As I understand it, with some of the killed Picture Post stories there were only negatives and prints. With others, there were “galleys”, or mock-ups. How many extant galleys were there?

– The “killed” boxes contain folders of prints, with correspondence, handwritten captions and in some instances, there are also galleys, so we’re not sure how many there are just yet. Unearthing materials like these in the Hulton Archive is not uncommon – the racks are full of unseen treasure – but the process of identifying and cataloguing the materials we find is an ongoing process. Over the next few years, we will be sifting through the twelve boxes worth of folders covering the years 1946 to 1957, alongside other conservation and digitization projects relating to the 1500 collections we manage.

What sort of condition were the galleys in? And was the condition pretty uniform?

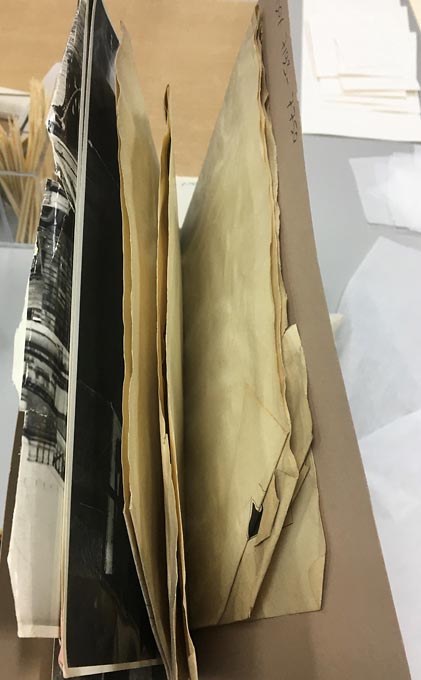

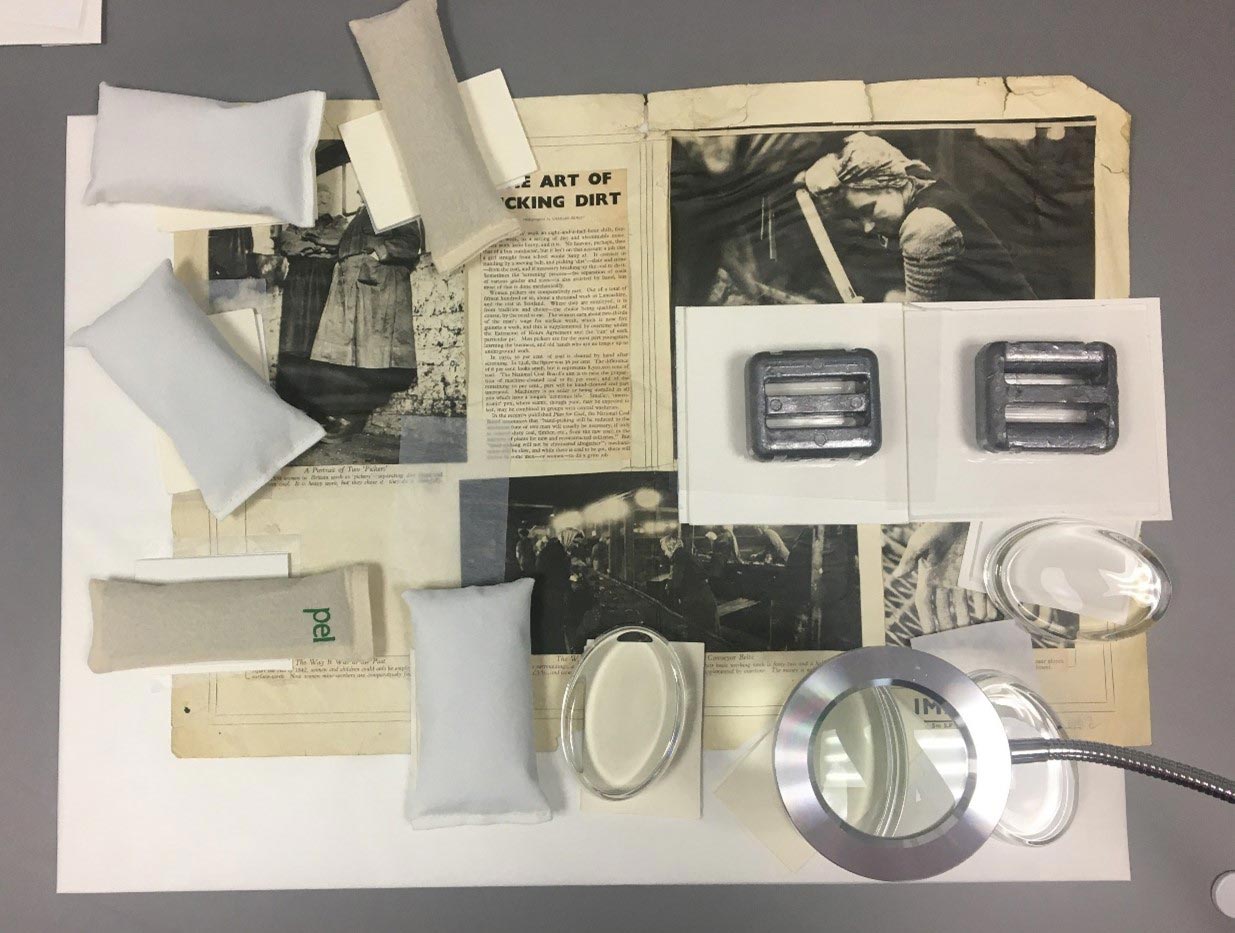

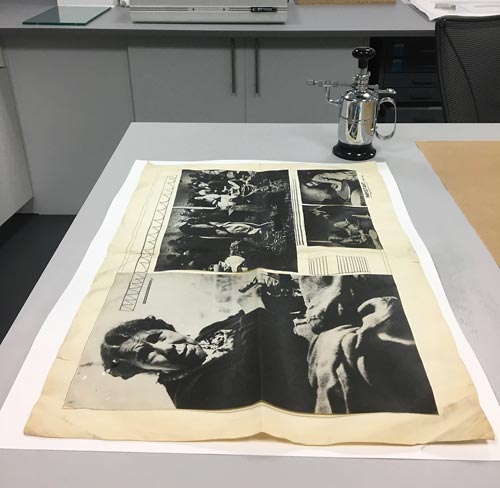

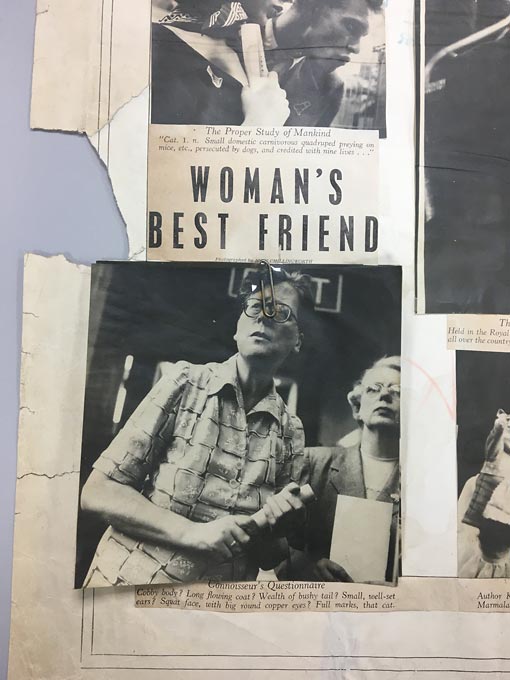

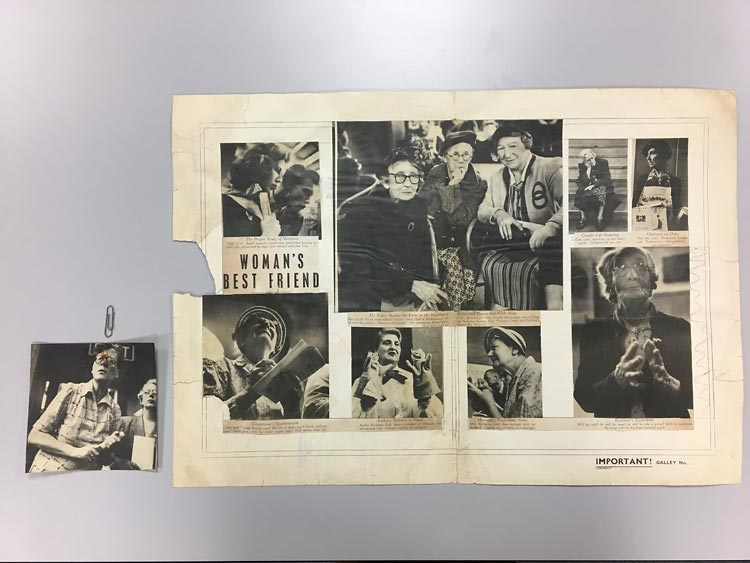

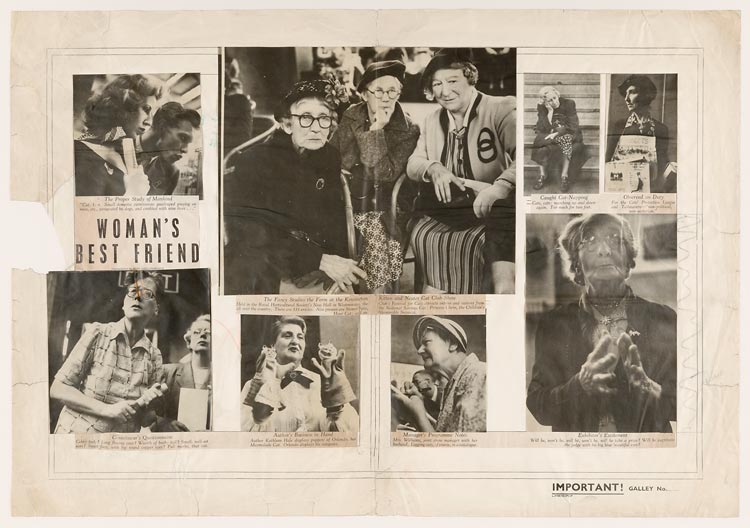

– As you can see, the galleys were page layouts for publication. The stories were written, titled, had images attached and were all set to go to print when they were “killed”. It seems the unused Galleys were simply folded or rolled up and squashed in with the A4 files, this may have been at any point in the last 70 odd years, irrespective of how that would damage the photographic materials physically mounted on the sheets. The ones that made it to the conservation bench were torn, fractured and folded, some were in a very bad way, and some were in pieces. Several of them were stuck together. Gelatin silver prints pressed tightly together will “block”, stick to each other when the EMC in the materials rises, and a few had rusty paperclips attaching more than one photograph on top of each other so the editor could choose the final version. They are great examples of graphic design and publishing methods used in the pre-digital era.

What were the first steps in the conservation process?

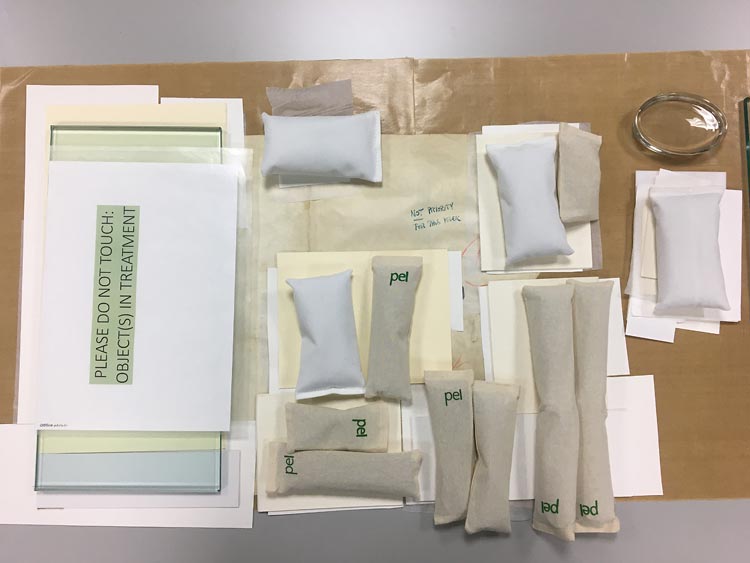

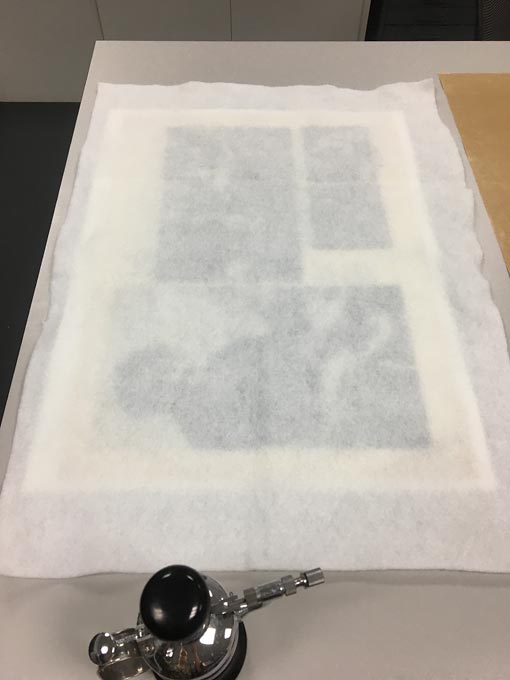

– The first steps in any conservation treatment are to photograph it, record the damage, which may look very different when flattened, and then dry clean all the surfaces. You have to remove the dirt, dust, and debris so that it doesn’t sink into the paper fibres and print surfaces during treatment, not just because it will look horrible in the repairs but because it will interfere with the adhesion of the materials. I used soft brushes, hand air bellows, cotton wool and dry sponges to dry clean them in the physical state they were in, as best I could without exacerbating the damage, and then I humidified them, to flatten them out and work on the stabilisation and repairs.

Materials have a physical memory, so the galleys needed coaxing and reconditioning to relax back down flat. Flat-ish; the stresses and strains held in a crumpled and folded structure rarely dissipate entirely. Aqueous (here humification) treatment prevents further damage to brittle fibres, fractures, folds, and areas where materials have been rolled up or compressed. The galleys were therefore gently misted with distilled water, recto and verso, and placed between blotter, silicon release and polyester capillary matting. The open-fibred matting slowed the drying process down beautifully and also brought a gentle weight to bear, encouraging the materials to flatten out. This form of aqueous treatment is a perfect way to control the delivery of humidity into the materials; they are not wetted, but their equilibrium moisture content (EMC) is raised enough to expand the materials sufficiently to flatten & repair them. I then cleaned again where necessary, wet cleaned the photographic prints using a solution of ethanol and distilled water, stabilised them on the mounts, repaired the tears and supported the losses using Japanese tissue and wheat starch (easily reversible in the event the treatments need to be removed or redone in the future).

How many galleys have you treated so far?

– I think I have done about fifteen so far, but there will be many more and I really enjoy working on them- they are so deliciously complex to treat. I love the challenge. This sort of work takes time, you can’t just fix it all in one go. The materials that make up each galley are physically and chemically different from each other and so react differently to the treatments performed and to their environment. The stabilisation of them is a gently staged process. Each treatment is bespoke. It takes weeks, not days or hours.

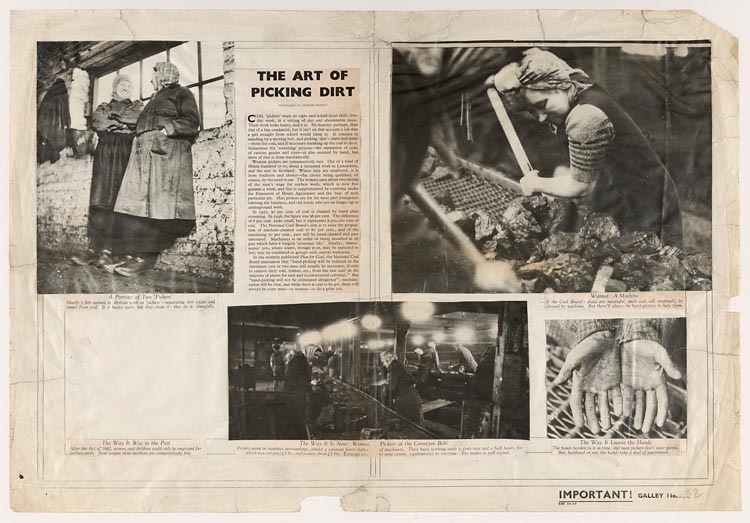

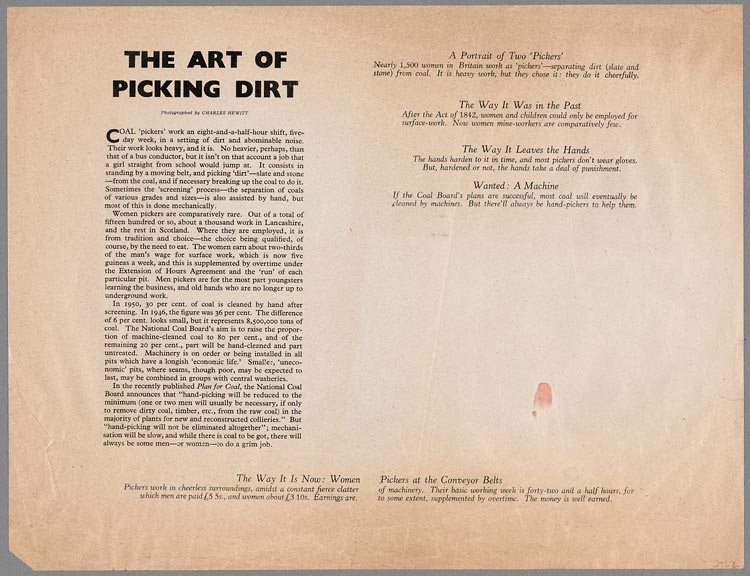

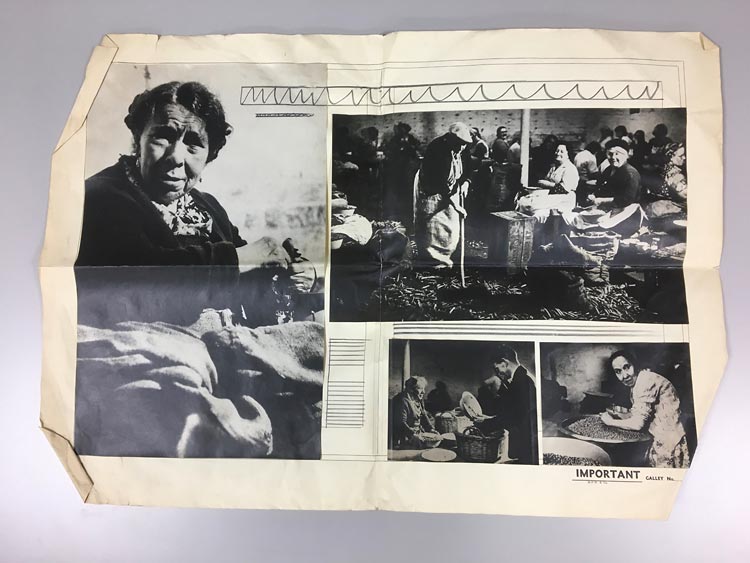

Can you comment on the Lady Coalminers (The Art of Picking Dirt/Women Still Work in the Coal Mines), the Tea Pickers (Pea Shellers at Covent Garden) and Woman’s Best Friend?

– The Last job on earth and Women still work in the coal mines galleys Nos. 1&2 and 1-2 (Picture Post killed story 5420) were in very poor condition. There was substantial mechanical damage, loss and tears to the edges and prints, and damage to the paper surfaces where mounted materials had been torn off the galley surfaces. Galley 1&2 was very dirty and badly stained (additionally had large red stain lines across the centre on the verso). Galley 1-2 had only the title and one mounted image remaining (with a paperclip attached but no second image over it). The paperclip was damaging the surface of the print but still part of the history of the piece, so it was carefully removed, cleaned, and stabilised with the rest and returned to its position on the print surface with a small section of thin Mylar which protected the two materials, front and back, from each other. Both galleys were repaired and stabilised, and where the paper fibres had suffered stress, deformation and strain, the vulnerable fibres were consolidated with wheat starch paste, to give them cohesive strength.

The Pea Shellers galleys Nos. 1 & 2, and 3, (Picture Post killed story 7313), are in quite good condition considering, a few tears and folds in the paper edges and the mounted prints with sections of silver mirroring and image loss across the centre folds. Maybe these were “killed” early as although six images are mounted, the title, captions and text have not yet been attached. There is a pink circle around the words SWEAR BAG on the wall in the image on Galley 3 marked “hold” which has stained the opposite half of the page where it was folded. It is these kind of associated issues – solubility of this ink- that a conservator must also consider when planning treatments.

The Women’s best friend Galleys Nos. 1&2, and 3 (Picture Post Killed story 6197) were in poor condition, very dirty, stained, torn, fractured with substantial losses (some of which were found separately at the bottom of the folder). It appears complete and seems ready to go, with all the imagery (again two options provided for one image space), titles, text and captions yet marked “NOT PRIORITY FOR THIS WEEK” on the verso in slightly smudged blue ink. This galley (1&2), with obviously fugitive inks, multiple tears, fractures, losses and two versions of prints held with the paperclip was a challenge to conserve!

Image & Reality are publishing some of the killed stories in a forthcoming book. Will Getty Images make the rest available on the website?

– The galleys may not be of wider commercial use in terms of licensing, but they certainly add context to images already scanned from the Picture Post negatives over the years (which have been our only content source for killed stories until now), and that extra detail can add real value for Getty Images customers. As objects of historical interest, our curator is also planning to make them publicly available to support academic research.