More often than not, when discussion turns to the pioneering days of modern photojournalism, a number of names instantly spring to mind. Henri Cartier-Bresson, Martin Munkásci and André Kertész are just a handful who tend to be synonymous with the genre. However, arguably one of the “founding fathers of reportage” is usually missing from this list. A man who was at the very forefront of this photographic revolution and who, like those mentioned above, did much to change the world of photography. His name is Kurt Hutton – arguably every bit as influential and ground-breaking as his counterparts but sadly overlooked today.

A group of girls anxiously awaiting partners at a mining village dance. Original Publication: Picture Post – 1270 – Mayfair Danceband Plays For A Mining Village Dance – pub. 1942 (Photo by Kurt Hutton/Getty Images)

A crowded beach on the Isle of Man, complete with fund-raiser from the Salvation Army. Original Publication: Picture Post – 196 – The Isle Of Man – pub. 1939 (Photo by Kurt Hutton/Getty Images)

Kurt Hubschmann was born in Strasbourg, Alsace, in 1893, then part of Germany, now France. He originally studied law at Oxford between 1911 and 1913 but his efforts were somewhat half-hearted. The outbreak of World War I in 1914 provided the young German with an excuse to abandon his academic studies and he was soon was promoted to the rank of Officer in the German Cavalry. Following the cessation of hostilities in 1918 he decided to remain in Germany and started seriously thinking about his future career. Though attracted to photography as a youth, he initially didn’t regard it as a serious occupation – more a hobby. Entirely self-taught, he eventually took the plunge in the early 1920s and in 1923 set up his own portrait studio in Berlin. Though potentially lucrative, portraiture soon bored him – he much preferred the realism of reportage and as a result, in 1929 he embarked on a freelance career.

The eldest daughter of a large family polishes shoes on the doorstep. Original Publication: Picture Post – 2017 – Bringing Up A Very Big Family – pub. 1945 (Photo by Kurt Hutton/Getty Images)

Working on behalf of Simon Guttmann’s Dephot agency, he submitted a wide variety of photo-essays to several of the newly established German photo-magazines such as the Munich Illustrated Press and the Berliner Illustrated. The switch to photojournalism under the genius tutelage of Picture Editor Stefan Lorant, who worked for several of these picture magazines, together with the astute guidance of photographer Felix Man (born Hans Baumann), proved to be major turning point in Hutton’s career. Man and Lorant introduced him to the newly invented small format camera which, up to that point, had been dismissed as a mere toy by a number of the more established names in professional photographic circles. However, Hutton persevered with this new technology, which would rapidly revolutionise the world of reportage photography.

A hotel commissionaire talking to a small dachshund dog in Piccadilly Circus, London. Original Publication: Picture Post – 2 – In The Heart of the Empire – pub. 1938 (Photo by Kurt Hutton/Getty Images)

Two women in an open-top car driving past a sign advertising Hollywood’s Olympic drive-in theatre in Los Angeles, California. Original Publication: Picture Post – 5298 – Two Men In Hollywood – pub. 1951 (Photo by Kurt Hutton/Getty Images)

Hubschmann finally settled in London in 1934, adopting the name Hutton in 1937, primarily due to the increasing anti-German feeling in Britain. Once again working with Lorant, Hutton spent four years as staff photographer at the Weekly Illustrated magazine, working alongside former colleague Felix Man and also James Jarche, before joining legendary Picture Post magazine when it was founded in 1938. One of only a handful of staffers, Hutton – together with Mann and a British photographer by the name of Haywood Magee, were perhaps as responsible as Lorant for the immediate and enormous success of the magazine. Using his trademark Leica, the ability to effortlessly capture the essence of both the British working classes as well as the more affluent at work and at play can be considered to be the genius of Hutton. Hutton was prolific in the early days of Picture Post and it was not uncommon for several of his photo essays to appear in each issue.

Two young women enjoying themselves on the ‘Caterpillar’ ride at Southend Fair, Essex, October 1938. Original Publication: Picture Post – 409 -October Month Of Fairs – pub. 8th October 1938 (Photo by Kurt Hutton/Picture Post/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Due to his German background, Hutton was interred as an enemy alien between 1940 and 1941 but after much string-pulling by the Hulton Press management he was released and eventually became a British citizen in 1949. He remained with the magazine until his effective retirement in 1950 though he continued to contribute the occasional photo-story on a freelance basis until the demise of the magazine in 1957 – the only photographer to contribute material from the first to last issue. Perhaps Hutton’s only real failure throughout his career – and a charge that could also be levelled at his employers who didn’t even credit photographers until 1941 – was his inability to publicise his name or his work. It is perhaps for this reason why the name of Kurt Hutton is not mentioned in the same breath at Cartier-Bresson and the like.

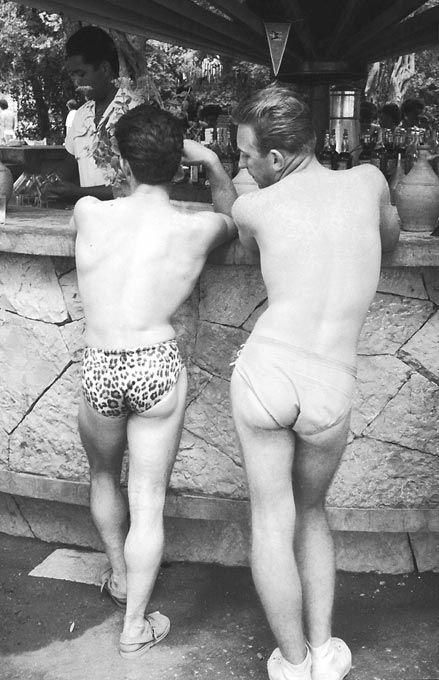

A badly sun-burned holidaymaker admires his friend’s leopard-print briefs, while standing at the bar of a holiday camp on Corfu. Original Publication: Picture Post – 7364 – A Place in the Sun for You – pub. 1954 (Photo by Kurt Hutton/Picture Post/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Hutton generally used the same equipment throughout his career, trusting in his Leica and Contax with a relatively limited array of Sonnar and Elmar lenses – he generally liked to travel as light as possible. Hutton preferred to work with natural light wherever possible and therefore rarely resorted to the use of flash. He would rarely go out on a job with a premeditated shot in mind – the sum of the whole photo-essay was what really interested him – and tended to shoot intuitively, occasionally checking aperture and exposure only after he had taken the shot. What is remarkable is the consistently high technical quality of his work, which he saw as a mere detail and relatively unimportant. Compassion for his fellow man and the naturalness of composition was what mattered most to Hutton and he abhorred what he called “artificial pictures”. His job, as he saw it, was to simply produce “an objective picture of life” – capturing both the ordinary and the extraordinary – which was Picture Post’s forte.

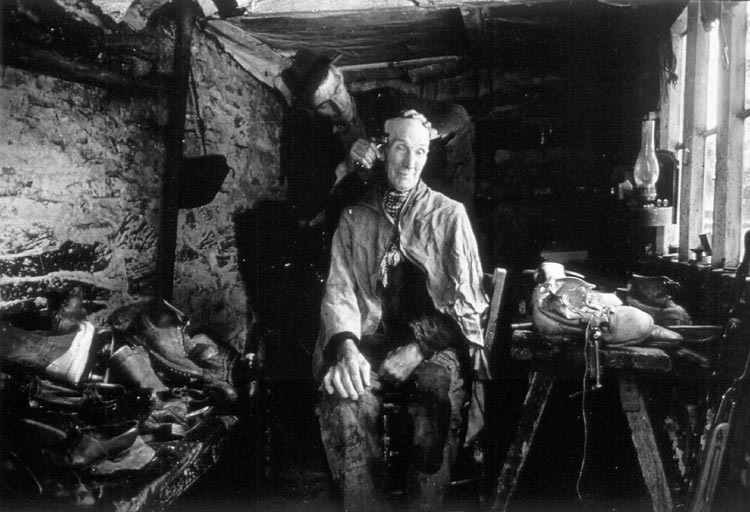

‘Old Tom’ Owen, a country hedge-layer having his hair cut by Handel Lewis. Original Publication: Picture Post – 1820 – A Man Of Hills And Rivers – pub. 1944 (Photo by Kurt Hutton/Getty Images)

During his period with the magazine, he shot over 900 photo-essays and is regarded as one of the pioneering 35mm photographers of his day in Britain. A rather shy and retiring man, Hutton was, ironically, the epitome of the English gentleman in his characteristic tweed jacket and monocle – he certainly did not look like a hardened photojournalist in the same vein as his fellow staff photographers. Yet his self-taught style of photojournalism was revered by many of his peers including Bill Brandt, his former tutor Felix Man and Bert Hardy amongst many others. In his twilight years, he moved to Aldeburgh in Suffolk and became the photographic biographer to Benjamin Britten, who, like many others, deeply respected the warm humanity and sympathetic technique that had marked Hutton’s work throughout his career. Hutton died at his Suffolk home in 1960, aged 67.

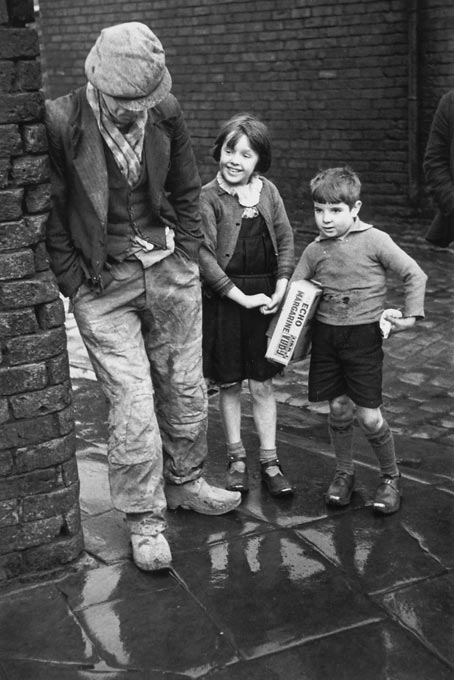

An unemployed man leaning against a wall in Wigan, with two children looking on. Original Publication: Picture Post – 228 – Wigan – pub. 1939 (Photo by Kurt Hutton/Picture Post/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

The photography of Kurt Hutton between 1938 and 1957 is a part of the Picture Post collection, contained within Hulton|Archive, a division of Getty Images Inc. Over 4,000 alternative images by Kurt Hutton can be viewed at www.gettyimages.com

Alfred Smith, one of the country’s 1,830,000 unemployed people, who draws two pounds, seven shillings and sixpence a week in unemployment benefit, Peckham, south London, January 1939. Original Publication: Picture Post – 86 – Unemployed – pub. 21st January 1939 (Photo by Kurt Hutton/Picture Post/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

9th December 1950: A couple sitting next to the stage for a floor show at ‘La Nouvelle Eve’, the newest and most expensive night spot in Paris. Original Publication: Picture Post – 5214 – Deux Jolies Anglaises – pub. 1950 (Photo by Kurt Hutton/Picture Post/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

March 1954: Children from poverty-stricken families playing at Jubilee Buildings, Wapping, a slum dwelling in east London. Original Publication: Picture Post – 6845 – The Best And Worst Of Britain (Neglected Children) – pub. 1954 (Photo by Kurt Hutton/Picture Post/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)