The San Francisco Museum of Art1The author would like to thank the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art Archives for kindly allowing the publication of the cited archival material and photographs, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art Copyright team for licensing the reproductions of the two works in the Museum’s collection, and Katherine Bunnell for granting permission to publish Peter Stackpole’s work. Special thanks are due to Peggy Tran-Le at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art Archives for the invaluable, sustained assistance in this research project and the Faculty of Arts and Creative Industries at the University of Sunderland that generously funded the field research and supported the writing of this article. opened its doors on the top floor of the War Memorial Veterans Building in 1935. A year later, in October 1936, its first Director, Dr. Grace McCann Morley, would write to the Resettlement Administration in Washington D.C. being “anxious” to stage an exhibition of Miss Dorothea Lange’s photographs that were produced only the year before in the context of the Farm Security Administration project.2Grace McCann Morley to Roy Stryker, 31 October 1936, 1936 Artist’s Correspondence, Office of the Director 1935–1956, Administrative Records, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art Archives.

Morley was admittedly a museum director extraordinaire.[Fig.1] During the twenty-four years of her directorship, the San Francisco Museum of Art, not only grew its collection and exhibition and education programs despite limited funding and wartime hardships. It also became a leading advocate for modern art on the isolated West Coast. A great believer in the social value of contemporary art and advocate of cultural democracy, Morley argued that the prime function of museums was “to help as broad and as large a public possible to understand, appreciate, and use of art of its own time”.3Morley cited in Kara Kirk, “Grace McCann Morley and the Modern Museum,” in San Francisco Museum of Modern Art: 75 Years of Looking Forward, ed. Janet Bishop, Corey Keller, and Sarah Roberts (San Francisco: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 2009), 71. True to her words, the director sought to open the Museum to different publics as well as contemporary artists of every feather, also accommodating new media, such as photography and film, to embrace the cutting edge of creative practice. Morley expanded the field of modern art to include work from Latin America and gave female artists a voice in the American art museum with forty solo exhibitions organized in the first five years of her tenure alone.4For an excellent analysis of Morley’s efforts to diversify modern art, see Berit Potter, “Grace McCann Morley: Defending and Diversifying Modern Art,” San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, June 2017, https://www.sfmoma.org/essay/grace-mccann-morley-defending-and-diversifying-modern-art/ [last accessed 20 May 2021]. For Morley’s role as a state liaison for inter-American affairs between 1941 and 1945, see Grace L. McCann Morley, “Art, Artists, Museums, and the San Francisco Museum of Art,” interview by Suzanna B. Riess, 1960, 43, Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, https://digicoll.lib.berkeley.edu/record/217123?ln=en [last accessed 20 May 2021].

This article explores Morley’s contribution to the institutionalization of photography in the art museum, which in 1930s North America was still a male-dominated field.

Grace Morley was born in Berkeley in 1900 but was raised in the small town of St. Helena in Napa County, north of San Francisco. Being ill as a child Morley did not attend school until she was ten years old, but this did not stop teenage Morley from teaching herself French with the aid of a dictionary and a reader to an advanced level. A few years later, Morley would major in French and Greek as a postgraduate student at the University of California, Berkeley and gain a fellowship at Sorbonne in Paris to pursue doctorate studies in art and literature, which she completed in 1926. It was in Paris that Morley would have her first encounter with old masters and European avant-garde practices in and outside museums. Yet, curation was not something that she could aspire to. At the time, highly educated girls were destined to go into teaching and that’s what Morley did upon her return to the US, working originally as an instructor in French for Goucher College in Baltimore.5Grace L. McCann Morley, “Art, Artists, Museums, and the San Francisco Museum of Art,” interview by Suzanna B. Riess, 1960, 9–13, Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, https://digicoll.lib.berkeley.edu/record/217123?ln=en [last accessed 20 May 2021]. It was in 1929 while Morley was working at Goucher College that she was offered the opportunity to take a summer course for teachers at Harvard. There she became familiar with the curatorial work at the Fogg Museum and Professor Paul J. Sach’s famous course for training museum people that was instrumental in reorganizing American museums in the 1930s.6For an analysis of Sach’s impact on museum practice in North America, see Sally Ann Duncan and Andrew McClellan, The Art of Curating: Paul J. Sachs and the Museum Course (Los Angeles: The Getty Research Institute, 2018). This experience opened up new professional pathways for the young scholar as Morley began to entertain the possibility of working in a museum.7Grace Morley, “Oral history interview with Grace Morley,” 6 February to 24 March 1982, unpaginated transcript, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-grace-morley-12774#transcript [last accessed 20 May 2021].

In the early twentieth-century, upper-middle-class women often volunteered in museums while a number of women of means were involved in the founding of modern museums as benefactors and collectors.8Susan Armitage, Introduction to Women and Museums: A Comprehensive Guide, ed. Victor J. Danilov (Lanham, MD: Altamira, 2005), 1–10. Even so, women working in museums would often become supporters of male work, in what was long considered an “old boys’ club”, lacking men’s authority to pursue leadership jobs.9See Kendall Taylor, “Pioneering Efforts of Early Museum Women,” in Gender Perspectives: Essays on Women in Museums, ed. Jane R. Glaser and Artemis A. Zenetou (Washington/London: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1994). For instance, Abby Rockefeller, Lizzie P. Bliss, and Mary Quinn Sullivan who were the instigators of and fund-raisers for the Museum of Modern Art in New York recruited Anson Conger Goodyear to become the President of the Museum and the aspiring young Alfred Barr, Jr., as its first Director. It was quite rare in the early twentieth century to find women museum directors, like Laura M. Bragg at Charleston Museum and Beatrice Winser who directed the Newark Public Library and the Newark Museum. And those women who did get the job were, like Morley, considerably worse off when compared with their male counterparts. It is telling that Morley’s salary as museum director in 1935 was US$ 2,400, almost half of the salary of a conservator at Fogg Museum. When Alfred Barr, Jr. was appointed as the Director of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York, in 1929, he had a starting salary of US$ 10,000, as did Walter Siple when he took over the directorship of the Cincinnati Art Museum the year after.10Figures provided in Sally Ann Duncan and Andrew McClellan, The Art of Curating: Paul J. Sachs and the Museum Course (Los Angeles: The Getty Research Institute, 2018), 251–2.

Morley was offered her first curatorial post by Siple at the Cincinnati Art Museum, while she was attending his summer course for art instructors at Harvard. The Cincinnati Art Museum was a general art museum showcasing old masters, decorative arts, and ancient artifacts from the Americas. During its rebranding and expansion in the 1930s particular emphasis was paid on education with educational activities for the public and an innovative program of Saturday classes for kids to build the museumgoers of tomorrow. Morley remembered that

there was a great struggle between the educators and the curators in the museums because the curators usually liked to remain in a little tower and study, and the educators […] were the link between the eager, uninstructed general public and the specialized knowledge of the curators.11Grace L. McCann Morley, “Art, Artists, Museums, and the San Francisco Museum of Art,” interview by Suzanna B. Riess, 1960, 21, Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, https://digicoll.lib.berkeley.edu/record/217123?ln=en [last accessed 20 May 2021].

Being involved in museum activities across the board as a general curator in Cincinnati—from exhibitions, and collection building to giving public lectures and tours—Morley would be well-positioned to apply for the head curator’s job at the new San Francisco Museum of Art in 1934.

Unlike the M. H. de Young Memorial Museum and the California Place of the Legion of Honor that were city museums, the San Francisco Museum of Art was a private institution, the initiative of the San Francisco Art Association. Established in 1871, this collective of Bay-area artists occupied the premises of the Fine Arts Palace after the end of the grand Panama-Pacific International Exposition of 1915. The San Francisco Museum of Art was borne out of this initiative and was branded as a separate institution in 1921. Through fundraising efforts and partnering with the Musical Association of San Francisco and different veterans’ organizations, it was possible for the Museum to find a new home in the two granite, purpose-build Beaux-Arts buildings that were to house the new Opera House and the veteran groups together with the Museum around a memorial court.12For the early history of the San Francisco Museum of Art, see Teresa M. Tauchi, “SFMOMA: 60 Years,” in The Making of a Modern Museum, ed. Kara Kirk (San Francisco: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 1994), 36–53.[Fig. 2]

The San Francisco Museum of Art had a good art library but no actual collection apart from 98 modern French prints. It received a small annual grant from the city, earmarked for special exhibitions, but had no acquisition budget. Morley, who would be named the Director only a few months into the post, believed that the museum ought to stimulate Bay-area artists who were long isolated on the West coast, to “see what the contemporary trends were”, and at the same time “to accustom the public to the modern currents of art”.13Grace Morley, “Oral history interview with Grace Morley,” 6 February to 24 March 1982, unpaginated transcript, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-grace-morley-12774#transcript [last accessed 20 May 2021].

The inaugural program of exhibitions was unavoidably eclectic, including the Art Association’s annual exhibition, French Impressionist painting, Chinese art, and even tapestries. Still, subsequent exhibitions would set the tone for the Museum’s embracement of avant-garde and contemporary art practices, including among others: Cubism and Abstract Art (1936) and Picasso: Forty Years of his Art (1940), organized by MoMA in New York, and smaller exhibitions, such as Henri Matisse in 1937, curated by Morley based on loans from galleries and collectors. These were followed, in the 1940s, by monographic exhibitions of contemporary American art, including Arshile Gorky (1941), Clyfford Still (1943), Jackson Pollock (1945), and Mark Rothko (1946), which led to significant acquisitions for the Museum.14Teresa M. Tauchi, “SFMOMA: 60 Years,” in The Making of a Modern Museum, ed. Kara Kirk (San Francisco: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 1994), 41, 43, 52. In this pursuit, the Museum’s board of Trustees was unsympathetic, made up, in Morley’s words, of “extremely busy and important men in the community but could be said to have no interest in contemporary artor the museum’s way of serving it”.15Grace L. McCann Morley “Art, Artists, Museums, and the San Francisco Museum of Art,” interview by Suzanna B. Riess, 1960, 68, Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, https://digicoll.lib.berkeley.edu/record/217123?ln=en [last accessed 20 May 2021].

Indeed, in the early 1930s, modern art in North America was often associated with women and an interest in interior decoration. As art historian Charlotte Klonk argued, Alfred Barr, Jr. sought to “defeminize” modern art by “masculinizing” MoMA as a profitable business linked to industry and commerce, that is, what the museum’s business-minded trustees could understand and support.16Charlotte Klonk, Spaces of Experience: Art Gallery Interiors from 1800 to 2000 (New Haven/London: Yale University Press, 2009), 151–2.

In the San Francisco Museum of Art, though, it was the Women’s Board that would support Morley in running the institution. Although the board was originally perceived with “the idea of a Lady Beautiful, to receive at receptions and previews”, most of its members represented leadership in the arts or the community and actively engaged with the Museum’s educational program, setting a fund for contemporary local purchases and often subsidizing those museum activities that “wouldn’t, in their busy lives, have attracted the men”.17Grace L. McCann Morley “Art, Artists, Museums, and the San Francisco Museum of Art,” interview by Suzanna B. Riess, 1960, 73, Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, https://digicoll.lib.berkeley.edu/record/217123?ln=en [last accessed 20 May 2021].[Fig. 3]

With a view to educating the Museum’s diverse audiences, Morley and her team would stage a phenomenal 70 to 100 exhibitions per year up until the early 1940s, including, along with larger exhibitions and “who-is-who” displays, also smaller solo shows of local artists. In the same vein, together with clubs and schools, the Museum’s educational program paid particular attention to groups that were not necessarily museum-goers: from kid scouts and worker organizations such as the Bakery Wagon Drivers and the Window Cleaners Union to wounded soldiers through the Arts and Skills program in collaboration with the Red Cross, which also included photography instruction.18For an analysis of these initiatives, see Kara Kirk, “Grace McCann Morley and the Modern Museum,” in San Francisco Museum of Modern Art: 75 Years of Looking Forward, ed. Janet Bishop, Corey Keller, and Sarah Roberts (San Francisco: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 2009), 75. An art course, supported by the Carnegie Corporation, brought together demonstrations of art techniques by artists and lectures on art history and contemporary trends, aiming at “forming a group of leaders in the community, interested in art, somewhat informed, and concerned to give it every possible support”.19Grace Morley, “Oral History Interview with Grace Morley,” 5 February to 24 March 1982, unpaginated transcript, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-grace-morley-12774#transcript [last accessed 20 May 2021]. Alongside an active touring program to regional venues, in 1946, two new programs seeking to enhance public outreach were introduced: the Rental Gallery, which made available to the public artists’ works for rental or sale, and Art in the Cinema, which focused on presenting developments in contemporary art practice. Capitalizing on the popularity of the new medium of television, the Museum also inaugurated, in 1951, the Television series Artin Your Life produced by museum staff, which featured contemporary art and artists to reach audiences in their own homes.20See Teresa M. Tauchi, “SFMOMA: 60 Years,” in The Making of a Modern Museum, ed. Kara Kirk (San Francisco: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 1994), 43.

Morley was clear on the role that photography and film could play in a museum of modern art that fostered public outreach and experiential learning.21The motion picture as a living art form was introduced at the San Francisco Museum of Art in 1937, using MoMA’s motion picture rental services. In the 1930s, there was a strong photography scene developing in the Bay Area. Ansel Adams, Edward Weston, Imogen Cunningham, and Willard Van Dyke were locally based photographers whose shared interest for a clear departure from mainstream Pictorialist practice became the basis for the short-lived group f/64. Their work had already attracted curatorial and collecting interest since the late 1920s. Albert Bender, the San Francisco insurance magnate and art patron, had offered to publish Adams’ first portfolio Parmelian Prints of the High Sierra in 1927 while the Director of the M. H. de Young Memorial Museum, Lloyd Rollings, offered Weston an exhibition in 1931, which was followed by monographic exhibitions of work by Imogen Cunningham, Adams, Van Dyke, and Brett Weston, as well as the f/64 first group exhibition in 1932.22See Sandra S. Phillips, “In the Beginning: Photography at the New San Francisco Museum of Art,” in San Francisco Museum of Modern Art: 75 Years of Looking Forward, ed. Janet Bishop, Corey Keller, and Sarah Roberts (San Francisco: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 2009), 95–101.

Adams was becoming a central photography figure not just in the San Francisco art scene. Through his friendship with Beaumont and Nancy Newhall and the collector David McAlpin, Adams was also involved in the establishment of the Department of Photography at MoMA New York, where he served as Vice-Chairman of the Photography Board. Adams was the curator of the exhibition A Pageant of Photography that was presented at the Golden Gate International Exposition in 1940. This was an exhibition that, brought, in Adams’ words, for the first time “photography in many of its approaches, to the attention of the people in the West.”23Ansel Adams, “Conversations with Ansel Adams: Oral History Transcript/1972–1975,” interview by Ruth Teiser and Catherine Harroun in 1972, 1974, and 1975, Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, https://digicoll.lib.berkeley.edu/record/217383?ln=en [last accessed 20 May 2021). Morley was invited to write the text for motion pictures in the exhibition catalog.

Over twenty photography exhibitions were organized in the first ten years of the Museum’s operation, starting, in 1935, with San Francisco Bay Bridge Photographs by Peter Stackpole, taken with the new miniature camera that very year. [Fig. 4] Looking at the list of exhibitions in the period in question one can see that Morley’s “democratic”approach did not exclude genres, vernacular or amateur practices: from travel photographs, pictorialist practice, and fine art photography on loan from MoMA, best-of exhibitions and monographic shows by Adams and Brett Weston to military and architectural photographs, also including, local and international salons and camera club shows. [Fig.5] Correspondence with Adams reveals that Morley was skeptical about concentrating on art photography, the kind that Adams and Beaumont Newhall, the curator in chief at MoMA’s new Department of Photography (est. 1940), were promoting on the East Coast.

With an art historical background and museum studies at Harvard University, Newhall was keen to establish an art language for photography that would bring to the fore its unique characteristics as an “esthetic” medium. The qualities of “pure” (so-called “straight”) photography—form, detail, clarity, tonality, extended depth of field, and total control over the photographic process—that Adams and his acolytes in the f/64 group supported, were part and parcel of Newhall’s lexicon as well.24For a discussion of Newhall’s thesis, see Alexandra Moschovi, A Gust of Photo-Philia: Photography in the Art Museum (Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2020), 42-46.

Newhall had programmatically stated that the remit of his Department would be “pictures” that were “a personal expression of their makers’ emotions”, and which made use of “the inherent characteristics of the medium of photography”.25Beaumont Newhall, “The Program of the Department,” The Bulletin of the Museum of Modern Art 2,2 (1940–1941): 4. The Department’s opening exhibition 60 photographs: A Survey of Camera Esthetics, in 1940, was devised by Newhall and Adams to offer “clear evidence of an understanding of the qualities, limitations, and possibilities of photography” that defined “camera esthetics”.26The Museum of Modern Art, “The Exhibition: Sixty Photographs,” The Bulletin of the Museum of Modern Art 2,2 (1940–1941): 5. For installation views of the exhibition and the press release, see “Sixty Photographs: A Survey of Camera Aesthetics,” 31 December 1940–12 January 1941, MoMA, https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/2089 [last accessed 20 May 2021). Still, their selection excluded color, commercial, scientific and advertizing work while the self-referentiality of “camera esthetics” and the lack of contextualizing explanation estranged the uninitiated: “What is so hot about rows of lettuce, or mud puddles or tumbledown sheds (…)”, a critic visiting the exhibition wondered.27Mabel Scacheri, “Your Camera,” New York Telegram, 10 January 1941.

Morley was aware of current developments at MoMA, and often hosted MoMA’s touring exhibitions, but did not want to exclude vernacular or popular photography from her museum. In June 1943, she wrote to Adams asking for guidance with regards to the Museum’s photo Forum, which she conceived as a space for the people to share their images with a larger public, beyond the intra-muros competitions and salons of camera clubs.28Grace McCann Morley to Ansel Adams, 23 July 1943, 1943 Artist’s Correspondence, Office of the Director 1935–1956, Administrative Records, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art Archives.

Adams sternly commented that the problem with the appreciation of photography was, by and large, that a great number of people “go into it as an amusement, not as a deep expression”. The Museum had to decide if they were interested in an amusement that could attract public interest or “true expression”for the purposes of which they should “forego a popular response”.29Ansel Adams to Grace McCann Morley, 13 July 1943, 1943 Artist’s Correspondence, Office of the Director 1935–1956, Administrative Records, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art Archives. Adams also proposed a series of strategic actions, ranging from establishing a dedicated Department of Photography, planning a comprehensive survey of photography with an emphasis on contemporary practice and an educational exhibit to allow people to see “photographically”, building a collection of “fine photography” and a photographic library, and marking a clear distinction between “individualistic-creative” practice, “functional” and “amateur-pictorial” photography.30Ansel Adams to Grace McCann Morley, 13 July 1943, 1943 Artist’s Correspondence, Office of the Director 1935–1956, Administrative Records, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art Archives.

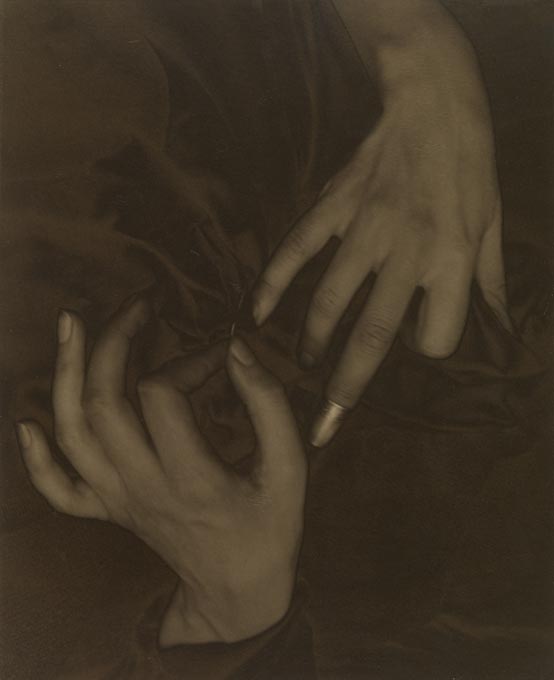

To Adams’ patronizing advice, Morley replied that although she, too, wanted to see the standards of photography raised, amateur photography was a vehicle for “bringing people in contact with some of the basic principles of art in general and yet allowing them a certain amount of freedom of choice where they could exercise their minor talents”.31Grace McCann Morley to Adams, 3 August 1943, 1943 Artist’s Correspondence, Office of the Director 1935–1956, Administrative Records, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art Archives. For Morley, photography was also a folk art and an educational tool that could bring different audiences to the museum. With regards to Adams’ proposal for a department of photography and a collection, Morley explained that despite her willingness, due to limited resources, both in terms of staffing (at the time operating with eight out of twenty staff) and finances, this could only be contemplated after the war. Indeed, with money being very tight at the Museum, photographic acquisitions relied on gifts or copious fundraising as was the case with the Stieglitz collection for which Morley lobbied with Adams and Minor White among others for over six months to raise US$2,500 dollars to purchase the prints from Georgia O’Keefe in 1952.32Corey Keller, “Alfred Stieglitz’s Georgia O’ Keefe-Hands and Thimble,” in San Francisco Museum of Modern Art: 75 Years of Looking Forward, ed. Janet Bishop, Corey Keller, and Sarah Roberts (San Francisco: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 2009), 56. [Fig. 6]

Unfortunately, the director did not see her plans for a photography department materialize. Despite her successes, Morley faced many challenges, financial, ideological, and personal. In 1958, the director resigned unwilling to sustain progressively “unfavorable” conditions, as she stated.33Grace L. McCann Morley “Art, Artists, Museums, and the San Francisco Museum of Art,” interview by Suzanna B. Riess, 1960, 224, Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, https://digicoll.lib.berkeley.edu/record/217123?ln=en [last accessed 20 May 2021]. Scholar Kristy Phillips has claimed that these “unfavorable conditions” were equally fuelled by certain wealthy museum trustees’ unease with Morley’s status as a single woman in a leadership job as much as her unconventional appearance in tailored suits, “abrupt” manners, and debated sexuality.34Kirsty Phillips, “Grace McCann Morley and the National Museum of India,” in No Touching, No Spitting, No Praying: The Museum in South Asia, ed. Saloni Mathur and Kavita Singh (London/New York: 2015), 133.

Yet, prejudices and odds never stopped Morley. After leaving San Francisco in 1958, she became Assistant Director at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York before taking over the directorship of the National Museum in New Delhi for six years. In India she also founded a regional office for the International Council of Museums (ICOM) that she headed for ten years.

Morley’s contribution to the institutionalization of photography in the 1930s has been largely overlooked, not just because her departure for India seemed to erase her valuable museum work from historical memory, but also because her liberal views of modern art and photography went against the grain of the historicization of Modernism advocated at MoMA on the East Coast. Unlike Newhall who, during his brief tenure as photography curator at MoMA, established a niche for art photography that excluded applied photographic practices, photojournalism, and vernacular photography, Morley embraced photography as an egalitarian, inclusive art, as if predicting photography’s novel judgement seat in the new millennium. For Morley, beyond use value, pedigree, and subject matter, photography, like any other art, should be appreciated on its own merits, not simply because “it has an interesting theme and is good documentation”.35Grace McCann Morley to Minor White, 23 May 1952, 1952 Artist’s Correspondence, Office of the Director 1935–1956, Administrative Records, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art Archives.

Alexandra Moschovi is associate professor of photography and digital media in the Faculty of Arts and Creative Industries at the University of Sunderland. A review of her recent book, A Gust of Photo-Philia: Photography in the Art Museum, published by Leuven University Press, can be found on The Classic Platform.