A brief overview of the earliest photographers to have worked in the region

This article is based on a paper that was originally read at the 17th Conference of the International Association for Ladakh Studies, held in Kargil Ladakh, in July 2015

This article gives a very brief overview of the earliest photographers working in Ladakh and the surrounding areas; beginning with the very first tentative images made in the 1860’s and 1870’s, by those officers of the Indian Government Survey Department, Indian Army officers on shooting expeditions, or by members of official political missions in the region, who were also enthusiastic amateur photographers.

Ladakh, is a remote province of the North-Western Indian Himalaya, situated, to the north of Kashmir, and on the borders of Pakistan and Tibet. Although nowadays politically a part of India, it is largely culturally Buddhist and ethnically Tibetan. The province of Baltistan, which was originally a part of Ladakh, was occupied by Pakistan after the 1947 partition of India. Its peoples are ethnically similar to Ladakhis , but are now largely Muslim. The region is still a hotbed of political unrest, with ongoing border conflicts between India and both Pakistan, and China, which now occupies Tibet. Lahoul is a small Himalayan region, sandwiched between Ladakh to the north and the Kulu valley to the south.

These three regions were, during the 19th century, for a variety of reasons, geographical political, and historical, one of the most poorly photographed areas of the Himalaya. In fact during the first twenty two years, following the invention of photography in 1839, there appear to have been no photographs made anywhere in Ladakh, Baltistan, or Lahoul at all. From 1861 onwards, however, a very limited number of travellers to Ladakh, did begin to use photography, very tentatively, to document the landscape, architecture and peoples of the region. The photographs produced were very few and far between, and unfortunately the majority were not of the highest technical or artistic quality; although given the extreme technical and logistical difficulties of producing photographs in such harsh and remote terrain, using the cumbersome wet plate collodion process, it is perhaps not surprising that so few images were made during this period.

Robert, Adolf & Hermann,

von Schlagintweit

I have to start, however, by briefly mentioning the first travellers to Ladakh, who by rights, ought to have taken the very first photographs of Ladakh, but for some as yet unknown reason, didn’t!

The explorers Robert, Adolf & Hermann, von Schlagintweit, travelled through Ladakh in 1856-57, in the employ of the East India Company, en route to Kashgar.

Although Robert was an accomplished photographer, who produced fine ethnographic portraits in India and Ceylon, on this journey they made only drawings, and paintings, to document their journey; some of which were published as very fine lithographs. Why they didn’t take photographs as well is unclear; but it may well be that the sheer weight and volume of bulky fragile and complicated equipment and chemistry, needed to make photographs at that time, was deemed by them to be too difficult to carry on such a long expedition. Whatever their reasoning, it was a badly missed opportunity!

Captain Robert Melville Clarke

The first photographer known to have worked in Ladakh was a British army officer, Captain Robert Melville Clarke, who visited the region in the summer of 1861, when he took part in a 2 month long shooting expedition to Ladakh; led by the Deputy Commissioner of Simla, Lord William Hay, travelling in company with Colonel Torrens (23rd Royal Welsh Fusiliers), Major the Hon. T. de V. Fiennes, Lt. Buckley, and Ensign the Hon. T. Scott.

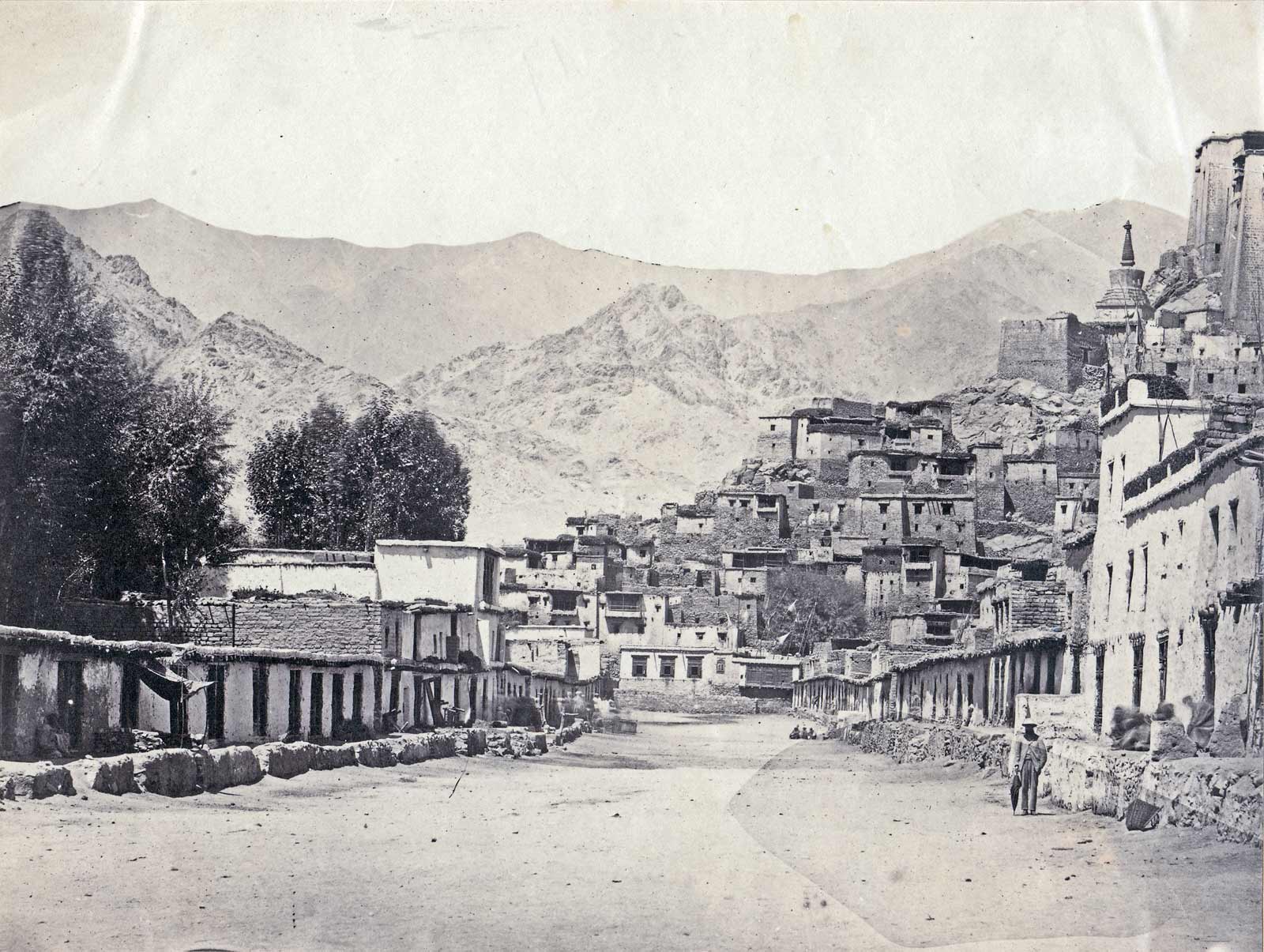

The expedition left Simla in July 1861 and travelled, via Narkanda, up through the Kulu Valley into Zanskar and Ladakh, and on to Leh. From there, they continued westward to Srinagar, the capital of Kashmir, where on September 15th, he parted company with the other expedition members and continued his travels in company with some other army colleagues that he had met with there. A keen amateur photographer, Clarke produced a number of topographical views of the region, in varying sizes, up to 10 x 12 inches. The majority of his photographs from this expedition are not especially well composed, and some are of indifferent technical quality, however, they do seem to constitute the first body of photographs ever taken in Ladakh, and possibly also in Kashmir. Some of them were later exhibited by him at the 1862 Exhibition of the Bengal Photographic Society; where they were much praised.

Clarke also went on to produce his own book of Ladakh & Kashmir views from this expedition: ‘From Simla Through Ladac and Cashmere’, which was published in Calcutta, in 1862. It contained 36 mounted albumen print views of Simla, Kulu, Ladakh & Kashmir and was evidently an extremely limited edition; certainly less than 100 copies, and perhaps only 50 were ever printed; and it is now amongst the rarest of photographically illustrated books on India. A few other, unpublished, views from this expedition have also been identified.

The expedition was also well documented in Colonel H. Torrens’s own book of the expedition: ‘Travels in Ladak, Tartary and Kashmir’, published in 1862.

Clarke later went on to contribute some portrait studies of Indian native types for ‘The People of India’, published from 1868-75, but he died on Feb. 1st 1878, at the age of 44.

Captain Alexander Brodie Melville

The next photographer known to have worked in Ladakh, is the surveyor, Captain Alexander Brodie Melville (b. circa 1834 – d. 1871); an officer in the Indian Army. He was of Scottish origins, and joined the East India Company’s army in 1852, serving with the 67th Native Infantry. He later joined the Trigonometrical Survey Department, and from 1857 to 1864, worked as an Assistant Surveyor on the Kashmir Survey. He seems to have taken up amateur photography at this time, and whilst working in Ladakh, produced a series of half-stereo sized portraits of the Lamas wearing ritual dance costumes, taken at Hemis Monastery, near Leh. The precise date that these images were taken is unclear, but most probably in 1863 or 1864, as the Kashmir Survey was working in Ladakh during this period, and had completed the Ladakh Survey by the end of 1864. A series of ten of these images by Melville were later published in the Bengal Asiatic Society’s Journal, to accompany an article written by his fellow Survey Department officer Capt. H. H. Godwin-Austen, ‘Description of a Mystic play, as performed in Ladakh, Zascar, &c. (Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, vol. 24, no. 2, 1865, pp. 71-79). They were issued as mounted albumen prints, tipped into the journal. These appear to be only known photographs by him, although there may very well be further work by him, of Ladakh, Kashmir or elsewhere, but they have yet to be identified.

This small body of work by Melville appears to be the second series of photographs ever taken in Ladakh; having taken the first Ladakh photographs, so far identified. The similarity between Melville’s name and Captain Robert Melville Clarke, and fact of them having worked in the same region, at nearly the same time, has frequently led to confusion, and occasional misattribution of Melville’s Hemis monastery photographs to Clarke.

Capt. Melville later went on to work on surveying in Central India until 1866, when he joined Capt. James Waterhouse, another famous name in Indian photography; to help establish the Survey Department’s Photographic unit, in Calcutta, having previously studied photo-zincography at the Survey of India HQ in Dehra Dun. They worked together to introduce the use of photography in the production and photolithographic and photo-zincographic printing of Survey of India maps. After Waterhouse left on sick leave in March 1867, Melville took over running of the Photographic establishment, and substantially re-organised it, until Waterhouse returned to duty there in February 1869. Melville then left on sick leave himself, returning to England, where he married in 1870, but he appears to have died in the following year.

Dr. George Henderson

Born in Scotland, in 1836, Dr George Henderson studied medicine at Aberdeen University, before joining the East India Company. He arrived in India in 1859, as a regimental medical officer, before becoming Superintendent of the Lahore Central Prison. He later became Professor of Surgery, at Lahore University, and as keen amateur botanist, travelled extensively through the Himalayas on plant hunting expeditions. He evidently developed an interest in amateur photography, and a passing reference in the diary of the Moravian missionary Maria Heyde, records that he passed through Keylong on August 24th 1869, pausing to photograph the Rev. Pagell with the missionary families there, whilst on an extended tour through the Himalayas to Ladakh. He then went on to take photographs at Leh, Shey Gompa, and at Thikse.

The following year he was the Medical officer and Botanist on the Forsyth’s Lahore – Yarkand Expedition; and sent many plants specimens to Kew. He later documented his part in this expedition, in a book co-written with Allen O. Hume, the noted ornithologist: Lahore to Yarkand: Incidents of the Route and Natural History of the Centuries Traversed by the Expedition of 1870

He went on to become a Director of Royal Botanic Garden, Calcutta, in 1872, and was later appointed Professor of Botany, at Calcutta University.

After retiring, he produced a set of 175 lantern slides of his travels & work, taken all over India during this period, which he used for slide lectures in the UK, from which these few images by him are taken; fortunately these include his pictures of Pagell and fellow Keylong missionaries. Although of poor quality, they give a unique and fascinating insight into life at the Moravian Mission. Some of his topographical photographs of Leh were also used as the basis for woodcut book illustrations, however original prints by him are now very rare. He died, in Inverness, in 1929.

Henry Cousens Senior

After working initially as a Hampshire agricultural labourer; in 1847, at the age of 21, he enlisted as a Private in the Sappers and Miners, where he eventually trained as a photographer and photo-zincographer. From 1858 to 1861 he was working for the Ordnance Survey in Southampton, and became a printer of some note. In 1867, at the age of 41, he was appointed Superintendent of Photo-zincography, to the Government of India; where he served for 14 years, until 1883, when he retired to England. Although primarily working in India as a photo-zincographer, he seems to have done a certain amount of photography as well, at least on an amateur basis. A collection of topographical views, (in varying sizes, from circa 6x4in. up to 10x8in.), of the Himalayan regions of Lahaul, Kulu, & the Kangra Valley, has been attributed to his hand. Many are varyingly signed in the negative HC or HBC (his middle name has still not been confirmed, so there is still a slight element of uncertainty in this attribution).A series of photographs at Keylong, Triloknath and other villages in the Chandra and Baralacha valleys are attributed to him. These seem to all date from circa 1867-69.

Capt. Edward Chapman, together with Capt. Henry Trotter was the official photographer on Forsyth’s second expedition to Yarkand & Kashgar in 1873, and produced over half (86) of the 102 illustrations to the official report. The other remaining images were taken by Capt. Trotter.

En-route, Chapman produced a short series of views of Ladakh, primarily in Leh and surrounding countryside. His photographs from the book of the Forsyth Expedition include a variety of views of Ladakh, including: Lama Yuru, Nimmoo, Leh, The Indus Valley The Ex. Raja of Ladakh and family; Shémurs of Ladak, group of ladies taken at Leh. , Professional dancers of Leh, the Nubra Valley, Buddhist temple at Panamik, Heads of Ovis Ammon, etc.,

A brief chapter (Chapter X) of the report by Captain Chapman supplies some fascinating information on the photographic side of the mission’s work. He writes that when the mission was first formed it was decided to hire a ‘qualified Native Photographer’ to document the expedition. This however proved difficult and it was therefore decided that members of the mission would undertake the work. Chapman and Trotter, therefore, ‘provided themselves with cameras and chemicals, etc., for the preparation of some 400 plates.

After consultation with the photographers Bourne & Shepherd of Simla, it was decided to use the standard wet plate process. Charles Shepherd was also ‘good enough to devote a good deal of time during May and June 1873 to Captain Chapman’s instruction’ It was also decided not to attempt any printing during the expedition, but to send the negatives to Bourne & Shepherd, who would carry out the work. All cameras, chemicals and processing equipment were carried by mule throughout the journey. As to the photography itself, ‘the greater number of the photographs obtained have been taken with Dallmeyer’s wide-angle lens, the slide of the 7¼”x4¼” camera having warped so much under the weight of stereoscopic lenses, which were also provided, as to render them useless. The total number of negatives obtained was 110…

Among the difficulties encountered during photography in the field were weather conditions, and Chapman emphasises that ‘the severity of the winter season and the difficulties attending photography on the line of march need to be appreciated;‘ however, ‘in favour of the equipment and the process employed, it may be recorded that some of the negatives were obtained when the thermometer showed many degrees of frost, and that the camera was constantly used after a long march.‘ The religious sensitivities of the inhabitants had also to be taken into account, and in the main body of the report Forsyth notes that the missions scientific instruments – ‘theodolites, photographic cameras, etc.‘ – ‘might be looked on as only instruments of the black art.’

The official Report of this Expedition was later published, containing over 100 mounted albumen print photographs, and is nowadays another extremely rare photographic work.

Captain Charles McWhirter Mercer (R. A.)

Was an amateur photographer, who initially served in the Bengal Artillery, and took photographs in the Punjab and western Himalayas, in the early 1860‘s. In 1861 he was briefly in charge of the Kulu sub-division. (nov. 1860 – April 1862), and in 1863; was recorded as living at Juggatsukh, and photographing native servants from the Keylong Mission station in Lahoul. (ref: Maria Heyde’s diary, 12th Feb. 1863.) In January 1864 he was appointed curator of the Punjab Exhibition at Lahore.

By 1867 he was serving as ADC to the Lt. Governor of the Punjab, and eventually in 1878, retired to Scotland, with the rank of Major General: where he died in 1884.

He produced and published a series of stereocard views of Lahaul and the Kulu valley, with printed labels to the reverse: ‘Views in Kooloo, Lahoul and Chumba, by Captain C. M. Mercer’, but his work is extremely rare. Images by him, known of so far, include views at Juggutsookh, Triloknath, Burmawaur, and other places in Kulu and Lahaul, as well as some portraiture. Whether he also worked in central Ladakh is not known although quite possible.

The Moravian Missions in Ladakh & Lahoul

The early Moravian church missionaries, based in Keylong and at Leh, although not photographers themselves, were well aware of the publicity potential of photography for fund raising and promotion; and used the work of other photographers and studios, including Bourne & Shepherd, Philip Egerton and Capt. Mercer. The Rev. Heyde, who had accompanied Egerton on his expedition to Spiti in 1864, later sent copies of Egerton’s photographs of Spiti back to the mission’s headquarters at Herrnhut, in Germany, for their archive, and for potential publicity use. Later missionaries such as the Rev. A. H.Franke were competent photographers and did produce a certain amount of good quality views of the region. Becker Shaw was an English born missionary, raised and educated in Germany who also worked with the Moravian Mission in Ladakh from about 1890 – 1895. He was a very competent photographer and took a number of studies of the country and mission work, some of which were used in the Moravian Mission’s publicity material.

Samuel Bourne, and Bourne & Shepherd studios

One of the greatest names in early India and Himalayan photography is that of Samuel Bourne, co-founder of the Simla & Calcutta studios of Bourne & Shepherd.

He made three major expeditions through the Himalayas, between 1863 and 1866, and although he didn’t visit Ladakh, he did travel on its outer fringes, visiting Kashmir in 1864, up as far as the Zoji La, where he produced some spectacular mountain landscapes. Whilst in Srinagar he made a small series of portrait studies of the local peoples, including two images, supposedly of Ladakhis visiting Kashmir, but who appear to actually be from Baltistan or the islamic regions of greater Ladakh. The majority of the portraits by other professional studios produced at this time and labelled as Ladakhis, were also of Baltis or central asian moslems, rather than Buddhist Ladakhis.

On his 3rd expedition in 1866, he travelled through Kulu and the southern borders of Lahaul, along the Chandra and Spiti Valleys, again producing a fine series of iconic Himalayan landscapes.

Francis Frith & Co.

The English photographic publishing company Francis Frith and Co.; as part of their worldwide series of topographical photographs, from the late 1850’s onwards, commissioned several photographers to travel to India and produce work for them. One of these, Frank Mason Good, travelled to Kashmir in 1870-1871, where as well as making local views, he made several fine studies of Ladakhi visitors to Srinagar. He then travelled through Kulu and Spiti, producing a very fine series of views of the Spiti Valley, again including portraits of Ladakhis visiting there. These prints were marketed primarily in England, but also were on sale through local agents in India.

1875 -1895 ‘The blank period?’

After an initial period, from 1861, through until about 1873, when a limited progression of photographers primarily amateur and semi-professional, visited the region, we seem to enter a veritable ‘dark age’ through the 1880s’ and early 1890s’ when, for some unknown reason, and despite the invention of cheaper, simpler and more portable photographic process and cameras, there seems to have been little or no discernible photographic activity in Ladakh at all. No professional studios were established in Leh or Kargil, and few if any travellers seem to have brought back photographs of the region. From the 1890s’ onwards, this slowly started to change and increasing numbers of visitors returned with views of the region, although still primarily of Leh and the major monasteries. The more remote areas remained completely undocumented until well into the twentieth century.

A variety of ethnic portraits and topographical views are known, largely by anonymous photographers, and hard to date precisely; some may be from the 1880’s, but most appear to date from the turn of the century.

Various Other Photographers and Studios. 1890’s 1930’s

One of the few professionals to visit the region at the turn of the century, was P. Vishi Nath, of whom, sadly, very few details are known. He was a Srinagar based professional photographer, active from about 1900 for twenty years or more. Apart from producing the usual studio portraiture, he also made one or more trips to Ladakh, producing a range of good quality topographical views of Leh, Hemis, and the surrounding countryside, which were marketed in his studio in Srinagar. His work was also used to illustrate the book Kashmir in Sunlight & Shade by C. Tyndale-Biscoe, which was published in 1921.

Geoffroy Millais was the son of John Millais the pre-Raphaelite painter. A keen and talented semi-professional photographer, he spent some time in India, during the 1890’s, primarily in Kashmir, and produced a body of fine landscape photographs of the region, including Ladakh.These were marketed as large platinum & gelatine prints up to 20 x 16 in in size. His work was used to illustrate the books Picturesque Kashmir’by Arthur Neve, published in 1900 and Kashmir in Sunlight & Shade’by C. Tyndale-Biscoe.

Later Views – postcards etc.

From the 1900’s onwards, an increasing number of people visited Ladakh and used a camera to document their journey. Many of them sadly remain anonymous, but a range of photographs appear in private snapshot albums, and surface now and again, and some were sold as postcards.

From the 1920’s onwards, occasional press photographs appear, of people and views; primarily in Leh, for reproduction in magazine and newspapers. Mostly with the photographer uncredited, just the picture agency.

Mrs Eliza. H. Read served as a Matron with the Central Asian Mission, and was a very competent amateur photographer being the daughter of a Swiss professional photographer. She was married to Dr. Alfred Charles Frank Read, (author of ‘Balti Grammar’ pub. 1934), and they worked together in Kashmir, as medical missionaries in Srinagar, from the mid 1920’s to the 1940’s, and spent much time working amongst the local communities. She documented village life and portraits of local people; both in Kashmir Baltistan and Ladakh. A very little of her work was published in the Illustrated London News, but the bulk of her surviving images remain in the Read family archive.

Rupert Wilmot. a British army officer, made two trips around Ladakh in 1931 and again in 1934.. A very competent amateur photographer, he produced a fine body of work documenting the landscape and peoples of Ladakh. Although not sold commercially, they were eventually published by his family in 2014, in ‘The Lost World of Ladakh. Early Photographic Journeys in the India Himalayas 1931 – 1934.’

By the 1930’s onwards, a steadily increasing number of travellers took a camera with them and the area began to be documented more thoroughly; however, in comparison with other parts of India and the Himalayas, Ladakh was still one of the most poorly photographed regions.

Much study remains to be done of Ladakh’s early photographic history, and the little research that has been done so far, has barely scratched the surface.

Hugh Rayner is a private collector, researcher, dealer, publisher, and photo-historian, specialising in the early photography of India & South Asia.

For further information, visit: www.indiaphotographs.co.uk.

Bibliography

- Falconer, John. Ethnographical Photography in India 1850-1900. Article pub. 1984 in The Photographic Collector 5(1):16-46.

- Falconer, John. The Waterhouse Albums. Central Indian Provinces. Pub Alkazi Collection/Mapin Delhi 2009.

- Biographical index published in ‘From Bombay to Shanghai’. Pub. Stichtung Fragment Foto, Amsterdam, 1995.

- East India Register for 1855, 1860, 1865, 1867, 1870. Bengal Army List 1859.

- War Services of the Officers of the Bengal Army. pub 1863.

- Markham, C. R. A Memoir on the Indian Surveys. pub. London 1878.

- Rayner, Hugh, & Bourne, Samuel. Photographic Journeys in the Himalayas, Letters by Samuel Bourne 1863-66. Pub. Pagoda Tree Press , Bath, 4th ed. 2014.

- Rayner, Hugh. Early Photographs of Ladakh. Pub. Pagoda Tree Press 2012,

- Rayner, Hugh. Frith Series: Views in Kulu & Spiti, pub. Pagoda Tree Press 2013,

- Bates, Roger & Harman, Nicky. The Lost World of Ladakh. Early Photographic Journeys in the India Himalayas 1931-1934. pub. Stawa Publications, Leh, Ladakh 2014. ISBN: 978-81-909004-2-3. (Also now available online as a free pdf download)