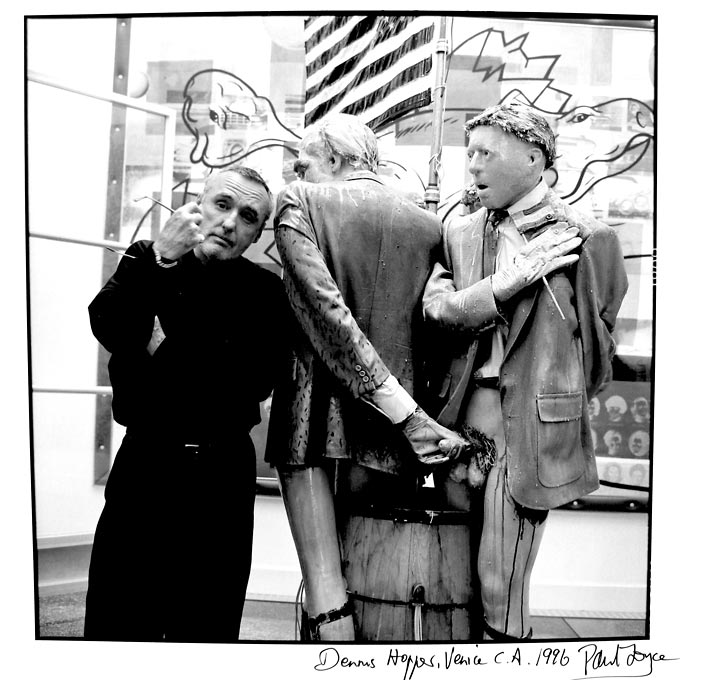

British filmmaker, photographer and painter Paul Joyce first met Dennis Hopper in 1986 while making the documentary Out of the Blue and Into the Black. They became friends and remained so until Hopper’s death in May 2010. This article, first published in The Arbuturian in 2010, is Joyce’s personal tribute to Hopper. He shares numerous anecdotes, as well photographs he took of Hopper in his hometown of Venice, California. It is a poignant portrayal of a pioneering Hollywood rebel with a cause who will be remembered as one of the greatest screen icons of our time.

It was different working in British television back in 1986. They thrust money in your purse and sent you around the world, and even threw in film crews. At that time Jeremy Isaacs (who, as well as setting up Channel 4, acted as godfather to me and my company Lucida Productions) heard me talking about the unique LA based independent production company BBS and how important it was as a trailblazer in the US indie cinema sector (remember that Jeremy had recently incorporated C4 in order to undertake just such a transformation of the UK independent television sector). My business partner at that time, Chris Rodley, fortunately knew one of the key players in the game, Dennis himself, from a previous encounter when he had set up a London screening of The Last Movie. Before we knew it, we were bundled onto a 747 and told to come back with two “riveting” hours of primetime television. What an extraordinary thing that seems now, in an age when the arts documentary has difficulty getting arrested, let alone financed or even (God help us) aired.

It is curious that BBS was little known then, as indeed it still is now, even though its activities had placed a small but significant time-bomb into Hollywood’s very foundations. Bert Schneider, a legendary producer whose father worked for Columbia, set up BBS and would stamp his indelible mark on Hollywood with a handful of great pictures – Five Easy Pieces (1970), The Last Picture Show (1971), The King of Marvin Gardens (1972), etc. But before BBS emerged (the initials standing for Schneider, director Bob Rafelson and artist’s manager Steve Blauner) came a couple of runaway successful pictures that helped finance the whole operation. One was Head (1968), starring pop phenomenon The Monkees and the other, Easy Rider (1969), which announced the arrival of a very special talent indeed, director Dennis Hopper.

In order to tell the complete BBS story, we intended to confront the prime progenitor of this tremendous run of American cinema. The problem was, at the very moment our plane began its descent into LAX, Dennis Hopper was being carted off to a clinic with a suspected overdose, the result of severe alcohol and substance abuse. Oh dear, what to tell Jeremy Isaacs back home? Well maybe best to keep schtum. Get on with something else. Perhaps our man may even recover?

And here Bert Schneider came to the rescue – as he did on a number of occasions in Hopper’s life and career – by visiting Dennis in hospital at his lowest ebb, by gently cajoling and encouraging him to try driving again, going out again, using a camera again. This act of friendship carried Dennis through his worst moments and helped him to emerge, seemingly unscarred, three weeks later into our open, camera extended arms.

During the three weeks or so that we were waiting for Dennis to recover, I shot more film in a short month than I have before or since. Apart from laying down the two hours of the BBS story (Out of the Blue and into the Black), I did a 90-minute film on Monte Hellman (Plunging on Alone) another on Peter Bogdanovich (Pieces of Time) and ultimately a final one on Dennis himself (Some Kind of Genius). So we were by no means just lounging around hotel pools, as some of the early C4 commissions chose to spend their time, and money, without on occasion even completing the film they were charged to deliver!

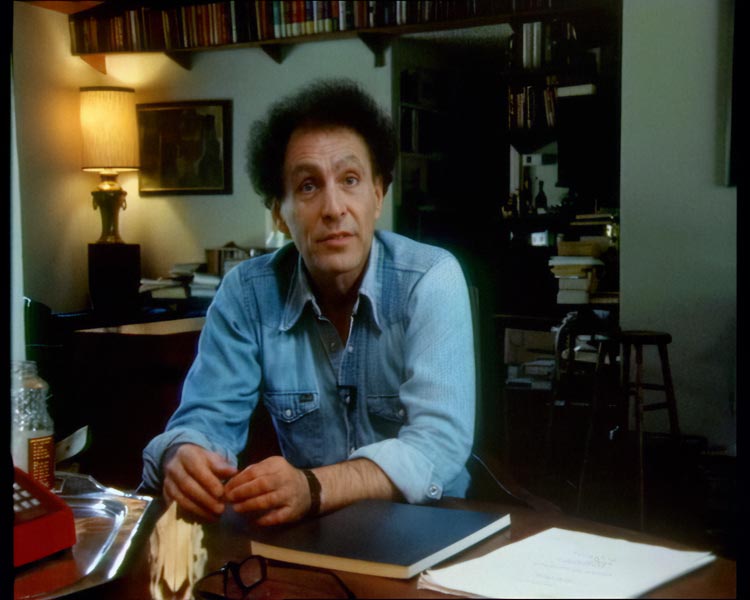

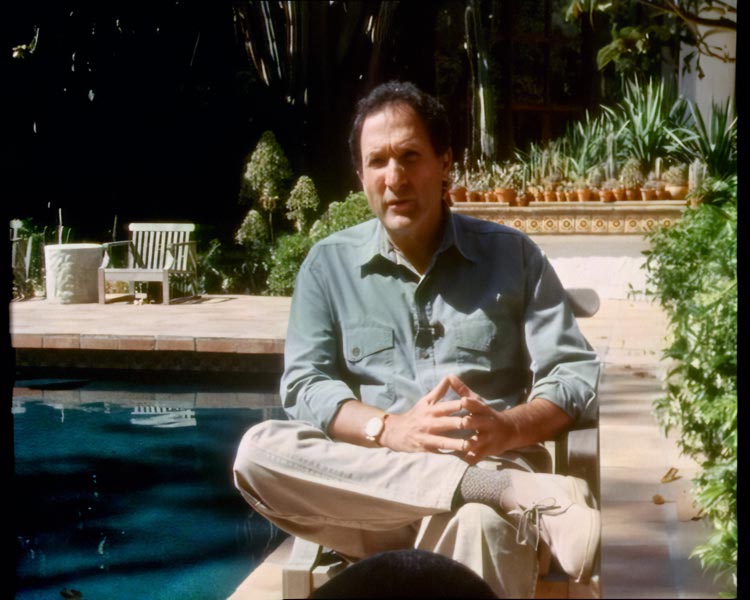

When we finally got the call to say we could now visit, it was with great trepidation that we approached Dennis’ house in Venice, a suburb of LA. But his chosen retreat on Indiana Avenue was not located in the top end of town by any means, but in the decidedly ‘wrong side of the tracks’ area, in what seemed to be a large galvanised shed surrounded by abandoned cars and shopping trolleys. It was here that Dennis would spend over thirty years hunkering down and gradually increasing the perimeter’s fortifications, rather like John Wayne might have done with his garrison in Fort Apache. And I can assure you the natives here were quite as unfriendly as John Ford’s.

Gingerly, Chris Rodley edged forward to the door as we hung around the unit vehicles, nervously puffing on Marlboro Lights (as everyone did then). After fiddling with the entry-phone, which was still faulty on every occasion I visited, which must have been thirty times over as many years, Chris disappeared shortly to be followed by his beckoning finger poked round the door indicating it was “all OK”, a signal agreed in advance. In we piled to find a suntanned and very fit looking Dennis, neatly coiffured and dressed like an enormously wealthy investment banker or hedge fund manager: dark grey silk suit with discreet stripes, matching tie and a dark shirt with tiny white polka dots. Clearly master of the situation and the soul of hospitality, he was “off” everything but cigarettes, which he chain-smoked whilst we were there, using the 100mm-sized white tubes as batons to reinforce points during the filmed interviews (he gave up cigarettes shortly after this, and stayed clean until in the last decade of his life when he developed a penchant for Havana cigars).

But first things first…

Dennis Hopper was born in Dodge City Kansas in 1936 and trained in classic theatre at The Old Globe Theatre in San Diego, before moving to New York to study with Lee Strasberg at The Actor’s Studio. It was at this time that he met James Dean, and they immediately became friends. Dennis not only idolised Dean, he also learnt a huge amount from him, including lessons in acting that would remain within him forever. For example, Dean advised him, when approaching a particular scene, to simply perform an action without contemplating it in advance. “Don’t act drinking from a cup,” Dean said, “just take the drink!” Dennis was convinced that Dean’s ability to perform on-screen action, containing himself when he had to and then exploding into movement, came from his hard work in basic training as a dancer. It gave him a balletic quality that Dennis greatly admired, but was unable fully to emulate. Dean and Dennis worked on two pictures together, Rebel Without a Cause (1955) for Nicholas Ray, and Giant (1956) for George Stevens, the latter of which was merely two weeks away from the end of the shoot when Dean died. From talking with Dennis over the years, it was clear that he would continue to feel the loss of this developing friendship for the rest of his life, and in a sense would never quite recover from this premature bereavement. Dean was the reason Dennis took screen acting so seriously, Dean was why he picked up a stills camera, and Dean it was who also turned him towards the career which would obsess him for the next half century – directing films.

A few minor television roles led to an offer from Hollywood for Dennis to star in a western to be directed by notorious actor-killer Henry Hathaway. Hathaway was regarded by many as the epitome of the cigar-chomping, whip-cracking old-style director who intimidated actors, particularly inexperienced ones, and this was to be Dennis’ ordeal by fire. The film was a western, From Hell to Texas (1958) and hell indeed it proved to be. The scene was simple, a few lines only, and Hathaway gave Dennis explicit directions as to the gestures and line reading. They began at 8am in the morning and by 6pm Hathaway had rejected 85 takes and Dennis was reduced to a tearful jelly. In the meantime, both the head of Universal and Jack Warner himself had called Hopper saying, “Hey, kid, what are you doing, this is Hathaway you are fucking with here!” Halfway through this farrago, Hathaway took Dennis aside and gestured to the corner of the set. “What are those?” he demanded. “Why,” Dennis replied, “they are film cans.” “That’s right, kid” responded Hathaway, “and I own 40 per cent of this studio and we’ve got enough film to shoot here for months if we need to!” Finally, on take 86 Hopper capitulated and completed the scene as Hathaway had demanded nine hours before. As he stumbled away from the set that day, Dennis also left the business (or rather the business left him) for the rest of that decade.

Eight years later – with a rapid fade-out followed by an extremely slow fade-in – Hopper is considering 100 different ways of disposing of Hathaway when he takes a call from the man himself. No announcement or even a “How are you?” just, “Hey kid, do you want to be in my next picture?” Apparently, John Wayne (The Duke) and Hathaway have taken pity on Dennis because he is now married to Margaret Sullivan’s daughter Brooke Hayward, who in turn has produced a daughter of their own, Marin Hopper, and the old stagers want to give Dennis a chance to re-enter the ranks of the Hollywood blessed. According to Dennis, he is offered exactly the same part – the weakling son of a crooked father – with the same lines, motivations, western location, everything. So in front of The Duke, Hal Wallis and a line-up of the studio dignitaries on the set of The Sons of Katie Elder (1965), Dennis takes Hathaway’s instructions and line readings to the letter, and delivers the dialogue as instructed in a single take. Hathaway calls “Cut!” and goes to embrace Dennis with tears in his eyes. “That was great, kid, just great!” Dennis looks up at him and says, “You see Mr Hathaway, I’m a much better actor now.” Hathaway drags the cigar out of his mouth and says, “You’re not better kid, you’re just smarter, you’re just smarter.”

CHATEAU HOLLYWOOD

Although we had tucked ourselves into what was to become Lucida’s LA outpost for over a quarter of a century, “The Magic Motel” in West Hollywood, we spent a good deal of time at the infamous Chateau Marmont. I had known it since 1978 when I stayed there with my actor friend David Warner (in Hollywood to make Time after Time (1979)), at one of the bungalows around the pool; come to think of it I do believe it was the same one that John Belushi expired in, in 1982. It was a place redolent with history. Looking up at the illuminated façade from outside at night, you fully expected to see the ghost of Jim Morrison hanging precariously from the roof as he tried to swing himself through his bedroom window (God knows why) thereby using up, as he later said, ”one of my eight lives”. And was that Howard Hughes, light gleaming for a moment on his binoculars, as he peered at the girls in the pool from his attic apartment? I did actually see a real-life Leonard Cohen relaxing under a huge sunhat in the garden, but although not an everyday occurrence, such a sight was by no means unusual.

During the time of Dennis’ 1986 hospitalisation, our film crew were not merely hanging around the Chateau, we were also busy interviewing the victims and benefactors of Dennis’ notorious approach to creativity. We especially wanted to illuminate the time between Easy Rider and the incorporation of BBS, and one who could help us was granite-jawed top studio boss Ned Tanen, then President of Universal Pictures, who had to deal with Hopper in the aftermath of his huge initial success.

By the time we spoke to him, Ned had been poached to do the same job by Paramount Pictures, so we met him on the famous Paramount lot in an executive bungalow kitted out in Native American and Mexican artefacts. Ned was a no-nonsense guy, but even he was confounded by Hopper’s next project after Easy Rider. The film The Last Movie is about how western “culture” can corrupt a primitive culture almost in a single encounter. It is based on a wonderful premise: when a Hollywood production company shooting in a primitive area (in this case Peru) moves on, the natives continue to make their own “pretend” movie with bamboo cameras and wooden props. The twist is that instead of using blanks for their gun battles, as the film company did, they use real ammunition. The problem for Ned Tanen was that Dennis had been introduced to the films of the nouvelle vague, whose philosophies of film-making were not exactly compatible with Hollywood.

Tanen found himself commuting between Hollywood and Peru during the shoot, and then on to Taos New Mexico for the editing; both stages were fraught with danger and despair. “People in the crew flew down there, went into the jungles, and simply never came back!” Tanen told us. A mad cocktail of drink, drugs and willing native women overwhelmed many, with Dennis acting as a stoned ringmaster pulling all the strings, but mostly tangling them into a giant Gordian knot. Tanen remembers a visit when he literally encountered a genuine Taos orgy. Not a man to be shocked easily, Ned was aghast, “There were thrusting buttocks and tits everywhere, it was like a cut scene from Caligula but for real!” In a hopeless attempt to conduct the business he had come for, he managed to locate Dennis’ writhing body and lightly tapped him on the shoulder, ”So sorry to interrupt, but may I have a quick word with you about how the edit is coming on?”

As had happened with Easy Rider, the first edit – a four-hour cut which Dennis refused to trim down – nearly derailed the whole project. Ned’s frequent, if mainly abortive visits to Taos were punctuated by trips to the fleapit cinema that Dennis had set up for the locals. But attempts to introduce films like Jean-Luc Godard’s Les Carabiniers (1963) to them only resulted in a multi-coloured decoration of local fruit and vegetables being hurled at the screen.

When The Last Movie was finally given a strictly limited US release, this near-impenetrable stream-of-consciousness piece of avant-garde cinema left much of the small audience who bothered to see it confused. This seeming farrago effectively buried Dennis’ directorial career for the rest of his life. But here we are getting ahead of ourselves again, so let us return to the mid-1960s, when youthful enthusiasm and simple pleasures first drove the likes of Hopper, Peter Fonda, Henry Jaglom and Peter Bogdanovitch towards the cinema, and all the promises it seemed to hold for them.

BREAKING IN

At that time, Roger Corman – the king of low-budget exploitation movies – had established a market for biker flicks with The Wild Angels (1966) and Devil’s Angels (1967) and hoped to produce Easy Rider with the backing of cigar-chomping lawyer Sam Arkoff. One day Dennis took a call from friend Peter Fonda who was at a film festival in Canada (they had previously agreed never to do another biking picture fearing they would end up branded as latter-day Roy Rogers and Gabby Hayes). Fonda said he was in a meeting with Arkoff and he had pitched him a story “It’s about a couple of dirt bikers who make money in a drug deal in Mexico, buy two new gleaming bikes, head to New Orleans and get stoned, then get shot by a couple of duck hunters. He said you could direct and I can star! What do you think Dennis?” Dennis replied, “Are you sure Arkoff said he has the money?” “Oh yes,” comes back Fonda “he said he’d give us the money alright”. “Well” retorted Dennis “I think it’s a great story!”

Shortly after at a meeting with Fonda, Corman and Dennis, Arkoff became concerned by the explicit language Dennis was using, and demanded a clause in the contract stating that Dennis could be replaced as director if he fell behind schedule. Hopper’s explosive “Fuck you!” could be heard all over Burbank. Shortly after this abortive meeting, Jack Nicholson moved the whole project to Columbia Pictures. In return for packaging and promoting the project, he took the role of George Hanson, which turned him into a star overnight – a part the unlucky Bruce Dern had previously been earmarked to play.

At this stage of his career Dennis was basically uncontrollable. He made enemies left, right and centre and cared not a jot about it. For instance, he found himself sitting next to George Cukor, director of The Philadelphia Story (1940) and A Star is Born (1954), at a Hollywood dinner. In horror, fellow guest Peter Bogdanovitch heard him say to Cukor, “You’re old Hollywood and we are going to bury you!”

The way that Easy Rider was made and finally completed is a tribute to producer Bert Schneider’s ability to hold together a potentially disintegrating project. Drink and drugs fuelled the production with a great deal of testosterone added to the mix. The shoot began with an infamous trip to the Mardi Gras in New Orleans, with Dennis, by all accounts, behaving like Orson Welles on speed – the unit returned with about 20 hours of incomprehensible 16mm footage. Again, it was Bert who had to drag the two antagonists, Dennis and Peter Fonda (who played the lead, Captain America) apart, thereby preventing mutual emasculation.

Weeks of production activity on the road covered the full gamut of fist fights, orgies, drug binges, drink and rock and roll! After the New Orleans Mardi Gras, Fonda and Dennis’ brother-in-law, Mike Hayward, returned to LA with a stack of on-set tape recordings of Hopper ranting, determined to have him fired from the picture. On one of these tapes, he was heard demanding to know why a particular lighting rig was not in evidence on set. ”Red, blue and green lights making a white light goddamn it!” Schneider conceded that Dennis sounded “a little agitated”, then added, “but if he had asked for a certain red-blue light in advance, and it was not there, then surely he had cause to be upset, didn’t he?” Such a sympathetic view, in the guise of an unanswerable question, was why Schneider was widely regarded as “The Last Tycoon” of his generation.

According to Henry Jaglom, a fellow veteran of the independent film sector, Easy Rider was shown in its five hour and twenty-minute version to an eminent French film critic who exclaimed, “It’s a masterpiece, don’t cut a single frame!”, which Dennis adopted as his own mantra. Enter Schneider, from camera left, to the rescue once more, setting Jaglom at work at one end of the cut, with Jack Nicholson editing at the other end until they met somewhere in the middle. Dennis always maintained that he was personally responsible for the edit, but my pretty strong guess is that Nicholson and Jaglom helped him a lot, and he ultimately approved their work. Dennis also said, well after the event, that he had intended to win the top award at Cannes, but the fact remains that the Palme d’Or going to Easy Rider was a great surprise, and it heralded a new era of bold, uncompromising truly independent cinema.

Steve Blauner then took up the story for our programme; he was helping with the advertising and distribution of the film. Bert Schneider’s father was still a senior executive at Columbia Pictures, so he was able to get the film opened at the Beekman Theatre on East Side, New York City rather than at the drive-in market for which it was originally destined. Then something very strange happened, according to Blauner, “That grapevine thing which, if anyone could predict, would make us kings of show business – word just got around before the opening and there were queues around the block, they were sitting in the aisles, hanging from the rafters, it was pandemonium.” Before long the cinema manager had to unscrew the toilet doors to stop the pre-screening pot smoking.

The massive success of Easy Rider, followed by the equally gargantuan failure of The Last Movie, established a pattern, one that would weave its way, like a poisonous serpent, through Dennis’ subsequent career. After Easy Rider Dennis could have worked with anyone in the world – his acting hero Marlon Brando, for instance – but instead he chose to fire Ben Johnson from the male lead in The Last Movie (an Academy Award winning actor who had once been part of John Ford’s stock company) and put himself in the role. Then he buried himself in the Peruvian jungle for eighteen months.

Even in the context of the drug-fuelled culture of the late 1960s, his behaviour does seem perverse. Rather than being hailed as an artistic statement in the guise of an unconventional western, the ravaged film that finally emerged as The Last Movie was viewed as a vomitus assault on key Hollywood shibboleths. Dennis thereby rendered himself unemployable as a director to any major studio for the rest of his life.

MID-CAREER FRUSTRATIONS

It would be a full decade after shooting The Last Movie before Dennis had an opportunity to get behind a camera again. Made independently on a small budget, Out of the Blue (1980) is a punk-inspired, relentless and hopelessly bleak examination of a dysfunctional family whose father, played by Dennis, wipes out a bus full of school children while driving drunk. The film’s descent of family life into alcoholism and sexual abuse is about as bleak an account of middle America as one could imagine. It’s a brilliant film, but one of such mind-numbing nihilism that paracetamol makes a more suitable foyer-seller at its screenings than popcorn. However, Dennis’ power as an actor and authority as a director was widely acknowledged and the film helped reinforce his reputation as a vastly underrated directorial talent, particularly amongst the European film critics.

Eight years would unwind before Dennis was again able to direct. Colors (1988) was made for Orion, then a major Hollywood player. He had actors Robert Duvall and Sean Penn at his disposal, and a story of drug-dealing and corrupt police, which he transposed from its original setting of Chicago to his very own doorstep, the downtown ghettos of LA. Although this film had some success commercially and even better critical acclaim, it demonstrated Dennis’ attraction to subjects many in the business would describe as “murky”. In this regard he was his own worst enemy. He was unable or unwilling to compromise. Between 1988 and 2000 there would only be three more director credits for him and all were low-budget, low-life thrillers: Catchfire (1990) – re-edited so damagingly Dennis had it credited the infamous pseudonym “Alan Smithee” – The Hot Spot (1990) and Chasers (1994). The meagreness of this body of work was a matter of great regret to Dennis. In a sense, his mischievous persona, used to such advantage by others in the films he made as an actor, sapped his time and energy. He needed a Bert Schneider there to advise and guide him, but when Bert retired from the business as he always said he would at the age of 50, after completing Terence Mallick’s Days of Heaven in 1978, he lost that elder brother figure he so desperately needed to continue with truly creative work.

The acting role with which, of course, he will always be most identified is Frank Booth, the psychotic gangster in David Lynch’s Blue Velvet (1986). Famously, he pestered Lynch for the role repeatedly saying, “There is no problem for me in playing him, because I am Frank Booth!” Having already carved a niche for himself (in acting terms) as a serial abuser, pornographer, drug user and child maltreater, given to outbursts of contumely at any turn, Dennis delivered his star turn for Lynch. Who can forget his explosive, “Baby wants to fuck, baby wants to fuck Blue Velvet!” But even in this riveting performance as one of the screen’s most unlikeable heavies, Dennis found terrible humour, blacker than the night, in the worst of situations. It was this quality that other filmmakers turned to Dennis to supply, for instance in Speed (1994) and Waterworld (1995). In each case Dennis’ arrival served to boost a story when it was flagging, thereby dividing the audiences’ affections between himself and either the wooden Keanu Reeves, or the preoccupied Kevin Costner. In these films Dennis delivered the best performance on view.

His other memorable appearances included the crazed photojournalist in Francis Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (1979); an alcoholic father, again for Francis in Rumble Fish (1983); another alcoholic, this time a basketball star well past his sell-by date in Hoosiers (1986) – for which he received an Academy Award nomination – and a memorable scene-stealer opposite Christopher Walken in Tony Scott’s True Romance (1993). His screen performances totalled over 200, against just eight shots as a director. One wonders if his was dissipated in this constant scrambling up a greasy financial pole erected in the cause of alimony and art purchases.

In the midst of continuing professional crises regarding his directing ambitions, his private life seemed to be weaving an almost parallel course. In 1961 he married Brooke Hayward, the aforementioned daughter of Margaret Sullivan and the infamous Hollywood agent Leland Hayward, a union which lasted eight years. During this time, he began to collect art, almost exclusively American contemporary. He was one of the first people to purchase a Campbell’s soup can by Andy Warhol, for the princely sum of $75. Against a total outlay of just $28,000 he amassed works by Jasper Johns, Roy Lichtenstein and further pieces by Warhol, whom Dennis came to know personally. As part of his divorce settlement with Hayward, he was forced to give up his collection, which she sold for three-quarters of a million dollars (equivalent to over $50 million today). Dennis had to begin collecting again from scratch. He lost his second collection to another former wife, and now his third and final one is the subject of bitter dispute amongst family members even as I write.

At the height of his alcohol and drug abuses, Dennis married Michelle Phillips of The Mamas and Papas, a union which lasted exactly one week (he is reputed to have said “The first six days were great”). She accused him of “unreasonable sexual demands”. Then came a string of dancers, singers, and singer-dancers ending with Victoria Duffy, who was allegedly recently spotted (while Dennis was in hospital receiving chemotherapy) slipping out of the family house with various pieces of contemporary art. Dennis’ attempt to place a restraining order on her preventing her from coming within ten feet of him was apparently ongoing at the time of his death. Sadly, his final appearances looking like a frail King Lear was probably a role he was actually close to playing in his own disrupted household.

The work Dennis achieved as a photographer and artist has, in my view, been disgracefully overlooked, especially in Britain. However, in a typically perverse Hopper-type finale, The Hermitage in St. Petersberg gave him a one-man show in 2008. Some of the work there had been on show in LA. Dean Tavoularis (Oscar-winning Production Designer on most of Francis Coppola’s major pictures) and I made a point of dropping by the Ace Gallery on Wilshire Boulevard on a typical day, with only a few spectators present. The most shocking pieces were the enormous monochrome canvasses, some as large as 10’ x 20’, literally eating up vast walls. Knowing Dennis’s photographic work quite well, we realised that they were painted representations from 35mm frames, enlarged vastly and painted on canvas.

Dean and I looked at each other in disbelief. The scant catalogue and information on the walls seemed to indicate that Dennis had painted them himself. Dean exclaimed, “Dennis would never have had the time or patience to paint all these!” Anyone who knew him well would have known this immediately. So how had the work been achieved? By nosing around the gallery and putting two and two together, it became clear that Dennis had employed other artists to work under his guidance. And who were these artists? Why, those painters of Hollywood signs, like the good old Marlboro Man who used to nestle alongside the Chateau Marmont on Sunset in the 1970s and 80s. Long since made redundant by laser and computer technology, these skilled craftsmen were employed because of their ability to project an image onto an enormous canvas whilst keeping perspective and proportions under control.

What a great idea, we thought, but rather than trying to hide the work’s gestation, why didn’t Dennis use it as a way to make a virtue out of the concept, and to integrate these pieces, basically of poster art, within the tradition he was celebrating? By so doing, he would surely have appealed to a wider public, and why he didn’t explain the concept and execution of this unique new work more explicitly remains a mystery for Dean and myself to this day. So we left, shrugging our shoulders and muttering, “Well that’s Dennis for you, I guess.”

Dennis’ involvement in the art world included strong friendships with David Hockney and Andy Warhol, amongst others, and occasional bizarre events such as the incident in a field in Houston, Texas in 1983. Dennis had been to an opening of Out of The Blue and had announced that he wanted to blow himself up. As he started to wave sticks of dynamite around – I can only assume he meant it to be an “art happening” – city officials bundled him into a car and drove him to a field well outside the city’s limits and its fire regulations. Here, with the help of a stunt co-ordinator and various assistants, Dennis entered a flimsy-looking cardboard structure covered in foil to sit himself on a “Russian Dynamite Death Chair” placed over six sticks of dynamite. There was an agonising pause while he failed to ignite three matches. Then a tremendous explosion occurred, followed by plumes of white smoke, through which Dennis emerged unscathed apart from damage to his eardrums. “Wow, man.” He was heard to mutter, “That’s worse than being hit by Mohammad Ali!” His theory was – and who can now dispute it – that the force of the explosion would be outwards, away from him, and the flimsy plywood structure would insure an even dissolution of the shock waves. Well, I guess he proved his point but he couldn’t hear properly for three months, and as far as I know, the event was never included in his canon of art works (although it can be seen in grainy 8mm on YouTube).

This event occurred not long after reports circulated of Dennis being found wandering in a Mexican jungle, on location for a German film called Euer Weg Führt durch die Hölle — released as Jungle Fever – stark naked, and apparently trying to raise an army for the Third World War. He was detained by local police, declaring himself to be a “prisoner of war” and giving no personal details beyond his social security number. A period of detoxification followed.

VISITING DENNIS

In the mid-nineties I was collaborating on a book with David Hockney (Hockney on Art, Little, Brown, 2000) and we drove from David’s studio just off Mullholland Drive, down to the coast to Venice for dinner with Dennis, accompanied by Hockney’s two Dachshunds propped up in the back seat. In the meantime, that corrugated fortress of a house, designed now with even more jagged extensions by Frank Gehry, was once more packed full of contemporary art, much of it vast in scale. As the living quarters resembled an aircraft hangar with steel girders and tubular walkways running all around us, this new-ish collection fitted the décor like a glove. There were works by David Sale, Julian Schnabel, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring, and an installation by Jenny Holzer which consisted of a running statement in racing neon lights, like illuminated newsflashes in Times Square, reading, “You are so complex, you don’t respond to danger”, or something along these lines. Dinner was great; various personal assistants drifted around and about us, and I really can’t remember which if any current wife was in evidence. Come to think of it they weren’t usually at dinner, which demanded more mental than physical agility of Dennis and his guests. We had a wide-ranging conversation, mainly on art-related subjects, with a few scurrilous stories (decidedly not for publication) about friends and especially rivals. Dennis and David loved gossip, so we had lots of that.

During the meal I noticed what seemed like a portrait of Dennis hanging inconspicuously on the kitchen wall, half hidden by a cupboard. It appeared to be comprised of shattered shards of porcelain. I asked Dennis what it was and who had done it? “Julian Schnabel,” came his reply, “He made it out of the broken crockery on the kitchen floor which my wife threw at me the other day!”

During dinner we had left David’s dogs downstairs in Dennis’ pride and joy, a newly equipped screening room. On the floor between audience seating and screen was an enormous carpet, consisting of a heavily piled, one-piece, dead-white expanse of alpacka. Perhaps you have by now guessed that during dinner one of the dear little creatures had delivered an enormous dump right in the middle of this priceless virgin white field. As we descended to take our leave, David was suitably horrified, gazing around wildly for some kind of solution: of course there was none, for this was an irreparably stained, once expensive but now decidedly ex-carpet. Dennis, without blinking, continued to show us to the door without even acknowledging the disaster, a gracious and immaculate host till the end. We stumbled out, and as David shooed the yelping offenders into the back of the car, turned to me and said mournfully, “Oh dear, do you think this marks the demise of my social life in Hollywood?”

FRIENDSHIP

If Dennis liked you, you were a friend for life. Fortunately, he seemed to like me, as well as my work. For 20 years of us knowing each other, however, he was unaware that I was a painter as well as a photographer and filmmaker (three pillars of our lives which we had in common). During my two or three trips to LA every year, I had been working on paintings of vernacular architecture: diners, motels, “Randy’s Donuts” and the like. Three years ago, I called Dennis and asked if he would like to see them and within an hour he had driven from Venice to my studio in North Hollywood in his Jaguar XJ, Havana cigar in hand. He came in and looked at the paintings for 20 minutes without saying a word. Finally, he said, “You never told me you were a painter”. I wasn’t sure how to reply to this, (“Well you never asked?”) but he hurried on, “They’re great, you should have a show, would you like to have a show here?” Within 48 hours he had introduced me to a top Santa Monica Gallery (Track 16 at Bergamot Station), a show was arranged and he had agreed to personally curate it. That’s the kind of friend Dennis was.

So how will history judge this outrider of the avant-garde, our gritty long-haired symbol of simpler times, roaring down highways and lonely deserts, both real and imagined? I would guess that he’ll take his rightful place in the pantheon of late 20th century American auteurs. Floating on the water of memory, long after his dust has settled, will remain a handful of great acting performances, some wonderful films as a director, three or four incredible art collections dissembled by disputing legatees, many loyal and devoted friends, the respect of his luckier colleagues and an unmatched body of work as a photographer.

My first reaction, after the initial shock of hearing of his death was to feel the irony that it was the old Hollywood he notoriously wanted to bury who ended up burying him. But Dennis, who came to love Hollywood old and new, had the last laugh. He is no longer with those vacillating Beverly Hillsians, for he took his bones to Taos, New Mexico. Spiritual (and physical) home to DH Lawrence, Ansel Adams, and Georgia O’Keefe, what better place is there for an artist to lay himself down? Rest easy, dear rider, for those who love you will surely be visiting again with you one day.

Paul Joyce is a filmmaker, photographer, artist and writer. He is the great-grand-nephew of James Joyce. Dennis Hopper appeared in a total of seven Lucida Productions (the production house set up by Paul Joyce) to the point that he was thought of as the company mascot:

Some Kind of Genius (1986)

Out of The Blue and into the Black (two parts) (1986)

Motion and Emotion: the Films of Wim Wenders (1989)

Pilgrim: The Life and Work of Kris Kristofferson (1992)

Dark and Deadly: Hollywood and Film Noir (1994)

Marlon Brando: Wild One (1996)

Mantrap: Sam Peckinpah and ‘Straw Dogs’ (2003)