In December of 2017, my wife and I traveled to Sri Lanka for a holiday. Once there, we unexpectedly encountered obscure remnants of a world famous woman whose name was Julia Margaret Cameron. She had been a controversial and influential photographer in her day, “a priestess of the sun” as she referred to herself in a letter, before she died in Ceylon, now Sri Lanka, in 1879.

A couple of days into our trip, we visited the city of Kandy in central Sri Lanka. On our first morning in the city, our driver, Gameni, a taciturn man who navigated the highways like a talented Kamikaze, wove us through the crowded streets of the city to the Peradeniya Gardens on its outskirts. I knew about the gardens from photographs in my collection made by the commercial photographer, Charles Scowen, in the 1870s. As we walked through the vast grounds abounding with exotic trees, large stretches of green grass, peacocks, monkeys, and walkways filled with local visitors, I recalled the Scowen photographs in my collection, then remembered Julia Margaret Cameron had spent her final years in Ceylon.

As a photographic historian, I knew that the iconic 19th century photographer, Julia Margaret Cameron, had moved To Ceylon from the Isle of Wight with her husband Charles Hay Cameron in 1875. To prepare for every contingency, the Camerons had brought along their coffins, the maid, and a live cow on the ship traveling to the distant shore. (In his biography of Cameron, historian Helmut Gernsheim noted they packed each coffin with china and glass.) Even though Julia expressed joy at being close to her three sons, all living in Ceylon where they managed the family coffee plantations, she must have perceived the voyage as sailing to oblivion.

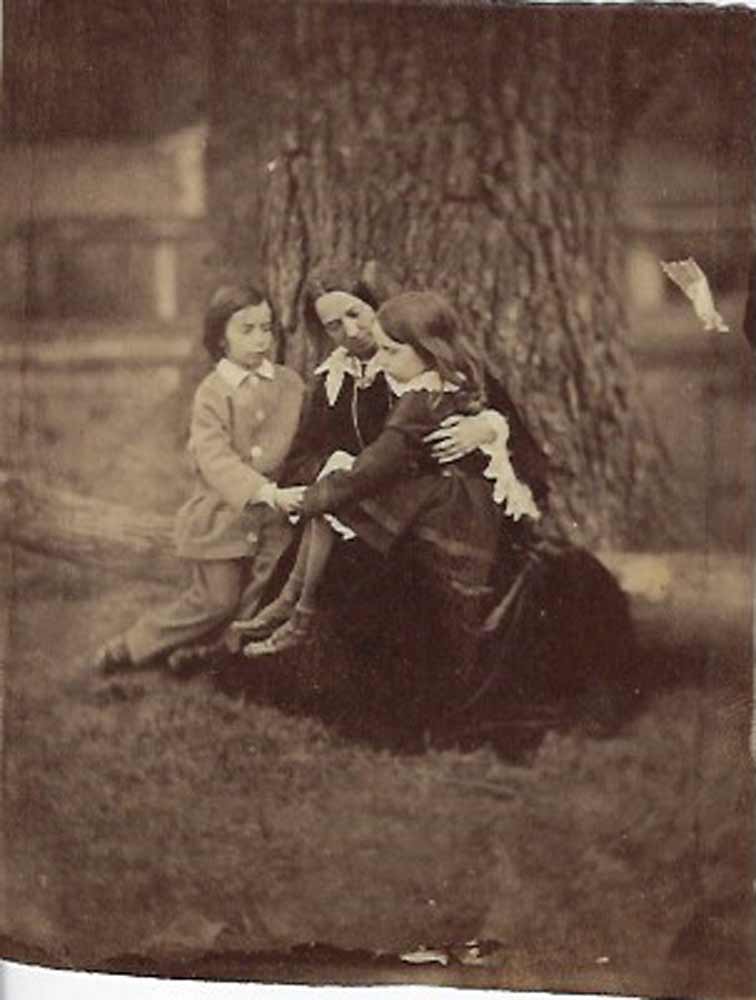

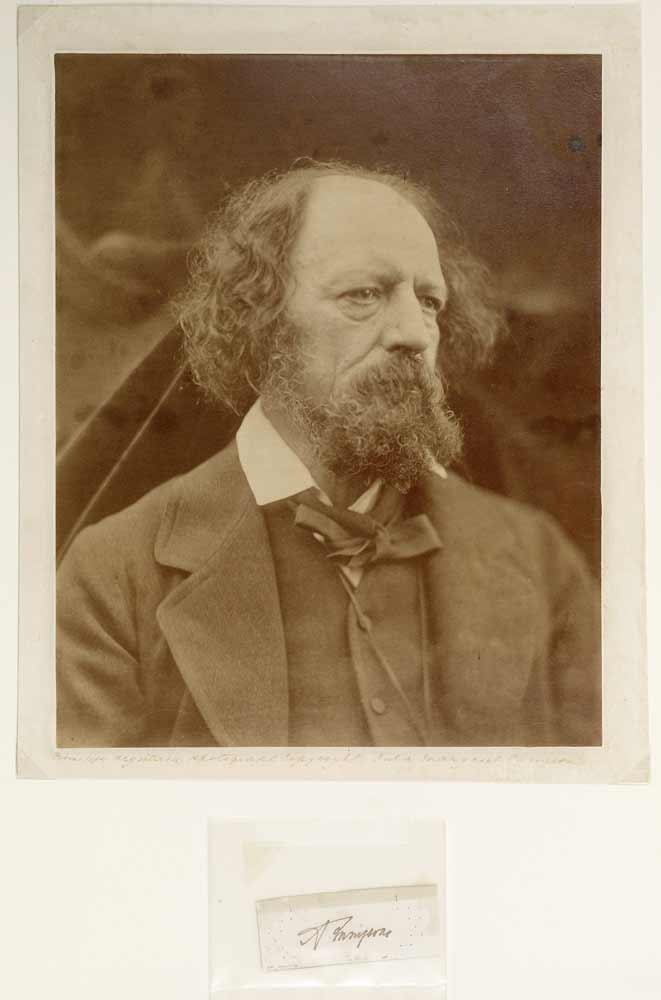

In the numerous books written on her life and work, I remembered seeing a sprinkling of her Ceylonese photographs, primarily images of the local people, but couldn’t recall any specific information about her life during the time she lived there. Most writers seemed to view her three years residence there as an epilogue. Cameron’s fame came from her photographs taken during earlier years spent on the Isle of Wight where she had lived next door to the Tennysons and made a series of romantic allegorical studies, as well as iconic portraits of her famous friends like Tennyson, Herschel, and Darwin.

Cameron’s reputation has continued to evolve. Today, she is a revered figure in the history of photography, her work most recently being celebrated in exhibitions at several major museums. In 2003, the Getty Museum exhibited her photographs, the Metropolitan Museum organized a show in 2013, and the Victoria and Albert one in 2015 to commemorate the 200th anniversary of her birth.

Born Julia Margaret Pattle in Calcutta in 1815, the third child of a French aristocratic mother who had grown up in Pondicherry, India, and an Englishman employed by the British East India Company, she married her husband Charles Hay Cameron in 1838 and bore him six children. She became an accidental photographer after receiving a camera from her daughter and son-in-law as a Christmas present in 1864. Consumed by burning ambition, she transformed herself from an upper class wife and mother to a woman with a romantic vision not above corralling her famous friends as subjects, as well as rounding up any relatives, maids, or pedestrians who caught her fancy. In a prescient September 1, 1877 article in the American publication, Harper’s Weekly, the author notes that the 1870 London Photographic Exhibition included some “beautiful examples” of Mrs. Cameron’s work.

“This lady had made previous exhibitions of her work, but the technical qualities of her manipulation were so startlingly slovenly, in the way of dirty plates and torn films and blurred images, and insufficient definition, that very few took a second look at them. Photographers particularly turned up their noses at them, and held them as examples of the very worst photographs possible; and yet withal there was a mysterious quality about them which one could scarcely explain without analyzing them carefully. There was an amount of art feeling so suggestive that it claimed attention and admiration in spite of the faults which were apparent, and this very suggestiveness tempted many art critics to go into raptures over her work as something beyond the range of ordinary photographic achievement.”

On the day after we walked the botanical gardens and visited the Buddhist temple that supposedly held “Buddha’s tooth”, we prepared to drive to our next stop, Bentota. During a full English breakfast served on the patio of the hotel, I surfed my iPhone to see if I could locate where Julia Margaret Cameron had lived, wondering if any of the places we would visit were close to her home during the time she lived in Ceylon. The name Kalutara popped up in the display window, and much to my surprise, the map of Sri Lanka I’d purchased from an itinerant seller at a tourist sight, showed the town to be only about ten miles from Bentota, where we were booked in a small seaside hotel.

My wife, Mus, agreed that if we were able to locate Cameron’s residence in Kalutara, the trip would take on new dimensions and become an unexpected delight, for as far as I knew no one who had written about the house she lived in or even its location. After a serious web search, I located a geographical description written by Marianne North, a painter of independent means. She had traveled the Orient painting botanical subjects. In Volume I of her autobiography published in 1894, she wrote about a visit to Cameron’s house in Kalutara.

Marianne North had kept diaries of her travels in the Orient, including her visit to the Cameron home. And in 1877, North landed in Galle, Ceylon, and traveled around the island. She painted several scenes in the botanical gardens in Kandy we had visited a couple of days earlier. Those paintings, along with most of her extant work, hang in a building she financed at Kew Botanical Gardens in London. In her book, Recollections of a Happy Life, she writes about her visit to the island, and how, though they had never met before, Mrs. Cameron wrote her several letters inviting her to stay with her at Kalutara. In a brief description of Mr. and Mrs. Cameron, she wrote: “His wife had a most fascinating and caressing manner, and was full of clever talk and originality. She took to me at once, and said it was delightful to meet any one who found pearls in every ugly oyster.” And again, “People often talk to me of the quickness with which young girls make friendships, but I never heard of any so quickly made as this with Mrs. Cameron;”

Julia must have been overwhelmed to have captured an English subject in her home in Ceylon. North continued, “She made up her mind at once she would photograph me, and for three days she kept herself in a fever of excitement about it, but the results have not been approved of at home since she dressed me up in flowing draperies of cashmere wool, let down my hair, and made me stand with spiky cocoa-nut branches running into my head, the noonday sun’s rays dodging my eyes between the leaves as the slight breeze moved them, and told me to look perfectly natural (with a thermometer standing at 96*.)”

North’s description provided the only clues to the location of the house in Kalutara. “Their house stood on a small hill, jutting out into the great river which ran into the sea a quarter of a mile below the house. It was surrounded by cocoa-nuts, casuarinas, mangoes, and breadfruit trees; tame rabbits, squirrels, and mina-birds ran in and out without the slightest fear, while a beautiful tame stag guarded the entrance; monkeys with gray whiskers, and all sorts of fowls, were outside.”

Frequently terrified by our confident driver’s style, we began the long trek from Kandy to Bentota, while Gameni dodged cars, trucks, tuk-tuks, bicycles, dogs, pedestrians, and anything else that moved along the Sri Lankan streets and highways. In a few hours, we reached our Bentota destination. We spent a quiet evening at our seaside hotel enjoying a leisurely dinner after our harrowing ride. The next morning, we toured the grounds of the home of a famous Sri Lankan architect, Geoff Bawa, then stopped at a lakeside hotel for lunch, before taking the 40 minute drive north to the town of Kalutara. The river that Cameron had lived on flowed just a bit north of the center of town where a Buddhist temple of large proportions stood beside the bridge that crossed to the North side of town where a series of dingy shops hugged the road. In the center of town, I located the library, and though the librarians tried to be helpful, they had never heard of Cameron and knew nothing about her life in the town. An Anglican church across the street was locked up and offered no help.

Helmut Gernsheim had written about Cameron as early as 1948, and when back home again, I located in my library a revised second edition of his biography in which he discussed Kalutara: “…this pretty coastal town, which I visited in 1968, lies among coconut palm groves twenty-six miles south of Colombo…” Helmut had been a longtime friend of ours, and I knew that if the house still existed, Gernsheim would have discovered its whereabouts and written in detail about it. After all, he had done the detective work necessary to locate the world’s earliest known photograph, now housed in the University of Texas, Humanities Research Center, along with the rest of his collection.

We decided to cross the bridge beyond the large Buddhist church, and turn west onto the first street that ran parallel to the river, to see if we could locate any signs of a river house from Cameron’s era. The unpaved street bounced us along a road that led past a variety of unimpressive local architecture from bungalows to hovels. Most of the houses looked far more recent than the 1870s. When we reached the shoreline, we knew we’d gone too far. We doubled back, crossed the main highway, which ran all the way from Colombo to Galle, then proceeded east through a twist of streets that paralleled the river. Most of the houses on this side of the highway also appeared to have been constructed far more recently than Cameron’s had been. None resembled the house described by Marianne North.

Ready to call it a day, we stopped at a hotel alongside the river, the Panorama, a place that appeared upscale enough for us to use the facilities. I wandered down to the river, and there, across from the hotel, I spotted a piece of land jutting out from the shore, and more than any other vista, it seemed to match North’s description. This land, with no house visible, appeared to be the only land that intruded beyond the banks. The land stood almost directly below the bridge we’d crossed from the center of town, which would have made it difficult to spot. I photographed the location from the hotel, and when we crossed the bridge leading back to the main section of town, we saw that area now housed a large parking lot for the Buddhist temple. Again, in my research back home, I found a reproduction of North’s painting of the Cameron’s verandah, and the angle of the river seemed to indicate the house stood on the South side of the river, as shown here.

The next day we reached the town of Tangelle along Sri Lanka’s southern coastline. We had been invited to stay at the stunning home of Charlotte Breese, whose daughter is an associate of mine in London. Charlotte, an effusive mother of four very successful young women, had with her journalist husband built an exquisite rambling house beside the ocean with a swimming pool in the courtyard, a place that welcomed many guests during the five months each year the two of them dwelled there. After a warm greeting, our hostess, who already had a houseful of visitors when we arrived, showed us to our large guest room where we quickly settled in. Dinner that night, served on a table placed in the sand by the ocean, had been cooked on an open fire, a meal of fresh fish, vegetables and salad. As we ate, I relayed the story of Julia Margaret Cameron and our visit to Kalutara, while I also expounded upon her prominent place in the world of photography and how she now lay buried in a small church somewhere in the highlands of the Sri Lankan interior. Charlotte, a writer, knowledgeable in many areas, became excited after learning about Cameron’s presence in Ceylon. She immediately saw the romance in our quixotic quest to learn all that we could about an artist who had an enormous impact on photography and now lay forgotten in her final resting place so far from her English home.

The next morning, after breakfast, around a table beside the pool, Charlotte did a bit of computer sleuthing. She showed us on the map the location of a small town with the big name, Bogawantalawa. Buried in the hills of the tea country, the town housed the church where the Camerons had been buried. She suggested shortening our visit with her in order to make the difficult journey into that central mountainous region blanketed green with tea plantations. She recommended places where we should stay for a couple of nights while we learned all we could about the life the Camerons led during their time in Ceylon. To stay in close proximity to the plantations the couple once owned would allow us to spend a day pursuing what might be left of their presence, if anything, and to locate the graves in St. Mary’s Church. When I explained the lack of awareness of Cameron in Kalutara. Charlotte felt certain she knew people living in Colombo who could cast some insight into Cameron’s doings in Ceylon.

We spent a wonderful day with her in the Tangalle area, highlighted by a boat trip in a lagoon brimming with bird life and breathtaking sunset views, one of Charlotte’s favorite spots. The next morning we prepared to set off. Charlotte had located a new driver to replace Gameni, the first driver she had also found for us. He needed to stay home (he lived near Charlotte) to tend to some family business. Dimuthu, our new driver, also lived nearby, and he drove a new brand new baby blue Prius with wi-fi and comfortable seats. Dimuthu proved to be far less aggressive behind the wheel as he protected his new car like a father protects his firstborn.

We had booked an unusual rental at Charlotte’s suggestion, one of three cottages nestled above the small hill town of Hapulale. Each cottage contained three bedrooms, a view of the entire valley below, and each came complete with a cook and a houseboy, a new experience for us. However, the drive into the mountains proved treacherous, a twisting 40 kilometer jaunt along a winding road that morphed from the bright sunshine we’d grown accustomed to into a dense fog and drizzle that made every turn a challenge, and the pace snail-like with the always cautious Dimuthu behind the wheel.

After passing through the town of Hapulale, and a location search along a pitch-black mountainside during an intense downpour, we arrived at the small office of the Mountain View Cottages, hurried inside, and waited forty-five minutes for the downpour to cease in order to be taken to our cottage. The cottage, down some two dozens slippery rock stairs without lights or rails for guidance, displayed a living room with an other-day quaintness, mismatched furniture, a fireplace, and in the front of the room, a patio that overlooked the vast valley below. A dinner was prepared for us by the cook which we ate in front of a much appreciated fire the houseboy started to warm the damp room.

During the night, I woke to a pulled muscle in my back, and by morning my entire back had gone into spasms, leaving me in intense pain and unable to move. The rain had been replaced by fog. Now my wife had our driver take her into the village below, and she returned with medication and a Thai masseur, who set to work trying to loosen the muscles in my back. So passed a long day. Dimuthu had no one to drive. The cottage lacked wi-fi, television or radio, and I could either spend my time sleeping or groaning.

We had lost this day planned to hunt down the Cameron plantation, and the next day we were scheduled to drive to Colombo, a drive of several hours through the mountainous terrain. In the morning, my back felt about the same as I grimaced my way up the stairs to where the car was located. For the first hour or so, I felt great discomfort, but between my wife’s morning back massage, and the medication, mostly aspirin, my back began to loosen up. Within an hour, we reached the turn-off that would lead us to Bogawantalawa, a small town in the midst of the tea plantations about 150 kilometers from Colombo. We couldn’t be this close and not visit, and we decided we would drive the three hours necessary through the hilly terrain to reach the church the Camerons were buried in.

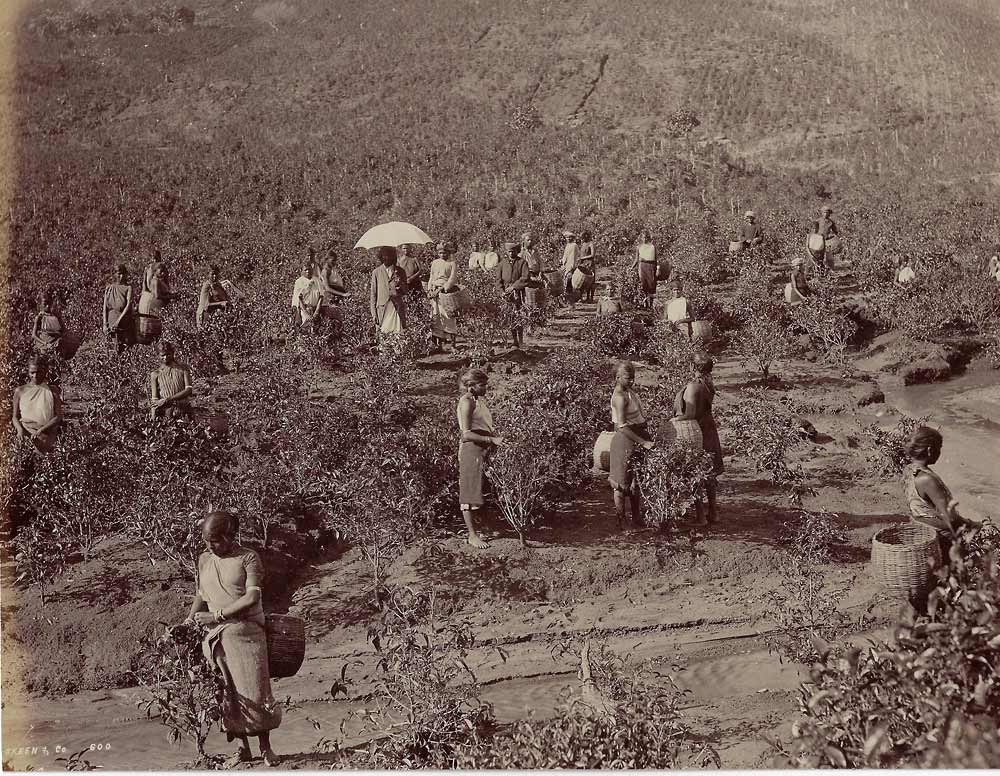

The road wound along the hills, surrounded by green seas of tea planted in every direction. As we climbed higher and higher into tea country, the going proved slow with continuous curves revealing new and stunning scenery, At one point we encountered a group of women at a weighing station with their large sacks full of tea. Mus asked Dimuthu to stop in order to photograph the women, and later, at home, I uncovered a 150-year-old photograph of the tea gathering process which demonstrated that nothing much had changed through the years.

Three hours from the turn-off, and well past our lunch hour, we reached the outskirts of the town of Bogawantalawa, and nothing had quite prepared us for what we saw. Looking down from an elevation of some 4500 feet, we could see a layering of switchbacks that led down to the town nestled in a deep valley. We passed a group of ardent western bicyclists, each in uniform, laboriously peddling uphill. “Are they nuts?” I asked my wife who only laughed.

After endless turns, we reached the bottom of the hill, passed through the small town, and stopped to ask locals for directions to the church. An older man told Dimithu to continue straight on towards the town of Hatton, where we would encounter the church along the road.

A stone sign identified the small religious structure standing above a cobbled driveway that looked as if it had not changed since Julia Margaret Cameron attended services there, perhaps with her son. Her non-religious husband had long been a follower of Jeremy Bentham, the forward thinking philosopher of utilitarian ideas. The Camerons, at Julia’s insistence no doubt, did contribute the funds for three stained glass windows inside St. Mary’s church.

Walking up the cobblestone driveway, once used by worshippers who arrived on horseback or in ox-carts, Mus and I paused in front of the church entrance, which was closed off. To our left stood a church graveyard, and the first two graves we encountered belonged to Julia Margaret Cameron and her husband, Charles Hay Cameron.

How forlorn their graves looked, unattended, unadorned, housing this woman, perhaps in the very coffin she had brought on the ship all the way from England, a woman whose photographs still stirred thousands with their beauty, and whose name was spoken with reverence by lovers of photography around Europe and the States. I could not help thinking of the Percy Shelley poem Mus and I had used once in the forward we wrote to a photography book, a sonnet about Ozymandias, another name for Ramses II, whose half-buried stone plaque proclaimed:

And on the pedestal, these words appear:

My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings;

Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!

The poem concludes with a reminder that whatever great empire he once ruled is now lost and buried beneath the sands of time. Of course, Cameron’s work is far from lost. In fact, an album that Julia Margaret Cameron made for her only daughter, Julia, a young woman who died two years before Cameron left for Ceylon, is currently on hold as the Brits try to raise funds to match its purchase in the 3 million pound range. Some of her most important individual pieces bring six figure prices privately or in the auction market. This vivacious, dynamic woman had cowed the mighty men of England into posing before her lens, and in so doing immortalized them for generations to come.

In the year before she died, Julia returned to England with her husband and son Hardinge, for one final visit. She had planned to stay only a month, but extended the visit to six. Victoria C. Olsen, in the last chapter of her comprehensive biography on the life of Julia Margaret Cameron, explained the reason Hardinge had returned to England, because of illness. But that illness may have lingered after the family returned to Kalutara. Within a month of their return, both Julia and her husband, Charles, accompanied their son to a cottage on one of their plantations, Glencairn Estate in Nuwara Eliya, Dioya Valley, some 16 miles from St. Mary’s church. The family hoped the higher altitude and cooler air would help Hardinge to recover, which he did, as he lived on for another thirty-two years. But sadly, the change of climate caused Julia to take sick with a cold, which may have rapidly developed into pneumonia during a time when the use of antibiotics was unknown. She passed away ten days after they arrived.

According to legend (source unknown but possibly a son), her last word in this plantation cottage came after a glance at the evening sky, a key word that dominated her entire adult life, “beautiful.” If such an idea as an afterlife exists, and if somehow Julia Margaret Cameron’s spirit could rise up above that slab of stone that is slowly obliterating her name, this is the view she would see from her tombstone, certainly a scene that would please her through all eternity.

We left the church behind, and with much to contemplate regarding fame and mortality, we continued on our way, finally locating a place to stop for lunch at four in the afternoon. Another long and exhausting four hours of driving brought us to Colombo and our walled hotel in an upscale section of the city.

The next day, our last day in Sri Lanka, we set out to find out what we could about Cameron in Ceylon. We hired a three-wheeled tuk-tuk for the day, and we first visited a Photographer’s Association, then the main library, and finally the National Archives. With limited time to research, no information could be found anywhere, and not one person we spoke with in any of the locations we visited seemed to know the name of the great photographer, Julia Margaret Cameron.

In an article published in 2005 in The Island, a daily newspaper published in English, Leelananda De Silva, a Sri-Lankan local, wrote about both Camerons. Julia’s husband, Charles, had been primarily responsible for drafting the Penal Code for Ceylon a few years before he and Julia met. In the best Bentham tradition, Charles set up laws for the country that ensured, “all persons were equal before the law.”

De Silva wrote the following about the couple: “With these achievements and their connections with this country, Julia Margaret and Charles deserve a fitting memorial. There has been considerable activity recently to celebrate the centenary of the arrival of Leonard Woolf to this country in 1904. He deserves it. His novel, ‘Village in the Jungle’ and also his Ceylon diaries are literary landmarks.” Woolf spent seven years in Ceylon as a minor civil servant, returned to England, and became involved with the Bloomsbury Group where he met and married Virginia Woolf, the daughter of Julia Duckworth, a niece, and one of the favorite subjects of her aunt, Julia Margaret Cameron.

Thirteen years after De Silva’s suggestion of building a fitting memorial to the Camerons, we were unable to locate any mention of either Cameron in the public view.

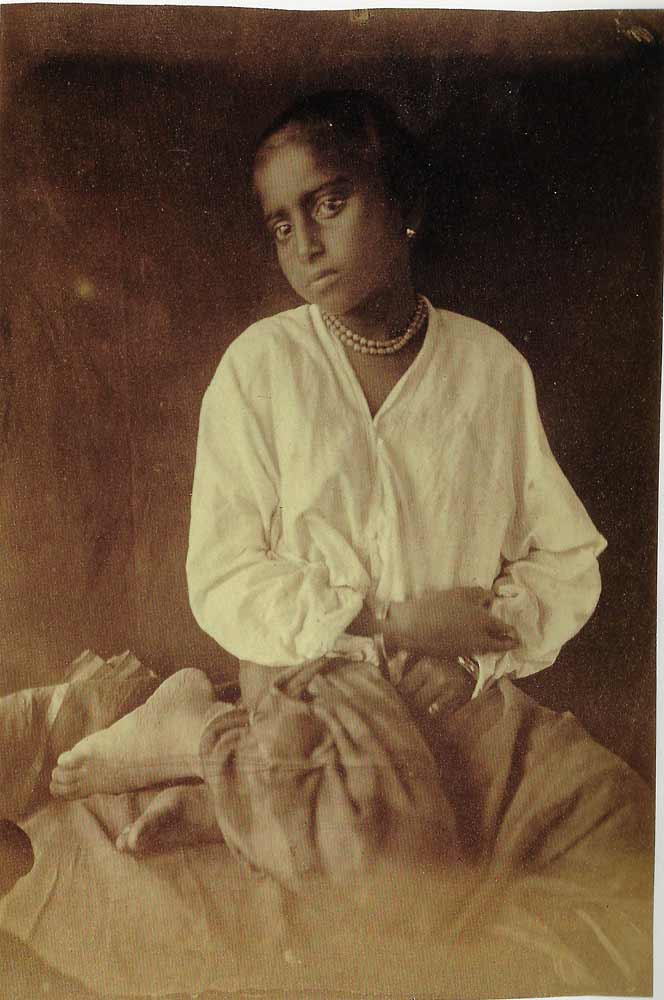

Articles and books that discuss Cameron in Ceylon critique the few Cameron photographs taken of the locals. In Olsen’s biography, she details Cameron’s European attitude towards the natives. “Like most of her British contemporaries, Cameron believed that ‘Orientals’ (a term she used to include Southeast Asians and Arabs) were fundamentally lazy, and her letters are filled with anecdotes of her finding what she was looking for in their behaviour.” Most writers conclude the images she took in Ceylon, about thirty photographs extant, to be more ethnographic than aesthetic. Perhaps, for this reason, and with the exception of Olsen’s biography, few details have been offered on the time Cameron spent living in Ceylon. Olsen also clarifies the confusion around where she died, whether in Kalutara (Wikipedia and others) or in the hills where their plantations functioned. However, it is safe to say that this photo of a Ceylon Girl below contradicts the general negative evaluation of her Sri Lanka photographs:

Many of Cameron’s Ceylon photographs are reproduced in the large volume done by Colin Ford and Julian Cox titled, Julia Margaret Cameron, The Complete Photographs, a monumental work with extensive references to information on this woman and her fascinating life. In the previously quoted Harper’s Weekly article written in 1877, the author noted: “She has been fortunate in securing fine models; and with these she has followed the subjects of the of the old masters in her composition and in her method of lighting, until she has given us some results that are more pleasing and harmonious than photography usually is, and she has helped materially to establish for photography its coveted claim of being a fine art.”

Standing over her grave beside that small church, I could not help but be struck by the irony of her legacy, and how the memory of her appeared to be literally buried here in this beautiful but desolate place. Dimuthu located a local woman who served as a caretaker of the church. But, she was new to the job, and she knew nothing about Cameron or her legacy. She allowed us inside the locked church, and before we left, I gave her a 1000 rupees (about $7) to buy flowers for the grave, our tribute to this modern Oxymandias spending eternity so far from home.