Until I made my first visit to Vietnam in 2013, I knew very little about the origins of photography in that country. My focus had been on East-Asian photography – China, Japan and Korea, to be specific. And although in my past studies I had noted the occasional reference to Vietnam occasioned by visits to that country by celebrated photographers such as Jules Itier, John Thomson, August Sachtler and Wilhelm Burger, I had no intention, at that time, of shifting my attention to Southeast Asia.

Vietnam’s history has been influenced by 1,000 years of occupation by the Chinese, and more recently by a century of colonisation by the French (1850s-1950s). This was immediately followed by the Vietnam War (1855-1975). Throughout this continual turbulence, the Vietnamese have maintained their own independent culture and fierce national pride. No invading or occupying power has found subjugation an easy task.

We travelled slowly down the narrow coastline from Hanoi in the north, to Saigon in the south. On the walls of a number of coffee shops and restaurants, along the way, enlarged coloured French postcards of early-1900s local scenes and portraits were often displayed – suggestive of Vietnamese people’s latent interest in the visual history of their country. Nevertheless, visits to bookshops failed to uncover any substantive works on early photography. There were, however, several recently published printed booklets of local scenes, reproduced in French postcards of the early 20th century. On my return to Europe, I discovered that there were only a couple of French books published on 19th-century photography in Vietnam.

During our vacation, we found the people, scenery, architecture, local customs and food fascinating. Vietnam has more than 50 ethnic tribes, all with their discrete customs and colourful costumes. Following my return to London, I began to collect and research the country’s photography and ended up writing a book which was published at the beginning of this year.

Earliest Photographs

As far as we can tell, the first photographs were taken in 1845 by Jules Itier, a highly-skilled amateur photographer. He was in the Far East as head of the commercial section of a trade mission to China, the East Indies and the Pacific Islands. On hearing of the imprisonment of a French missionary in Tourane (present-day Da Nang), the French were prompted to attempt a rescue and Itier, together with his daguerreotype camera, arrived on the warship Alcmène on 30 May 1845. The negotiations with the Vietnamese were tense, and it seems that Itier only had the opportunity of taking a couple of images on the 12 June, the day of departure. These were of the Non-Nay fort, and of the Alcmène in the bay. According to our knowledge of present research, the next photo-opportunity did not present itself until 1858.

Although Vietnam did not generally welcome foreign visitors and was effectively closed to the outside world, European missionaries had been coming to the country since the 16th century. Vietnamese attitudes to them ranged from guarded tolerance to outright hostility. By the mid-19th century, the country’s rulers had outlawed Christianity and forbade, on pain of death, the practising or preaching of the religion. Nevertheless, an unknown number of mainly French and Spanish priests continued to smuggle themselves into the country. By the mid-1850s, the French had their eyes on Vietnam as a possible base for extending their colonial ambitions. The execution of two Spanish Catholics in 1857 gave the French an excuse to send warships to punish the authorities.

The timing was unfortunate for the Vietnamese since the French then had a significant military presence in the Far East due to their participation in the Second Opium War in China. In alliance with the Spanish, some fifteen warships and 3,000 troops were despatched to Da Nang. After five months of fighting and unexpectedly stiff resistance from the Vietnamese, the French managed to occupy a small stretch of coastline. It was from here that a French naval officer,Paul-Emile Berranger, took photographs. The National Gallery of Australia has a collection of twenty-three Berranger-attributed albumen prints showing the occupation. The French moved on to Saigon where they consolidated their position and would end up staying for almost 100 years.

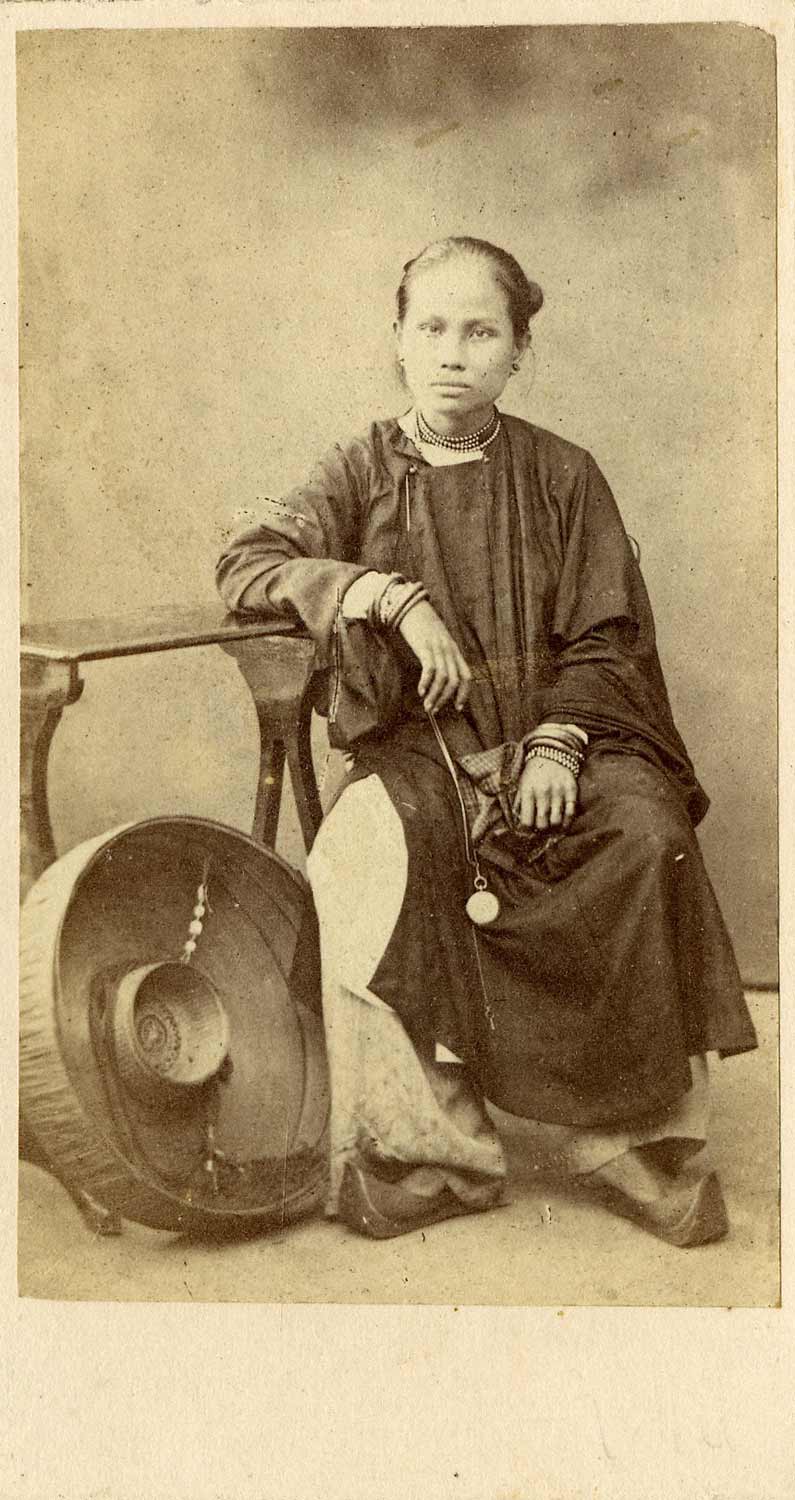

How about the earliest portraits of Vietnamese? The German traveller and amateur photographer, Fedor Jagor, appears to have taken a stereoview portrait in Singapore of three Vietnamese residents or travelling merchants in late 1857. In 1863, a Vietnamese embassy travelled to Europe in an unsuccessful attempt to renegotiate treaty terms. Some photographs of the event have survived.

Visiting French naval officers, such as Octave de Bermond de Vaulx and Jules Le Bas, photographed Saigon in 1864 and 1865 respectively. Some of these images survive in private collections, and a few appeared as engravings for periodicals such as L’Illustration and Le Monde Illustré.

Commercial Studios

The first commercial studio in Vietnam was opened on the rue Catinat, Saigon by Clément Gillet; it was first advertised in the 10 April 1864 edition of the Courrier de Saigon. Gillet was a seasoned cameraman, previously attached to the Ministry of War in Paris. Gillet’s monopoly was short-lived and broken a month later by itinerant photographer Charles Parant, also French, who had previously operated studios in Mauritius, Réunion Island and Batavia.

By 1866, both Gillet and Parant seem to have moved on. Although the number of potential customers was steadily increasing (due to the growing numbers of the French military, Colonial administrators, merchants and missionaries), it may be that commercial viability had eluded them. In 1866, the vacuum was filled by a truly talented photographer, Émile Gsell.

Émile Gsell

After spending seven years in the French army, Gsell set up his studio in Saigon sometime in 1866. We know very little about his early life, and nothing of his army career. He is famous for being hired as official photographer to the French Mekong Expedition when he took some stunning photographs of the Angkor Wat ruins in Cambodia, in June 1866. His earliest-known studio advertisement appeared that year in the 20 September edition of the Courrier de Saigon in which he offered local scenes and portraits as well as his Angkor views.

Within a year or two, Gsell had established himself as the foremost photographer in Vietnam. He died in Saigon in 1879, at the height of his fame and popularity. Surviving albums attest to the quality and artistry of his work.

Other Photographers

The Chinese studio of Pun Lun opened In May 1867. A branch of the successful Hong Kong business, it afforded the only serious competition to Gsell, before ceasing to operate in around 1872.

John Thomson visited Saigon in December 1867 and stayed three months. The purpose of his visit is unclear, but he took a series of outstanding views and portraits.

Judging by the surviving numbers of albums, the French photographers Pierre Dieulefils and Aurélien Pestel were popular. Apart from a few trips home to France, the former operated a studio in Hanoi for some thirty years (1888 -1919). At the turn of the 20th century, he turned to publishing photographic postcards and books. Pestel ran his studio for about ten years, from 1887 until he died in 1897. Raphael Moreau also seems to have been a prolific operator. His Hanoi studio appears to have opened in 1897, and continued until around 1910. Like Dieulefils, Moreau reissued a large number of his photographs as postcards.

Charles-Édouard Hocquard, the French medical officer and amateur photographer, produced an exceptional body of work during his two-year military service in the 1884-5 Sino-French War. At least 250 of his photographs are known, many of which were published in both Woodburytype and albumen formats in 1886. His work won the gold medal at the 1885 Antwerp Universal Exhibition, and in the same year, he had the distinction of becoming the first to photograph a Vietnamese emperor – Dong Khanh.

Vietnamese Photographers

According to Vietnamese sources, the first professional native photographer was Dang Huy Tru, who opened his studio in Hanoi in March 1869. A senior official at the royal court, it is said he learned photography during an official visit to Hong Kong in 1867. He is said to have photographed the 1873 arrival of the French in Hanoi. He died in 1874, and none of his photographs has so far been discovered. Truong Van San was the second commercial studio in Vietnam, opening in Hue in 1878. Again, no photographs have survived.

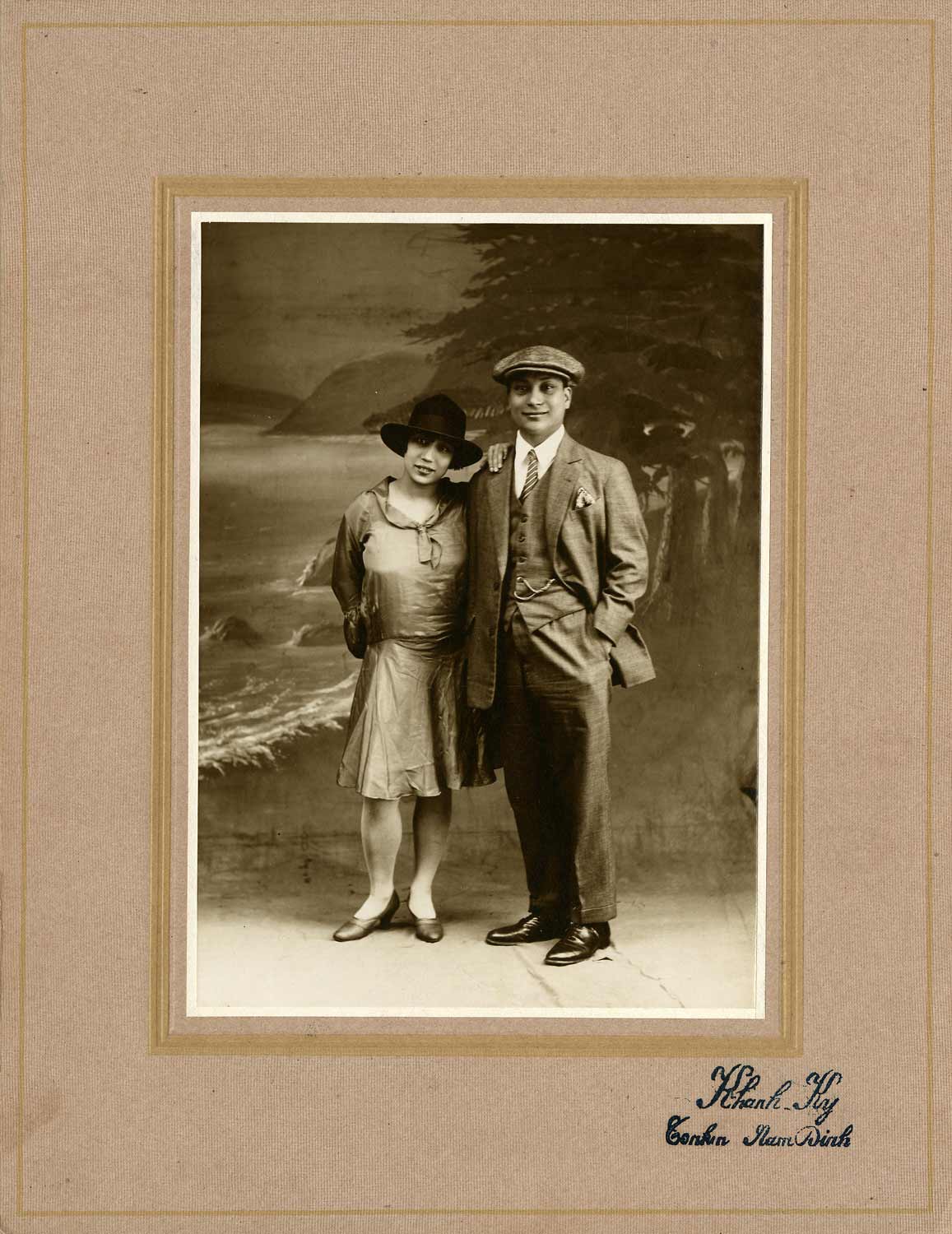

Considered the father of Vietnamese photography, Nguyen Dinh Khahn (1874–1946) opened his Hanoi studio, known as the Khahn Ky Studio, in 1892. Born in Lai Xa village, now a part of Hanoi, he learned photography at the age of sixteen at the Chinese-run Du Chuong PhotoShop in Hanoi, and two years later set up his own business. The business was hugely successful, and the Khahn Ky studio went on to operate franchises in more than 150 studios throughout the country, including thirty-five in Hanoi alone. Its tentacles reached as far as China, France, Germany and Laos. Vietnam’s only photography museum is appropriately based in Lai Xa and dedicated to the works of Nguyen. Although I have not been able to trace any 19th-century examples of the studio’s work, several from the early 20th century have survived.

A few other studios opened across the country in the late 19th century, but the first years of the next century saw a proliferation of studios, many of them run by exceptionally talented photographers.

Terry Bennett’s book Early Photography in Vietnam is published by Renaissance Books