In Mexico it is believed that a person does not really die until their name is spoken for the last time. I must say I like the idea since it seems to give some purpose to the articles I write. As a photo historian I love digging the past and finding out information not only about the photographers and their work, but also about the sitters whose likeness they took. This is what decided me to write this column, to drag these little-known people from oblivion and give them, so to speak, a second lease of life. They may not have made history or become famous but they lived on this earth at some point, loved and were loved, laughed, cried, had fun, suffered, took photographs, or sat for them. This, in my opinion, is enough to make them worth being remembered.

I love ambrotypes, always have, and always will, I guess. Although not so ancient, they are as sharp as daguerreotypes and do not have the mirror-like surface of the latter, which makes them easier to see and study. Mind you, I have nothing against daguerreotypes but they are usually way beyond my means whereas ambrotypes are generally more affordable. As I have written before, I am not a collector and only buy photographs, whether on paper, glass or metal, when I know – or at least hope – I can research and write about them.

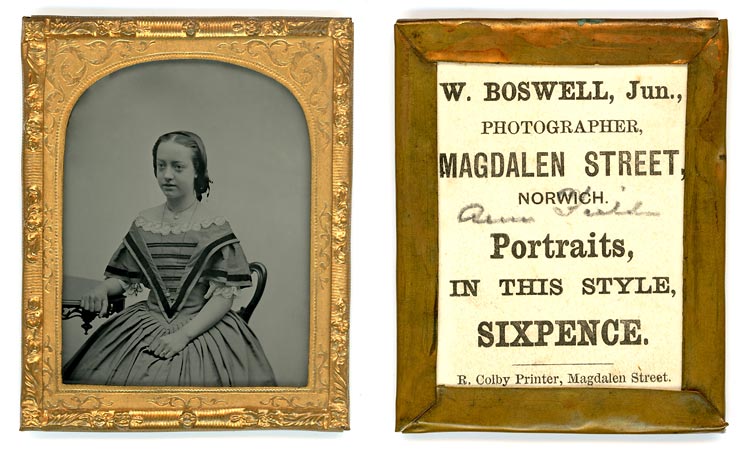

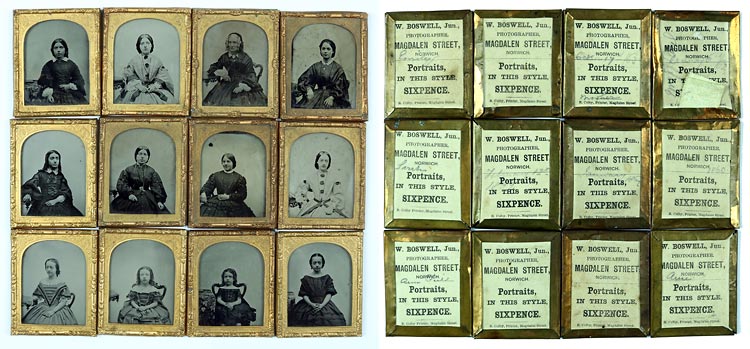

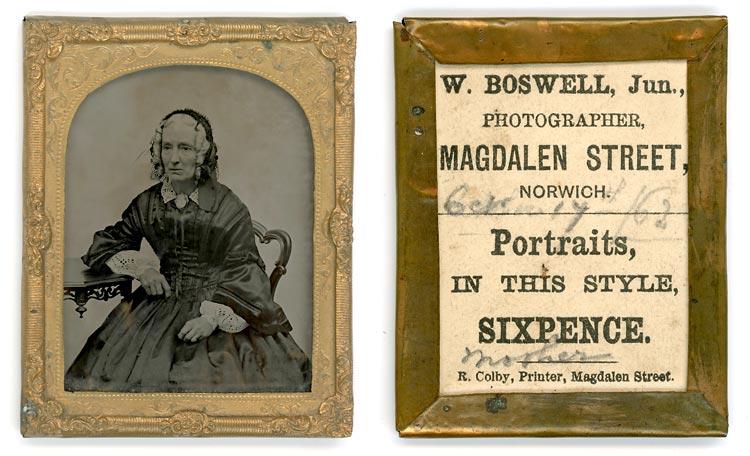

The idea of this article started when my wonderful colleague Rebecca drew my attention to a group of twelve ninth plate ambrotypes that were for sale on eBay as “Buy it now” (not a very common thing, unfortunately) and were described by the seller as possibly representing members of the same family. The images looked nice, the photographer, an artist from Norwich, Norfolk, had printed his name on the backing card that protected them (a rare occurrence since over ninety percent of the ambrotypes I am fortunate to own in my “archive” bear no indication of who took them). Some of the sitters were also identified, or to be more precise, their first name was pencilled on three different occasions while a fourth image bore the mention “mother”, in the same hand. I let a few days pass before I decided it would really be a missed opportunity to let those twelve images go and not try and identify the family members and, if possible, find out as much as I could about them. On a Wednesday morning, as I was waiting for my Uber ride to the airport, I suddenly made up my mind and bought the images. They arrived by post a few days after my return from a 3-D conference in the States where I had given a couple of talks and held a stall for two days. When I took them out of their protective layers of bubble wrap, I realised one extra image, obviously showing one member of the same family, but by a different photographer, had mistakenly been added to the pile.

I contacted the seller at once and let him know I would like to buy that thirteenth image, which I did the very same day. It was then that I became aware that the description of the lot mentioned there were originally twenty of those ambrotypes. Two had been sold separately before I made up my mind to buy the set of twelve, one was still listed on eBay but turned out to be the one which had been added by accident to the parcel that was shipped to me. That left five more images to be got hold of. I therefore contacted the seller again but was told that those images, not in such good condition apparently, had been sold on the previous Tuesday at a market where he was holding a stall. As I have written in a previous part of this Second Lease of Life series, I cannot understand why sellers, be they private ones or auction houses, have no qualms separating members of a family. I am aware they expect to get more money out of it but when portraits have been kept together for over a hundred and fifty years, I find it very sad that they should end up in different homes. Fortunately, this seller had taken photos of the other pieces and very kindly sent them to me so that I could see what the other images showed. Two at least are much more recent, three represent people – all females – from a different family or a different part of the family, and one is a copy of an older image which was re-photographed and shows part of the original passepartout. This is the only portrait of a male sitter but the photograph is not very sharp, which makes it is difficult to see if there is a family resemblance. It is not clear whether it is the reproduction of a daguerreotype or of an ambrotype but I would lean towards the latter. Since there is nothing I can do to get better reproductions unless the current owner of the image sells it, I guess I must consider myself lucky to have collected thirteen out of the original twenty portraits. Here are the twelve I originally bought, front and back, as they appeared immediately after they were unwrapped.

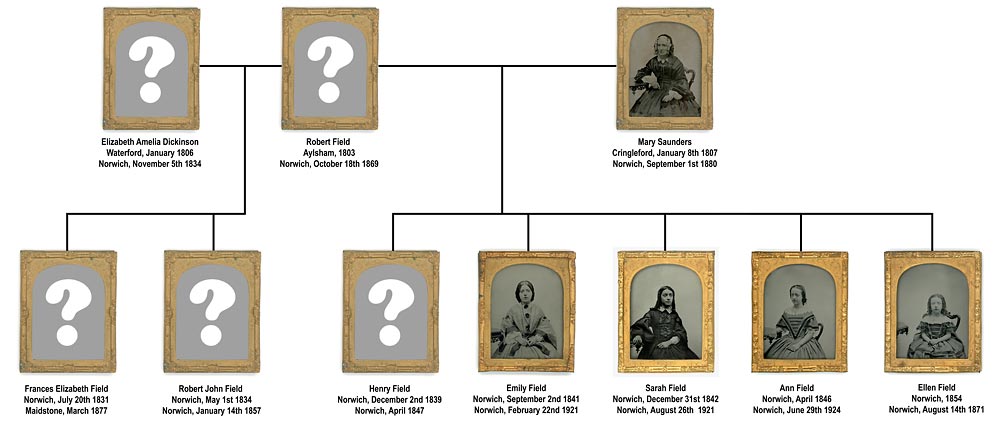

The following weekend I made a list of the three first names I had and since some of the portraits bore pencilled dates ranging from 1860 to 17 October 1862, I figured my best shot at finding the sitters was to try the returns of the 1861 census. The two photographers responsible for the images operated in Norwich, so chances were that the members of the family lived there too, or at least nearby. With the help of Ancestry, I looked for a family who lived in Norwich and whose children’s names were Emily, Sarah and Ann. One of the images bore on its back, in pencil, the name Ann followed by what looked like a family name, the first letter of which looked like an F. Luck was on my side that day and I struck gold almost immediately. I discovered that the three named young women were the daughters of one Robert Field, and of his wife Mary. At the end of the weekend, I knew everything there was to know about the Field family and the photographers they had chosen to capture their likenesses. Before I tell you the story of these people and bring them back to “life”, if only momentarily, let me show you a pictorial summary of my findings.

Mr Robert Field, the paterfamilias, was born at Aylsham, Norfolk, some time in 1803, to John Field and his wife Ann, née Ives. On July 25th 1830, at Norwich, Robert married Elizabeth Amelia Dickinson, born and baptised at Waterford, Ireland, in January 1806. A daughter was born on July 20th 1831 and was given the names Frances Elizabeth. Just under three years later, on May 11th 1834, a son was born, who was called Robert John, after his father and grandfather. Robert John never really knew his mother, who died aged twenty-seven on November 5th 1834 and was buried four days later.

On March 3rd 1839, just a few months before photography was revealed to the world, Robert Field married a second time. His wife’s name was Mary Saunders. She was the daughter of one William Saunders and was born on January 8th 1807. Their first child came into this world on December 2nd 1839 and was named Henry. He sadly died at the age of seven and was buried on May 2nd 1847. On September 2nd 1841, a daughter was born who was given the name of Emily. Mary Saunders-Field bore three more children: Sarah, born on December 31st 1842, Ann, born in the second quarter of the year 1846, and Ellen, born in 1854.

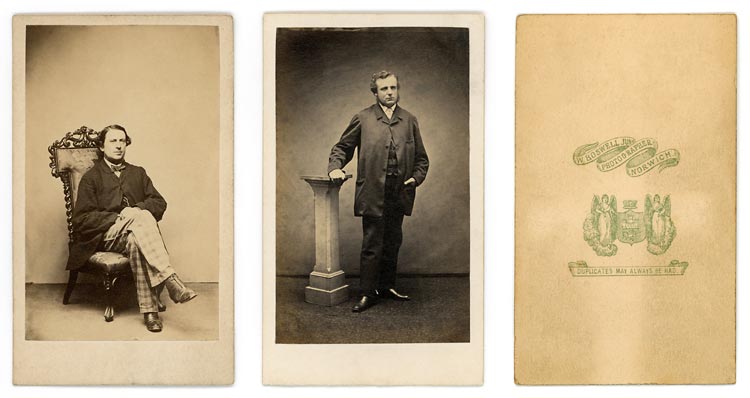

In the 1841 census Robert Field is listed as a Clerk living on Duke Street, in the parish of St Michael Coslany, Norwich. Ten years later Robert Field, aged forty-six, is described in the census return as a solicitor’s managing clerk living on Stepping Lane, Mountergate, Norwich, with his forty-four-year old wife Mary, their five children, Frances Elizabeth, Robert John, Emily, Sarah, Ann, a twenty-one year old visitor, Richard Field, listed as a railway company clerk, and a twenty-six year old servant called Harriet Parnell.

Less than three years after the census, on January 14th 1857, death struck again and took away Robert’s only remaining son, Robert John, who was just under twenty-three. The copy of a photograph of a male sitter which I mentioned earlier might be a portrait of Robert John but there is no way to prove it without examining the original ambrotype. It would make sense, however, that this unique image was reproduced after his death so that other members of the family could remember his features.

Was it Robert John’s death which, in some way, decided Robert Field to have likenesses of his surviving children taken over the years? It is unfortunately impossible to say but the earliest portraits of the Field family, sadly not dated, seem to have been taken in the late 1850s. To fix the features of his daughters for posterity, Robert Field turned to Norwich-born photographer William Boswell Junior.

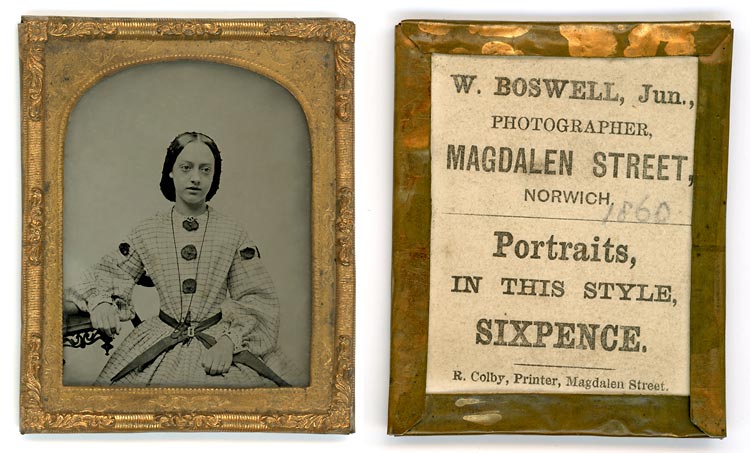

First born child of carver and gilder William Boswell (1810-1877) and of his wife Lucy Cushing (1812-1894), William Junior came into this world on January 14th 1840. By the time he turned twenty he was already a photographer, still living with his parents and operating from their home on Magdalen Street. The first dated photo he made of a member of the Field family – Ann – was taken in 1860 but a couple of what look like earlier images of Emily, Ann and Ellen are also by him. An earlier image of Ann, which I have only seen the eBay photo of, looks even earlier than the ones below but does not have any indication as to who took it.

By the time of the 1861 census the Field family had moved to King Street, Norwich, and its head, Robert, was working both as an assistant clerk to commissioners of income tax and as an attorney’s clerk. His daughters Emily, Sarah, Ann and Ellen were respectively aged nineteen, eighteen, fifteen and seven and Harriet Parnell, now thirty-six, was still providing to the needs of the household as their only servant. Frances Elizabeth, Robert’s only surviving child from his first marriage, had wed a railway clerk on June 15th 1853 and was now Mrs Richard Fryer, a twenty-nine year old mother of three, living with her husband and children at Shrewsbury, Shropshire. Later that same year, 1861, Ellen Field was photographed by Charles James Thompson, who is listed in the census as an ironmonger but must have had a change of career soon afterwards as Ellen’s photograph bears the date 1861 and the blind stamp “C. J. Thompson, Photographic Artist”. This portrait is the unexpected thirteenth image which I found in the packet I received from the seller.

Thompson was born on October 3rd 1839, a few months after Louis Daguerre presented his photographic process to the world, to veterinary surgeon Walter James Thompson and his wife Charlotte Kitton. He was still a photographer in 1871 but by 1881 he had become a picture dealer before appearing as a dentist in the 1891, 1901 and 1911 censuses. It is unclear what prompted the Fields to turn to Thompson for that portrait of Ellen, all the more so as later family portraits were made by Boswell.

The last photo of the Field family Boswell apparently took is dated October 17th 1862 and represents Mrs Field herself. I unfortunately do not know if there exist portraits of Mr Field by the same photographer, or by any other disciple of Daguerre, Talbot and Frederick Scott Archer. Two portraits, also by Boswell, and also taken in 1862, show unidentified young women. They look related to the Fields but I have not found out who they might be. There are no traces of siblings for Robert Field but we know Mary Saunders had two brothers Could these two young women be cousins of the Field sisters?

Robert Field died on October 18th 1869 and was buried next to his son Robert John at the Rosary cemetery where their grave is still visible. Two years later, they were joined by their youngest daughter and half-sister, Ellen, who passed away on August 14th 1871. In the census taken earlier that year, Ellen, then seventeen, was described as a music teacher, as was her sister Sarah. Ann was living with her husband, Norwich grocer William Snelling, whom she had married the year before, on November 3rd 1870. Ann was Snelling’s second wife. His first spouse, Mary Ann Stolworthy, whom he had wed on September 3rd 1860, had borne him three children before passing away.

A rather curious but very interesting fact is worthy of note in the 1871 census return. Emily Field, who was then twenty-nine and still unmarried, is listed there as a photographer’s assistant. Unfortunately, it is not specified which Norwich photographer she was working for. It would have been nice had it turned out to be for the same William Boswell Junior who had photographed her and her sisters several times but it was not. By 1871 Boswell had married and was living in Dartford, Kent, with his wife Emily, née Weekes. He had put an end to his photographic career and was earning a living as an ironmonger! Boswell married a second time after the death of his first wife in 1876 and passed away on January 14th 1889, still an ironmonger and still in Dartford. His second wife, Ellen Mary Bly, survived him by fifty years. She died at Clapton-on-Sea, Essex, on June 30th 1939. It would be nice to know what sparked Emily’s interest in photography but it could be her fascination began when she sat for Boswell.

Frances Elizabeth Fryer, the eldest child of Robert Field, died in the first quarter of 1877, aged forty-six. Her stepmother, Mary Field, née Saunders, was the next family member to pass away. She breathed her last on September 1st 1880 and was buried next to her husband and daughter Ellen. Emily and Sarah never married. I could not find any trace of them in the 1881 and 1891 censuses so that I cannot tell you how long Emily remained a photographer’s assistant. The two siblings were still in Norwich in 1901 and 1911, living in the same house, on their own means. Emily died on February 22nd 1921 and her sister Sarah passed away the same year, on August 26th. They were then living at Barbary Cottage, Rosary Road, close to the Rosary cemetery where they were buried along with their parents, sister and half-brother. Ann was the last one to leave this earth. She died on June 29th 1924 and is also buried in the same cemetery but in a different plot.

I am still uneasy about the disappearance of the seven images that were originally with the thirteen portraits I managed to acquire but I am glad to have given a name and a story to those faces and people from another era when they were fewer photographic traces of family members and photographs were considered precious enough to be kept together and cherished.