Joint research by Denis Pellerin and Rebecca Sharpe

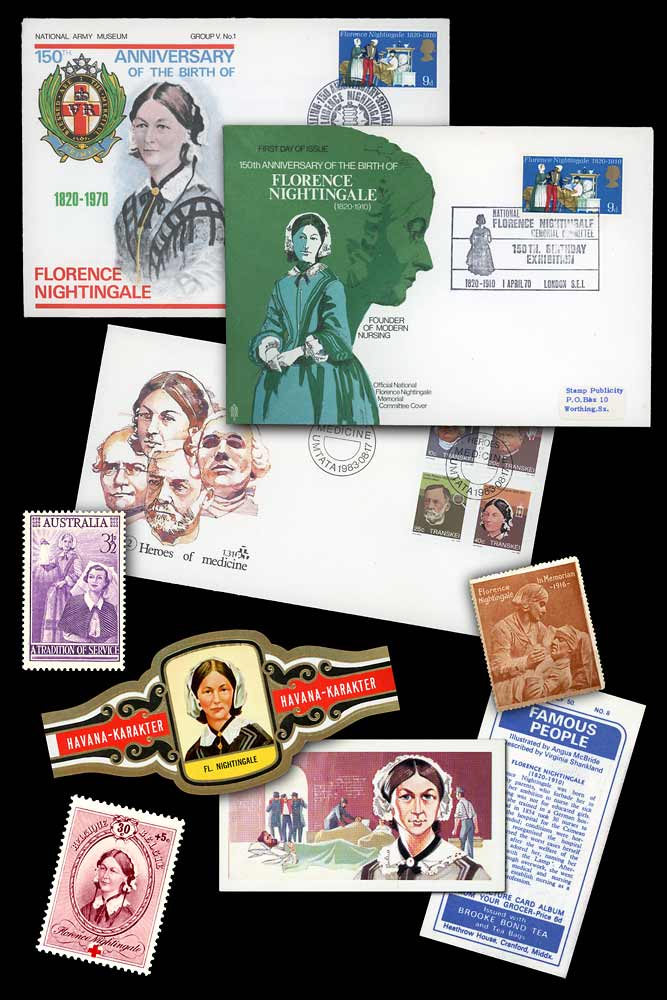

Florence Nightingale apparently loathed having her photograph taken. There are consequently relatively few photographic portraits of her and even fewer around the time of the Crimean War when her name was on every pair of lips; the legend of the Lady with the Lamp was born and the attention of a nation was turned towards a hospital in Scutari, Turkey, where she tended the sick and the wounded. These rare photographic images of Florence Nightingale are so famous and familiar – iconic even – that we take them for granted. Over the years they have been used on stamps, postcards, trading cards, T-shirts, mugs, erasers, cigarette cards, cigar bands (!), etc. Between 1975 and 1994 millions of copies of one of these scant portraits even found their way in everybody’s pockets in the shape of a ten pound banknote issued by the Bank of England.

But what about the photos themselves ? What do we really know about them, about the circumstances in which they were made and distributed and, more importantly maybe, about the photographers who took them ?

This is the story of a quest, of a search that took me and my assistant Rebecca to dozens of different places and archives, both on location and online. Like every quest it had its disappointments and moments of elation, its periods of doubt and its times of excitement. All the questions have not been answered yet and some may never be. But we do know a little more about those images and why they became so popular.

Let’s start with a few facts in order to set the scene and introduce the main protagonists of the story.

Florence Nightingale was born on 12 May 1820, to William Edward Nightingale, born Shore, and Frances, née Smith. She was named after her birthplace, the city of Florence, Tuscany, Italy. Her elder sister, born two years earlier, had also been given the name of the place where she saw the light of day and was called Parthenope, after the Greek colony that occupied the site of present Naples. In 1821 the Nightingale family was back in England where the two sisters were brought up at the family seats of Embley, Hampshire, and Lea Hurst, Derbyshire. In September 1837, William Nightingale took his family on a nineteen-month tour of Europe where they successively visited France, Italy and Switzerland in a leisurely way. Later, Florence would continue her travels, notably to Rome, Greece and Egypt, with her friends Charles and Selina Bracebridge. In 1844, despite strong opposition from her whole family, Florence announced her intention of entering the nursing career. She studied hard and received four months of medical training at the Institution of Kaiserwerth on the Rhine, run by Lutherian Pastor Theodor Fliedner (1800-1864) for the training of deaconesses. In August 1853, Nightingale became the superintendent of the Institute for the Care of Sick Gentlewomen in Upper-Harley Street, London.

The Crimean War, which had started in October 1853 between Russia and the Ottoman Empire, took a new turn in March 1854 when Britain and France, fearful of Russian expansion, forgot centuries of enmity and jointly declared war on Russia. They were joined in May 1855 by Sardinian troops. The first great clash of the Crimean War, the Battle of the Alma, took place on 20 September 1854, just days after the French and British troops had disembarked, with many men already sick with cholera. There were heavy casualties on both sides (over 8500 soldiers altogether) and it was soon realised that nothing had really been planned to take care of the wounded, a large number of whom had to wait days before they could sail to the Scutari hospital in Constantinople. Reports soon reached Britain about the terrible conditions in which the sick and the wounded were looked after. Sydney Herbert (1810-1862), who was responsible for the Crimean War at the War Office and who had been a close friend of Florence Nightingale since 1847, after they had met in Rome, gave her permission to sail to Turkey. On 21 October 1854, Florence Nightingale, left Britain with thirty-eight volunteer nurses she had personally trained (among whom was her aunt Mai Smith) and 15 Catholic Nuns that had been added to the contingent, against Florence’s wishes, by the Archbishop of Westminster, Henry Edward Manning.

It is very important to bear in mind that when she sailed for the Crimea, the name of Florence Nightingale was totally unknown to the general public. Queen Victoria herself had only heard mention of her a few days prior to her departure and knew very little about her. She wrote in her Journal on the evening of the 18th of October 1854: “The Duke [of Newcastle, Secretary of War] told us he had settled to send out 30 Nurses for the Hospitals at Scutari & Varna, under a Miss Nightingale, who is a remarkable person, having studied both Medicine & Surgery & having practised in Hospitals at Paris & in Germany.” The first articles mentioning her name (Illustrated London News, 21 October 1854, for instance), call her Mrs. Nightingale until the Oxford Chronicle and Reading Gazette published a piece entitled “Who is Mrs. Nightingale ?” in its 11 November 1854 issue, revealing her unmarried status and a fair amount of facts about her:

WHO IS MRS. NIGHTINGALE ?

Many ask this question and it has not yet been adequately answered. We reply, then, Mrs. Nightingale is Miss Nightingale, or rather Miss Florence Nightingale, the youngest daughter and presumptive co-heiress of her father, William Shore Nightingale, of Hembley Park, Hampshire, and the Lea Hurst, Derbyshire. She is, moreover, a young lady of singular endowments, both natural and acquired. In a knowledge of the ancient languages and of the higher branches of mathematics, in general art, science, and literature, her attainments are extraordinary. There is scarcely a modern language which she does not understand; and she speaks French, German, and Italian as fluently as her native English. […]

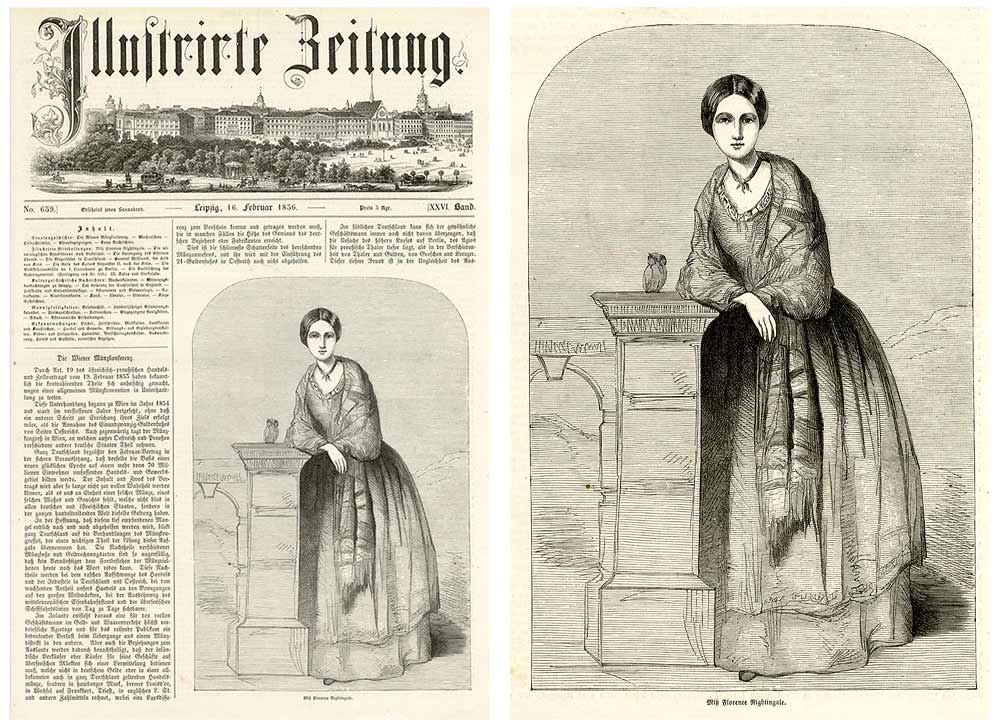

Soon however words were not enough for the public who wanted to see for themselves what this extraordinary young person looked like. As early as November 1854, the firm Paul and Dominic Colnaghi and Co., 13 and 14 Pall-Mall, were issuing two portraits of the young woman, lithographed by R. J. Lane, Esq., A.R.A. from sketches by Florence’s cousin Hilary Bonham Carter (1821-1865).

In January 1855, it was the turn of The Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine, published by Messrs. Clarke and Beeton, to offer their readers “a portrait of that true heroine, Florence Nightingale.” On 3 February, the Weekly Gazette issued “a portrait of Miss Nightingale, and a view of the landing of the wounded at Scutari.” On 10 February Cassell’s Illustrated Family Paper also had a woodcut of Miss Nightingale to show its readers (see illustration). In June 1855 the third “and cheap” edition of The History of Woman, by S. W. Fulton, included a portrait of Florence Nightingale.

These “likenesses”, however, were merely sketches, lithographs or woodcuts, as untruthful as the portraits of the Queen or of any other celebrities of the time printed in the same way.

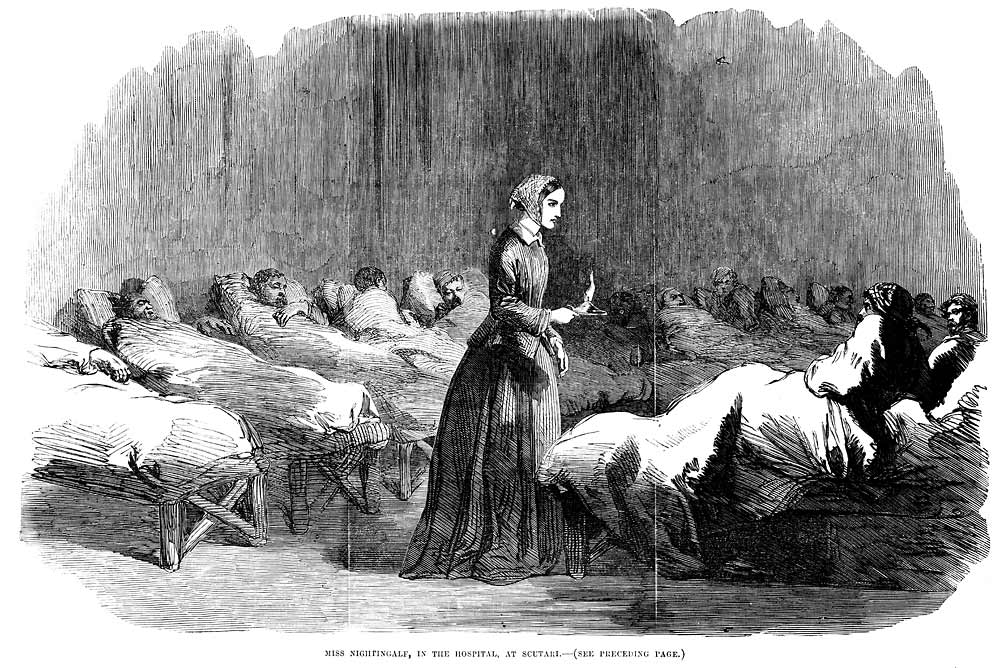

Florence reached iconic status thanks to a letter published in The Times by John McDonald on 8 February 1855, an extract of which was reproduced in the Illustrated London News on 24 February accompanied by a woodcut that firmly branded in the mind of a whole nation the image of the Lady with the Lamp :

She is a ‘ministering angel’ without any exaggeration in these hospitals, and as her slender form glides quietly along each corridor, every poor fellow’s face softens with gratitude at the sight of her. When all the medical officers have retired for the night and silence and darkness have settled down upon those miles of prostrate sick, she may be observed alone, with a little lamp in her hand, making her solitary rounds.

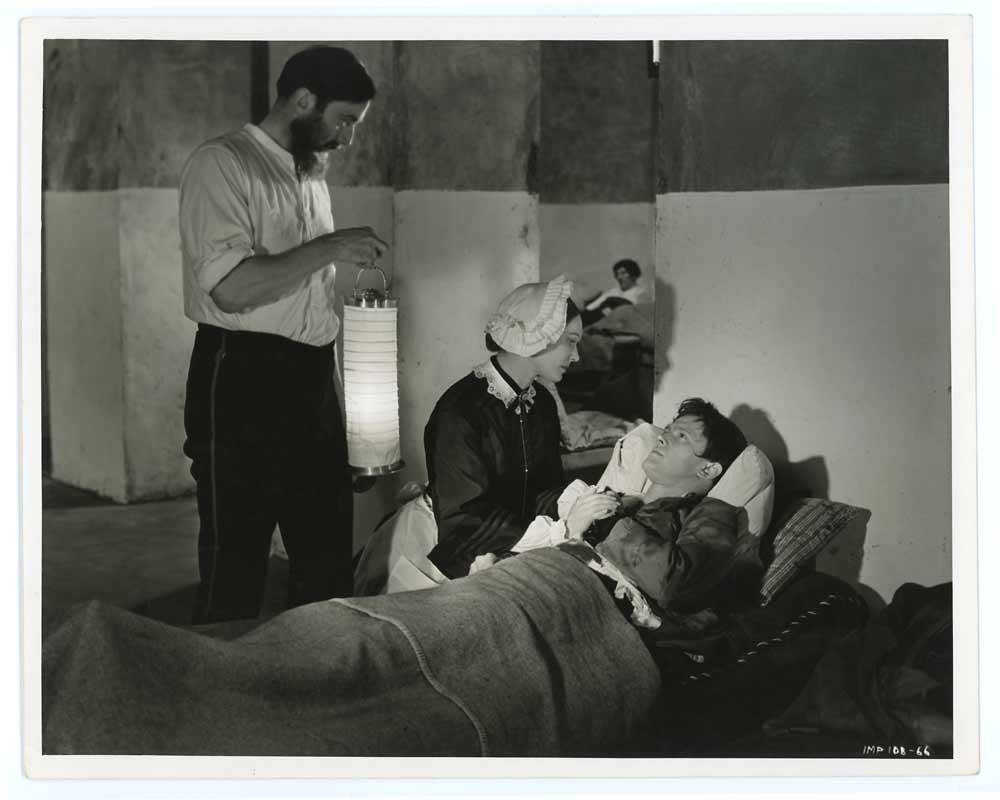

The artist responsible for the woodcut in the ILN never dreamt that he was instrumental in creating a myth and, at the same time, making a mistake that would be reproduced over and over again for decades to come. Most representations of Florence in her character as the Lady with the Lamp – an expression which reached cult status in 1857 when Henry Wadsworth Longfellow included it in his poem Santa Filomena – show her holding a genie lamp, one that is also known as a Greek oil lamp. We actually know, from objects brought back from Scutari and now on display at the National Army Museum, London, that she was using a paper lantern of the kind shown in our illustration. Oddly enough, a 1951 film, The Lady with a Lamp, starring Anna Neagle in the leading part and Michael Wilding as Sydney Herbert, features her using a paper lantern. Somebody had obviously done their homework.

After the articles in The Times and the Illustrated London News Nightingale’s fame grew fast. Though she never craved for attention herself, she certainly got a lot of it, not to mention media coverage. Songs and poems were dedicated to her or composed about her, stories of her dedication and kindness were reported in the press but the public could still not satisfy their curiosity as to what she really looked like. Photos of the Crimean War by Roger Fenton, who stayed in the Crimea from March to June 1855 and brought back some 350 large format negatives, had been exhibited in London as early as September and made some of the faces of the soldiers and officers familiar with the public, but Florence’s portrait was not among those exhibited. Hers and Fenton’s paths could have crossed though as her first visit to the Crimea was made in May 1855. She landed at Balaclava on 5 May and set to work immediately but after a couple of weeks fell victim to the “Crimean fever” and was soon at death’s door. She got a little better, however and agreed to sail back to Constantinople to recover her strength, thus missing the opportunity to be photographed by Fenton. There were other “drawn” portraits of her published before her return to Britain, one of the most popular ones by her sister Partenope, showing a young Florence with her tiny pet owl, Athena, whom she had rescued during her stay in Athens (see illustration). Florence herself reported that the owl, notable for her irascible character, died on the day she left for the Crimea. Her body was left with a taxidermist and Athena is now to be seen in a display case at the Florence Nightingale Museum, London (see illustration)

The Crimean war ended soon after the fall of Sevastopol on 8 September 1855 and on 30 March 1856 the Treaty of Paris was signed, which put an official end to the conflict. By then troops had started returning to England but Nightingale was still tending the wounded in Scutari. It was then that publisher Thomas Agnew, who had previously sponsored Fenton’s photographic trip to the Crimea decided to send there the young artist Jerry Barrett who wished to paint a companion piece to his Queen Victoria’s First Visit to her Wounded Soldiers and had decided on a composition featuring Florence Nightingale. Barrett and his travelling companion Henry Newman arrived at Scutari in May but did not meet Florence Nightingale until July. The three interviews Barrett had with the portrait-loathing Florence on 7, 8 and 13 July all ended up with a flat refusal from the lady to sit for him. As a last recourse, Barrett appealed one more time to her in a letter. His friend Newman recorded that Barrett’s intentions were to “carry on the attack in England through some influential quarters” should Nightingale persist in refusing to sit for him. Florence’s answer to Barrett’s plea, written on 18 July, is worth reading through as it explains a lot about Nightingale’s attitude towards similar requests throughout her life :

“Your statement of my having caused you serious inconvenience by declining to sit for your picture cannot but cause me distress. As, however, I declined from no want of willingness to forward your wishes, but from a principle which I had very fully considered & which indeed had been forced upon me by the experience of the whole time during which I have been engaged on this work, I think you will see that to give a different answer to your request than the one I have already given is impossible to me. I repeat that to hear that this answer causes inconvenience is painful to me – although I have had no share in causing any such disappointments, for my answer would have been the same before your coming out as now, had the request then been made. I must also repeat that publicity has been the cause of the greatest draw-backs I have experienced in the prosecution of the work committed to my charge – & that it is in consequence of this conviction that I have determined in no way to forward the making a show of myself or of any person, or thing connected with that work, though I cannot always prevent them or me being made a show of.” 1Letter from Florence Nightingale to Jerry Barret, dated 18 July 1857. London Metropolitan Archives. LMA/H01/ST/ NC /03/SU/E/193

Barrett had to make do with but a few hasty sketches he had drawn of Miss Nightingale without her knowledge on the rare occasions he had sighted her. 2The National Portrait Gallery have in their collection a sketch made by Barrett in June 1856 (NPG 2939) and another one made on 27th July (NPG 3303) As for Florence’s aversion to making a show of herself it was evidenced again less than two weeks after she wrote to Barrett. When she left Scutari at the end of July, she was offered passage on board a British man-of-war but turned down the offer and chose to embark on a French vessel, the Danube, bound for Athens, Messina and Marseille. She travelled incognito with her aunt under the name of Miss Smith, took trains across France from South to North, crossed the Channel, and spent a night in London before making her way to Derbyshire – where she arrived on 7 August 1856 – without being recognised once from the day she left to the time she found herself on the platform of the station closest to her home. This stealthy return was noted by the press. “Miss Nightingale,” wrote a journalist from the Globe on 12 August 1856, “sedulously avoided that public welcome which would have greeted her had the day or place of her landing in England be made known.”

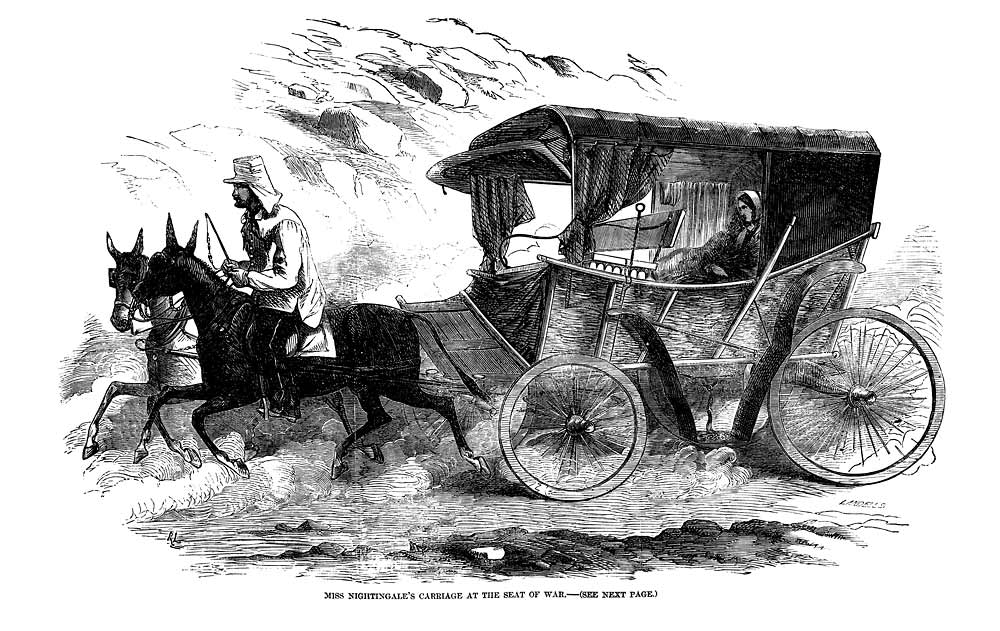

The disappointment and frustration felt jointly by the public and the press – who were equally deprived of giving Florence a hero’s welcome and of seeing, at last, what she really looked like – did not last long. Since the “ministering angel” would have none of the public’s admiration and gratitude these were quickly vented on the makeshift carriage that she had used in the Crimea for her rounds and which arrived in Southampton – on board the steamer Argo – on 14 August 1856, a week to the day after its owner’s home coming. Florence’s carriage was first written about in a Southampton paper, the Hants Independent, and soon every newspaper in Britain reproduced the descriptive paragraph they had published. On 30 August, the Illustrated London News, followed suit but added an engraving representing the said carriage “in action” with a sketch of its user sitting in the back. In the absence of any new sketch or of any photograph of the public’s favourite person, that was the best they could do. The carriage soon became a much admired relic. After Florence’s death, it was given to the Chesterfield Museum by the Nightingale family. In turn, the Museum gave it to St. Thomas Hospital in November 1930. The carriage was heavily damaged during an air raid in December 1941 but was speedily restored to its former glory. It took part in several fund-raising pageants over the years, the most recent one being held on the centenary of the Crimean war in 1954. In storage for years, it is now on display at Claydon House, a National Trust property that once belonged to Florence’s sister’s husband, Sir Harry Verney.

After a few weeks’ rest among her family, Florence Nightingale made her way to Balmoral, where she met the Queen and Prince Albert on a couple of occasions between 21 September and 6 October 1856. By mid-October she was back at Lea Hurst, then journeyed to London where she arrived in early November to stay at the Burlington Hotel in Old Burlington Street. Except for a visit to her father’s residence in Hampshire in January, a fortnight in Edinburgh in April and a couple of weeks in spring where she went to see her uncle and aunt Smith, Florence Nightingale spent a good part of the first half of 1857 in London. This will soon prove to be an important piece of information. On 3 July 1857, Jerry Barrett, who had finished the painting showing Queen Victoria’s First Visit to Her Wounded Soldiers at Chatham Hospital, wrote to Agnew 3Handwritten letter from Jerry Barrett to Thomas Agnew, dated 3 July 1857 and pasted in a scrapbook relating to the painting Queen Victoria’s First Visit to her Wounded Soldiers. National Portrait Gallery, London. NPG46/63/2/1/1 not only to mention the Queen had still not seen it but also to let him know he had been working hard on the Scutari picture. The Bracebridges, Miss Tubbet, Alexis Soyer, and others, who had all been at Scutari and were therefore featured in the scene, had sat for him. In his letter, Barrett also refers to a couple of visits by Mrs Nightingale, Florence’s mother and to her commendation of her daughter’s likeness. Barrett then hints at a visit from “a very intimate friend” of the above mentioned sitters. This mysterious person who cannot be named could be Florence herself, but there is no evidence in that document, or in any other for that matter, that she sat for him. How then could the likeness be so good ? I have a theory about that which I will explain soon. By the time the painting was completed (end of June, beginning of July 1857), few people had seen it and therefore knew what Florence looked like. The finished canvas was bought by Agnew in August and was immediately put into the hands of printmaker and draughtsman Samuel Bellin (1799-1893) who had been chosen to engrave it. It was not exhibited until May 1858 at the gallery of Hayward and Leggat, in the City of London. The press made it clear that the heroine had refused to sit for the artist and lauded him for having achieved such a faithful likeness, 4London Daily News, Thursday 13 May 1858, p.2: “FLORENCE NIGHTINGALE AT SCUTARI.” – A highly interesting picture has just been finished by Mr. Barrett, and is now exhibited at the gallery of Messrs. Leggatt, Cornhill. […] With characteristic unostentation and retiring delicacy, she has never consented to give a formal sitting, but we are happy to believe that she was not averse to sanction this pictorial presentment, which will answer many a chastening recollection of love and gratitude. The artist has, under this disadvantage, nevertheless been successful with the likeness. Before Barrett’s painting was hung on the walls of that gallery the curious public still had to resort to written descriptions of Florence, like the following one, reproduced in the Sussex Adviser in its 20 October 1857 issue, from Alexis Soyer’s newly-published book Soyer’s Culinary Campaign. Being historical reminiscences of the late war:

FLORENCE NIGHTINGALE (HER PORTRAIT). – She is rather high in stature, fair in complexion, and slim in person; her hair is brown, and is worn quite plain; her physiognomy is most pleasing; her eyes, of a bluish tint, speak volumes, and are always sparkling with intelligence; her mouth is small and well formed, while her lips act in unison, and make known the impression of her heart – one seems the reflex of the other. Her visage, as regards expression, is very remarkable, and one can almost anticipate by her countenance what she is about to say; alternatively, with matters of the most import, a gentle smile passes radiantly over her countenance, thus proving her evenness of temper; at other times, when wit or pleasantry prevails, the heroine is lost in the happy, good-natured smile which pervades her face and you recognise only the charming woman. Her dress is generally of a greyish or black tint; she wears a simple white cap, and often a rough apron. In a word, her whole appearance is religiously simple and unsophisticated. – Soyer’s Culinary Campaign

The engraving after the painting was published in January 1860 and kept alive the legend of the Lady with the Lamp. It was a good thing – and a profitable one for Agnew who owned the copyright – since the original composition soon disappeared from public sight. After touring the country for several months in 1858 it was bought by a private collector the following year, only to be publicly displayed again in 1993, after its purchase in an auction by the National Portrait Gallery. A reviewer from the Liverpool Mercury wrote on 14 December 1858, when Barrett’s canvas was on display at Thomas Agnew’s gallery in Liverpool, that “the portrait of Miss Nightingale is pronounced on good authority to be perfect”, while his colleague from the Downshire Protestant concluded three days later that “a more perfect portrait of Miss Nightingale was never drawn.” This brings us back to the question of how Barrett managed to get such a faithful likeness without any sitting. The answer is simple – photographs – but the story behind those photographic images, far from being straightforward, is shrouded in mystery and confusion, a confusion Florence herself helped to spread.

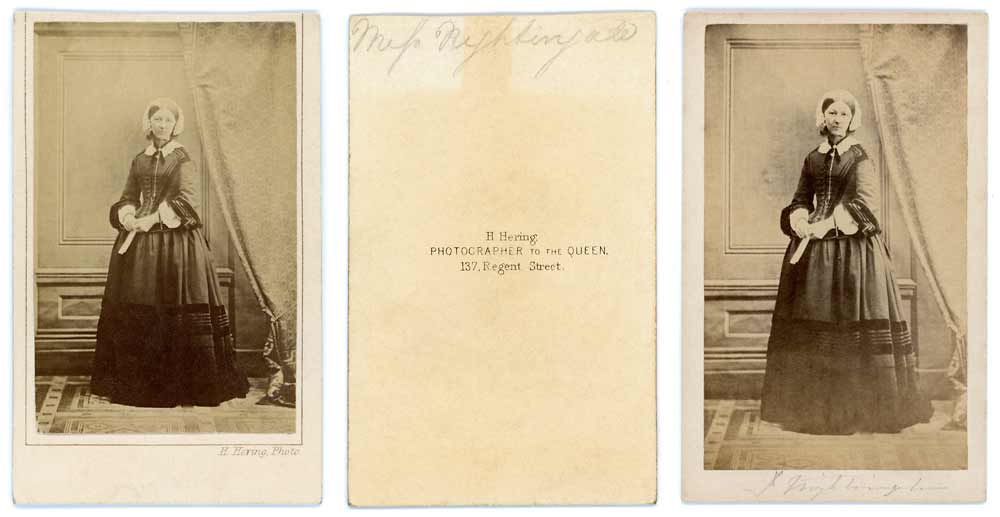

All her life Florence Nightingale stuck to the same story, namely that she had sat only once for her photograph, and that by command of Queen Victoria herself, intimating thereby that she could not but obey. We know the story to be a lie since the few photographs of Florence Nightingale around the time of the Crimean War suggest there were at least four different sittings over a period of several years. So why did saintly Florence lie ? It seems that she adopted this line of defence in order to be left alone and to be able to reject any request for her portrait. The message was clear: only a royal command could make her sit for her portrait. And as everybody knows, a lie often repeated tends to become truth even to the person who has first uttered it. We have written evidence of Florence’s trite response to any photographic request. “I am very grateful to you for your most kind letter of July 9”, she wrote to Mrs. Walker on 3 September 1866. “As you have honoured me with a request for my Photograph, I made enquiries in order not to seem ungracious. But, till now I have never but once given it, not thinking it worth anybody’s acceptance – and that once was the Queen’s – and that is the only ‘once’ I have ever sat for it viz, by command, which I could not help.” 5Typed copy of a letter to Mrs Walker, dated 3 September 1866. London Metropolitan Archives, LMA/H01/ST/NC/05/003/024

On 1 December 1868, her ally in attempting to reform workhouse infirmaries, Dr. William Rendle, got a very similar answer when he made the same request: “I would send you a photograph if I had one,” Florence wrote. “As you devine from this I have not. I never had one done, except once by command. I have a superstition, as far as myself am concerned, against “images made with hands” — & would rather leave no memorial of myself either of name or anything else but only of God, whose unworthy servant I am.” 6Handwritten letter from Florence Nightingale to Dr. William Rendle, dated 1 December 1868. London Metropolitan Archives LMA/H01/ST/NC/01/003/68/14

Finally, in February 1911, nearly a year after her death, Elizabeth Robinson Scovil, an American nurse and writer about nursing, published in The American Journal of Nursing, an account of a visit she made to Florence Nightingale on 30 March 1897:

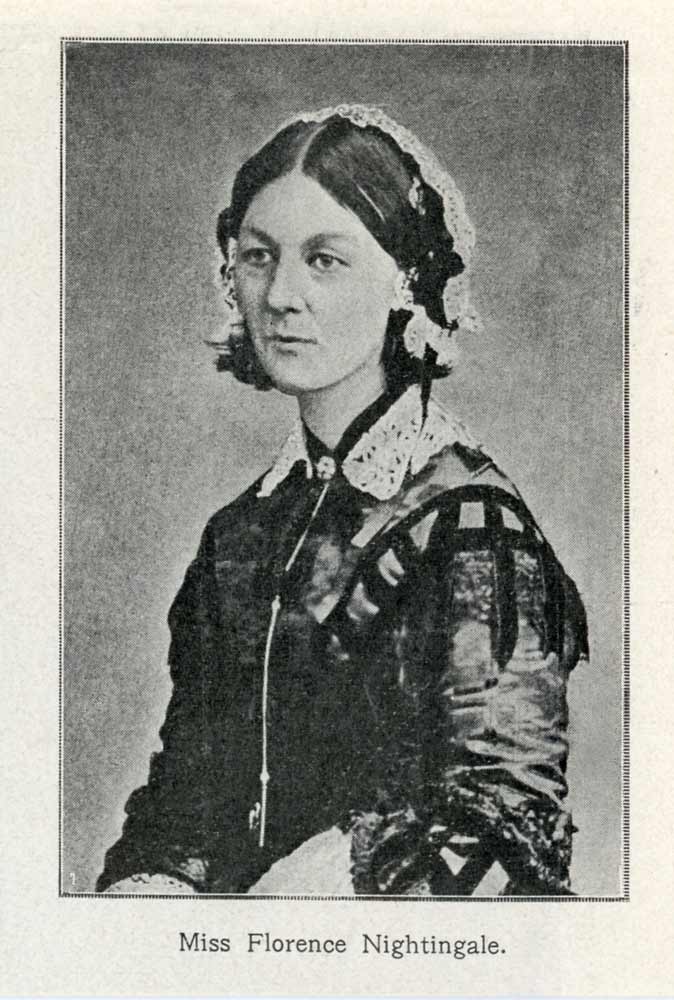

I had bought one of her photographs at the rooms of the London Stereoscopic Company the day before and I wanted very much to get her autograph on it, so drawing it from my bag I proffered my request. She took the card, glanced at it, and laying it down, said, “I always disliked having my photograph taken. This one was done by command of the Queen when I returned from the Crimea.” It was the one that is usually reproduced, showing her in a black lace cap, with rosettes over the ears. I said, “I have seen a very excellent and more recent photograph of you, Miss Nightingale.” “I don’t know when they got it, the villains!” she said with a smile.

After a few minutes she took the card up again, and twirling it in her fingers, said, “If I write my name on this, people will think I gave it to you.” Seeing that she really did not want to do it, I bethought me of my birthday book, which I carried with me, and said, “ Well, Miss Nightingale, if you won’t write your name on the photograph will you in my birthday book? ” She gave me a whimsical glance, a flash of the eyes which I have never forgotten, said, “ Oh, you monkey,” and wrote the coveted words. 7Elizabeth Robinson Scovil (1849-1934), The American Journal of Nursing, February 1911, Volume 11, Issue 5, pp. 365-368. “PERSONAL RECOLLECTIONS OF FLORENCE NIGHTINGALE”

We also know, from reproductions of images in public and private collections, that, despite her apparent reluctance and what she said to Miss Scovil, Florence Nightingale signed copies of all of her known iconic photographs. She must therefore have been fully aware they were being sold and distributed. What seems to be the earliest signed one bears Florence’s signature on the front and the date of 1861 on the back. It is currently on display at the Florence Nightingale Museum in London 8I have some doubts the image was actually signed in 1861 as it bears the mention “registered” and that particular photograph (a vignette of Florence’s head and bust) was not entered at Stationer’s hall until July 1866. The date most likely refers to the delivery of the certificate that has been framed with it. Whatever the date it was signed, however, it is clear Florence Nightingale autographed that image at some point and was definitely aware it was available for sale. The Auchincloss collection, in the United States, has a different image with Florence’s signature and the date 1867 written on it. There are also several other signed copies, without dates on them.

It is high time to examine the photographic portraits we have of Florence Nightingale and the little we know about the circumstances in which they were taken. There are altogether eight photographs of the Lady with the Lamp but only seven from the three sittings out of which the main three iconic images of Florence come from. The earliest photograph, showing a very young Florence reading a book was taken in Germany around 1852 and later published as a carte-de-visite by Julius Cornelius Schaarwächter from Berlin 9[You can see this image on the Wellcome collection website: https://wellcomecollection.org/works/pqrwg3wf/images?id=ebwyy774 Schaarwächter, being born in 1847 cannot be the author of the image as he was only five when it was taken. He is just a later distributor, as a lot of the people who will be mentioned here. The name of the artist responsible for this early portrait unfortunately remains a mystery.

The remaining seven images have been successively attributed to Albert Edward Coe, Richard Keene of Derby, Goodman, also of Derby, another Goodman, without mention of his whereabouts, the London Stereoscopic Company, Henry Hering, William Edward Kilburn, and Henry Lenthall, all four from London. Depending on the collections where they are now housed the dates they are supposed to have been made at span over eight years, from 1854 to 1862.

First of all there was no photographer called Goodman in Derby, which allows us to get rid at once of one of the contestants to the role of photographer to Florence Nightingale. There was, however a Richard Keene in Derby. He was born on 25 May 1825 in Bethnal Green, Middlesex, and died in Derby on 13 December 1894. He owned a repository of Art at Iron Gate, Derby, where he regularly displayed famous paintings. In 1860 he exhibited in his premises a copy of Barrett’s The Mission of Mercy. Florence Nightingale at Scutari. Keene was a dealer in stereoscopes and stereoscopic views and groups. He was a photographer too and took portraits which were then issued as cartes-de-visite. However he did not photograph Florence Nightingale. The photo of her which is attributed to him was taken by another person.

Albert Edward Coe was born in Norwich, Norfolk, on 24 September 1843, the son of Edward Coe, compositor, and of his wife Elizabeth. He was only twelve when Florence returned from the Crimea and, again, cannot be the author of any of her photographs. He is described as a pupil teacher in the 1861 census but by 1871 he had given up teaching – I can totally understand that – and was already a photographer. He was still listed as a photographer in the 1911 census and died on 3 August 1928 in the city he had never left, Norwich. Like a lot of his colleagues, he published photos of Florence Nightingale bearing his name but is certainly not the photographer.

Henry Hering first saw the light of day in 1814 in London. He was born into a family of bookbinders, booksellers and publishers and was admitted as a partner of the family business in 1836. In 1843 he went into partnership with a Henry Remington as booksellers and printers and the following year they moved their headquarters to 137 Regent Street. The partnership was dissolved in 1856 when Hering decided to devote his whole energy to photography but he only disposed of his printing business in 1864. When he opened his studio in 1856 he advertised “portraits taken by the collodion process, in all dimensions, from the brooch size to 12 by 10 in.” as well as “Views of Sebastopol and the Crimea, by Robertson”.10The Athenaeum, Nº 1498, 12 July 1856, p. 850 Hering was a successful photographer who took and published stereoscopic images and was the London agent for the Alinari brothers, Felice Beato and Bisson Frères. He embraced the carte-de-visite craze and published dozens of portraits of celebrities of the time which he had either taken himself or bought from somebody else. There are cartes-de-visite of Florence Nightingale with his name and address on them but he was never the author of the negatives and only published them under his imprint. Hering died a wealthy man in 1893, just under ten years after causing quite a scandal in Redhill, Surrey, where he had retired around 1873. In 1884, five years after his first wife’s death and then aged seventy, he had married his 22-year-old housekeeper, Louisa Morgan.

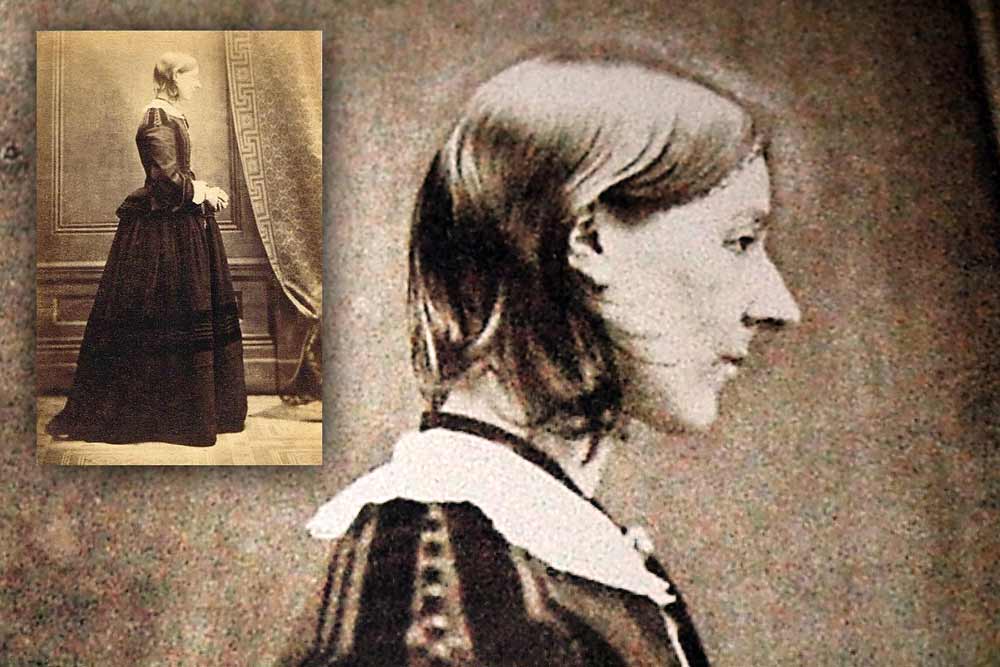

Of the three remaining names in the list of photographers to whom the photographs of Florence Nightingale are generally attributed, only two were actually behind the camera. The first one, was Claudius Erskine Goodman. He is the Goodman mentioned on page 394 by Sir Edward Cook in his 1913 two volume biography The Life of Florence Nightingale. There is no explanation, just a caption under a photograph: “Florence Nightingale – about 1858 – from a photograph by Goodman.” I would love to know how Sir Edward Cook found out C. E. Goodman was the author of this photograph as I have never come across any copy of it with his name although I have seen one with the name of Albert Edward Coe, several with Henry Hering’s name and more with no name at all. He is nevertheless right: the photograph showing Florence standing in front of a curtain and facing the camera (see illustration) is definitely by Goodman, and we can actually prove it.

It is a strange story that the one of Claudius Erskine Goodman. He was born in St Ives, Huntingdonshire, in 1822, the son of Neville Goodman, attorney at law, and his wife Anne, née Aspray. A little sister, Ellen Miéne, was born in 1825 but her birth probably caused the death of the mother as three years later, on the passing away of their father the deceased is mentioned as having been left a widower. Neville Goodman was apparently not very good at his job. A short obituary, published in the Huntingdon, Bedford & Peterborough Gazette on Saturday 31 May 1828 basically describes him as too nice and too honest to make a good lawyer:

The deceased was well and early wedded, but soon left a widower with two children ; and though destined to the law himself, yet never heartily a lawyer, being constitutionally either too sensitive and delicate, or so neutralized by meekness, placidity, and gentleness of spirit, as to be forbidden to shine in that profession. His natural taste pointed rather to smoother paths, purer pursuits, the study of divinity and duties sacerdotal, which perhaps, had life and health longer continued, might have elevated him into dignified or popular distinction.

Left orphans at an early age, Claudius and Ellen were brought up in Northamptonshire by their uncle on their mother’s side, surgeon Thomas Aspray (c. 1800-1862). In the 1841 census Erskine is listed as being his uncle’s apprentice. In 1843 C. E. Goodman, of Northampton, is reported as having won a second silver medal in Chemistry at the annual distribution of prizes and honours in the medical faculty of University College, London. Two years later, the Northampton Mercury announces that he has been admitted a member of the Royal College of Surgeons of London. By 1848 Claudius Erskine Goodman, Esquire, and his sister Ellen were living at 6, Radnor Place, Hyde Park. That same year Ellen married Frederic Bostock, a shoe manufacturer from Nottingham and followed him there. The 1851 census has Goodman still living at Radnor Place, along with three unmarried female servants and a 63-year-old Royal Marines Captain, J. G. Richardson. By then Surgeon and Accoucheur C. E. Goodman was in a partnership with an Apothecary and Accoucheur named William Henry Hodding. This partnership was dissolved on 31 March 1851, the day following the census. It is interesting to note that hroughout his life, Goodman had quite a few different business partners in as many different ventures but that these partnerships never lasted more than a couple of years.

Although there are no known photos of Goodman, there is, in some unlocated part of the world, a miniature portrait of him, painted by John Watson and exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1852. Maybe it will turn up one day and we shall know at last what this gentleman looked like.

In 1853, Goodman’s name appears as one of three partners dissolving their partnership as nursery seedmen and florists! The other two partners were his brother-in-law Frederick Bostock and one Philadelphus Jeyes. That same year, on 7 April, Goodman was elected a member of the newly born Photographic Society. Elected on the same day – it may have some importance – was Liberal Party MP for Winchester John Bonham Carter (1817-1884), Hilary’s brother and Florence Nightingale’s cousin.

In 1854 John Watson and C. E. Goodman were sharing the same premises at 2, Westbourne Grove, Bayswater. Goodman was still a surgeon and was now in partnership with one of his Aspray cousins. The 1854 British Medical Directory for England, Wales, and Scotland lists Goodman as being a surgeon at the Paddington Provident Dispensary.

On 6 August 1856, The Times published the following advertisement:

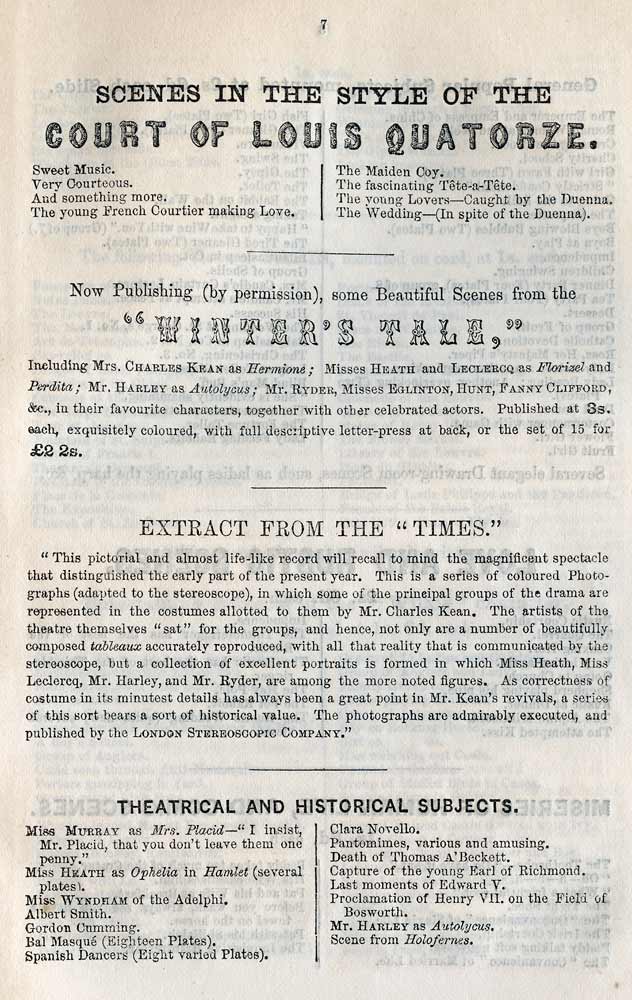

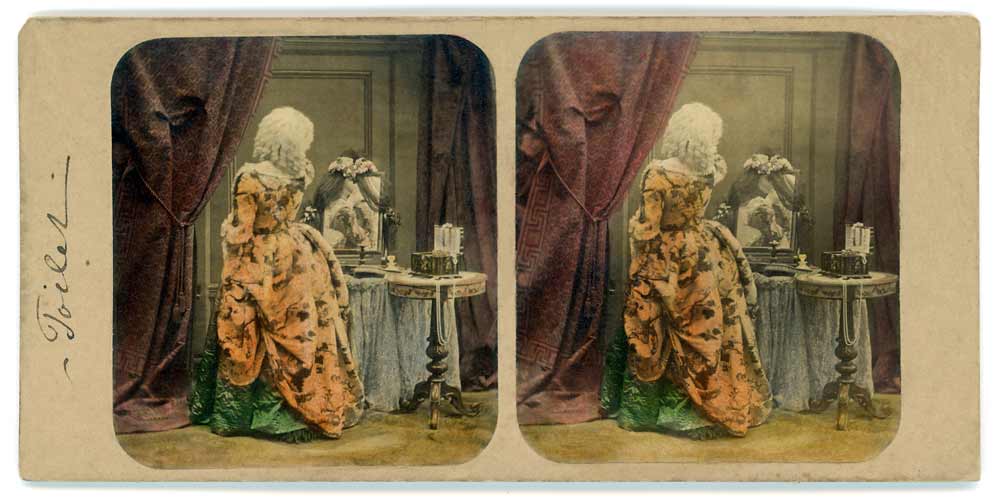

[Advertisement.] — On the 10th inst. a Series of Stereoscopic Scenes from the “Winter’s Tale” (so exquisitely placed upon the stage by Mr. and Mrs. Kean) will be published by the London Stereoscopic Company, 54, Cheapside, and 313, Oxford-street. The scenes will comprehend the principal actors in this gorgeous “spectacle,” and each subject will be explained by descriptive letterpress, with quotations, and will form the most classic and beautiful series of binocular pictures ever issued. Orders can only be executed in the sequences in which they are received. Suitable Stereoscopes, 10s. 6d. to 21s. each. The set will consist of 15 subjects and be exquisitely and beautifully coloured. £2 2s. the set, or 3s. each singly.

The date of publication was changed to the 12th five days later but on 16 and 21 August, a new ad appeared in The Times:

WINTER’s TALE in the stereoscope, exquisitely coloured, 3s. each, or 42s. the set of 15. — LONDON STEREOSCOPIC COMPANY, 313, Oxford-street, and 54, Cheapside. These form the most beautiful series of binocular pictures ever issued, and every one possessing a stereoscope must possess them. “Their groups and views are the finest we ever saw.” — Art Journal. Stereoscopes from 3s. each ; and slides from 9d. each.

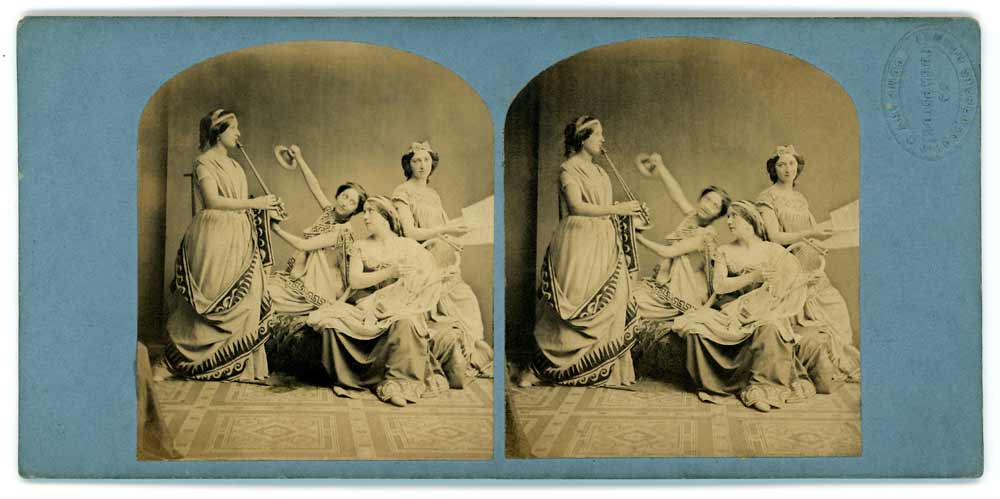

Why are these ads relevant ? Because the unnamed photographer responsible for this set of 15 stereoscopic slides was none other than Claudius Erskine Goodman. The London Stereoscopic Company – dear to our heart – had been founded two years earlier by George Swan Nottage (1823-1885) and his cousin Howard John Kennard (1829-1896). What started as an art repository specialising in bronze statuettes soon became the main dealer and maker of stereoscopes and stereoscopic slides in the United Kingdom. By May 1856 the London Stereoscopic Company had issued their first catalogue which was followed in October by a second one inserted at the end of Sir David Brewster’s The Stereoscope, its History, Theory and Construction and by a third, augmented one, in December. The latter contained a reference to the Winter’s Tale slides along with an extract of a review from The Times. Other “Theatrical and Historical” stereoscopic slides were listed on the same page, most of whom by James Elliott but with one portrait (several actually) of actress Miss Julia Murray as Mrs. Placid (from Inchbald’s Everyone has his Fault) by Goodman. Claudius must have been an admirer of Miss Murray as he not only took stereo photos of her but exhibited a portrait of her in the same role at the Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition.

The publication of the Winter’s Tale slides as early as August 1856 is important because, if you remember, this is the time when Florence Nightingale came back from the Crimea and got home after nearly two years’ absence. We saw that she was not back in London until November 1856 and that by September 1857 she was ill in Malvern. There are good reasons to believe Goodman took his photo (photos actually, since there are two) of Florence between November 1856 and the Spring of 1857 and not in 1858 as is often indicated beneath those two images. Why so ?

First of all the second photo taken by Goodman and not so iconic as the first one, shows Florence Nightingale in profile without a bonnet on. The photo reveals she had quite short hair then. We know she had short hair when she got back to England as Queen Victoria herself mentions the fact in her Journals on Monday 22 September 1856:

Miss Nightingale came, dressed in black with a simple little cap, tied under her chin, her hair having been cut off (actually on account of the insects with which the poor men were covered in the Hospitals!).

The day before she had described her in the following way :

She is tall, & slight, with fine dark eyes, & must have been very pretty, but now she looks very thin & care worn.

Secondly it is my theory that Jerry Barret, who, according to Newman, had promised to “carry on the attack in England through some influential quarters” actually did so, and somehow convinced Miss Nightingale if not to sit for him for hours at least to sit for a photographer for a few minutes. The other explanation would be that Florence Nightingale, after her return to England, regretted her repeated refusals and, relenting, accepted to have her photo taken to help Barret finish his work. That would also explain why she had her profile taken and was photographed without her bonnet on as it would certainly have proved helpful to a painter to have pictures of her head from different angles and to be able to see her full head of hair. Barrett himself drew a frontal sketch of Florence and two profile ones while in Scutari. What is striking is that if you look at the preparatory oil sketch Barrett showed Florence in July 1856 and then at the finished picture you will notice that in the former she is wearing a cap and hood very similar to the ones hastily sketched by Barret in June, when he first sighted her, but that in the completed composition she is dressed exactly – skirt excluded – as she is in Goodman’s photograph. It makes little doubt that Barret used Goodman’s images to get the likeness everyone admired so much. Since the painting was finished by the end of June 1857, it follows the photographs must have been taken prior to that date and not long after Florence’s return to London in November 1856.

There are in Dr. Brian May’s collection (now the London Stereoscopic Archive) a couple of stereocards that show beyond doubt that Goodman is the author of the photographs, even though his name is never mentioned anywhere – apart from Sir Edward Cook’s book – in relation with those images. If you look at the first illustration below – Contemplation – you can see the model is standing in front of the same curtain as Florence is. In the second one, captioned Toilet on the front, the same curtain and background that are to be found in the portrait of Florence can cleary be made out. The other three images, all borrowed from the set of 15 scenes from Charles Kean’s 1856 production of Shakespeare’s Winter’s Tale, show the very same carpet Florence Nightingale is standing on. Its pattern is very easily recognisable and I have never seen it anywhere else.

Goodman’s photos were taken, originally, either for Florence herself or for Barret. They were “artistic studies” in a way. How they came to be eventually comercialised remains, alas, a mystery as is the date when they started to be sold as cartes-de-visite. Florence Nightingale most probably had copies of them at a very early stage. There is a pencil portrait of her by Sir George Scharf (1820-1895) which bears the mention “Miss Florence Nightingale at Embley. December 28th 1857.” For a while this was thought to have been taken from life but it is obvious, when one looks at it carefully, that it has been copied from one of Goodman’s portraits. We know that Scharf spent a few days with the Nightingales at Embley but Florence was not there for Christmas 1857 and there is no reason why she would have sat for Scharf when she refused to do so for everybody else. The date of the drawing however shows that by December 1857 the photographic portrait – which Florence apparently didn’t like, saying that it made her look like Medea after killing her children – had been given to her family who did not mind showing it to visitors. It also further corroborates my theory that it was made early in 1857.

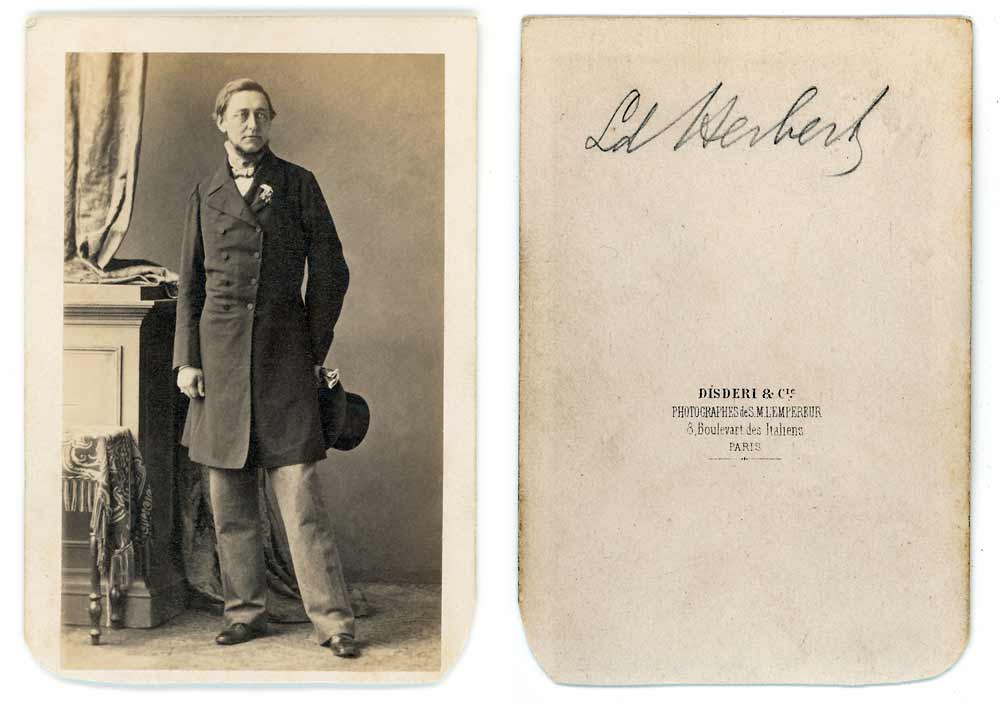

Goodman’s portraits of Miss Nightingale, though they are mostly found as small format prints, were not made with a stereoscopic camera. Goodman was taking lots of stereo images at the time but although I tried with every copy of Florence’s portrait I could lay hands on I could never find a stereoscopic pair. It may seem a bit strange since a stereoscopic portrait would most certainly have helped Barrett achieve a good likeness of her face and would have more adequately replaced a proper sitting. The small format of the binocular image, however, would have made it more difficult to get a good view of her features. The Goodman pictures were not made with a carte-de-visite camera either. Cartes-de-visite, although patented in 1854 by André Adolphe Disdéri11 Patent Number 21502 taken out by André Adolphe Disdéri, photographer, 3, Boulevard des Italiens, Paris, on 27 November 1854, took some time to become popular and were not introduced in Britain until May 1858. They were then called Photographic Visiting Cards (the exact translation of the expression cartes-de-visite, thus called because they are the same format – about 61×100 mm – as visiting cards of the time) and are first mentioned in an advertisement that was published in The Times on 27 May 1858:

PHOTOGRAPHIC VISITING CARDS. — Messrs. A. MARION and Co. have the pleasure of inviting the attention of the nobility, gentry, and the public to an entirely new mode of preparing VISITING CARDS, which, from their perfect novelty and peculiar interest, cannot fail to secure patronage as soon as known. Instead of the name being printed, a photographic likeness will be mounted on ivory cards, and thus enable every one at the slightest cost to retain a special album in which these faithful portraits of their family and friends can be preserved. By this method unusual facilities will also be afforded for the transmission of perfect photographis through the post. The cost of the plate being once defrayed, these cards will not much exceed in price the ordinary ones. The best guarantee that Messrs. A. Marion and Co. can offer for the fidelity and artistic finish of the portraits will be found in the fact that they have secured the aid of Mr. Herbert Watkins, the well-known photographer of Regent-street, who will render his valuable services to fully develop this most novel application of the art. Price one guinea and a half for 100 ; two guineas for 200 ; and half a guinea for each succeeding 100, to be had at any time. Papeterie Marion, 152, Regent-street, London.

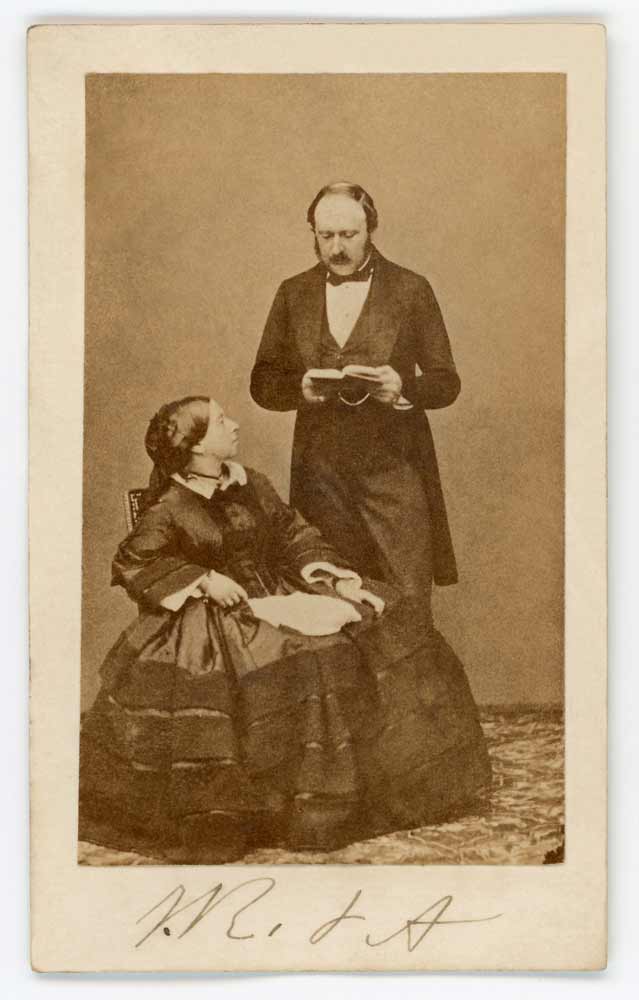

Cartes-de-visite became popular in France in 1859 after Emperor Napoleon III, who was about to leave for Italy to fight the Austrians, made an appointment with Disdéri on the eve of his departure and had his, his wife’s and his son’s portraits taken. The images were soon displayed in every shop window in France enabling the Emperor to be still present in everybody’s mind although he was physically absent from the country. A very clever move ! In Britian the craze for cartes-de-visite started in the second half of 1860 when Queen Victoria allowed photographer John Jabez Edwin Mayall to sell reproductions of portraits of herself, her husband and their nine children, in that format. The photos had been taken on 15 May and 1 July 1860 and were released in August under the generic name of Royal Album. It was thus described in The Times:

THE ROYAL ALBUM.—Under this title Mr J. E. Mayall, the photographer, has just published a series of portraits of the Royal family of England. The illustrious personages are shown without those stately appurtenances which are usually copied in portraits, and are represented as the members of a private circle, engaged in domestic pursuits alone.; Her Majesty reads a book, and the Prince Consort looks over her; the Prince Consort, in his turn, is represented; reading, and apparently referring to the opinion of her Majesty ; then her Majesty nurses the Princess Beatrice, then she stands alone, without visible occupation, as also does: the Prince Consort. The Prince of Wales and the Princess Alice next appear together as an affectionate brother and sister, and are afterwards seen separately, each in a state of contemplation, the thoughts of the Princess being apparently of a more serious character than those of the Prince. Prince Alfred next comes alone, and is followed by the Princesses Helena and Louise, who first seem consulting each other on the subject of their studies, then appear each as the occupant of a separate engraving. The young Princes Arthur and Leopold wear the Highland costume, and are first grouped together as types of juvenile affection, after which the elder of the two, still in the Caledonian habit, appears alone. The procession is closed by the little Princess Beatrice, in the full glory of a ball-dress. All these portraits are exquisitely finished, and are especially interesting from the circumstance that they exhibit the inner life of Royalty. Such a collection could not, of course, be published without the consent of her Majesty ; and, as this is granted, her own approval of Mr Mayall’s work is almost officially proclaimed. There are two forms of publication. Proof impressions on India paper are contained in a portfolio, while the subsequent impressions are in a small volume, bound with elaborate elegance and fitted with gilt clasps. To show the curiosity which has been shown on the subject of the portraits it maybe mentioned that the wholesale publishers have already demanded no less than 60,000 sets. – The Times.

What follows is history. With the precedent of the Royal Family having their intimacy thus made public everybody wanted to have their cartes-de-visite taken and soon tens of thousands of these images were produced that would be pasted in albums and shown to visitors and friends. Family albums often contained photos of the Royal family but also of celebrities of the time. Florence Nightingale, although she kept to herself and shunned public attention – something millions of attention-seekers on Instagram, Facebook and Twitter must find very difficult to understand – was definitely a celebrity worth adding to one’s album.

I would really like to know the current location of the original negatives by Goodman, if they have survived that is. Since close ups were made from them – some simple enlargements of her face, as in a CDV kept in the collection of the national portrait galleries, others heavily retouched copies – we can deduce they were quite large and were subsequently reduced to carte-de-visite format. If anyone has any clue as to the whereabouts of those negatives, please contact me.

Another very important question remains unanswered. Why Goodman ? There were lots of photographers, far more renowned than he was, who could have made Florence’s photographic portrait: Claudet, Kilburn, Mayall, T. R. Williams, to name but a few. So why choose a rather obscure practitioner ? Was it exactly because he was fairly obscure and never put himself forward ? It is true that his studio, at 118 New Bond Street, was very close to Florence’s residence in Old Burlington street. But so was Kilburn’s, Mayall’s or T.R. Williams’s. Did Florence’s choice have anything to do with the fact that he was also a medical man and was her cousin John Bonham Carter instrumental in arranging a sitting ? I am afraid we will never know for sure. Jerry Barret never mentioned he had used photographs to finish his painting. Few artists ever acknowledged that fact even when we have definite proof that they did. As for Goodman, he was always silent on the subject and did not even insist on his name being mentioned on the cartes-de-visite that were later published from his negatives by Henry Hering and others. After all it had not been mentioned either when the London Stereoscopic Company published his scenes from the Winter’s Tale.

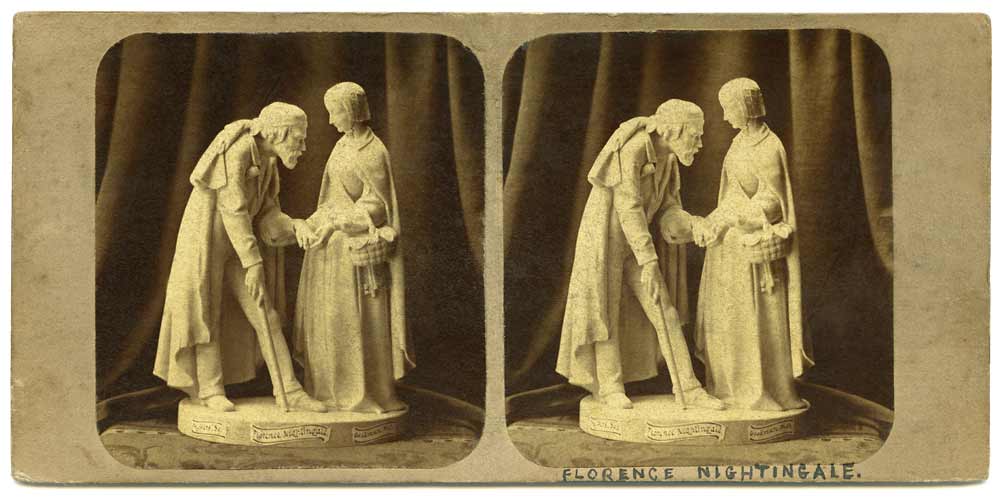

It may be of interest to the readers of this article that Goodman was involved in the making of a couple of other photos, stereo cards this time, showing Florence Nightingale. They are, unfortunately, not real portraits but the stereoscopic images of a statuette made by Belgian-born artist Theodore Jean Baptiste Phyffers (c. 1820-1876). This work, entitled The Wounded at Scutari and showing Florence talking to a wounded soldier, was commissioned by Florence’s friend Selina Bracebridge in aid of a fund to support her work and was sold from 1858 onwards after being first exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1857. It was described in the February 1858 issue of the Art Journal and was accompanied by a nice engraving of it:

The work we have engraved was executed for Mrs. Bracebridge, the intimate friend of Miss Nightingale, and for a considerable time her companion and fellow-worker in the Crimea. Miss Nightingale could not be prevailed upon to sit to the sculptor, — she has no desire to be immortalised by the hand of any artist, — but he had several opportunities of seeing the lady, and marking the outlines and expression of her features: the likeness is satisfactory to those who know her well. He has treated the figure in a conventional but very picturesque manner, and in the act of addressing a veteran soldier apparently just risen from his bed of suflering: it is a touching subject, that cannot fail to excite feelings of sympathy and admiration in all who look at it. The original work was exhibited at the Royal Academy last year.

This time, Goodman signed his work by adding a label with his name and the mention “phot.” on the base of the group. There are a couple of variants of this photograph.

The rest of Goodman’s life can be summed up in a few lines. He went ont taking photographs for a while, exhibited portraits at the Photographic Society and at the Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition, finally married in 1859, and became quite famous with his stereos of staged scenes, of North Wales and of statuary as is confirmed in this advertisement published in The Athenæum on 7 April 1860:

STEREOSCOPIC. GOODMAN’S GROUPS, STATUARY, &c. – A. W. BENNETT having undertaken the Wholesale Agency for this well-known Artist, has now on hand, in addition to those already known to the public, A NEW SERIES, combining appropriate Figure Groups, with romantic and celebrated Natural Scenery. Coloured 1s. 6d., post free. Prepaid Slides exchanged if not approved. Or parcels for selection on receipt of reference.

Wholesale Dépôt – 5 Bishopsgate-street Without, London E.C.

After John Watson, who became blind in 1862 and died in 1865, Goodman had other business-partners for short periods, patented an invention for the “improvement in machinery employed in the manufacture of boots and shoes”, and carried on medicine almost to his dying days as he is listed as a general practitioner in the 1871 census. He passed away at 10 Shrewsbury Square, St. Stephen’s Square, Westbourne Park, on 12 February 1873. He was only 51 years old.

The other iconic images of Florence, one showing her seated, looking down, and the other one standing next to an ornate plinth, looking to her right, are the work of a single photographic artist, the well-known Regent-street portraitist William Edward Kilburn (1818-1891). They were taken in two different sittings and there exist a variant of the seated one [12] and at least two of the one where she is standing. The latter were often published as vignettes, showing only the face and shoulders of the famous model. These images, like Goodman’s, were not photographed for the stereoscope or with a carte-de-visite camera as is evidenced by the enlargements that were made of them, which would not have been possible had the original photographs been taken on small negatives.

Let’s start with the two images showing her seated. There is some debate about when these pictures were taken. It is thought by some that they were made at the time Florence Nightingale was running the Upper Harley Street establishment, that is BEFORE her departure for the Crimea. Others believe the images were made in the late 1850s-early 1860s, AFTER her return to Britain. I personally think that all of the iconic Nightingale images (Goodman’s and Kilburn’s) were taken between November 1856 and 1860. In all of her portraits, including the Goodman ones of 1856-57, she is wearing the same neckwear, a velvet ribbon held in place around the neck by a brooch or pin (always the same) to which is tied a flat chain ending in something (pince nez, watch or other) which is never visible. What are the chances of her wearing that neckwear and brooch/pin in 1854, go to the Crimea for nearly two years where she had no use of such fairly simple but still fancy adornment, and put on that very same neckwear for her later portraits made over two different sittings ? Pretty slim, I would say.

Since we are examining what Florence is wearing it is not useless to note that in all of the Kilburn photos, although one can clearly see two different dresses, Florence is wearing the same white cap and the same collar, which are different from the ones she has on in the Goodman portraits. This could be considered evidence that the Kilburn portraits were made around the same time.

The only thing we know for sure about the Kilburn photographs, as far as the date of their making is concerned, is that they were taken before 1861 for the seated ones and before 1863 for the standing ones.

A copy of the photo where Florence is seated with her head down is in the Royal Collection, in an album collated by Prince Albert himself in 1860-1861 from photographs he bought. Since the Prince died in December 1861 the photo must have been acquired before that date. The Florence Nightingale Museum have in their collection a testimonial presented to a Henrietta Walker celebrating the first year since the introduction of trained nurses at the Liverpool Workhouse. It is framed and includes a signed photograph of Florence Nightingale – one of her vignetted head – dated 18 July 1861. Finally, 1861 is also the year when the first advertisement mentioning a carte-de-visite of Florence Nightingale appears in the press. The ad, published in Saunders’s News-Letter on Friday 15 March 1861, is all about the goods sold by photographer James Robinson, of 65, Grafton-street, Dublin.

PHOTOGRAPHIC ALBUMS, CARTES DE VISITE. – JAMES ROBINSON begs to announce that he has now on sale a magnificent Collection of Photographic Albums of every size and description, including the Albums à Coulisse, made expressly for the Cartes de Visite Portraits; also an immense variety of Album Portraits of Eminent and Popular Personages, including her Majesty the Queen, his Excellency the Earl of Carlisle, Lord Gough, his Grace the Archbishop of Dublin, the Duke of Cambridge, Miss Florence Nightingale, &c., &c. – Polytechnic Museum and Photographic Galleries, 65 GRAFTON-STREET.

A few months later, on 24 August, it was the turn of the Reading Mercury to publish an advertisement mentioning a carte-de-visite of Miss Nightingale, sold this time by a Newbury photographer:

CARTES DE VISITE.

PORTRAITS of EMINENT PERSONS. The Royal Family, the Bishops of Oxford, London, Exeter, Lincoln, Winchester, St. Andrews, &c., Lords Derby, Palmerston, Herbert, Brougham, Macaulay, &c., Archdeacons Rundall, Clerke, Bickersteth, Denison, &c., Revs. T. Carter, W. Gresley. Bryan King. C. Kingsley, Count Cavour, Miss Nightingale, and very many others.

A large assortment of Albums for the above, 10s. 6d., 16s., and 30s. each. Selections sent out for approval. – Sold by E. Lack, Bridge House, Newbury.

Although the photograph is not described in either ad, I have reasons to believe it is the seated portrait of Nightingale by Kilburn since an engraving made after the very same photograph was published in the German weekly illustrated magazine Über Land und See soon afterwards, on 3 March 1862. It is, to my knowledge, the first likeness of Florence Nightingale after a photograph ever published in the press and I find it very surprising that the Illustrated London News, in which dozens of engravings after Kilburn appeared over the years, never published this or any of his other portraits of Florence until 1907! But more of that later.

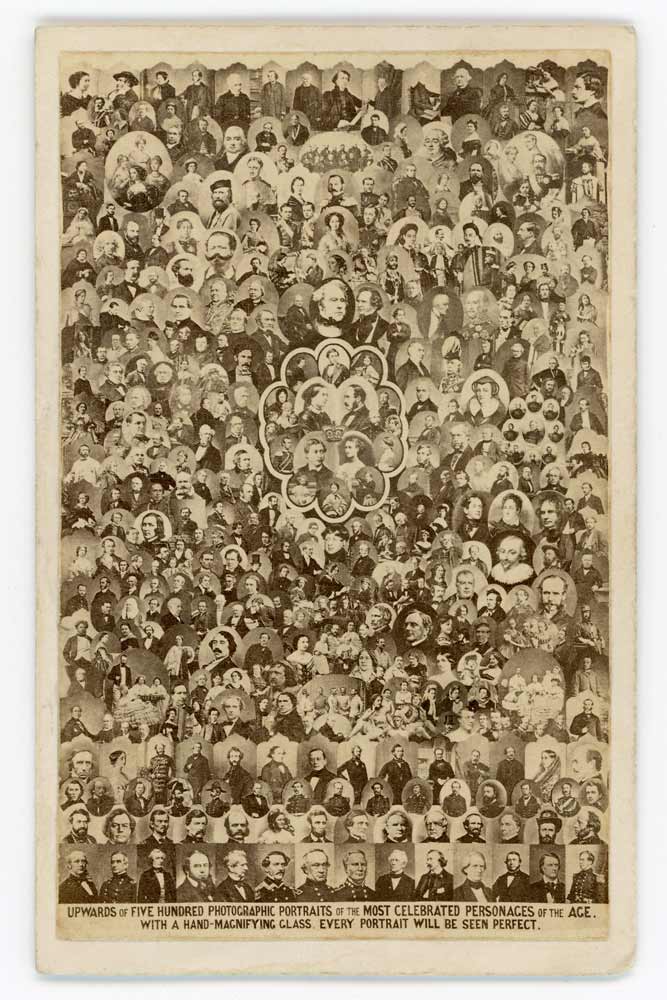

As for the photo of Florence standing next to a plinth, it appears in a mosaic carte-de-visite entitled Upwards of five hundred Photographic Portraits of the most celebrated personages of the Age, first published in 1863. The earliest advertisement for it I have found so far, dated 21 May 1863, appeared in the Limerick Chronicle on Saturday 13 June. Here is an extract from it:

A perfect novelty – A Carte de Visite – containing upwards of 500 portraits of the most celebrated personages of the age, price 7 stamps.

[…]

JOHN NORTON

22, George-street, Limerick.

May 21.

Later advertisements describing several mosaic cartes-de-visite, including the Upwards of five hundred Photographic Portraits one, appeared from November 1863 onwards in the Tavistock Gazette.

There is another question about the Kilburn images that needs to be answered. Even though most of the copies of the seated portraits of Florence bear the name of Kilburn or of his successor, Henry Lenthall, as well as the address of their studio, 222, Regent Street, how can we be sure Kilburn is the actual taker of the photographs ? After all, we saw with Goodman that he is never credited as the real author of his two Nightingale portraits and that names printed on cartes-de-visite can be misleading. The answer is simple: props.

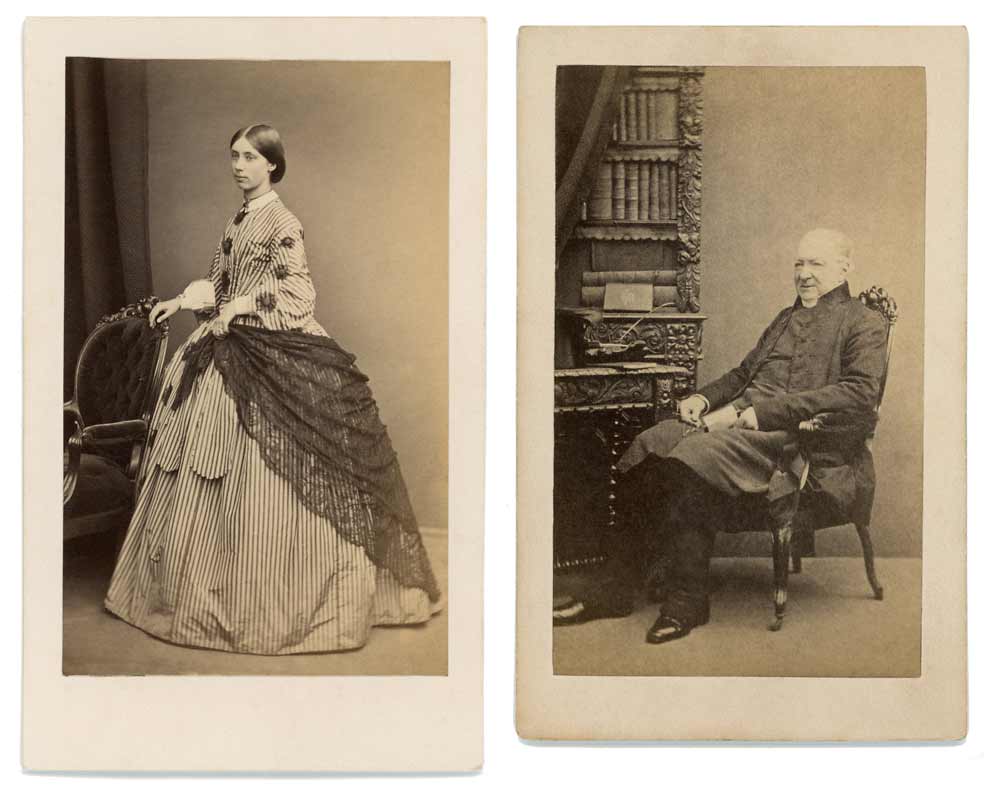

The armchair on which Florence Nightingale is sitting in the two seated portraits appears in dozens of other images by Kilburn, as does the plinth she is standing next to in the standing photographs. This plinth, by the way, is actually the base of a prop bookcase which is used a lot in Kilburn’s photographs and can be easily spotted in some of his early daguerreotypes as well as in his later cartes-de-visite.

I have not dwelt too much so far on the life and work of William Edward Kilburn or of his successor Henry Lenthall, and I will not do so now, as they will soon be discussed at length in an article written by my talented assistant Rebecca Sharpe. Let us just state the basic facts, namely that Kilburn was born in 1818 into an artistic family but that he preferred photography to drawing and painting. Like the goddess Athena is said to have been born fully armed from Zeus’s forehead, Kilburn appeared on the photographic scene quite suddenly and opened his very first studio in the much coveted Regent-street. Most of his colleagues and competitors, Claudet, Mayall, T. R. Williams, and Clarkington, to name but a few, learned their trade in humble studios before moving to larger premises in posh Regent-Street and they spent years getting influential patronage. Not so Kilburn ! Barely months after his studio opened – either late in 1846 or at the very beginning of 1847, it is not very clear – Kilburn was invited to the Palace to take portraits of the Royal Family which, added to the fact that he was an artist at heart and a good photographer, made his reputation almost immediately. Kilburn’s first studio was at 234, Regent-street, but in July 1855, he moved further down the street, on the same side, to number 222, south-corner of Argyll-place. This is important because I have never seen any prints of Florence Nightingale’s portraits bearing the 234 Regent-street address which would seem to corroborate the fact that her photos were taken after her return to her mother country in 1856.

Again, as with Goodman, we have to ask ourselves why Florence Nightingale chose Kilburn to be photographed. Despite the lack of any evidence in the Royal Collection and in the correspondence between Queen Victoria and Miss Nightingale contradicting or corroborating the latter’s statement, was Florence actually commanded to have her portrait taken and if so did Queen Victoria herself recommend Kilburn as a competent and discreet photographer ? Could anybody else have recommended him ? There is Swedish singer Jenny Lind, for instance, whom Kilburn took a couple of portraits of in 1848 and who, assisted by her husband Otto Goldschmidt, organised a concert to raise money for the Nightingale fund in March 1856. She could have told Florence about Kilburn. There could be lots of other people too, either friends or family. One more time, I am afraid we may never know for sure.

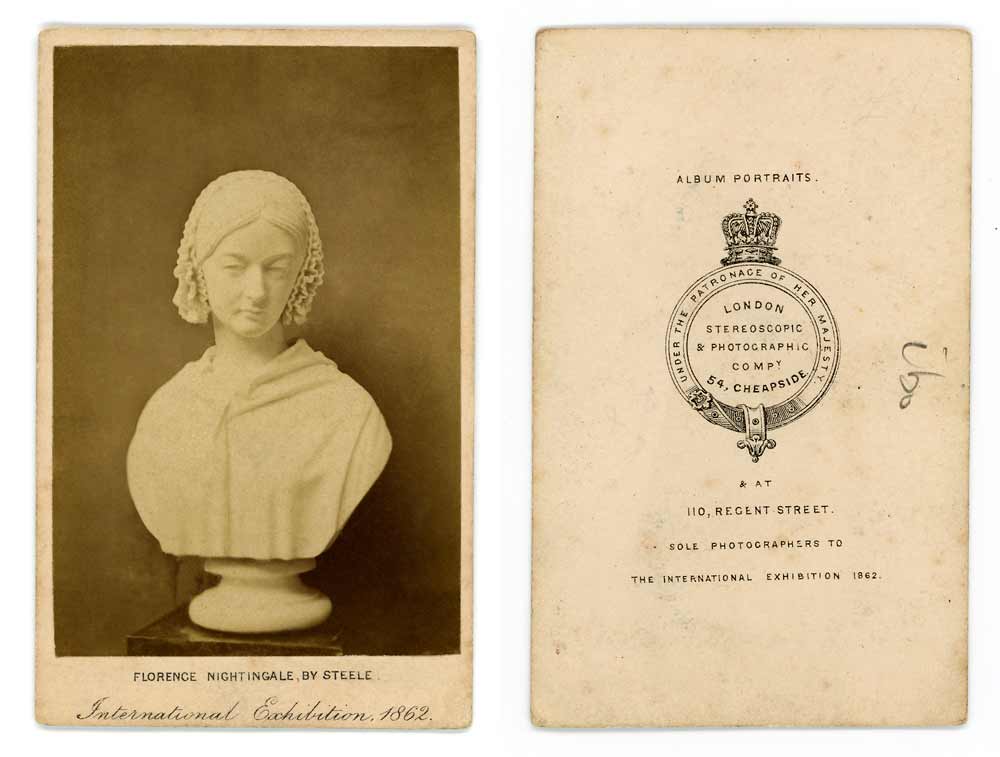

If you have been attentive to what precedes you may have noticed that although the London Stereoscopic Company was mentioned earlier as being responsible for some of Florence Nightingale’s iconic photographs their name has only been used so far in reference to the publication of Goodman’s stereos of Charles Kean’s production of The Winter’s Tale, in 1856. Why then is the name of the London Stereoscopic Company linked with that of the founder of modern nursing ? Well, it is a rather complicated story. Before the 1862 Exhibition opened its doors in London, the London Stereoscopic Company had bought for a considerable sum the privilege of being the only authorised entity to take and sell photos of the inside of the Exhibition Palace and of its exhibits. They produced hundreds of stereoscopic cards and cartes de visite of the exhibition. Among the works of art on display there was a bust of Florence Nightingale by Sir John Robert Steell which had been commissioned by the Crimean soldiers with a penny subscription. Nightingale happened to like Steell’s work in general and when it was suggested could not refuse the homage of the bust as it was paid for by the very soldiers she had looked after. However, due to chronic illness she could only sit for the artist twice, and even so, for a short period each time as it tired her a lot. The bust, therefore, was not completed until 1859 and for a couple of years was much admired in the artist’s studio where it reached the status of “relic”, something that Florence Nightingale had dreaded from the start. In 1862 it was finally offered to Florence who, although she came to hate the thing and wished it smashed, could not but accept the gift. The bust was displayed during the 1862 Exhibition and was photographed by the London Company. On 2 December 1852, George Swan Nottage and Howard John Kennard, copyrighted the photograph of Steell’s work which you can see below. It is worth noting that this is the earliest copyright of a photograph connected to Florence Nightingale, neither Goodman nor Kilburn having copyrighted any of her portraits. It was not until 10 July 1866 that Henry Lenthall (1820-1897), who had worked for Kilburn from at least 1859 and had succeeded him in 1862, copyrighted an actual portrait of Nightingale, or, to be more specific, a vignette of her head and bust, made from a negative taken by Kilburn some years earlier.

The connections between Florence Nightingale and the London Stereoscopic Company do not limit themselves to the photo of Steell’s bust. In 1897, nearly forty years after they were taken (!) the London Stereoscopic Company copyrighted on two separate occasions three of Kilburn’s photos of Florence. The first ones to be registered, on 12 April 1897, were the full length portrait of Florence standing next to the base of the Kilburn bookcase, and a partial enlargement of the same photo. The former was described in the copyright slip as a “Photograph of Florence Nightingale, three quarter face, full-length figure, body turned to her right”, and the second one as “Photograph of Florence Nightingale, three quarter face, body turned to her right.” A copy of the images was annexed to the descriptions. The proprietor of the copyright was the London Stereoscopic and Photographic Company and Henry Lenthall was listed as the author of the works. By 1891 Kilburn had been dead for over six years and on selling his studio to Lenthall in the mid 1860s he had relinquished his rights to his negatives so that Lenthall could actually claim he was the author of the images. Lenthall himself was at death’s door in April 1897 and by the time the London Stereoscopic Company went back to Stationer’s Hall to register the two seated photos of Florence, on 27 April, he was dead and buried. The two images were respectively described as “Photograph of Florence Nightingale full length seated, full face” and “Photograph of Florence Nightingale full length seated”. And that’s how the name of the London Stereoscopic Company came to be associated with the photos of Miss Nightingale ! If you remember, Elizabeth Robinson Scovil had bought a photo of her idol from their premises on 29 March 1897, which means the LSC were selling photos of Florence even before they officially owned the copyright.

Goodman’s and Kilburn’s portraits had an abnormal longevity. Since Florence refused to have her photograph taken for decades the photographic images the two Victorian artists had somehow managed to snatch were the only ones to be had until nearly her death in 1910. In 1872 the American artist Timothy Cole (1852-1931) engraved the portrait made by Goodman while the standing Kilburn one was published by Cassell & Co. in April 1887 in part XI of a publication entitled The Life and Times of Queen Victoria. The portrait was not attributed.

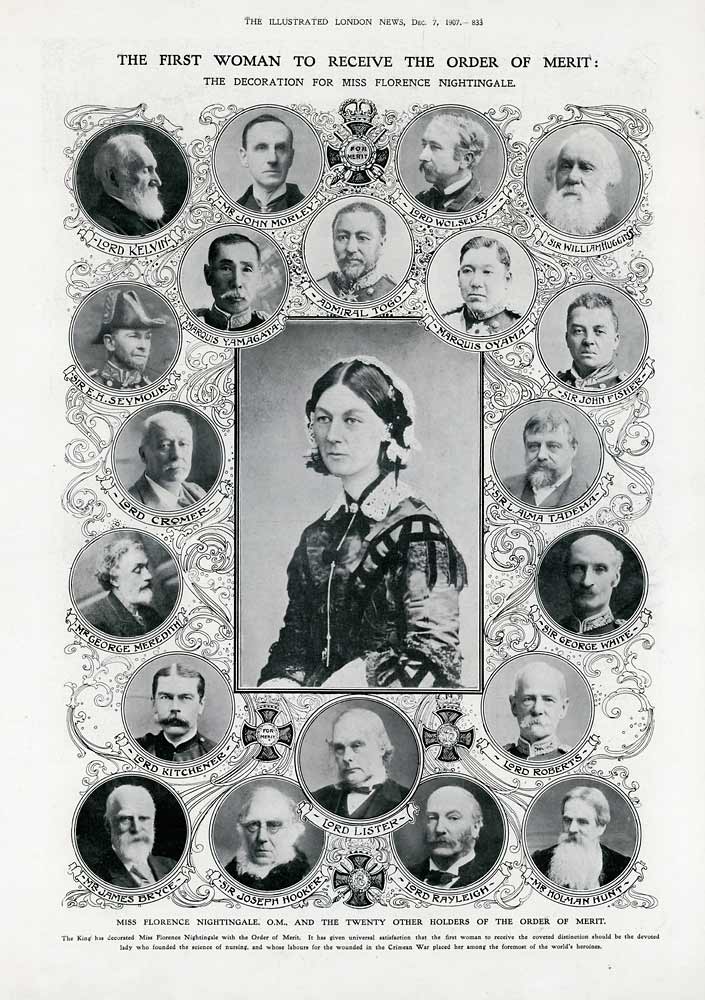

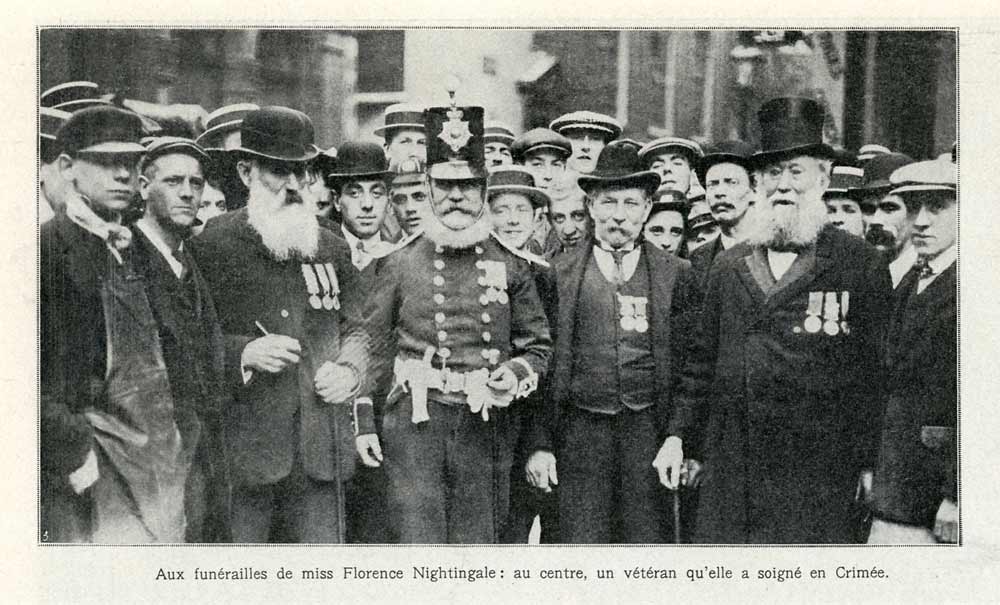

When in 1907 Florence Nightingale became the first woman to receive the Order of the Merit, the Illustrated London News published a portrait of all 21 holders of this prestigious award. The photograph they used for her was the one by Kilburn where she is standing next to the base of the bookcase. It was used again three years later, to illustrate articles about her death and/or her funeral not only in Britain but also in France and in Germany. One can easily understand why this image, as well as Goodman’s frontal portrait, immediately spring to mind when the name Nightingale is mentioned.

One last remark to conclude. All through her life Florence maintained that she had sat for her photographic portrait on a single occasion and by royal command only. I have shown this is an untruth and explained why she stuck to her version of the facts in order to be left alone. She even denied any knowledge of photos of her although we have seen there are copies signed by her is some private and public collections. Ironically one of her very last portraits from life – not a photograph, unfortunately, but a chalk drawing – was actually made by royal command. In 1908, King Edward VII expressed the wish of having portraits of all the recipients of the Order of the Merit. We saw that when Florence was awarded the Order of Merit in 1907 the ILN published a late 1850s photo by Kilburn because that was probably the only portrait of her they had. The task of obtaining the likeness of Miss Nightingale fell to sculptor Countess Feodora Gleichen (1861-1922) who visited the invalid and sketched her sitting up in what was her office for over a decade, her bed. Florence’s lie had become true at last: she had sat for her portrait once, by royal command !

There are still many unanswered questions about Florence Nightingale and her photographs. The legendary model could obviously have provided all the answers but, to my knowledge, she never divulged them and took her secrets to her grave. I can only hope that this article has provided some new information as well as some food for thought. I have written it not only to share what I have found out about those images but also because I would like it to be a “message in a bottle” of sorts. With a little luck, someone who knows some of the answers may find it, read it and provide the help needed to solve one or more of the mysteries that still surround those photographic icons. Wouldn’t it be a good way to celebrate the bicentenary of Florence Nightingale’s birth ?