Your editor has asked me to answer the question “Why did you begin to collect photographs?” In order to answer, I have to go back over fifty years, so you must forgive me if memory fails, but here goes…

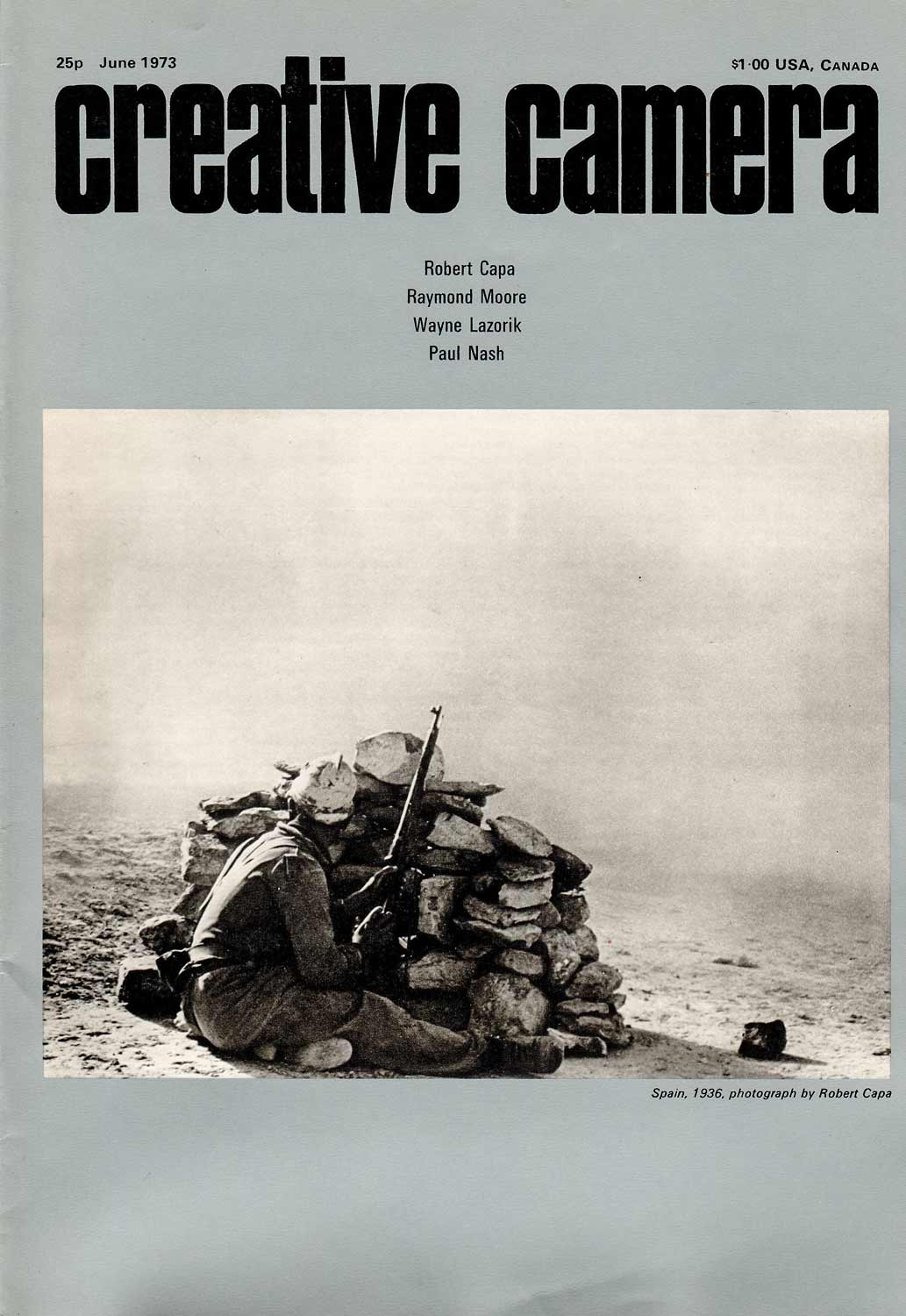

In the late 1960s I was a student at university. I had no money and struggled to afford the two shillings and sixpence each month to buy Creative Camera Owner magazine. But I knew I had to have it. It had evolved from Camera Owner magazine and had been edited since 1966 by Bill Jay. In 1968 it became Creative Camera, a sometimes infuriating but more often inspirational guide to what photography could aspire to.

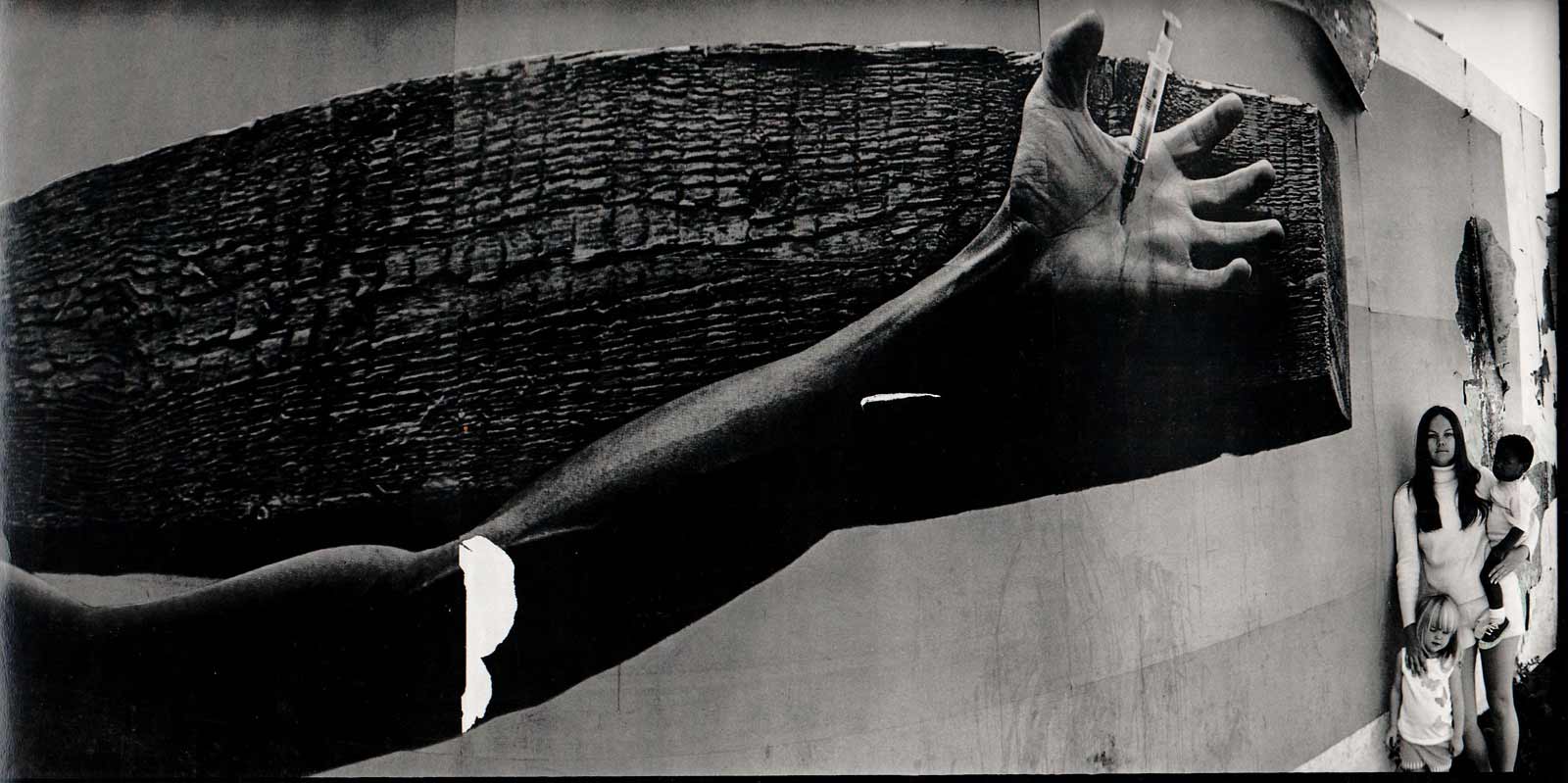

I had taken my own photographs, and had developed and printed them, since Sixth Form at school. Uninspired by the tedious conservatism and obsession with the technical side of photography by all the hobbyist magazines then available, Creative Camera magazine was a blast of radicalism. It declared that the image itself and the vision of the photographer were what mattered, and that innovation and iconoclasm were as important as reverence for an accepted canon of masterpieces. The magazine inspired you to take photographs in a different way, if you were a photographer; and to consider the photograph as an object of worth in its own right.

It is as well to remember what did not exist then, that we now take for granted. In the UK there were no dealers in photographs; no specialist galleries; no museum exhibitions; no specialist auctions. The museum and curatorial world looked down its nose at any suggestion that you could frame a photograph and hang it on a gallery wall, as you might an Old Master print. In spite of all this it felt like an exciting time, and as luck would have it, as the Sixties turned into the Seventies, it became more exciting.

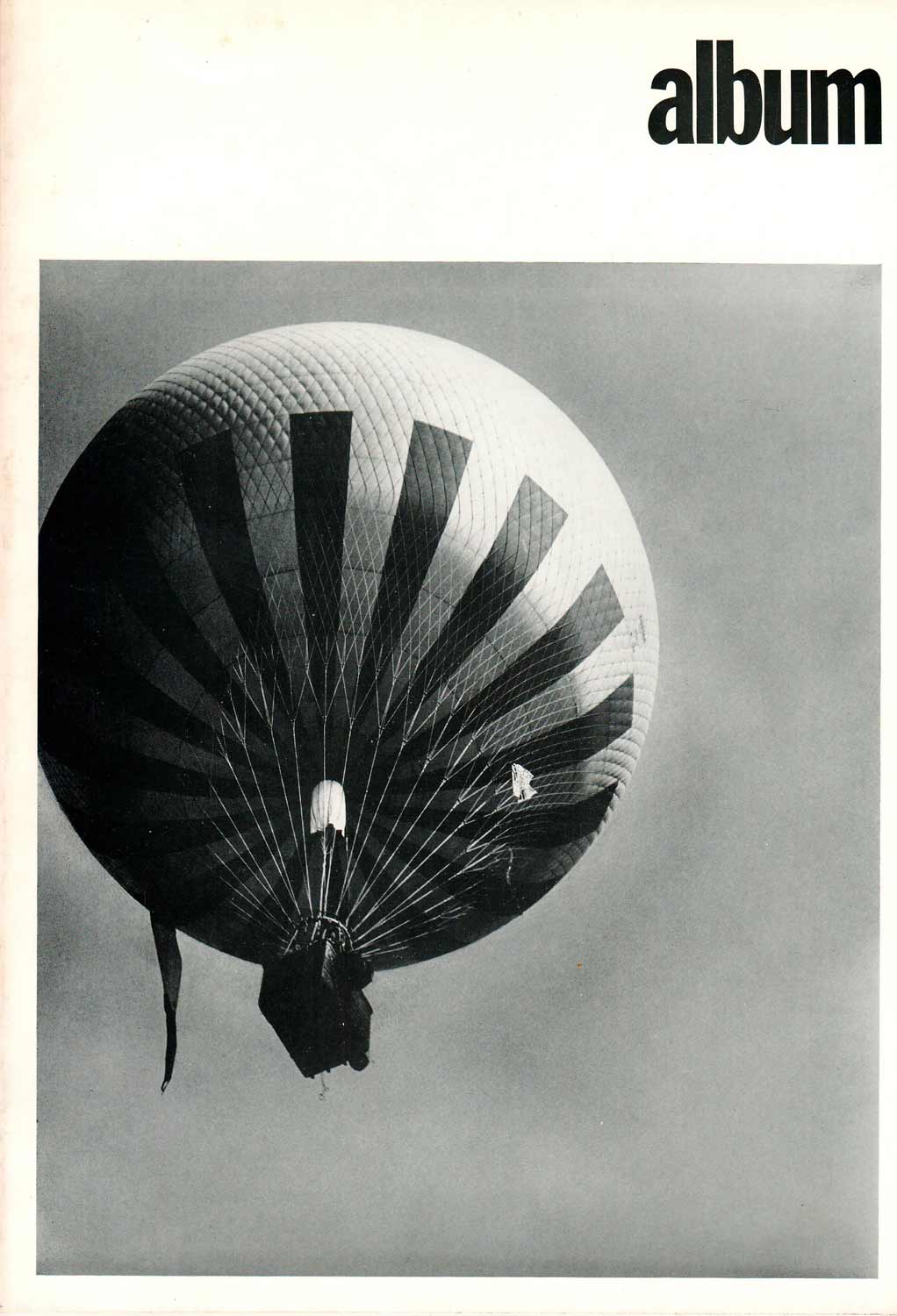

Bill Jay was about to leave Creative Camera in order to become the founder and editor of a new magazine, “Album“ in 1970. By the standards of the time Album had high production values and thus higher costs, which contributed to its short life. By 1971 it had closed. I count myself fortunate to possess a full set of all twelve editions of this inspirational magazine. Meanwhile Creative Camera magazine continued to appear, for a time under the editorship of its brave and far-sighted owner and publisher, Colin Osman, and then with Peter Turner as editor.

Bill Jay’s first editorial at Album was a savage condemnation of the state of British photography. He railed at the fact that “the clear mainstream of photography, that sprang from Victorian photographers, surged across the Atlantic… back in Britain our photographers drifted into sidestreams… the fools. They forgot the golden rule of great photography – no one gives a damn whether or not photographs are Art. Photography is photography. It was born an extremely mature and powerful means of communication.” But he went on to say that there were a few exceptions, and mentioned contemporary photographers such as Thurston Hopkins, George Rodger, Don McCullin and David Hurn. He identified up and coming young photographers such as Andrew Lanyon, Homer Sykes, and Paddy Summerfield. And that was when it occurred to me: perhaps I could collect some of their work?

Right from the first issue of Album there was a small paragraph at the back which said “If you would like an original print from any photograph reproduced in this magazine please drop us a line and we will be happy to arrange it, if at all possible.” Creative Camera did not have a similar stated policy, but I eventually contacted Peter Turner and he confirmed that they could offer the same arrangement. Album listed the photographers they featured and stated prices. With each issue the list grew longer. It ranged from £8 for a print by Sylvester Jacobs and Paddy Summerfield to £60 for a Bill Brandt. At one point David Hurn and Patrick Ward reduced their print prices from £15 to £5 and to £1 for students. In 1970 I had just started my first job and had an income for the first time in my life, but even so I had to budget carefully. For example the £60 Bill Brandt print is the equivalent of £900 today, and although that may still seem reasonable in today’s market, it was way beyond my means.

Three other things happened to change the scene at that time; in January 1971 Sue Davies opened the doors of The Photographers’ Gallery, and later in the same year Philippe Garner began specialist sales of photographs at Sotheby’s. In late 1970, Bill Jay had established the first gallery dedicated to photographs in the UK. It was called “Do Not Bend”, and was located in the lower ground floor of a house just down the road from Album’s office in Holland Park. It was run by Clody Hall Dare. I remember visiting the gallery one early evening to see the exhibition “Plastic Love Dream” by Roger Mertin. Subsequently I bought there two prints by Bettina Gruber, the daughter of Fritz Gruber, organiser of the exhibition Photokina at Cologne. Early purchases through Creative Camera included prints by Gerry Badger, one from Chris Killip’s series on the Isle of Man, and a lovely print by Raymond Moore of a door handle in Cyprus. Creative Camera received many submissions from young American photographers, and I eventually bought a print by Todd Walker and one by Robert Adams, then completely unknown over here. Two prints by the Italian photographer Gianni Berengo Gardin are still in my collection. I loved his use of his wide angle lens on his Leica, though he is less well known than his compatriot Mario Giacomelli.

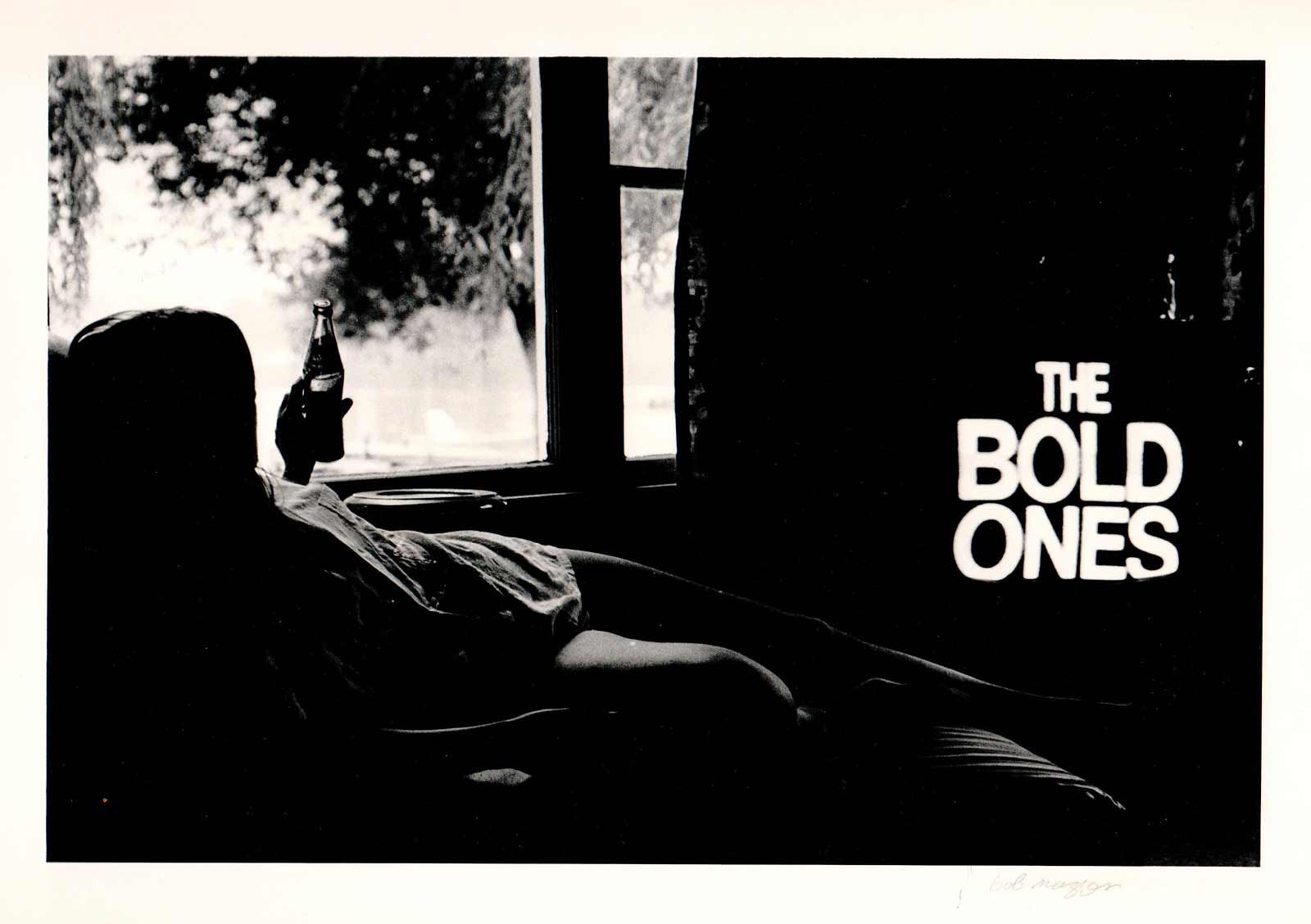

Almost as soon as The Photographers’ Gallery opened Sue Davies established a print-selling operation. In the early days the “Print Room” was a cupboard behind the reception desk, and print sales were largely in the hands of Dorothy Bohm, herself a photographer of some note. Early on the gallery held an exhibition of 8 Young Photographers, and I still have the list of photographers and prints with their prices. These ranged from £3 to £10 each. I bought two prints by Bob Mazzer which he had taken on a trip across America in 1969. Both were scenes in Michigan, one of which reminded me of David Hockney’s painting “A Bigger Splash”. Later purchases included a print by Penny Tweedie from her Bangladesh series; a Fay Godwin print of Barbary Castle Clump, which remains a favourite of mine; and a print by the American photographer Jim Alinder in his signature panoramic format.

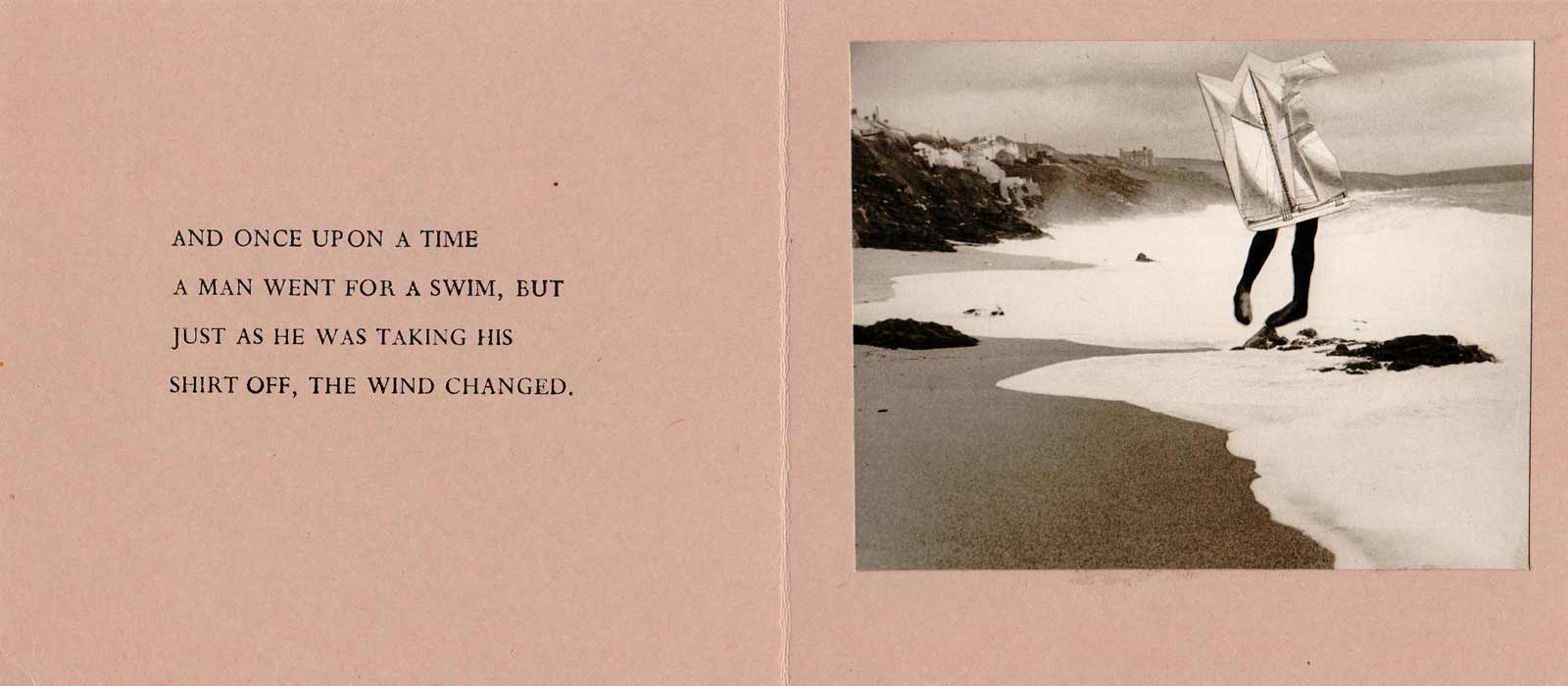

Obtaining prints from Album under their scheme was slightly hit and miss, as I recall, but I was able to buy a lovely piece by George Rodger, a later print from his Tunisia series originally taken in 1957; and two unusual photomontages by Andrew Lanyon. He is the son of the St Ives school painter Peter Lanyon, who did interesting work in those years but has himself become better known as a painter. I can remember visiting David Hurn at his London home in pursuit of one of his prints, after a call to Album, and being mesmerised by the mammoth size print of “Behind the Gare St. Lazare” by Cartier-Bresson that hung on his wall.

My last visit to Do Not Bend Gallery before it closed was to see an Emmet Gowin exhibition. I had long admired the extended series of photographs of his wife and family in Danville, Connecticut, that he took in the 1960s. He used a large format camera and the print quality was superb. That, as well as the surreal and dreamlike quality of the images, meant that I longed to own a print.

One of the final purchases I made from Creative Camera in the early Seventies was a delightful late 1960s print of a Ruthenian Clarinettist by Erich Auerbach, a British photographer born in Czechoslovakia, who worked for magazines and the Sunday papers and specialised in photographs of musicians.

It is easier to describe what I collected and from whom, than why. Why did I feel the need to collect original prints rather than just enjoy reproductions in books? For me there is something about the physical presence of the print, its paper type and particular sheen, that is incomparably better than a book illustration. Once you have started collecting it seems foolish not to go on and acquire more, randomly at first but in the hope that some sort of coherence to the accumulation will emerge. (It never does.) At that particular moment as the 1960s became the 1970s I felt I was part of an insurgence; that we were in Evelyn Waugh’s phrase “Contra Mundum” challenging the stuffy establishment philistines. And the thing is… that original excitement has never gone away.