This article is an appendix to the article Frames of Mind, published in issue 11 of The Classic. In it, I interviewed Julien Faure-Conorton, a French photography historian, specialising in international Pictorialism, about mounting and framing methods in the movement. We also discussed Art Nouveau in the following exchange.

Pictorialism coincided with Art Nouveau. The style would take on different forms. Jugendstil in the German-speaking countries. In Norway, the so-called Dragon style emerged, with Norse motifs, such as dragons and serpents. Art Nouveau, and variants of it, can be seen in frames used for standard family portraits, but it had little impact on Pictorialist frames.

– Art Nouveau was completely absorbed in Pictorialism. The Pictorialists considered themselves as being part of it, part of what was modern. They adopted the aesthetic, in their books and magazines, as well as in the medals to commemorate their exhibitions. But they didn’t go in that direction for frames. So yes, it is surprising that they didn’t explore Art Nouveau in the frames of their prints.

After the interview with Julien Faure-Conorton, I speculated that Art Nouveau, unlike the Arts & Crafts movement, was disseminated through both luxury items and mass-produced goods. Picture frames would be one of the cheapest ways to buy into the new style, perhaps leading the Pictorialists to shy away from it, regarding it as common, when mounting and framing their works. But that’s speculation.

Still, there are some surviving examples of Pictorialist works in Art Nouveau and Jugend style frames. Mila Palm, owner of the Viennese gallery Milaneum and co-founder the Vienna Vintage Photo Fair, sent me a wonderful example of the latter, a 1901 gum print by Friedrich Baron Hohenbühel, in a roughly cut, square wooden frame, with round carvings added to the corners.

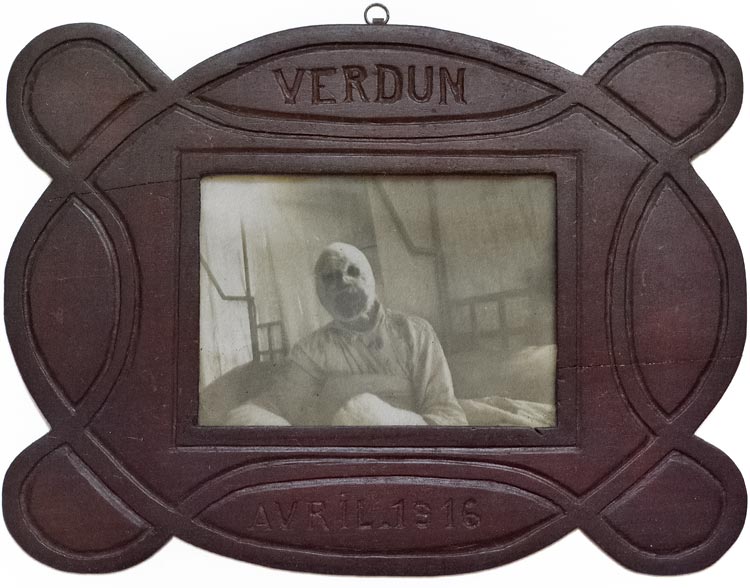

In France, organically rounded Art Nouveau frames proved very popular for portraits. Also, for some very harrowing ones. Such as a work in the collection of Serge Kakou. a photograph of a survivor of the Battle of Verdun in 1916, sitting up in a hospital bed, his head covered in bandages.

Mila Palm sent me an image of elaborate frame, produced in the trenches on the opposing side during the First World War, an example of “Gartenarbeiten”. Palm told me.

– The frame was made from wooden clothespins, otherwise often used to construct crosses of the same size. It’s an example of “Gartenarbeiten”, meaning Trench Works, which were made from everyday objects during war. In the trench warfare of the First World War, many soldiers made souvenirs for relatives back home, from whatever items and materials they had. Bullet casings cartridges were converted into rings, bracelets, pendants, shot glasses, lighters, ashtrays, cigarette tins, candle holders, vases or frames. Grenade fragments were reworked into knives. Wood, mainly coniferous wood, was the most used material in the First World War, as it was needed for the preservation and repair of existing infrastructure and construction of defence structures. The aesthetic of this frame is not far away from the appearance of the trench itself, which was fortified with tree trunks.

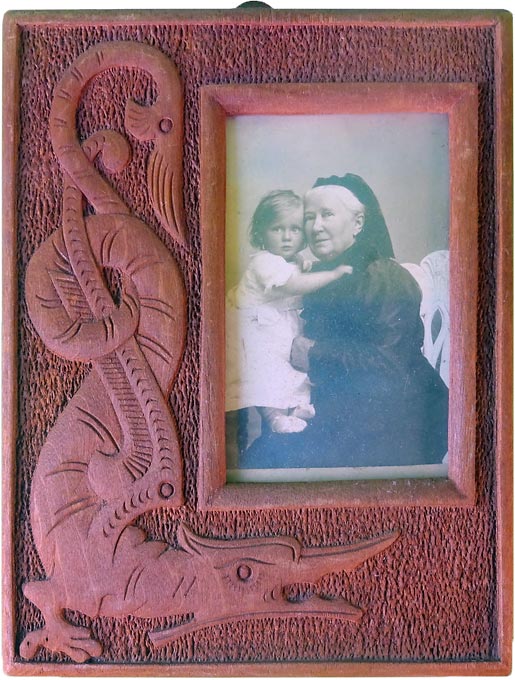

As mentioned in the exchange with Julien Faure-Conorton, Art Nouveau would take on different forms. The Norwegian “Dragestil”, “Dragon Style”, was widely used in Norway from 1880 – 1910. It was carried forward by the surge in Romantic nationalism, and the ever-louder voices demanding independence. Norway had, as a result of the Napoleonic Wars, been annexed by Sweden in 1814, under a common monarch and common foreign policy. Independence was finally won in October 1905.

Dragestil took inspiration from Viking and Medieval art and architecture, including the famous Norwegian “stave churches”, post and lintel constructions in wood. The style embraced old, Norse motifs, such as dragons and serpents. It was used to frame family portraits though not, as far as I have been able to ascertain, by Norwegian Pictorialists.