The French dealer Barnabé Moinard started his dealership in 2022 and has quickly become a familiar face on the classic photography scene.

I started out by asking him about early interest in photography and the arts.

– As far photography is concerned, it was at the beginning of secondary school. We were tasked with writing an exposé on death and vanity in art and to find an image to illustrate it. In a catalogue from the Fondation Cartier pour l’Art Contemporain, I found a self-portrait by Robert Mapplethorpe against a black background, holding a walking stick with a skull on the handle. I acquired other catalogues at the time, Amours, Déserts, Comme un oiseau, By night, followed by Art du nu and the catalogue for the exhibition of the Roger Thérond collection, Une Passion française. I didn’t know it at the time, but all the photography I would come to love was there, within easy reach on the living room shelf. My father, an architect who also paints, took us to exhibitions and brought home the catalogues.

At the time, he was the designer of most of the exhibitions at the Fondation Cartier pour l’Art Contemporain so we often went to the openings. I remember one instance. It was spring, I was 7 years old and I was playing in the museum’s garden on Boulevard Raspail. I didn’t understand it, but I saw and associated art with a real place, with unusual forms and later with these catalogues. I therefore came into contact with the arts at an early age, as a backdrop, provided by my parents, who wanted us to build our own imaginary inner world. My mother also made sure that my sisters and I were open-minded and independent, and she led us towards music and literature.

Did you study photography? If so, where?

– It was after a degree in art history that I turned to photography. During the research for my master’s degree at the Sorbonne I focused on American photography, in particular on Louis Faurer, who hadn’t been shown much in France. In the two years of my master’s degree, my career path took shape. I met artists, gallery owners and curators like Christine Barthe whom I met during my internship at the Musée du Quai Branly. Then my research supervisor suggested Arles. I passed the entrance exam and joined the ENSP (Ecole Nationale Supérieure de la Photographie) in 2013. Unlike other schools with a purely technical profile, the ENSP, in addition to developing the practical dimensions, from the shoot to the laboratory, gives space to history and research, as well as the development of an artistic approach. Those years of training have given me a mastery of the history, theory and practice of photography. This knowledge doesn’t solve everything, but it does help when I’m faced with a photograph, to contextualise it, appreciate it, grasp and understand it.

Were you a collector before you became a dealer?

– I’ve never collected because it doesn’t fit in with my way of being. Collecting implies a material relationship with things that is too far removed from my goal which is to discover and surprise. The desire is in the search, not really in the possession. I love searching and I love creating sets of images. Everything is for sale! Above all, I like movement, when things are in constant motion.

When did you become a dealer?

– Officially, Barnabé Moinard Photographies was created in 2022. But let me take a step back in time. I was 16 and at school I had to do an internship and the art market appealed to me. I chose a pre-Columbian art expert whom we were close to. He took me to Drouot and we set up sales. I followed him around and we went to the auction house Binoche & Giquello. One morning he sent me off on my own to pack a collection of Guerrero statuettes in a large flat. I was immediately fascinated by this new profession of expert and dealer. Later, in 2017, something clicked when I rang dealer Serge Plantureux’s doorbell. In a way, everything became clear at that moment. I learnt a lot – and even relearnt d a lot – at his side. He gave me the impetus I needed. Standing in front of the boxes of photographs and the racks full of prints in passepartout, I rediscovered the happiness I had felt one June morning surrounded by my Guerreros. Looking back, setting up as a dealer was the logical culmination to my itinerary.

Are you a full-time dealer?

– I chose to be a full-time dealer so that I would be fully invested and not be tempted to rely on a safety net. It’s not always easy, but it’s exciting! There’s so much to do and imagine, and you have to be available: flea markets at 7am, 11am at Drouot, various client meetings and so on. It’s a risk worth taking, and we’ll see what the future holds. As they say, you have to be in the game to play the game.

What kind of material do you focus on?

– Broadly speaking, I start in the 19th century and go up to the 1960s/1970s.

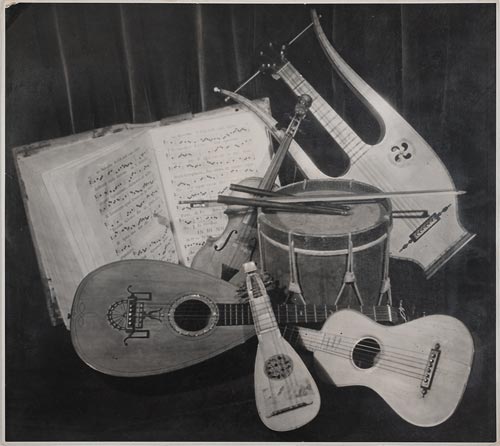

Architecture, sculpture and travel on albumen paper are my favourite areas in the 19th century. In film, I’m interested in all those photographs that had no artistic pretence when they were taken: archives, documentation, scientific or press images. I track down names that are under the radar or strong individual images. By following these two tracks I try to reconstitute coherent and relevant sets.

Some of what I offer are images that have no history or signature, but are unique and need to be shown and contextualised, “activated”, as one does with an abstract piece of art. Offering yet another posthumous ‘signature’ print doesn’t inspire me at all. My prices range from €50 to €5,000, but most of them average between €200 and €2,000.

I have met you at table-top fairs and you are active online as well. Can you tell me a little about how you operate?

– When I set up the company, I wanted a motto to define it. It’s a bit old-fashioned, but it’s elegant and very effective! “Ignoti nulla cupido” is an aphorism from Ovid’s The Art of Love which could be translated as “You don’t desire what you don’t know”. It’s this idea that sets the course for operations, so to speak.

For me, the challenge is to work with my generation and develop a new clientele. Admittedly, the market is not what it once was but listing the problems won’t make any headway. Tastes have changed, as have the way people buy and collect. Nonetheless, people are interested in real, vintage paper prints that tell a story, that are on a wall and not on a screen. It’s a bit like the return of the LP and Kodak film. We need to come up with new itineraries and promote them.

I operate with this conviction in mind. I try to be active, to reach out to people on Instagram for example. I also regularly send out a newsletter featuring a particular photograph or a selection of recent acquisitions. The protocol is always the same: a technical description of the print and visual description of the image, a presentation of the photographer or the period, followed by a broader reflection, and a price.

I use the networks like spontaneous, light-hearted postcards: easy to write, well-documented, pleasant and quick to read.

As for fairs, I try to do them regularly. They’re important to me, because it’s through them that I can make my mark on the scene, and above all, meet other dealers. Taking part forces you to raise your game and refine your positioning. Show me what you have on your table and I’ll tell you who you are!

At the moment, having a gallery is not the priority. When someone contacts me, we have a chat and then agree on a meeting, either in an office or a café. I bring one or two boxes, a bit like Marcel Duchamp with his Boite-en-Valise, and we look at the images. I bring the excellence of a gallery to a place where the client feels at ease.

Can you discuss some works you have sold?

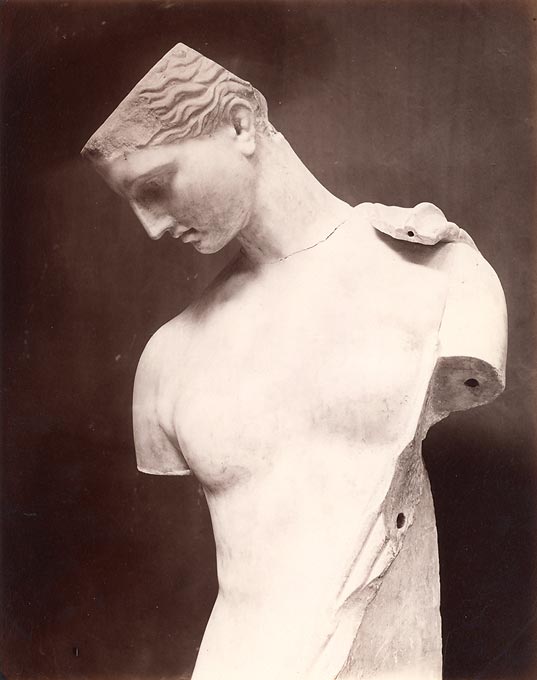

– Two superb images that illustrate my penchant for sculpture and Italy. The Psyche of Capua, an albumen print, in perfect condition, which is probably the most beautiful sculpture in history. She is both an antique model and a damsel from Avignon.

In the same vein, the Tomb of Giuliano de Medici by Michelangelo, again a perfect print of a very elegant and powerful image.

A large raw, authentic print showing the Ile de la Cité seen from the Left Bank. An unusual view of Notre-Dame around 1865, hidden by the Hôtel-Dieu building, which was demolished in 1867. Advances in medicine, Second Empire works, renovation of the cathedral: this photograph is an important social and urban planning archive. The stalls on the left and the two figures in the sunlight in the foreground complete the composition of this scene, which evokes Baudelaire and his The Swan, “Le Vieux Paris n’est plus…”

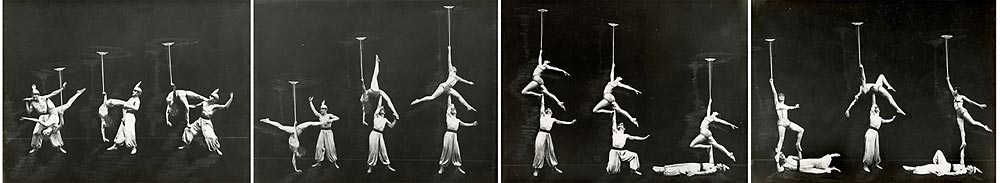

Next is a leporello sequence of the two acrobats Lys and Jol in the 1930s. It’s a commercial brochure promoting their show, which is presented as “a fairytale of Hindu strength and precision”. The work is extremely delicate, reminiscent of E-J Marey’s gymnastic exercises.

Roger Parry’s very melancholic composition is quite surprising when you consider his daring experiments. But the magic of the darkroom is palpable: you can recognise the double-exposure image in Nature morte au tourne-disque (c.1930) in the Centre Pompidou.

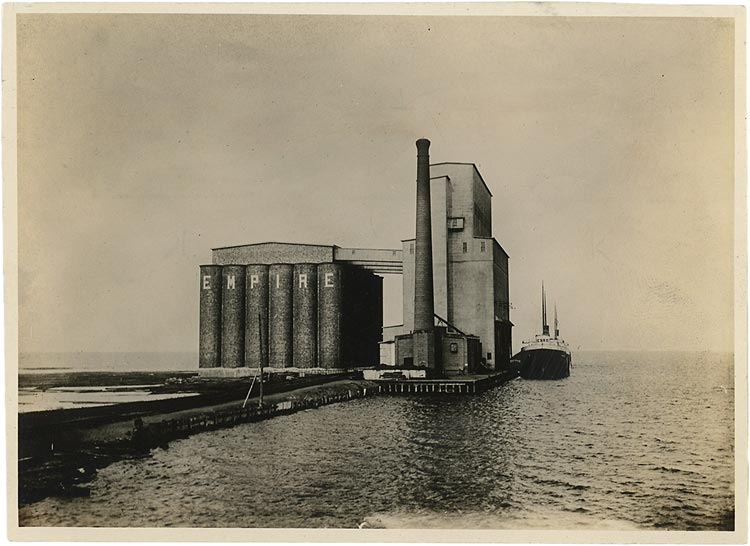

Empire is what I call an image to be activated. It has something of the conceptual photography of the 1970s: all the more modest in form, almost poor, with no artistic pretensions, but it is powerful, poetic and rich in meaning. With this word in capital letters, this photograph finds a place between a letter written on a shop window, photographed by Lee Friedlander, and a phrase heard on the radio, painted by Ed Ruscha.

Let’s move on to some images you have in stock now.

– Recently, I acquired an albumen print that intrigued me. A large group of people in a garden. The tones are beautiful, there’s a density and there’s something I can’t explain that makes this print fascinating. Right now, I’m trying to work out where this garden might be, who these people are and why they’ve gathered together.

There’s also an image of a different kind of group by Alphonse Bernoud: Capuchin monks in Florence, marching in procession, fully covered in eery black head coverings and robes, for the funeral of a brother.

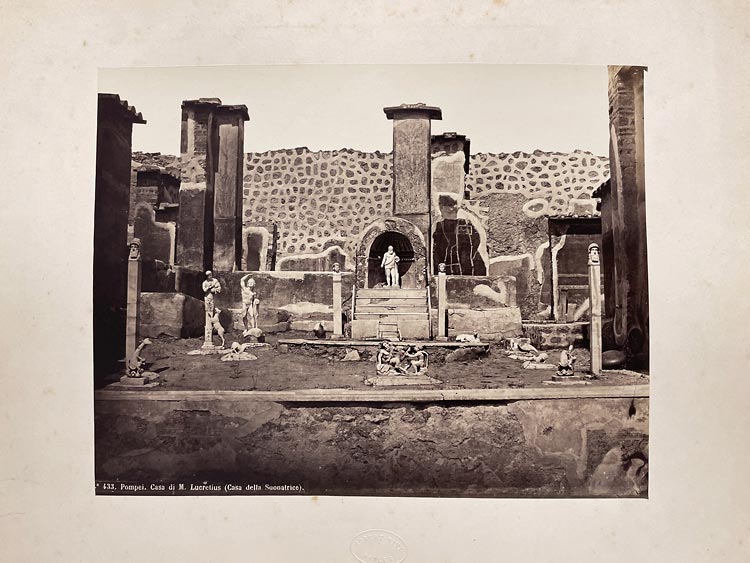

I continue to be interested in sculpture, which is an important part of my research. A classic but very beautiful version of the House of Lucretius in Pompeii has just been added to the stock.

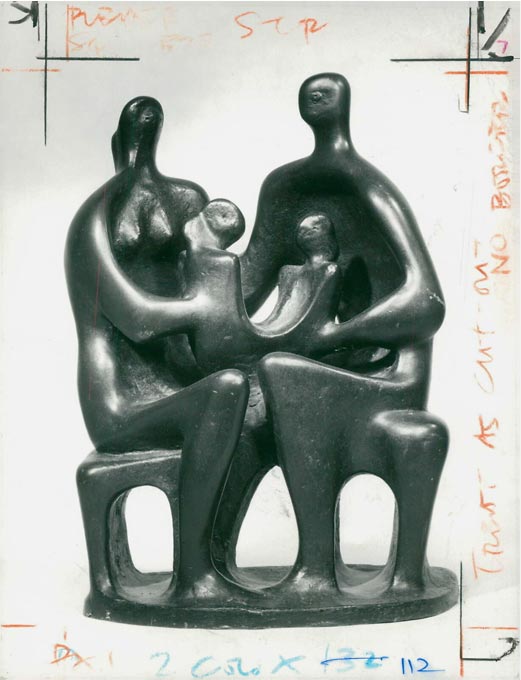

I have also acquired a press print of a family group by Henry Moore.

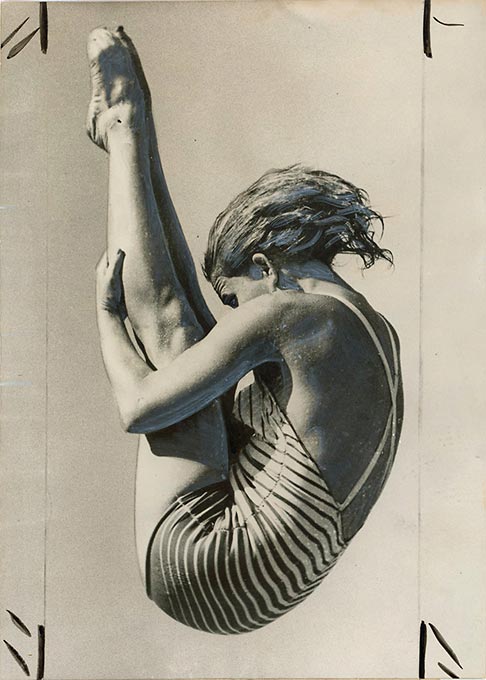

Finally, and because we’re getting ready to host the Olympic Games in Paris this summer, I’ll finish with this absolutely crystal-clear dive that needs no explanation.

My wife always says that a healthy meal is one in which there are at least five colours. I make sure that my stock is like that meal: a coherent but eclectic whole, made from natural, fresh and mouth-watering products!

All images courtesy of Barnabé Moinard.