I would rather sit on a pumpkin and have it all to myself, than be crowded on a velvet cushion. —Henry David Thoreau

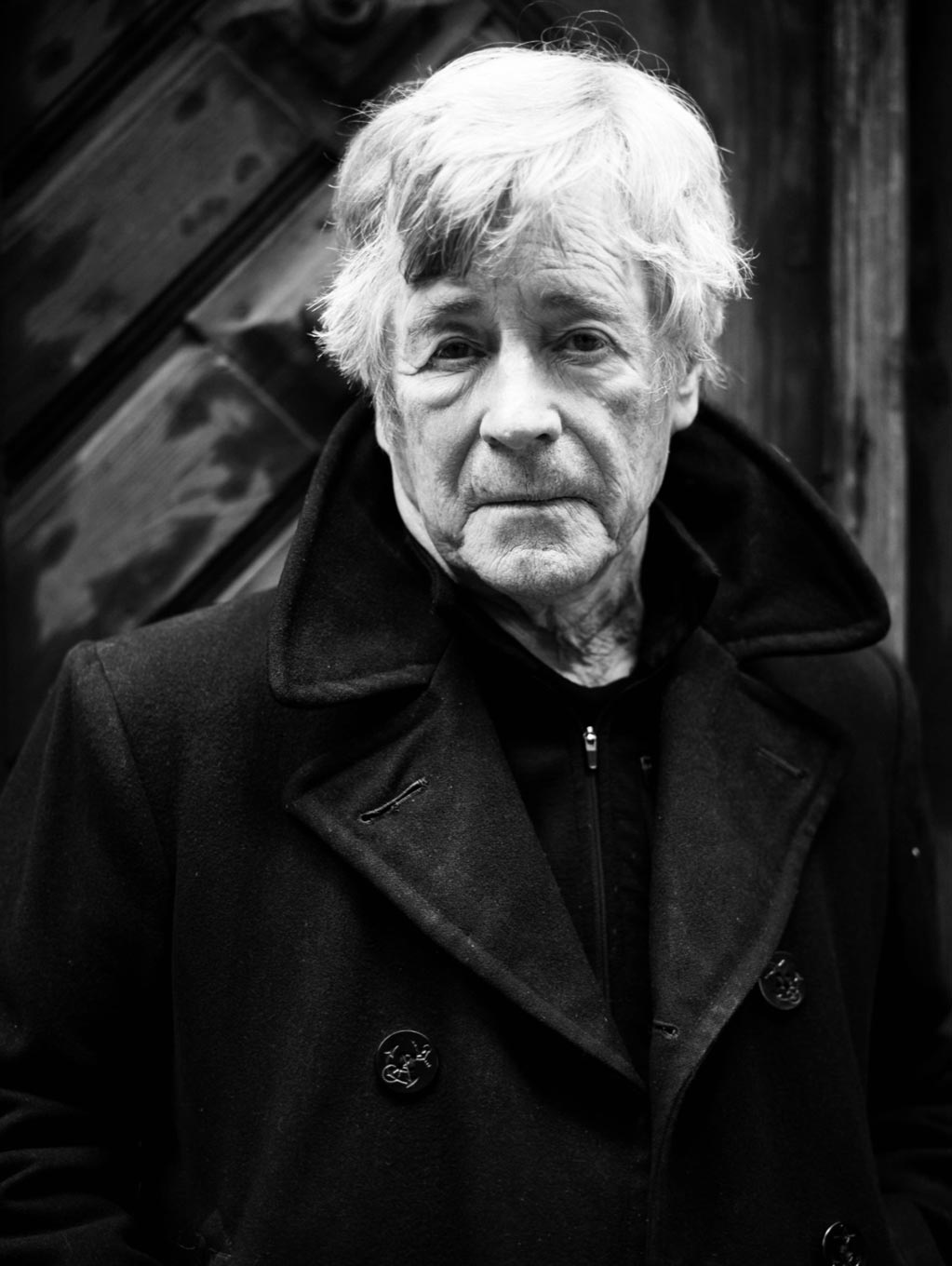

Sean Thackrey (1942-2022), was so well-read that he surely knew F. Scott Fitzgerald’s line, “There are no second acts in American lives.” However, his career proved that this was not always true.

On news of his passing in May of this year there was a universal outpouring of admiration for him as an independent, and innovative winemaker whose tentative beginnings in the 1980’s led to wide renown at the time of his death.

Overlooked or mentioned only perfunctorily were his art world activities—an earlier first act. He was a pioneering dealer in the field of photography just as it was emerging as an important market for collectors, and eventually museums in the 1970’s and early 1980’s.

In 1970, Sean and Susan Thackrey opened a gallery, The Poster, in San Francisco, which later became the Thackrey & Robertson Gallery when Sally Robertson became a partner. In a Victorian on Union Street, down a brick ramp, Robertson hung vintage Art Nouveau posters and prints, and Thackrey focused on rare vintage 19th century photographs. It was a laid-back environment with a little potbelly stove.

Although Thackrey was not a traditional businessman in any of his endeavors, he trusted his intuition and followed it passionately–whatever the cost. In those formative years in the 1970’s, Thackrey saw photography, especially early English works, as beautiful, undervalued, and poorly understood. He set out to specialize in this field. With little capital to purchase stock, he relied on charm, diplomacy, and fierce advocacy for the medium to successfully elicit extraordinary consignments from abroad for exhibitions in his San Francisco gallery.

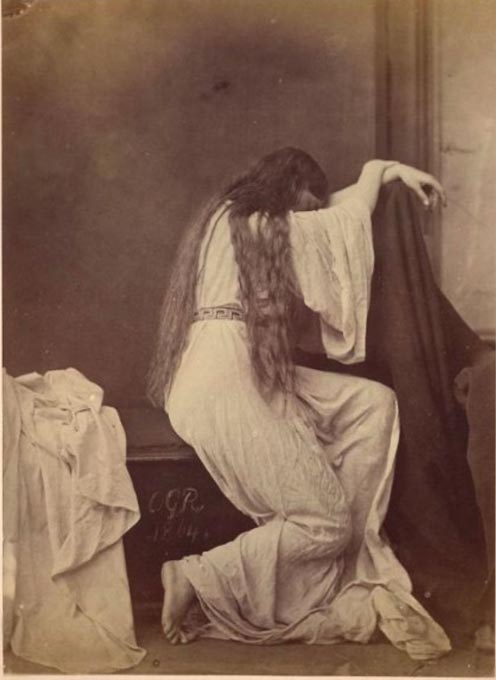

Today, nearly fifty years later, the rarities that passed through the gallery in abundance, often at modest prices, seem beyond belief: fifty Henry Fox Talbot calotypes, fifty Hill & Adamson Calotypes from the Royal Scottish Academy, forty portraits by Julia Margaret Cameron, clichés-verre from the collection of R. E. Lewis, as well as works by Maxime du Camp, Oscar G. Rejlander, Lewis Carroll, Thomas Annan, Peter Henry Emerson, Eugene Atget, Arnold Genthe, Lewis Hine, and August Sander, not to mention surveys of avant-garde Polish and Czech photography and a few contemporary photographers.

Imagine Sam Wagstaff, Robert Mapplethorpe, Simon Lowinsky, Graham Nash, Charles Wehrenberg, and curators John Szarkowski, Weston Naef, Richard Pare, Pierre Apraxine and others from both America and abroad coming through the doors of the Thackrey & Robertson Gallery to view these now rare photographs.

Of his many exhibition titles my favorite was, “Old Photographs for New Collectors: Minor Masterworks of Nineteenth Century Photography.” In our age of ostentation and overstatement, who today would be brave or modest enough to include the word “minor” in the exhibition title? Thackrey would—and did.

Soon after becoming a curator at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, I came under the spell of Thackrey’s belief in the importance of early photography. In my book, “Anonymous,”(2004), I recognized him as one of the six individuals that were crucial in forming my ideas about the nature of anonymous photography. I wrote:

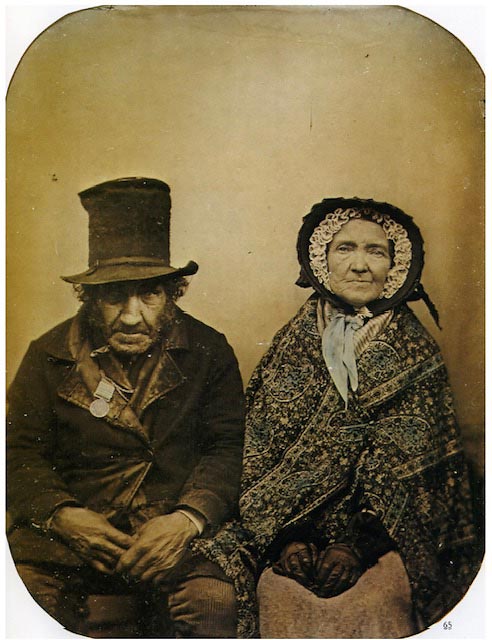

Sean Thackrey was the one who first directed me to the beauty of daguerreotypes and ambrotypes. It was the highly personal nature of these mainly portrait images that attracted him. The fact that they were usually anonymous was of no concern. The presentation of 19th century photography in an almost surreal format of cased imagery, reminiscent of Joseph Cornell, intrigued him and he transferred that fascination to me.

Auctioneer, Philippe Garner, who pioneered photography sales at Sotheby’s Belgravia in the 1970’s remembered Sean:

He was different, his own man, cultured but never ostentatiously so. He was discreet, solid, and correct. He was self -assured in his focus, selective and bold in his purchases. Sean had a strong handshake and a ready smile, was always affable, but we never really socialized. He travelled a long way, further than anyone else to attend my sales and I appreciated that. Sean rode the perfect wave of the photographs market in the Seventies when such great 19th century material was coming to market for the first time.

In those early days in the 1970’s, Thackrey was given the opportunity to build a private collection for William Rubel that reflected his own aesthetic and taste. The fruits of his efforts became one of the most outstanding, and selective assemblages of early photographs of the era.

Richard Pare, the founding Curator of Photography at the Canadian Centre for Architecture wrote:

I remember Sean with great affection and pleasure. There was always a vividness in his approach to life and it was very informative watching the way he went about building the collection for Rubel and his other forays into the auctions…. It took courage to venture in those directions at the time and there were not many in the position of having the qualities in place to make good choices among the vast quantity of material that was appearing at auction in those days. Nobody knew where the market was going, nor did we have any inkling of how scarce the best things were, a fact that has been borne out by the virtual disappearance of the market for much of that material.

The Rubel Collection was first exhibited at the Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento, California in 1982, and in a later exhibition that I curated at the California Palace of the Legion of Honor in San Francisco. Although it emphasized masterworks by early English photographers such as Henry Fox Talbot, Hill & Adamson, and Roger Fenton, it also contained continental practitioners of the era and a number of early 20th century masters. The majority of the Rubel Collection is now in the permanent collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

In the catalogue of the exhibition, “Masterworks of Photography from the Rubel Collection,” Thackrey wrote the following succinct Editor’s Note:

The Rubel collection has been formed with the intent that each photograph it contains should directly touch the spirit and should reward prolonged meditation. Its purpose is contemplative; and if it has a theme, it concerns the nature of photography itself—the human qualities and implications of photographic images, much in the sense of Roland Barthes’s “Camera Lucida”. To accomplish this, we have simply begun at the origins of the medium, working slowly forward through its earliest masters, and through others whose work has seemed as lucid and primary as theirs.

Grief (Hidden Her Face, Yet Visible Her Anguish),1864, albumen silver print.

Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. Gift of John H. Rubel (1985.100.2).

Thackrey began to experiment with wine making on his property in Bolinas in western Marin County in 1979; he registered the winery two years later. He became a legend, “the greatest winemaker in California owning no vineyards.” Sean bought grapes from ancient Napa vines creating such wines as Pleiades, and his iconic Orion. Thackrey’s considerable reputation as a fiercely independent winemaker has been considered in depth elsewhere. By 1995, both Thackrey and Sally Robertson who also lived in Bolinas grew tired of commuting into San Francisco. They closed the gallery in order to better pursue new endeavors—winemaking for Thackrey, and exquisite watercolor painting for Robertson.

Thackrey referred to himself as, “a photographer who made wine”. He pursued photography in his early years winning a competition at age fifteen, and later being active at Reed College. He took advantage of his newfound freedom from the responsibilities of running a gallery to refocus his energy aside from his winemaking, on his own photography. His subject matter was disparate, ranging from the rural landscapes of Bolinas to abstracted minimalist compositions of ancient Roman stonework in Italy. Those works led to museum exhibitions in Bolinas and Berkeley.

On a personal note, Sean was handsome in a way reminiscent of the timeworn appearance of Jack Nicholson in “Five Easy Pieces,” or Harrison Ford as “Indiana Jones.” In over forty years I never saw him in a suit and tie—and his casually rugged fashion sense even earned him a place in the style section of Esquire Magazine! With a self-deprecating sense of humor, he wore a favorite leather jacket emblazoned with “Famous Winemaker.”

His capacity for kindness was exhibited the last time I visited him in Bolinas, when he took the time to feed a baby fox, he had named Bella, that had wandered up to his back door.

Although he never graduated from college despite his attending Reed College and the University of Vienna, the polymath Thackrey nevertheless was conversant in five languages and from 1996 until his death formed the greatest private collection of antiquarian books on the history of viticulture.

Although Sean would not approve, I must label him a “connoisseur.” He was indeed a connoisseur of people—the individuals he chose as friends from all social strata; a connoisseur of history, who assembled and added his own observations to an extraordinary archive of viticulture; a connoisseur of wine, and a vintner of iconoclastic and highly prized vintages; and finally, a connoisseur of photography, the images he made himself, and the 19th century photographs that he championed when few realized their importance.

His contribution to the recognition of photography as an art form should be made known to a new generation of curators, collectors, and dealers. Sean Thackery’s intellectual curiosity and creativity over the years marks a life well lived on his own terms.