When and why did you first get interested in the history of Polar exploration and writing about it?

– In 1989, after moving to Cheltenham in Gloucestershire, I regularly passed a statue of Edward Wilson, who died with Captain Scott and three others on their return journey from the South Pole in 1912. When I saw Wilson’s wonderful Antarctic paintings and drawings in Cheltenham’s art gallery and museum, I was impressed – particularly so, given Wilson also served as expedition doctor and chief scientist! I became interested in writing about polar history in 2010 after completing a creative writing course project which required me to read an old family copy of a 1930s biography of Henry Bowers, the youngest member of Scott’s South Pole party. As the expedition centenary approached, I noticed that Gloucestershire-based publishers The History Press had published a new biography of Wilson, so approached them with a proposal for a companion volume on Bowers. By early 2011 I was on my way to Antarctica, where I visited Scott’s and Shackleton’s expedition huts and saw the same wonderful scenery that Wilson painted and Herbert Ponting photographed.

Your first two polar-related biographies were Birdie Bowers: Captain Scott’s Marvel and From Ice Floes to Battlefields – what inspired you to write about Scott’s photographer, Herbert Ponting?

– I already knew Ponting’s Antarctic images from my first two books, but during the Scott expedition centenary period enjoyed seeing enlarged photographs in exhibitions and recently remastered versions of his Antarctic films. When helping with research on re-discovered South Pole journey photographs taken by Bowers, I realised that H.J.P. Arnold, author of a 1969 Ponting biography, could not have known the whole story. As 2020 was the 150th anniversary of Ponting’s birth, The History Press commissioned Herbert Ponting: Scott’s Antarctic Photographer and Pioneer Filmmaker – although the Covid outbreak meant it could not be published until 2021!

Ponting had an extraordinary life and career. Can you describe his early life and how he became a professional photographer?

– Ponting was born in in 1870 in Wiltshire, his parents’ home county, but his family moved several times in pursuit of his father’s banking career. After a disjointed education Ponting joined a bank in Liverpool but seemed more interested in climbing in the Lake District and in photography (an interest fuelled by seeing stereoviews as a child) than in filling in ledgers. While in Liverpool Ponting bought cameras including a Fallowfield ‘detective’ and an early Kodak compact model which produced round photographs. He also joined the Liverpool Amateur Photography Association (successor to a camera club co-founded by Francis Frith), which mounted international photographic exhibitions where he could see work by leading British and international photographers (including a young Alfred Stieglitz) and enjoy stereoview and lantern-slide shows and Eadweard Muybridge’s ‘motion pictures’.

In 1892 Ponting’s father, accepting that his eldest son had no enthusiasm for banking, purchased a fruit ranch in northern California for Ponting to run. In early 1893 Ponting, after a stormy trans-Atlantic crossing, travelled by train to the so-called ‘Golden State’, where he cultivated peaches and grapes, prospected for minerals, became a ‘crack shot’ and honed his photographic and mountaineering skills, including in Yosemite. But after Ponting met and married a San Francisco ‘society girl’ and became a father, he sold his fruit farm and the family moved to Sausalito, across the bay from San Francisco.

Ponting now needed to find ways to support his family. Reluctant to return to banking, he followed up the suggestion of a professional photographer and began selling stereoviews to commercial companies and submitting other photographs to illustrated magazines, exhibition organisers and photographic competition promoters. Before long, his expensive hobby became a potential career. After one of Ponting’s photographs was accepted for San Francisco’s first photographic salon, photographer-cum-reviewer Arnold Genthe noted Ponting’s ‘good eye for catching things’, and knack of ‘being ready with his camera at the right moment’. By early 1902 Ponting had published illustrated magazine articles, won several competitions and obtained simultaneous commissions from Leslie’s Magazine and a leading stereoview company to work for them in Asia. Ponting, now thirty-two, was a fully-fledged professional photographer.

So how did Ponting come to go to Antarctica with Captain Scott – and how did it affect his career?

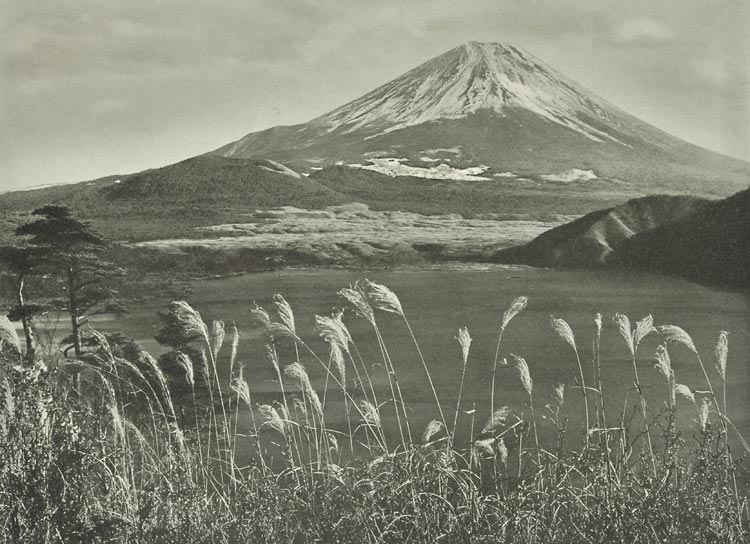

– Ponting made several working visits to Asia, mainly to Japan, which particularly fascinated him and where his photographs of Mount Fuji and other subjects were successfully published in book form. He also covered the Russo-Japanese war for Harper’s Weekly and undertook a working tour of India – but as his long absences from home and preoccupation with his photographic career had irrevocably strained his marriage, he decided to return to Britain rather than California.

By 1907 Ponting was working for several British illustrated magazines and travelling to continental Europe for an American stereoview company. He also secured a solo exhibition at the British Journal of Photography’s galleries and his work appeared in Royal Photographic Society and Alpine Society exhibitions and – thanks to his new friend, photographer E. O. Hoppé – at a prestigious international photography exhibition in Dresden. As the craze for ‘things Japanese’ continued, Ponting began writing a full-length illustrated Japanese memoir, which he planned to publish in time for May 1910’s Japan-British exhibition in London. But when would-be polar traveller Cecil Meares (with whom Ponting had travelled in India) suggested that both he and Ponting apply to join Captain Robert Scott’s second expedition to Antarctica, Ponting met up with Scott. A day later Ponting turned down a more lucrative potential commission and became the first professional photographer contracted to work in Antarctica.

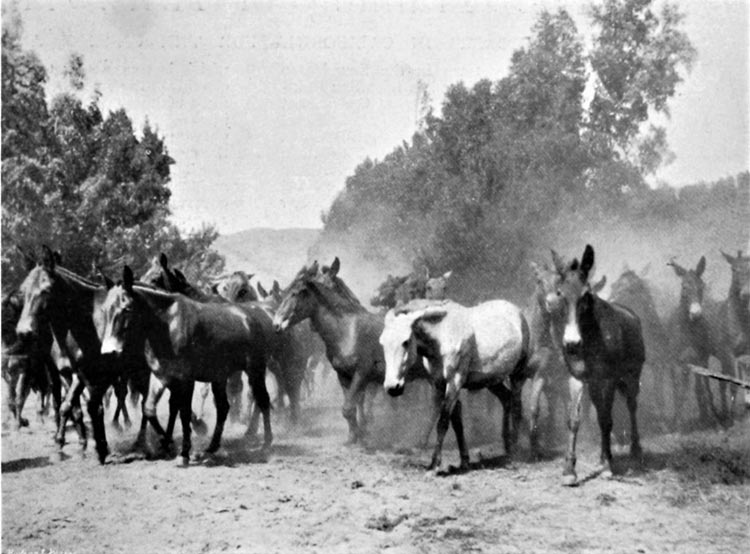

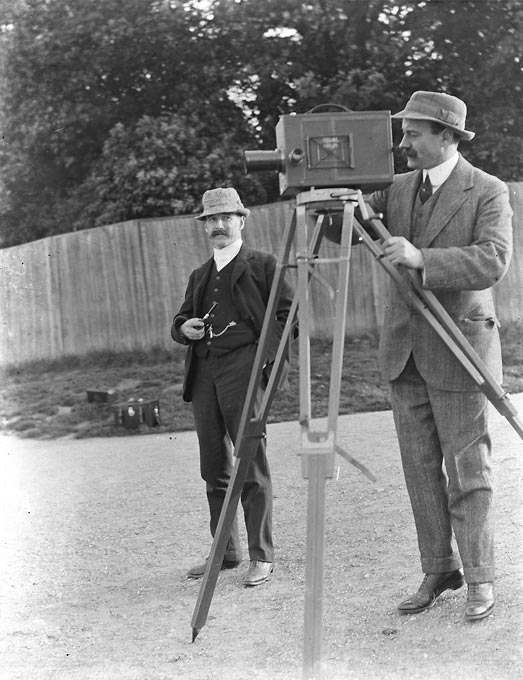

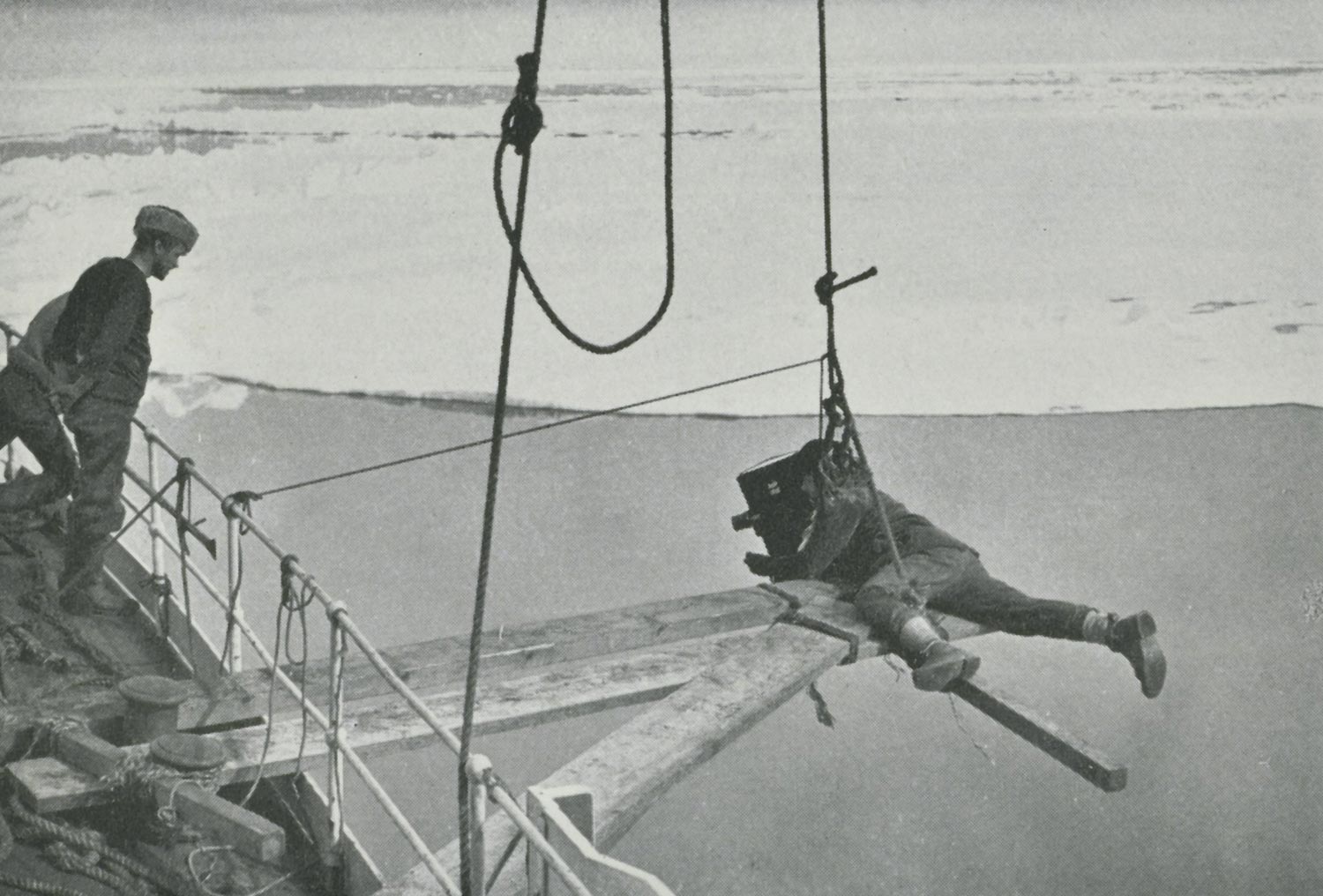

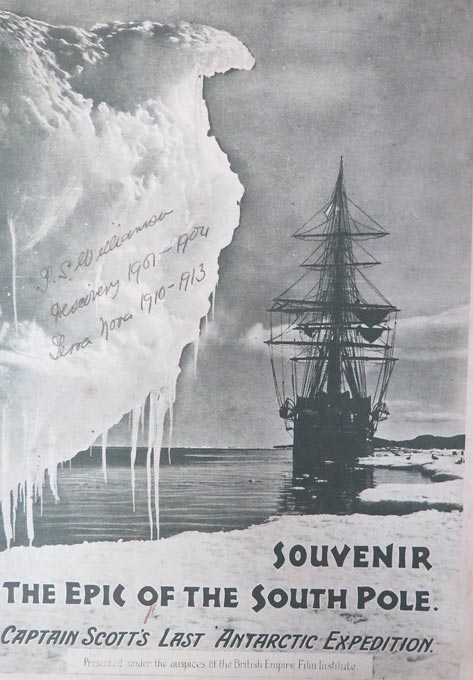

As Scott expected Ponting to take moving as well as still images, veteran camera-designer Arthur Newman trained Ponting on a lightweight kinematograph Newman had adapted to operate in freezing conditions. Between their sessions, Ponting assessed and ordered customised and other photographic equipment and supplies, completed his Japanese memoir and organised exhibits for the Japan-British exhibition. In September, Ponting left London and, by travelling on fast steamers to New Zealand, caught up with Scott, his fellow-travellers and the expedition ship, the Terra Nova. During the voyage down the Southern Ocean, Ponting – between bouts of seasickness – filmed and photographed his companions (human and animal), roped to planks attached to the ship’s side, the Terra Nova cutting through pack-ice.

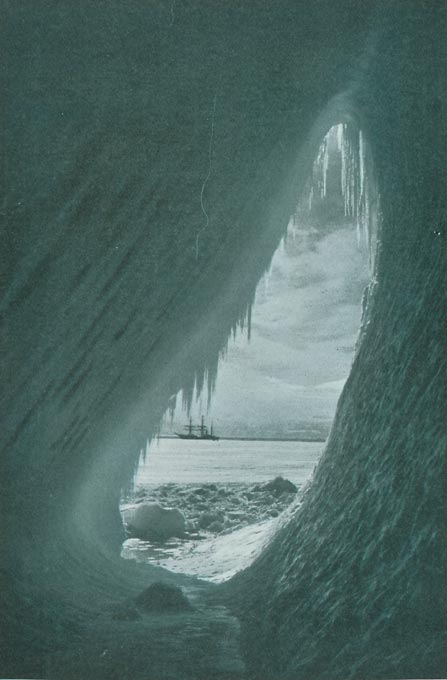

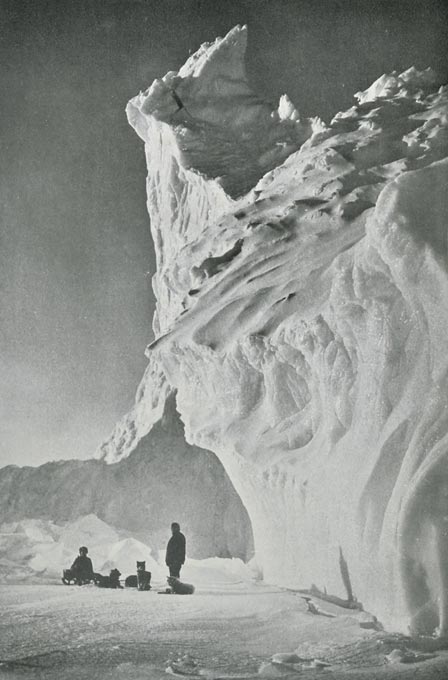

In January 1911, Ponting loaded up a sledge with 200 lbs of photographic equipment and headed across the Antarctic ice, intent on capturing images he which would appeal to Scott, as well as to Gaumont (who would distribute his films) and publications whose sponsorship was vital to the expedition. Ponting’s nerve was regularly tested by unstable ice and close encounters with killer whales, but his early efforts were rewarded by spectacular photographs of a grotto in an iceberg and of Mount Erebus, Antarctica’s equivalent of Mount Fuji.

When the sea showed signs of freezing, the Terra Nova returned to New Zealand with Ponting’s initial batch of films and negatives aboard. As daylight hours reduced with alarming speed, Ponting worked tirelessly, disregarding frost-nipped fingers and loss of skin which froze to metal camera components. From April to August, while the sun remained below the horizon, he developed plates, sorted film strips, organised lantern-slide shows and experimented with indoor and flash photography. Accustomed to travelling and the outdoor life, Ponting found the darkness and life in the hut constraining, but when daylight returned he began showing Scott, Bowers and others who would be travelling south the tricks of his trade, including how to validate their presence at the South Pole by taking photographs using his ‘string and shutter’ technique.

In November 1911 Scott, Wilson and a convoy of men and animals set out south, leaving Ponting to work through lists of wildlife, scenery and other subjects Scott and Wilson wanted him to capture. Ponting then returned to the expedition hut to photograph support teams returning from the southern journey and take delivery of photographic plates and roll-films exposed by Scott and Bowers on the way south. Scott now wanted Ponting to return to London with these and his own films and photographs, so they could be used to encourage people and organisations to make donations towards the expedition’s second season on the ice.

Ponting knew his images could raise more money if Scott could get a message back to base before the ship left, confirming that he and a final small group had reached the South Pole safely – particularly if they were ahead of Roald Amundsen, who was in Antarctica to claim the Pole for recently-independent Norway. But early freezing-over of the sea meant that the Terra Nova reached the expedition’s base late and had to leave earlier than planned – carrying only the news that Scott, Wilson, Bowers, Lawrence Oates and Edgar Evans had been waved off on the final leg of their journey to the South Pole on 4 January 1912.

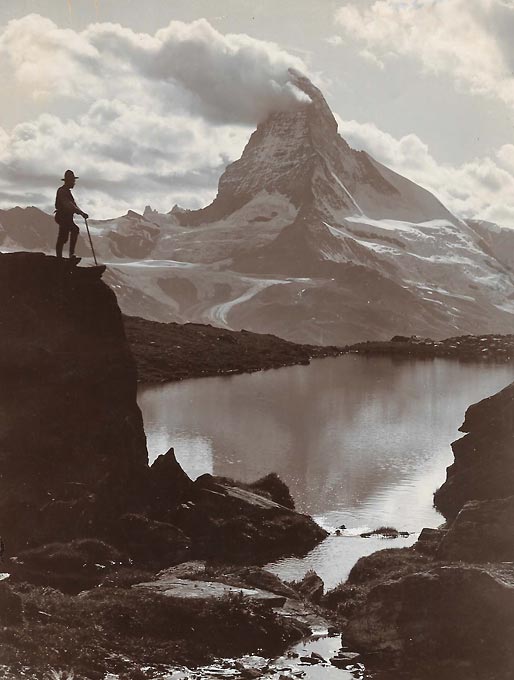

When Ponting and his companions reached New Zealand on 1 April 1912, they learned that Amundsen had reached the South Pole on 14 December 1911. It was a blow, but Ponting duly delivered his films to Gaumont’s Australian representative, then returned to the expedition’s London office, where he prepared for Scott’s return in early 1913. After months of working on photographs, films and lantern-slides, Ponting went on a winter sports holiday in Switzerland – where, in early February, he received a cable announcing the deaths of Scott and his companions on their way back from the South Pole. Distressed and shaken, Ponting returned to London for a memorial service – and discovered that the expedition’s affairs (including his photographs and films) were now in the hands of committees, whose members had greater concerns than verbal agreements Ponting had reached with Scott in Antarctica.

When Ponting had accepted his modest expedition salary, he had hoped his Antarctic commission would open new doors for him. But now, his and Bowers’ images of the South Pole party were more of a memorial than a celebration of a great British achievement. Ponting, who had admired Scott and felt he appreciated Ponting’s work, now mourned lost expedition companions and worried that his professional future was less assured than he had expected.

Much has been written about Ponting over the years but you have dug deep and found both unpublished material and images? What images did you find?

– I ound unpublished material in Britain and overseas, but the most revealing was a collection of letters from Ponting to Arthur Newman – which came with glass negatives showing Newman teaching Ponting how to operate the kinematograph. Auction ‘finds’ included lots containing an original print of Ponting’s photograph of the Matterhorn and original family and other stereoviews, all with handwritten notes on the reverse. One note on a stereoview of Ponting diving into the sea in Sausalito confirmed that Ponting used a string to operate the shutter – the technique he taught Scott and Bowers in Antarctica. I also found, in an archived folder, a long-hidden photograph of Ponting in his favourite open-top Buick. Sadly, I found no sign of Ponting’s Spitsbergen photos and films or photographs of his long-term companion, singer Glae Carrodus – but managed to find examples of both in 1935 publications to use in my book!

You also provide new information on Ponting’s relationship with Frank Hurley, the Australian photographer and filmmaker known for his images of Shackleton’s Endurance expedition.

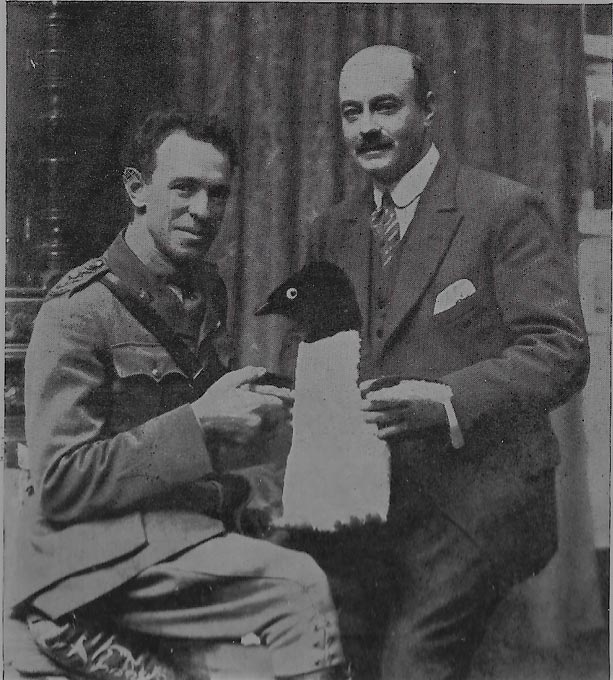

– Although Ponting and Hurley were both in Antarctica in 1911-2, they only met in London in 1916 after Hurley returned from Shackleton’s ill-fated Endurance expedition and came to one of Ponting’s Antarctic cinema-lectures. Hurley was sufficiently impressed by Ponting’s presentation to seek Ponting out afterwards and during several meetings they discussed Antarctic experiences, future plans and the fact that the unforeseen endings of their expeditions meant they had less control over their work than usual. The two self-described ‘brother artists of the trail’ marked their association with a photograph showing Hurley in uniform, Ponting in a three-piece suit and, between them, Ponting’s mascot ‘Ponko the Penguin’.

You also uncovered new information on Ponting’s dealings with Arthur Newman and George Eastman; can you tell me about this?

– In 1935, following Ponting’s death, Newman wrote an obituary for the Photographic Journal, in which he described their long professional and personal association. They initially met when Ponting purchased camera parts from Newman but became friends after Newman invited Ponting to his regular Saturday evening ‘soirées’, where Ponting regularly regaled fellow-guests with travellers’ tales. The two men often had lively, sometimes argumentative, technical discussions about photographic equipment, including Ponting’s own inventions – but also enjoyed driving in the countryside in Ponting’s open-top Buick. Ponting, who rarely mentioned his marriage outside his own family, explained his situation to Newman and admitted to hoping he might eventually afford to divorce and remarry – a confidence which may have encouraged Newman to help Ponting with his inventions and introduce him to Glae Carrodus! In 1943, after Newman died, Photographic Journal used Ponting’s portrait photograph of his friend to illustrate Newman’s obituary.

Turning to George Eastman, Ponting was so enthusiastic about Eastman-Kodak cameras and products that Eastman’s representative in Japan thanked him for boosting his company’s sales there. After returning from Antarctica Ponting sent George Eastman some prints and film-strips made using company products and wrote to Kodakery magazine praising the resilience of roll-film used for the now-famous South Pole photographs. In 1921 Ponting finally met Eastman at a company dinner at London’s Savoy Hotel, where he showed Eastman a prototype of a ‘Kinatome’ home projector Ponting hoped might result in a partnership with the company. Following a spasmodic but long correspondence with Eastman, Ponting asked Newman – a consultant to Eastman’s development laboratories in Rochester – to act as emissary in relation to a scheme which would, Ponting hoped, safeguard his Antarctic photographs and films for posterity. Eastman, by then approaching retirement, politely declined this and other suggestions relating to Ponting’s inventions; their correspondence duly petered out but examples of Ponting’s work remain in the Eastman Museum’s collections.

What did you discover about Ponting’s work in the early British film industry?

During my research I noticed that H.J.P. Arnold and others suggested that Ponting’s post-Antarctic career was, bar his 1921 Antarctic memoir, The Great White South, a series of failures. Renewed interest in Ponting’s photographs and films during the expedition centenary period and my realisation that his films were made against the background of numerous setbacks – Scott’s death, World War I, the post-war depression, Wall Street Crash, Great Depression and advent of ‘talkies’ – suggested that a fresh look at his cinematic achievements was overdue.Ponting’s Antarctic films were released in batches by Gaumont between 1911 and 1913 and shown world-wide, including within variety bills at the London Coliseum and other prestigious theatres. In early 1914 Ponting gave the first of what The Biograph (a film industry trade journal) later described as ‘cinema-lectures’ – an innovative hybrid entertainment combining a precisely-timed lecture script, lantern-slides and film-footage. Ponting also ‘franchised’ his cinema-lectures: while he appeared at London’s Philharmonic Hall, his friend Cecil Meares toured other British venues and other lecturers appeared in Paris and North America.

In 1924, following the success of The Great White South, Ponting released his first full-length film, The Great White Silence, in which lecturers’ commentaries were replaced by intertitles in English and other languages. That was shown worldwide under various titles then, in 1933, as ‘talkies’ became the norm, Ponting produced 90 Degrees South – complete with ‘face-to-camera’ introduction, his own voice-over and a specially-commissioned orchestral soundtrack. Unfortunately, Ponting ran over budget on his last film, which opened during a rare British heatwave in competition with Hollywood ‘blockbuster’ King Kong – but his template of dramatic locations, wildlife interest, eye-witness commentary and ‘behind the camera’ insights influenced Hurley and others and can still be seen today in BBC and other wildlife and travel programmes.

Finally, do you have a favourite Ponting photograph of Antarctica?

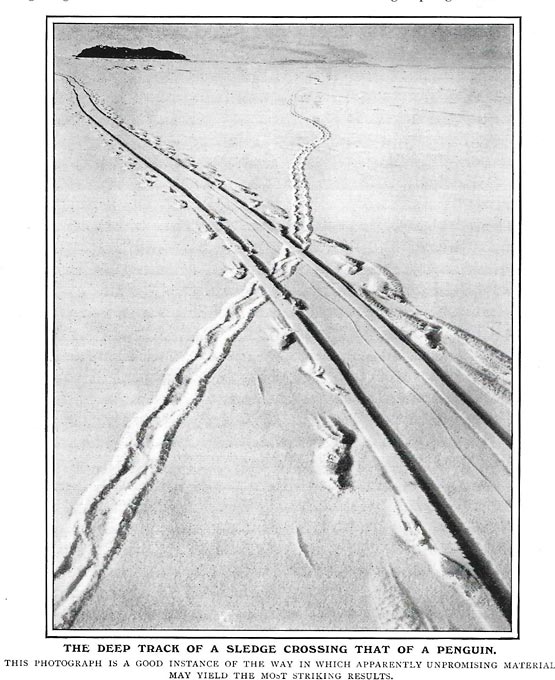

– While many of Ponting’s Antarctic images are well-known ‘classics’, I enjoyed discovering some lesser-known works, including one which I believe was only published once and not exhibited during Ponting’s lifetime. Taken on 8 December 1911, it shows the tracks of Ponting’s sledge crossing those of an Adélie penguin – a ‘less is more’ impromptu composition which Ponting described as ‘an instance in which apparently unpromising material may yield the most striking results.’ What a ‘good eye for catching things’ Ponting had!

For further details see: https://www.thehistorypress.co.uk/publication/herbert-ponting/9780750979016/

All images courtesy Anne Strathie.