another and widely neglected history of the photogram which happened in amateur practice. Under the label of “photographic amusements” or “photographic pastimes” photographic amateurs published their often playful experiments in various books and magazines. Most probably Bertha Günther had received her impetus from these sources.

Renate Heyne studied at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf with Joseph Beuys; in collaboration as partner with Floris Neusüss since ca. 1970.