“Mad Romantic” is a term often used in the literature to describe the biographical journey of the extravagant John J. McKendry. Born in 1933 in Canada, McKendry was the Curator of Prints and Photographs at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York from 1967 until his brutal death in 1975. Talking about John J. McKendry, Maria Morris Hambourg, a former Curator in Charge of the Department of Photographs at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, points out:

“Dressed in velvet suits, John [McKendry] lived the high life. He was a downtown, uptown, all-around-town fellow who could party half the night and still manage his responsibilities running the department at the Met. He and Robert Mapplethorpe were close.”1Interview with the author, published in History of the ‘Eye Club’. The values of photography. Paris-New York, 1960-1989, PhD dissertation, University Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, 2020, p. 224.1

Known for his dandy like style — dressed with silk shirts and silver rings on every finger — McKendry’s personality was alternately compared to one of Peter Pan’s Lost Boys by artist Patti Smith in her book Just Kids2Patti Smith, Just Kids, Gallimard, 2013, p. 267 and to the “Mad Hatter’s” in Alice in Wonderland by Patricia Morrisroe, Robert Mapplethorpe’s (1946-1989) biographer.3Patricia Morrisroe, Mapplethorpe, a biography, Da Capo Press, 1995, p. 97 Due to his friendship and affair with Mapplethorpe in the early 1970s, McKendry’s name is always but briefly mentioned in almost all publications on the artist. The two men met in 1971 when Mapplethorpe was twenty-five years old and living at the Chelsea Hotel with Patti Smith. At that time, the artist was making collages and Polaroids that had never been exhibited. Two years before he met Sam Wagstaff (1921-1987)4Philip Gefter, Wagstaff : Before and After Mapplethorpe – A Biography, Liveright, 2014.4 — another and more important supporter of Robert Mapplethorpe — McKendry was one of the first art professionals who helped the artist to connect with the “Art World”5Howard S. Becker, Art Worlds, University of California Press, 1984, introducing him to various networks including the New York high society he himself was part of. John J. McKendry was indeed one of the historians and curators of the 1970s who crafted the link between artists, the first photography departments in New York museums and the growing interest in photography by Andy Warhol’s (1928-1987) circle.

John J. McKendry came from a Communist Catholic family originally from Ireland. He graduated from the University of Alberta in 1958 and then from the Institute of Fine Arts in New York in 1961. In 1962, he became the Met’s Department of Prints Curatorial Associate and then, from 1967, he was put in charge of the Department of Prints and Photographs. But McKendry’s curatorial work began to attract attention with his 1964 exhibition Aesop, Five Centuries of Illustrated Fables which presented a panorama of illustrations of the famous stories that inspired many authors and artists, from Gustave Doré (1832-1883) to Alexander Calder (1898-1976)6John J. McKendry, Aesop : five centuries of illustrated fables, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1964. As a curator, McKendry had a trans-historic practice. Interviewed by Ruth Bowen for the radio show Views on Art he stated: “My favorite period in printmaking is from the 15th to the 20th century!”7Ruth Bowen talks with John J. McKendry, Associate Curator of Prints at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, February 21st 1968, part of Views on Art, The NYPR Archive Collections [online]

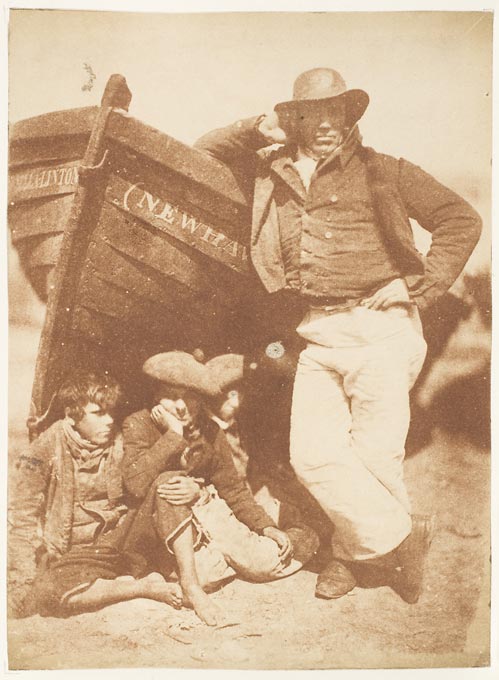

During the 1960s, he was one of the many art world people who traveled across the Atlantic. He went to Paris and London to acquire prints, etchings, rare books, architectural drawings and old photographs from booksellers and dealers. In 1967, McKendry was noted for his book Four Victorian Photographers, which reflected his active interest in Europe’s nineteenth century.8John J. McKendry, Four Victorian photographers, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1967 At a time when books about the history of photography were rare, this small-format book with high-quality reproductions was one of the first to show a wide selection of photographs by Adolphe Braun (1812-1877), Julia Margaret Cameron (1815-1879), David Octavius Hill (1802-1870) & Robert Adamson (1821-1848), and Thomas Eakins (1844-1916).

In charge of prints and photographs acquisitions for the Met, he explained in the same radio program:

“I think that any person of any age who wants to collect today […] can learn with prints and illustrated books because theycan afford to make mistakes, and they can’t in most any other fields of collecting. You really can build up an interesting collection of prints and learn so much because there is such an extraordinary broad of things available in the city.”9Ruth Bowen talks with John J. McKendry, Associate Curator of Prints at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, February 21st 1968, part of Views on Art, The NYPR Archive Collections [online]

In this 1968 interview he also commented: “I go to dealers in town a lot and then I go to Europe, London is the great spot.”10Ruth Bowen talks with John J. McKendry, Associate Curator of Prints at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, February 21st 1968, part of Views on Art, The NYPR Archive Collections [online] While the names of European booksellers and dealers in McKendry’s circles are not mentioned in this program, a letter kept in the Aperture archives mentions the name of André Jammes’ 1971 exhibition of photographs, French Primitive Photography.11Letter from John J. McKendry to Michael Hoffman, July 22nd 1969, Aperture Foundation Archives, Aperture Foundation, New York This exhibition held at the Philadelphia Museum unveiled the collection of the French bookseller and historian to the American public. Organized at the initiative of Minor White (1908-1976) and accompanied by a catalog published by Aperture,12André Jammes & Robert Sobieszek, French Primitive Photography, [published on the occasion of the exhibition at the Albert Stieglitz Center of the Philadelphia Museum of Art from November 17th to December 28th, 1969 with an introduction by Minor White], Aperture, 1969 it was one of the first exhibitions in the United States to present photographs by Maxime Du Camp (1822-1894) and Gaspard-Félix Tournachon, known by the pseudonym Nadar (1820-1910). McKendry, who was himself keenly interested in French literature and especially in poems by Arthur Rimbaud (1854-1891) showed curiosity in the exhibition. The transatlantic round trips and his interest for European photography illustrate the establishment of an international network in the photography world.

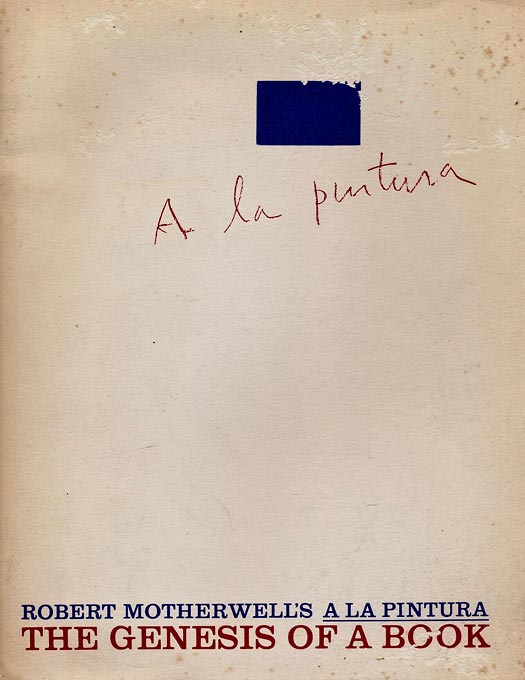

On the personal side, McKendry got married in 1967 to Maxime de la Falaise (1922-2009), a model, socialite and food editor at Vogue. She was the daughter of portrait painter Sir Oswald Birley (1880-1952) and former wife of Count Alain Le Bailly de La Falaise (1905-1977) with whom she already had two children, Alexis (1948-2004) and Loulou de la Falaise (1947-2011), one of Yves Saint-Laurent’s (1936-2008) fashion designers. In their apartment near Central Park, McKendry and his wife hosted social gatherings and festive dinners, where New York high society and artists met. McKendry was also interested in the art of his time, and contributed to the Met’s landmark 1969 exhibition New York Painting and Sculpture: 1940-1970, organized by Henry Geldzahler (1935-1994). A catalog was published with texts by critics such as Michael Fried, Harold Rosenberg (1906-1978), Robert Rosenblum (1927-2006), William Rubin (1927-2006) and Clement Greenberg (1909-1994).13Henry Geldzahler, New York painting and sculpture: 1940-1970, foreword by Thomas P.F. Hoving, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1969 On this occasion, the American photographer Bruce Davidson, commissioned by the Magnum agency, produced a behind-the-scene photographic report on the organization of the exhibition. About ten images show McKendry hanging the artworks or looking closely at the details of engravings and prints. Likewise, he also promoted the work of contemporary artists such as Helen Frankenthaler14Helen Frankenthaler: Sixty-two Painted Book Covers, [catalogue by John J. McKendry], the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1973 (1928-2011) and Robert Motherwell (1915-1991). He contributed to the publication of Motherwell’s book A la Pintura: the genesis of a book which underlined his active interest in the relations between Contemporary Art, publishing and engraving.15Robert Motherwell’s A la pintura : the genesis of a book, [exhibition and catalogue prepared by John J. McKendry] ; texts by Robert Motherwell and Diane Kelder, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1972

McKendry through the lens of Mapplethorpe

As a supporter of Mapplethorpe’s practice, McKendry is known for having gifted the artist a Polaroid camera16The artist and filmmaker Sandy Daley gave Mapplethorpe his first Polaroid camera while they were living in the Chelsea Hotel and for helping him to earn a commission from the Polaroid Corporation, which sponsored an Artist Support Program. In the early 1970s, he began to produce numerous series of nudes, flowers, sculptures, self-portraits and portraits. He went to London with McKendry, who introduced him to authors like Derek Jarman (1942-1994) — who a few years later directed Sebastiane (1976), which marked the history of Queer culture — and members of the British aristocracy. The curator’s influence on the artist seems to have also impacted him in his practice as an artist-collector. From about 1974 to 1978, Mapplethorpe traveled frequently to London for the Sotheby’s photography auctions. At that time, he bought several portraits by Julia Margaret Cameron which he hung in his studio.17Hélène Pinet in Jérôme Neutres, Robert Mapplethorpe, Réunion des Musées Nationaux, Paris, 2014, p. 249 In Cameron’s photographs, models and relatives take turns posing behind the photographer’s lens. It is interesting to note that many of Mapplethorpe’s photographs resonate with Cameron’s style. For example, in 1979, he took the portrait of the young Ariel Philipps, standing in profile in front of a neutral background that evokes — both in the facial features and in the pose and staging — the portrait of Adeline Norman taken in 1874 by Julia Margaret Cameron. Interviewed by Edith Cottrell in 1978, Mapplethorpe stated: “ The process that I am using is a way of taking pictures that was done even in Victorian times. It’s rather old-fashioned but at the same time, I am using Polaroid which is completely contemporary.”18This interview conducted by Edith Cottrell is published in 1999 in Art Press, n°242, p. 36-39. It is also quoted in Robert Mapplethorpe, Museu de Arte Contemporanea de Serralves, 2018, p. 300 It is noteworthy that Mapplethorpe’s first successful exhibition in 1973 at LIGHT Gallery in New York City showcased his Polaroid practice.19Sylvia Wolf, Polaroids-Mapplethorpe, Whitney Museum of American Art, Prestel, 2008, p. 54

In parallel, John J. McKendry’s health deteriorated and those close to him would say that he suffered from alcoholism and depression. He died at the age of 42 in June 1975, leaving behind him many mysteries. Some say that he was one of the first to die of AIDS and others say that it was a liver illness. The day before he died, Robert Mapplethorpe took a portrait of him in his room at Saint Clare’s hospital in New York with his new Hasselblad camera. The image shows McKendry’s face cropped so that only half of his face is visible, next to an electrical outlet, coated with jelly moisturizer, his eye raised to the sky, his melancholic gaze revealing that he was already somehow slipping away.20Patricia Morrisroe, Mapplethorpe, a biography, Da Capo Press, 1995, p. 150-153 This portrait is reminiscent of American photographer Peter Hujar’s (1934-1987) picture of American transgender, actress and Warhol superstar Candy Darling (1944-1974) on her deathbed. As Dimitri Levas, the vice-president of the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation, notes while being interviewed : “It seemed that John J. McKendry was pulling the plug”,21Judith Benhamou-Huet, Mapplethorpe, vivant – réponses à des questions, Les Presses du Réel, 2014, p. 94 as if to trigger his death more quickly.

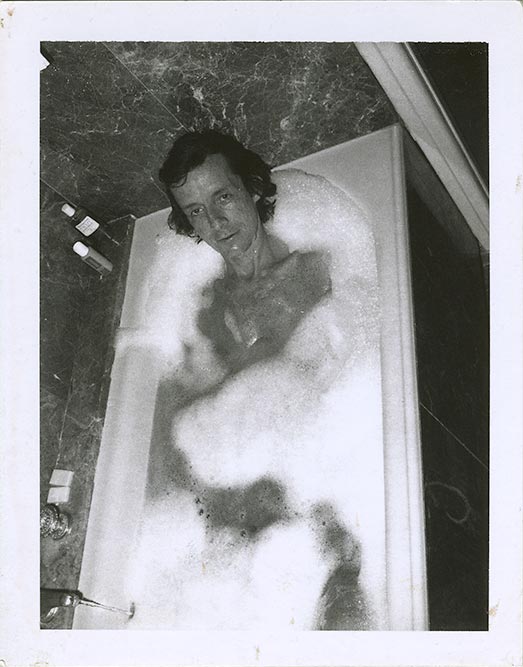

Writings on Mapplethorpe point out that McKendry played a significant role in the artist’s career. On the one hand, he was one of the many people who helped Mapplethorpe gain recognition from his peers and collectors, two of the conditions for an artist to be “successful”, in the words of American sociologist Alan Bowness.22Alan Bowness, Les Conditions du succès, Allia, 2011, p. 12-13 They also put forward the fact that the artist insisted that the curator collect more photography at the Met. In retrospect, it seems that the two men had an influence on each other. In any case, Mapplethorpe’s relationship with John McKendry was decisive, as were his visits to the Met’s photographic storerooms, which hold many photographs by Julia Margaret-Cameron and Alfred Stieglitz’s (1864-1946) personal collection of photographs. Looking at the prints, he gained knowledge in the history of photography, the beauty of the craft and the art of portraiture. As art historian Sylvia Wolf notes, Mapplethorpe’s Polaroids from the 1970-1975 period echo the portraits made by Alfred Stieglitz of his wife Georgia O’Keeffe (1887-1986) a series kept in the Met’s collections, which the artist discovered with John J. McKendry in the museum’s storage rooms. On the other hand, four staged portraits of McKendry by Mapplethorpe reveal the intimacy of a photo shooting: McKendry is dressed elegantly in front of a neutral background, and Mapplethorpe made two portraits of his face and two others centered on his folded hands. The several Polaroids of McKendry by Mapplethorpe that have yet to be published seem to be made both in an aesthetic research and in a desire to show the artist’s intimacy, as shown in Mapplethorpe’s 1971 portrait of McKendry in his bubble bath.

General bibliography

Howard S. Becker, Art Worlds, University of California Press, 1984.

Judith Benhamou-Huet, Mapplethorpe, vivant – réponses à des questions, Les Presses du Réel, 2014

Judith Benhamou-Huet, Dans la vie noire et blanche de Robert Mapplethorpe, Grasset, 2014

Alan Bowness, Les Conditions du succès, Allia, 2011

Philip Gefter, Wagstaff : Before and After Mapplethorpe – A Biography, Liveright, 2014

Henry Geldzahler, New York painting and sculpture: 1940-1970, foreword by Thomas P.F. Hoving, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1969

Path Hackett, Andy Warhol, The Andy Warhol Diaries, Grand Central Publishing, 1991

Patricia Morrisroe, Mapplethorpe, a biography, Da Capo Press, 1995

Patti Smith, Just Kids, Gallimard, 2013

Sylvia Wolf, Polaroids-Mapplethorpe, Whitney Museum of American Art, Prestel, 2008

Robert Mapplethorpe, Museu de Arte Contemporanea de Serralves, 2018

Articles

Christopher Petkanas, “Lady Libertine”, The New York Times Style Magazine, August 18th 2010

“John McKendry, Met curator, 42”, The New York Times, June 25th 1975

“New Again: Patti Smith” by Maxime de La Falaise, Interview Magazine, February 1976

“When Robert Mapplethorpe Took New York” by Bob Colacello, Vanity Fair, March 2016

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank James Crump, Maria Morris Hambourg and Weston Naef for sharing their knowledge on the subject. I would also like to express my gratitude to the Aperture Foundation Archive, Monica McTighe (Dedalus Foundation), Sarah Haug (Helen Frankenthaler Foundation) Matthew Murphy (Magnum Photos New York), Melissa Bowling and Meredith Reiss (the Metropolitan Museum of Art), Maria Murguia (the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts) for their help. My sincere thanks go to Joree Adilman and Dimitri Levas (the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation) for their continuing support and for sharing unpublished Polaroids of Robert Mapplethorpe.

Isabella Seniuta received her PhD in Art History at the University Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne in 2020. She currently teaches a MA seminar at the Sorbonne on the History of Collections. Her research interests include Sociology of Art, the History of the Photography Market and Queer studies.