My father, Erwin, came to New York in July 1939 to advance his photographic career. He had just finished a one-year contract with Vogue (Paris) where he had produced that most memorable image of Lisa Fonssagrives floating in her dress on the Eiffel Tower. Erwin was then hoping to arrange a better contract from Harper’s Bazaar and other magazines.

He had packed a hundred of his best B&W prints into a fine leather briefcase which hewas unaware could brand him in America as a German traveling salesman. He had also arrived on the French flagship, the Normandie with only a few words of broken English and in a tweed jacket that he had hand-made to measure in Paris and which he was to describe wearing it was “like being locked in a red hot steam bath” in New York.

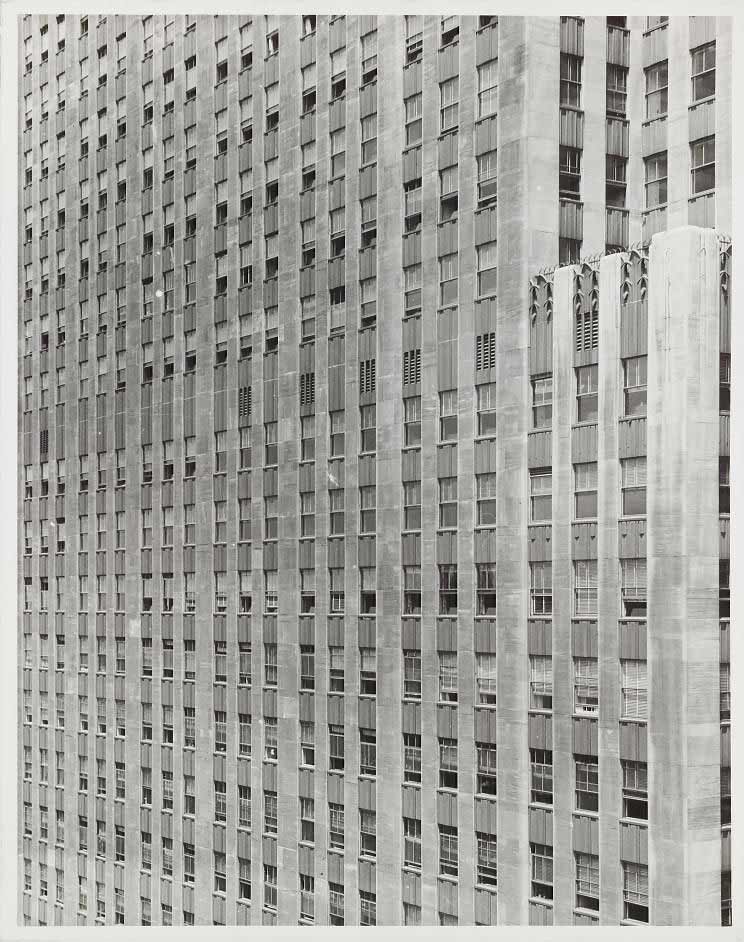

The famous French editor, Lucien Vogel, had recommended Erwin to the publisher of Life. The magazine was located in Rockefeller Center whose cathedral-like sky-rise struck Erwin with “a positively mystical feeling for this world of tomorrow.” He was thrilled to take the incredibly speedy elevator which brought him to the 35th floor in twelve seconds. He was to describe that occasion as the very first time that he had entered an air-conditioned room mercifully situated on top of a modern Babel surrounded by a blistering heat.

Erwin had hoped to see Henry Luce, the boss of Time-Life, for whom he had brought a flattering letter of introduction from Vogel. Fortunately, as Luce had left for Europe the previous day, his secretary- impressed by Vogel’s praises- passed him on to an arts editor along the corridor: Alexander King.

Blumenfeld was to describe Alex in his autobiography, Eye to I, as “an androgynous creature of my own age, with a pink bow- tie, reddish hair and a wolfish grin.” He had come from Vienna as a teenager and now spoke perfect American without a pause for breath.

Erwin wrote sardonically: “Although we had never seen each other in our lives, he fell upon me as if I were an old friend. “Of course we know each other, Irving, we met in Paris,” he said going straight onto first name terms. Within ten minutes he had promoted me to being his cousin.”

Alex blabbered at some length that to become a Life editor one had to be a chronic alcoholic. While talking, Alex looked over all of Erwin’s 100 photos with “an interest, an understanding and an enthusiasm that I have never found in the world of journalism before or since.”

Shadowy assistants kept coming into the office with images for Alex to look at. He dealt “every thing with a virtuoso display of clowning, laughed at all of them and introduced me to every one of these nonentities as “the greatest living photographer” to which every one of them replied: ‘Hello, Irving.”

Apparently then, “with the door wide open, Alex took out a hypodermic filled with a milky fluid and quite unselfconsciously struck the needle into his arm whispering: “Vitamin E ‘! ”

This act didn’t arouse suspicion in my father but when King promised to give him a big feature as top photographer in the next issue of Life, he began to doubt Alex’s sanity. Grabbing a handful of Erwin’s photos, Alex took him to the office next to his to introduce him to Wilson Hicks, the Picture Editor. My father wrote that this dull schmuck stared at the pix without seeing them. King declared bombastically: ”Speaking about pictures…Blumenfeld’s are the tops!”

Hicks nodded. ”OK.”

Then Hicks took out Erwin’s photo of Claus Slutter’s Death of Christ and exclaimed “What an Ad for Pepsodent!”

On which King dragged Erwin out into the corridor and enthusiastically declared: “’Irving, you’re made!’ What else can I do for you?” My father, slightly bewildered, replied that as a photographer he wanted to see New York at its best.

Looking at his watch, King diabolically responded that in exactly 25 minutes his wish would be granted but that in the meantime he could earn $500 for ten of the pix in his attaché case which would be published in a tiny photo magazine called Minicam which he, Alex, edited.

Exactly half an hour later, Alex took Erwin, who in that short time had become “the greatest living photographer,” to the penthouse of the building. There was a telescope on a stand from which one could look at the endless windows of Rockefeller Center glistening in the July sun. Through the telescope Erwin saw a blonde girl typing and King told him that in sixty seconds he would see a changing story. Indeed behind the typist entered a man who kissed the back of her neck. She got up and he started to open her blouse. King explained that the stockbroker came every day at exactly the same time to carry out this scenario. For my father this was American punctual eroticism.

Before King went off to lunch and my father went to a highly successful meeting at Harper’s Bazaar, King excused himself because at the last moment he had left his wallet in his office. Could Blumenfeld lend him $20? Erwin was happy to let King have it. Over the years of their friendship, this became one of many repeated “borrowings”- none of which my father was ever to recover. Only later did he learn how expensive Alex’s coke habit was. The photos in Life did appear in “Speaking of Pictures…” shortly thereafter and received global recognition. A few pix were used in Minicam but Alex never paid for them. Years later Erwin discovered that he had fallen for a one act play that King had directed students from a theatre school to perform when he had to show European visitors the “Best” of Manhattan life.

Five years and histories later, as a teenager in New York, I was introduced to Alex. My father (whose many covers were by-then decorating Harper’s Bazaar) frequently invited Alex to family dinners. The two had much in common: both were European Jews of the same age, German was their first language, both wore butterfly ties, loved women, were truly superb story tellers, and had multiple talents in the publishing and artistic worlds.

In his verbal juggling careers, Alex was first a successful book illustrator, then in the late twenties and early thirties he set up a primitive art painting centre for Haitians in Port-au-Prince, returned to New York as an art editor for Vanity Fair, joined Life, turned to Playwriting for Broadway, then became a TV personality via the Jack Paar show, and ultimately wrote books. All of these were accompanied by drug addiction, a serious long lasting kidney problem, and four wives! (The one who fascinated me was an outstanding ballerina who had posed as a young Snow White for Walt Disney’s film.

My father admired the way King could mock the art world like a “frito bandito.” I was astounded to hear from Alex’s arsenal that modern art was “a putrescent coma” and that art directors were “Adenoid baboons.” Such descriptions were often mixed with ribald Yiddish expressions such as :”Zol im vaksn ‘burikes in pupik, un zol er pishn mit borsht!’’ (May beets grow in his navel so he can piss borscht!)

Alex was as proud of the Chinese scenes he painted for a kosher restaurant in lower Manhattan as he was for his dramatic efforts on Broadway Every half year or so, he would regale us with the latest tale from the narcotics rehabilitation Hospital in Lexington Kentucky to which he was frequently confined. Later he would describe in his book, “Mine Enemy Grows Older,” how he was stuck in a drab isolation cubicle with nothing to read but an issue of the Saturday Evening Post:

“It was a walking nightmare of the most sinister dimension and variety. My whole past life was insidiously evoked, ruefully demonstrated, and mercilessly indicted. It suddenly came to me that the reason my three marriages had smashed up was, simply, that they had been frivolously ratified on the wrong kind of mattresses.”

Yes, my father was highly amused to watch King become a celebrated TV personality but always looked back to his first unbelievable encounter with King some 20 years earlier. He recognized that King had baptized him in America as “the greatest living photographer.” Writing in his autobiography Erwin added that coming to New York in July 1939 had been “The best decision of my life.”