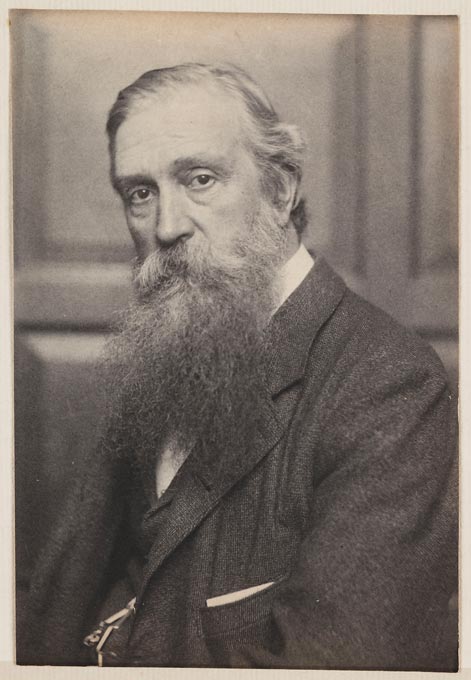

William England is arguably one of the forgotten giants of 19th century British photography and, regretfully, his work is largely overlooked today. Born in London in 1816. England began his photographic career in the early 1840s as a daguerreotypist, using both wet and dry processes and printing with albumen. After building a reputation as both a gifted technician and portrait photographer of some talent, he eventually abandoned portraiture to join The London Stereoscopic Company, upon its founding in 1854. England soon became the company’s principal photographer and leading technical innovator. England was largely responsible for building London Stereoscopic’s global reputation over the next decade and his travels took in a wide variety of foreign destinations such as Ireland (1857), the US and Canada (1858 and 1859) and Paris (1860).

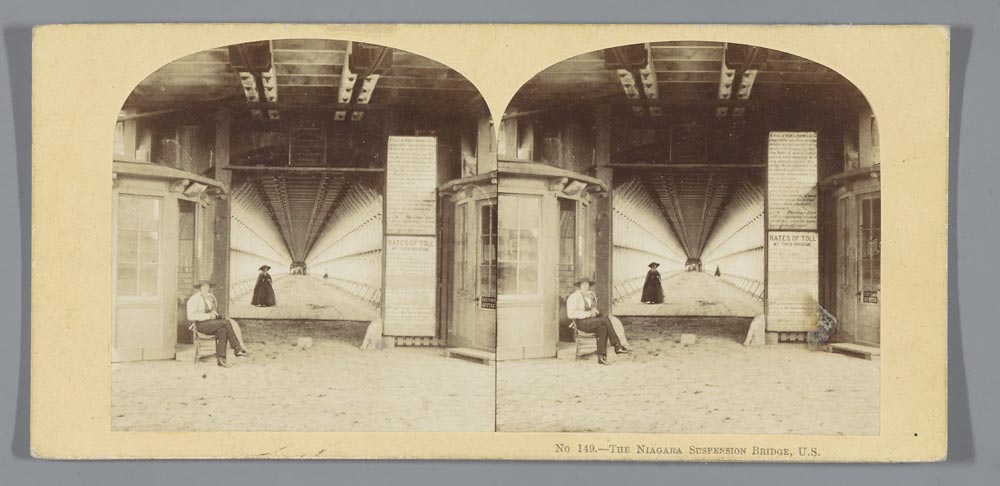

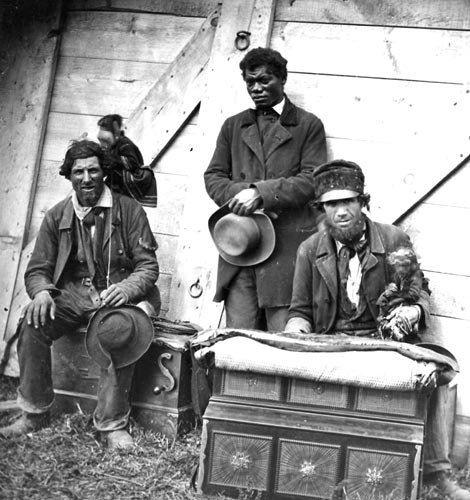

It was primarily these ‘exotic’ views that captured the imagination of the public and contributed greatly to the rapid rise of London Stereoscopic in the 1850s and 60s when stereography was at the height of its popularity. Originally founded by George Swan Nottage, The London Stereoscopic Company produced a wide variety of stereoscopic views that were all the rage during the Victorian era and London Stereoscopic were one of the very first companies to license their imagery for commercial reproduction on a global basis. Staff photographers such as Reinhold Thiele and William England travelled the world in their mobile, horse-pulled darkrooms shooting a variety of subjects and views for commercial reproduction by London Stereoscopic.

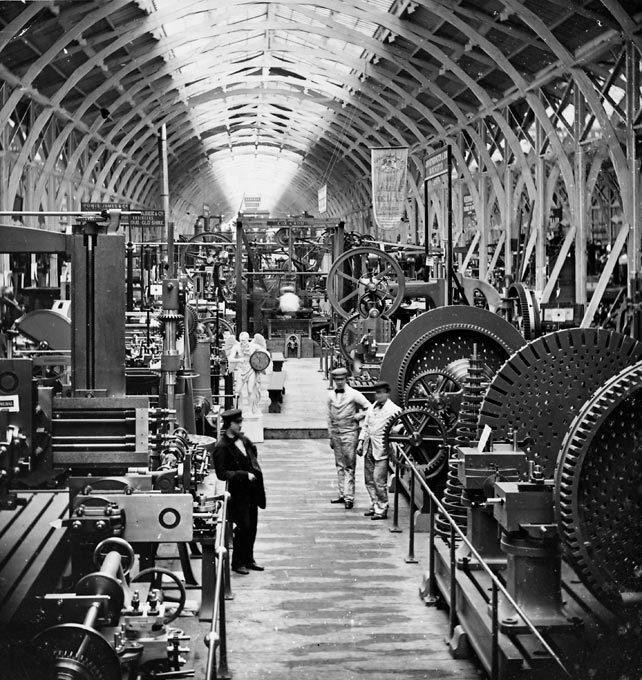

Aside from his outdoor work England produced a variety of subject matter including formal portraiture and London Stereoscopic’s renowned ‘Comic’ series’ which included the hugely popular ‘ghost’ stereographs, employing double exposure techniques. England left London Stereoscopic at the height of their popularity in 1863 to concentrate on a freelance career though his last major project on behalf of London Stereoscopic was as the exclusive photographer for the International Exhibition in London, 1862. England’s collection of some 15,000 stereoscopic plates have survived relatively intact over the years and was once ‘saved’ from being turned into greenhouse glass shortly after London Sterecoscopic ceased trading in 1910!

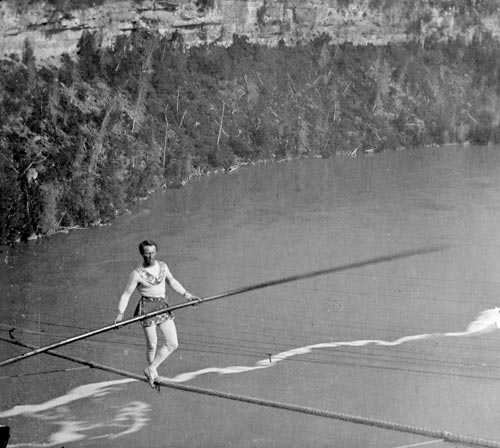

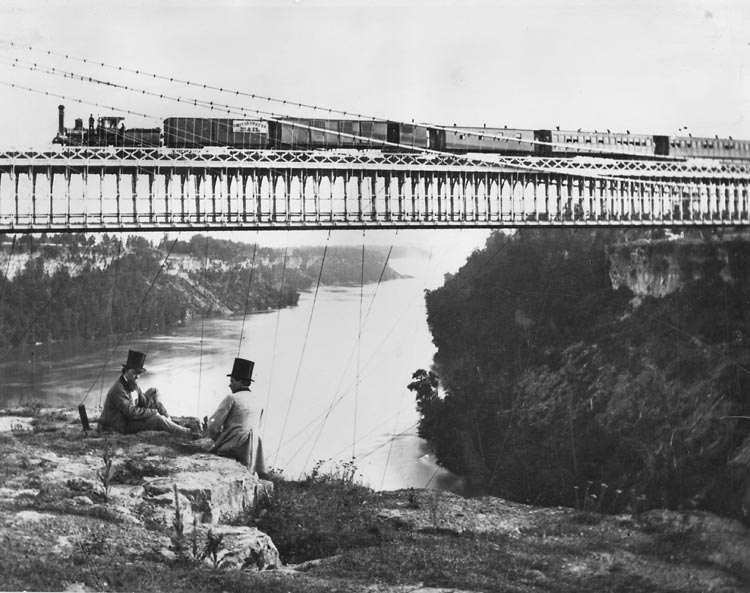

The invention of 3-D photography (stereography) first received popular acclaim at the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London and within 10 years stereographs had entered almost every home in Europe and America as a new form of entertainment. England pioneered the ‘focal plane shutter’ camera which greatly improved image clarity which, in turn, revolutionised the popularity of the stereograph. He later developed a photographic device with variable shutter openings, in essence the forerunner to the modern SLR camera. England’s memorable view of Blondin crossing Niagara Falls on tightrope in 1859 became one of the best-selling stereographs of all time – allegedly selling some 100,000 copies worldwide.

The majority of England’s stereo views were taken on a single short focus lens ‘pocket’ stereoscopic camera which was introduced by London Stereoscopic in 1858. The entire apparatus was a mere 20cm long x 12 cm wide x 5cm deep and, weighing in at just over half a kilogramme, meant it was eminently mobile and suited England’s travels perfectly. The only problem with this type of single lens design was the fact the whole camera needed to be laterally moved along a groove or track, after the first image had been taken on one half of the plate. Though the camera movement could be varied up to a distance of 33cm, scientists of the day advised this not to be any more than the distance between the pupils of the eyes – about 6cm – for the proper stereo effect to be achieved. The single lens camera was soon superseded by the development of the ‘binocular’ or twin lens camera which took both images simultaneously which significantly accelerated the picture taking process.

As well as being a fine photographer with an instinct for style and composition, England was also a great technician and a number of London Stereoscopic’s developments in photographic apparatus – particularly those connected with stereography – were largely due to England’s technical expertise. After leaving London Stereoscopic in 1863 to pursue a freelance career, England continued with his stereo work, capturing views all over Europe; France, Switzerland and Italy in particular. The many Alpine views taken by England were considered to be some of his finest and were very much his forte, those taken of the Chamonix Glacier being particularly sought after and the resulting stereographs sold all over the continent as well as in Britain.

In 1867 England erected a photographic studio based in Notting Hill, London ostensibly to print from his landscape negatives but continued to travel throughout Europe, which occasionally led him into difficult situations. During the Franco-German war of 1870, he was arrested in the Rhine region of Germany and accused of being a French spy. England was eventually released but not before the authorities had initially confiscated his lenses, though these were later returned. England continued to travel to his beloved mountains for the next 30 years adding new images to his growing collection each summer. At his peak, England was regarded as one of the leading landscape photographers in Europe. England is perhaps one of an elite band of photographers who spanned the whole evolution of photography from the daguerreotype to the roll-film and seemingly adapted to each phase with relative ease. Throughout his career, his advice and patronage were much sought after. He became President of the London Photographic Society in 1886 and was also a member of the Council of the Royal Photographic Society for many years. England died in August 1896, at the age of 80 and is arguably the greatest of a number of unsung British photographers of the Victorian era.

A great proportion of England’s work – the views taken on behalf of London Stereoscopic – are currently in private hands, owned by Getty Images, and housed in east London. Together with the stereoscopic negative plates, the collection also includes the original day books, contact prints and catalogues. Taken as a whole, the collection constitutes an invaluable photographic document of the period – not only for their historical significance but also for their image clarity, striking detail and technical brilliance. A unique view of the Victorian era…and all in glorious stereo.