Since the publication in 2013 of the last of my 3-volume History of Photography in China,1Terry Bennett, History of Photography in China 1842-1860 (London: Quaritch, 2009); Terry Bennett, History of Photography in China Western Photographers 1861-1879 (London: Quaritch, 2010); Terry Bennett, History of Photography in China Chinese Photographers 1844-1879 (London: Quaritch, 2013) there have been many new discoveries and research findings that some readers of The Classic Platform might find interesting. I have chosen some examples but have unfortunately had to restrict the number due to space constraints.

In the last few years, there has been something of an explosion in books and articles on Chinese photo history – especially in China. It’s now becoming almost impossible to keep track of them all, and I look back with nostalgia when I first started to research the subject some 15 years ago. At that time, it was just possible to feel confident about covering most of the available sources. The task today, however, is truly daunting.

JULES ITIER

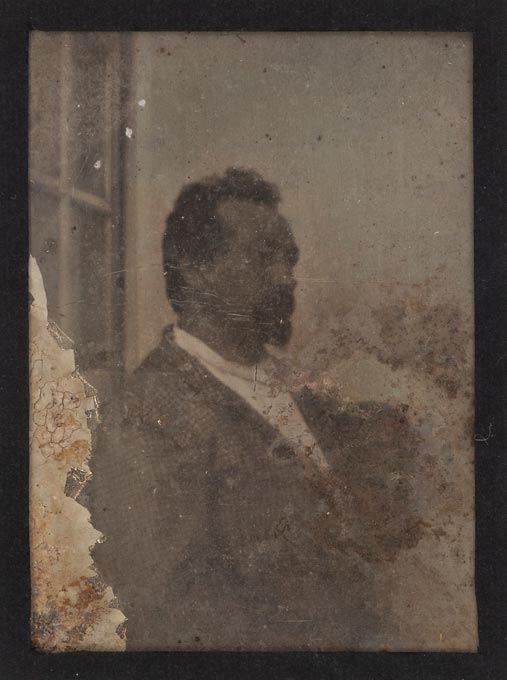

I start with the creator of the oldest surviving photographs of China – the French customs inspector and amateur daguerreotypist, Jules Itier (1802-1877).

In 1843, Itier was appointed chief of a commercial mission to China, the East Indies and the Pacific islands, reporting to the ambassador, Théodore de Lagrené. The French wanted to secure at least equivalent terms to those secured with China by Great Britain in the 1842 Nanking (Nanjing) Treaty. Itier arrived in China in 1844, and before the end of the year, he was taking daguerreotypes in Canton (Guangzhou), Macau and Whampoa (Huangpu).

More than 40 of these daguerreotypes have survived. The vast majority are with the Musée français de la photographie at Bièvres, and the remaining handful are with various private collections, including my own. The daguerreotypes were discovered in the 1970s in the photographer’s former family home at Véras, southern France, by collector Gilbert Gimon. In 1980/81, Gimon published two articles setting out the results of his research on Itier. It then appears that he began to dispose of the plates. By the time of his death, it seems that only six daguerreotypes were left with the Gimon family. These were subsequently auctioned at the Galerie de Chartres on 25 May 2019. Although all of them were quite faded, the best of the group was a view of a pagoda in Guangzhou, acquired by a French dealer. I was pleased to secure the others, including the Itier self-portrait shown here. The second view is very badly faded. We can only just make out one French official and the outlines of two seated individuals – at least one of which is Chinese.2Early articles on Itier’s work: Gilbert Gimon, ‘Jules Itier,’ Prestige de la Photographie, 9, April 1980, pp. 6–31; Gilbert Gimon, ‘Jules Itier, Daguerreotypist,’ History of Photography, 3, July 1981, pp. 225–44. Recent articles: Gilles Massot ‘Jules Itier and the Lagrené Mission’, History of Photography, (2015) 39:4, 319-347; Barbara Staniszewska, ‘Jules Itier (1802-1877) A French Daguerreotypist in Macao’, Estudos De Macau, (2015, pp.42-54)

NATALIS RONDOT

Still staying with the Lagrené Mission, a significant discovery was made just a few years ago in France. A dealer offered a group of 9 quarter-plate unmounted daguerreotypes, which included several Chinese scenes and portraits. The consensus amongst the experts and dealers who saw them was that they dated from the 1840s. There didn’t seem to be any obvious link to Jules Itier, but of course, he had to remain a candidate for authorship.

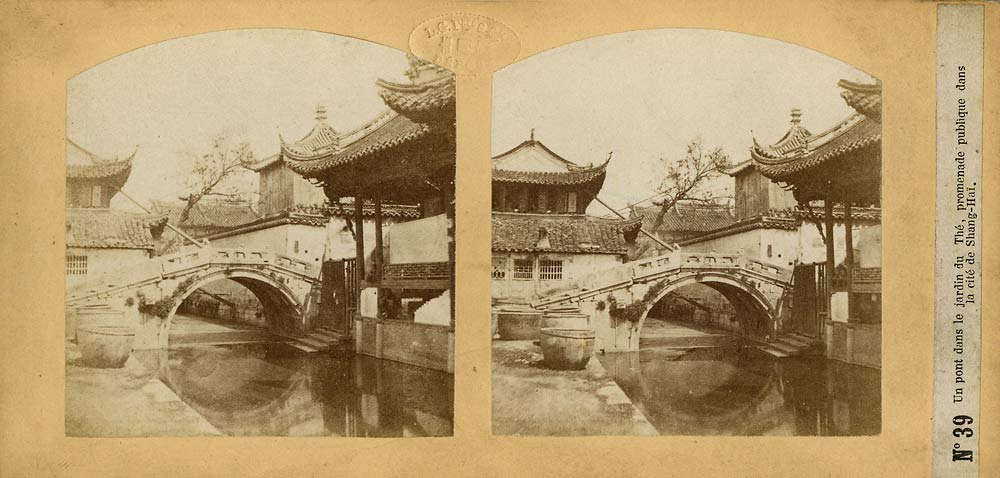

Collector and dealer Serge Kakou then discovered that one of the plates was of the famous tea garden in Shanghai (Yuyuan). He had matched it with an 1850s stereoview of the same scene. The Lagrené Mission had gone on to Shanghai. Meantime, Jules Itier had become ill in November 1844 and stayed in Guangzhou to recuperate while the French mission continued without him to northern China. Onboard was the historian and economist Natalis Rondot (1821-1900), who had already used the mission’s official daguerreotype equipment. One of the nine plates was a portrait of a Westerner who bears some resemblance to a picture of Rondot taken in later life.

The Shanghai plate of the Yuyuan is the earliest-known photograph taken in Shanghai. Although we can’t be sure, the author of this group of daguerreotypes is likely to be Rondot.

A 1902 biography referred to Rondot’s maintenance, whilst in China, of 4 manuscript volumes of 500 pages each; these have yet to resurface. If and when they appear, we may get the definitive answer.

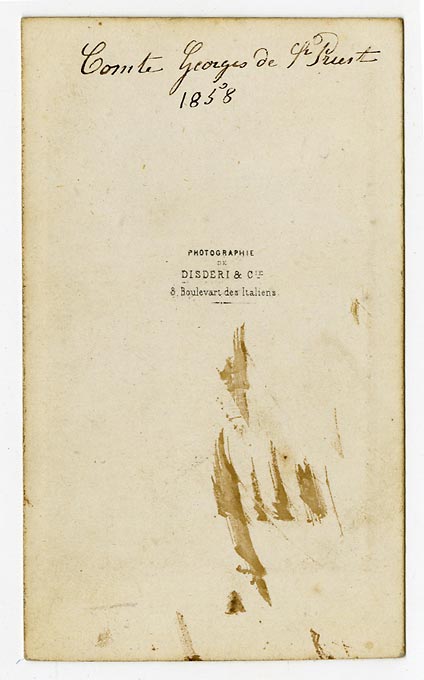

GEORGES DE SAINT-PRIEST

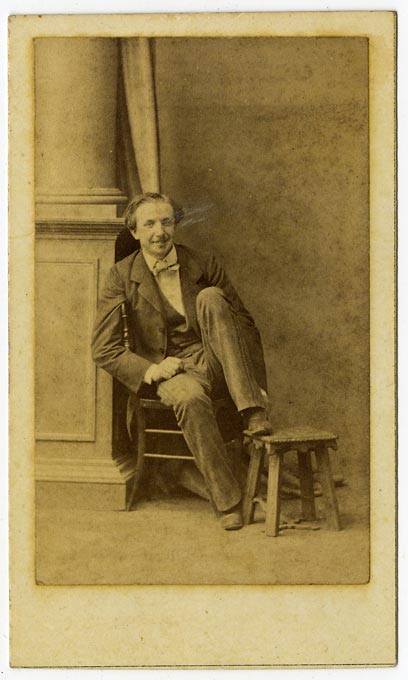

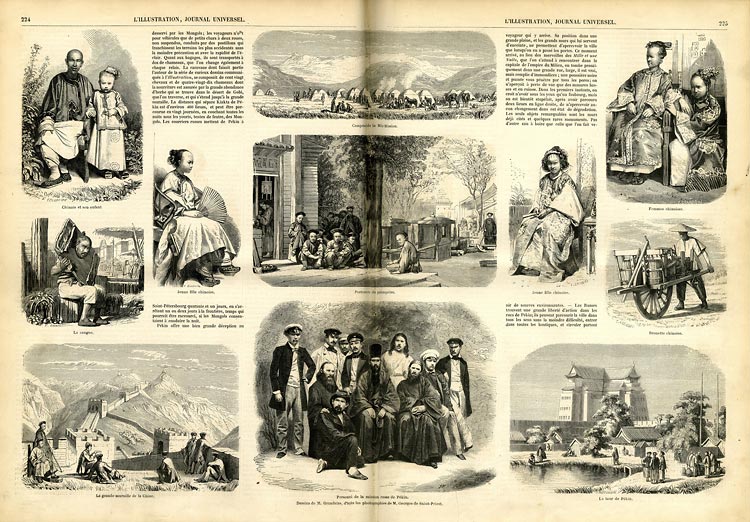

In the first volume of my History of Photography in China, I mentioned that Felice Beato was not the first to take photographs in Beijing after arriving there in October 1860. The evidence for this is shown in the 29 September 1860 issue of the French periodical L’Illustration where a group of 11 engravings after photographs by Georges de Saint-Priest (1835-1898) were included. The accompanying article was short on detail. The aristocrat Saint-Priest had Russian family connections and travelled to Beijing on a visit to the Russian Ecclesiastical Mission established there since the 18th century. They were the only foreigners allowed to live in the capital, and presumably, Saint-Priest was posing as a Russian. Very little is known about Saint-Priest, and I was pleased to recently find a Disderi & Co. carte de visite portrait of the Frenchman, dated 1858.

Although it is clear that Saint-Priest used his camera in the capital before Beato, the article in L’Illustration did not make clear when that was. Nor did it state the purpose of his visit or the exact route Saint-Priest followed to get there. It was oddly vague.

A couple of years ago, I came across an article published in the Shanghai newspaper North China Herald, 30 July 1859 (p.5). It was in the form of a letter to the editor, with the heading: A Journey from St. Petersburgh to Peking. The writer does not give his name but signs off as ‘A French Traveller. Astor House, Shanghai, July 20th, 1859.’ The article is quite long and gives some idea – though sketchy – of the route taken to Beijing and back. The writer does not provide the purpose of his visit and does not discuss what he did in the capital. The writer is undoubtedly Saint-Priest. It seems that he arrived in Beijing in February 1859. Why is this article – and the one in L’Illustration – so vague? My theory is that he was a spy sent by the French to bring back valuable information to the military ahead of the planned allied invasion, which took place the following year.

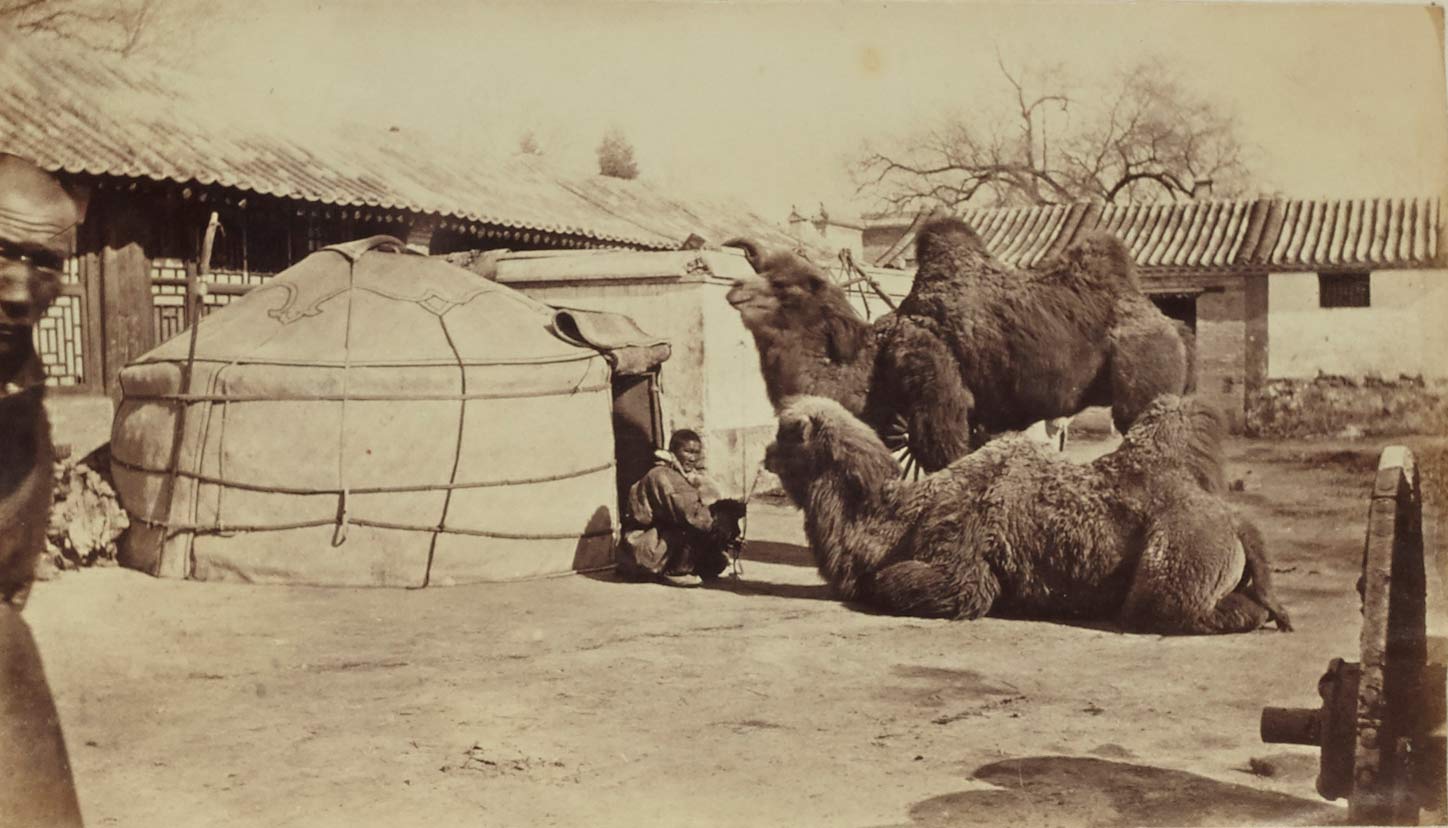

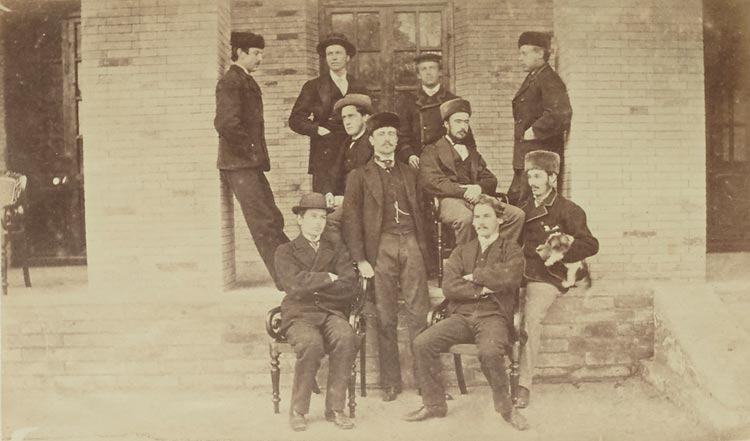

Incidentally, I think it most likely that the Russians at the Ecclesiastical Mission, who included scientists and artists, took photographs perhaps some years before Saint-Priest used his camera. The bearded Russian artist, Lev Stepanovich Igorev (1822–1893), is seated at the front of the group in the engraving illustrated here. It is very likely that he is the photographer of a group of forty-three photographs in the London Missionary Society archives (SOAS, Library, archives, CWM/LMS/15/10/5/079). I hope that evidence of this kind of early Russian photography in Beijing will surface from Russian archives.

RICHARD SHANNON

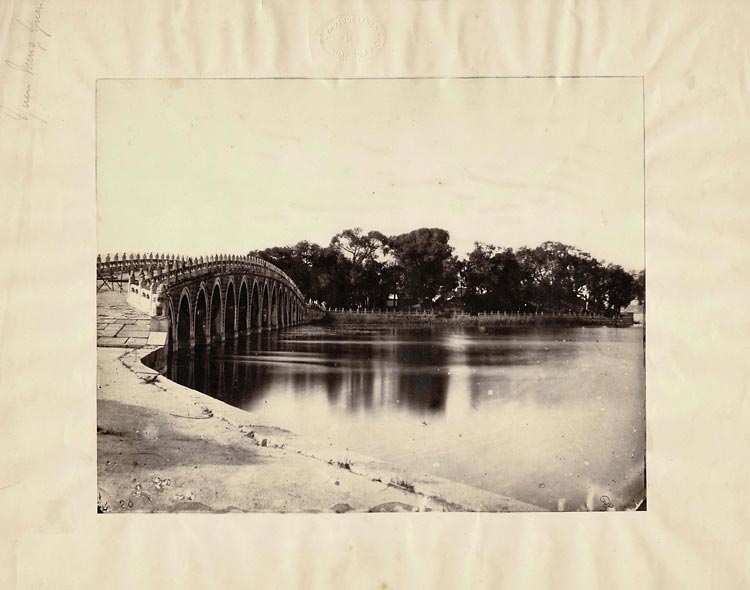

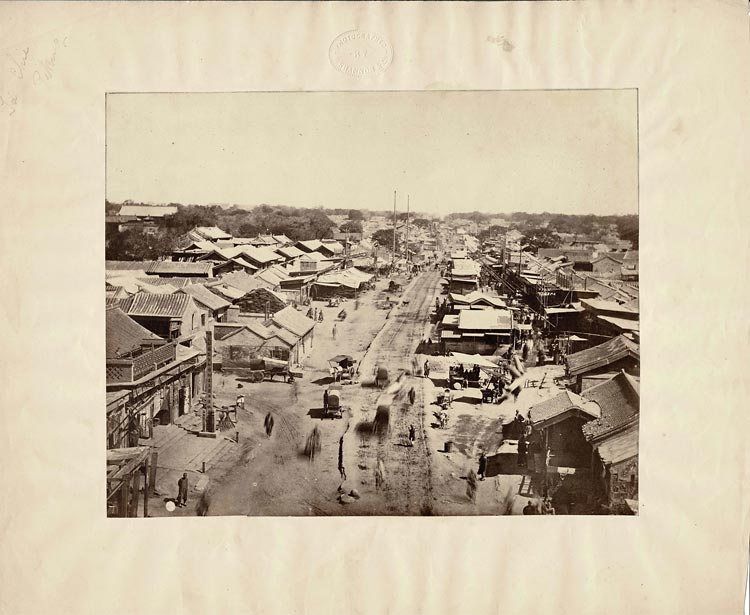

In January 1863, Richard Shannon (c.1829-1871) opened one of the first studios in Shanghai. His first advertisement offered images of Beijing, which would have been amongst the first available in Shanghai. However, until recently, it had not been possible to identify any examples of his work.

There is a rare – but not impossible to find – superb series of Beijing topographical images from the early 1860s, with what appear to be the photographer’s difficult-to-read initials shown in the negative. A few years ago, Serge Kakou told me that he thought they could be read as ‘RS’ and that the prime candidate was Shannon. It turned out he was right. Recently I was offered a group of 11 views from the series, each mount carrying the studio blind-stamp: ‘Photographed By R. Shannon & Co’.

1863 January 24 (The Daily Shipping and Commercial Advertiser)

PHOTOGRAPHY

Now publishing a series of views from PEKING, YUEN MING YUEN, the MING TOMBS and the GREAT WALL. Photographed from nature by RD. Shannon. Specimens may be seen at the Photographic Studio, Canton Road. Where all orders will be punctually attended to. RD. SHANNON & CO. PHOTOGRAPHERS

Shanghai 17th January 1863.

CHARLES WEED

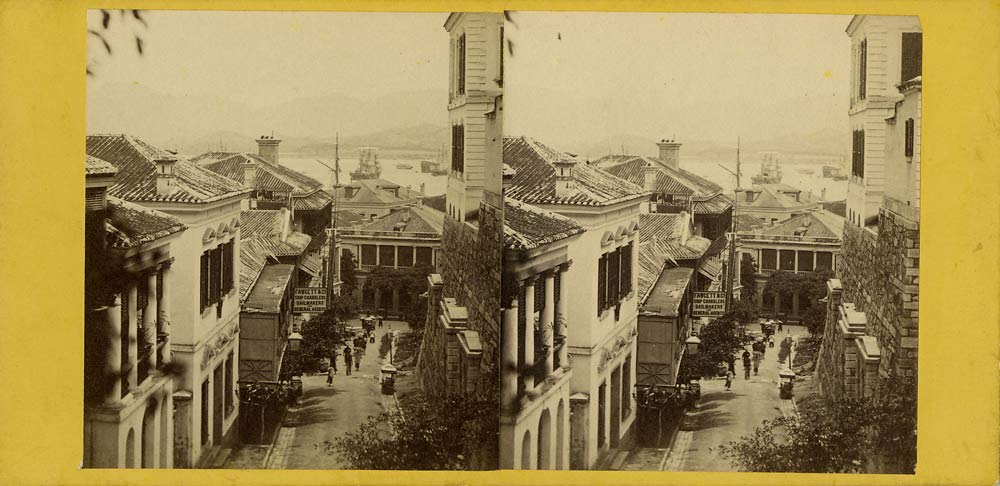

Operating a studio in Hong Kong from February 1860, Charles Leander Weed (1824-1903) was one of the early commercial practitioners in China. He had already been successful in San Francisco, where he was a partner in the celebrated Robert Vance studio. Later in 1860, Weed moved on to Canton and Shanghai, where he set up temporary studios. In September 1861, he left China to return to California. He returned to Hong Kong in 1866 and ran studios there and in Shanghai for four years.

As far as I know, attempts to identify Weed’s work from his first trip (1860-61) have not been successful; a few mammoth-plate views from his 1866-1870 stay are known, but very little of his other work has been uncovered. When he left China the second time, never to return, he passed his business on to a fellow American, Lorenzo Fisler, and the bulk of his negatives may have been dispersed at the same time.

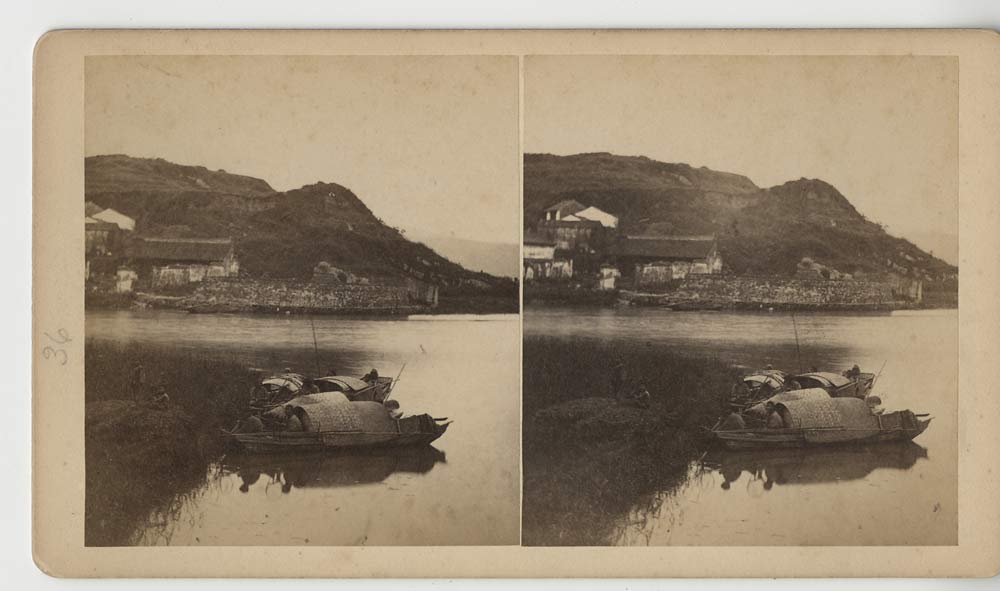

However, in the late-1860s, a Thomas Houseworth catalogue listed a series of China and Japan stereos photographed by Weed. A few years ago, I was delighted to acquire a group of these, but whether they were taken by Weed during his first or second trip is not yet clear.

CHARLES FREDERICK MOORE

Just two years ago, a significant discovery was made by Jamie Carstairs – manager of the Historical Photographs of China project and an expert in photography in China. Jamie is fortunate in that he has seen tens of thousands of China photographs during the course of his work. Whilst working recently with the Royal BC Museum in Canada, identifying buildings and locations in 99 glass plate negatives by Charles Frederick Moore (1837-1916), Jamie noticed some surprising matches to known images attributed to other photographers.

Following further research, Jamie concluded that many existing attributions to photographers such as John Dudgeon and Théophile Piry need to be revisited. Moore and his work are therefore of some considerable importance. It is clear that he was an active photographer in China during the 1870s & 1880s. Still, given that he was in China from the early 1860s, serving with General Gordon in fighting the Taiping rebels, earlier work may emerge. Jamie’s important notes can be found here: https://hpchina.blogs.bristol.ac.uk/2019/12/05/charles-frederick-moore-1837-1916-a-photographer-in-china/

GEORGES MORACHE

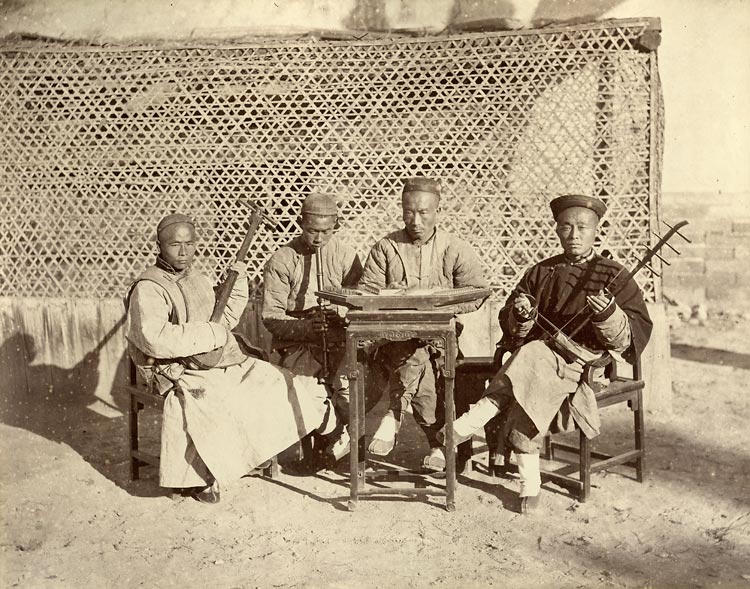

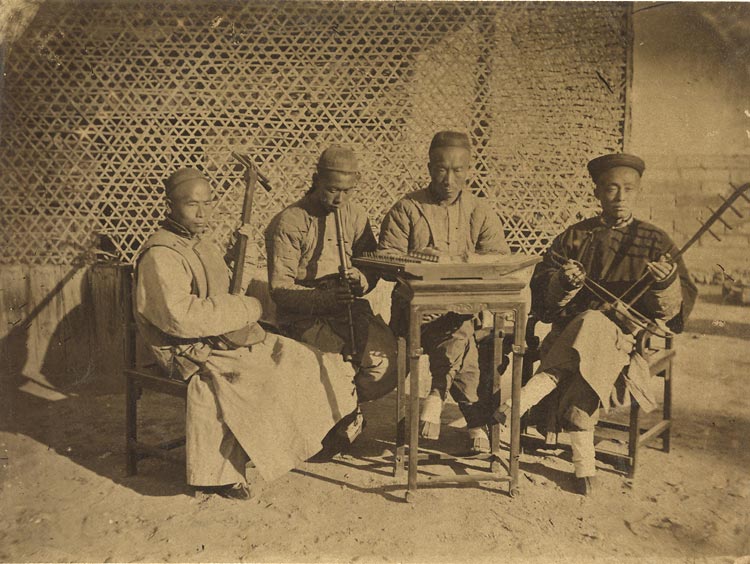

When coming across a close variant of a known image, the reflex temptation attributes both photographs to the same artist. However, at least in the context of early photography in China, there is a mounting body of evidence that shows that two or more photographers would often work together, each using their cameras to capture the same portrait or view.

China in the 19th century was not an easy place for foreigners to travel with and use their cameras. Reports show that reactions from the native Chinese were unpredictable and ranged from curiosity to downright hostility. Photographers would often feel uncomfortable or threatened when surrounded by large crowds. Resident photographers, however, would be better placed to deal with such situations. They would also know the best places to photograph and how to get there efficiently and safely. Therefore, a photographer visiting Shanghai or Beijing for the first time might well seek out their company when planning a photography excursion.

I have come across several references to this kind of activity. For example, Shanghai-based commercial photographers William Saunders and Harrison Dinmore – despite operating competing studios – travelled to Beijing together in 1866 and brought back separate portfolios. When visiting Beijing in 1871, John Thomson sought out and benefited from the support of fellow Scotsman and resident amateur photographer Dr John Dudgeon. William Saunders also went on at least one photographic outing with his rival, Lorenzo Fisler. And thanks to the work of French researcher and photo-historian, Édouard de Saint-Ours, we can now add two more names to this list:

Dr Georges Auguste Morache (1837-1908) was appointed as a medical doctor to the newly-opened French legation in Beijing in 1863. In his spare time, Morache pursued several scientific interests, including meteorology and chemistry. He was also an enthusiastic amateur photographer. When fellow French amateur, Paul Champion, visited the capital in the winter of 1865-66, Édouard de Saint-Ours has convincingly shown that they photographed together. Édouard has identified numerous close variants of Champion’s published images as the work of Morache, and that they used plates of different sizes. 3Édouard de Saint-Ours, ‘Georges Auguste Morache (1837–1906): Contexte, création et diffusion de la production d’un amateur photographe à Pékin dans les années 1860’, Master’s dissertation, École du Louvre, Paris, 2016.

We need to give more thought to this kind of cooperation between photographers. For instance, one thing that has troubled me for a long time is the strange absence of surviving photographs from the Shanghai studio of the American Lorenzo Fisler. He was a competitor of William Saunders for many years and regularly advertised his own work and studio. The two of them seem to have photographed together on at least one occasion. Many private and institutional collections of China photographs will include the work of Saunders. His work is well known and appreciated. But only a handful of images by Fisler have so far been identified. Why is this?

Over the years, I have seen many albums of China images catalogued as the work of William Saunders. However, they not infrequently contain close variants of his known work – and also scenes shot in very similar settings at around the same time. They may well all be the work of Saunders, but I think it might be worth carrying out further research to determine whether or not there has been any conflation with the work of Lorenzo Fisler.

TAIPING REBELLION

The Taiping Rebellion, which raged across China from 1850 to 1864, was the deadliest civil war in world history, claiming perhaps as many as 70 million lives. The ultimately unsuccessful rebel armies at one time controlled a significant part of southern China and came close to overthrowing the ruling Qing empire.

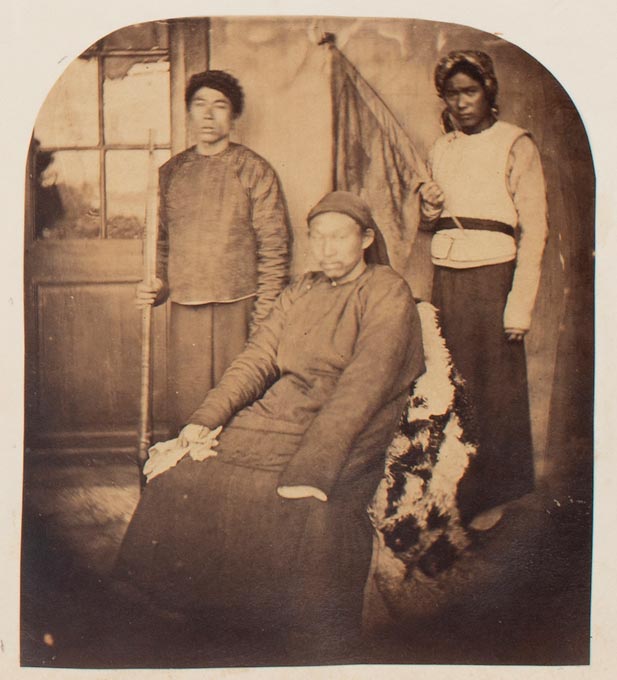

I had never come across a photographic portrait of any rebel military officer or senior official in my past research. My Chinese friends told me that none had been published – or even existed as far as they knew.

On 9 December 1861, the Taiping overran and occupied the treaty-port city of Ningbo. A combination of imperial and foreign armies forced them out a few months later, on 10 May 1862. Ningbo had a number of foreign merchants resident in the city at that time. One of these was George Hart, who ran a successful British trading house. When the rebels arrived in Ningbo, they were keen to cultivate friendly relations with the resident foreigners and convince them that their businesses would flourish under their governance – not only in Ningbo but across the empire. Hart socialised with senior Taiping figures and invited them to his house.

I recently acquired a Hart family album of photos showing family and friends and local Ningbo scenery. The images date from c.1859-1865. It was exciting to find that the album included two portraits of Taiping military officials taken inside Hart’s home.

- Terry Bennett, History of Photography in China 1842-1860 (London: Quaritch, 2009); Terry Bennett, History of Photography in China Western Photographers 1861-1879 (London: Quaritch, 2010); Terry Bennett, History of Photography in China Chinese Photographers 1844-1879 (London: Quaritch, 2013)

- Early articles on Itier’s work: Gilbert Gimon, ‘Jules Itier,’ Prestige de la Photographie, 9, April 1980, pp. 6–31; Gilbert Gimon, ‘Jules Itier, Daguerreotypist,’ History of Photography, 3, July 1981, pp. 225–44. Recent articles: Gilles Massot ‘Jules Itier and the Lagrené Mission’, History of Photography, (2015) 39:4, 319-347; Barbara Staniszewska, ‘Jules Itier (1802-1877) A French Daguerreotypist in Macao’, Estudos De Macau, (2015, pp.42-54)

- Édouard de Saint-Ours, ‘Georges Auguste Morache (1837–1906): Contexte, création et diffusion de la production d’un amateur photographe à Pékin dans les années 1860’, Master’s dissertation, École du Louvre, Paris, 2016.