This text first appeared as an exhibition review in the Burlington Magazine, October 2017.

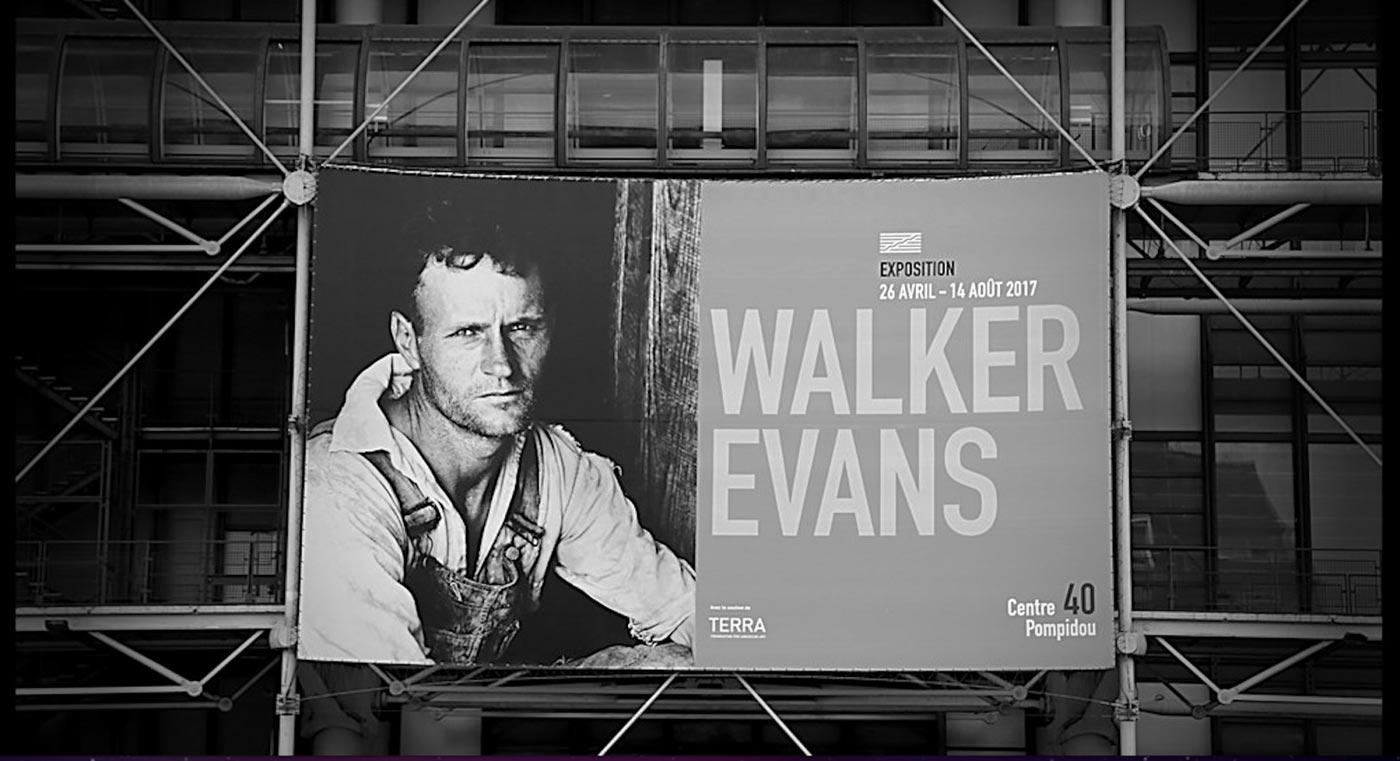

A giant banner showing the handsome and haggard face of Alabama Tenant Farmer Floyd Burroughs, (1936) arrests the visitor outside the Centre Pompidou. It announces the comprehensive exhibition of the work of American photographer Walker Evans (1903-1975).1Walker Evans, exhibition at Centre Pompidou, 27 April – 14 August 2017. Touring to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 23 September 2017 – 4 February 2018. The image was taken by Evans as part of an assignment for Fortune magazine to explore the daily lives of sharecroppers in the American South. It appeared alongside other brilliantly edited sequences of images from the assignment by Evans in the book, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941). Critically acclaimed, the book is an extraordinarily honest and moving account of the Great Depression era, and an innovative collaboration between Evans and the writer James Agee. Evans and Agee achieved a finely-tuned balance between literary and visual journalism and personal expression. Evans stark portraits from Alabama have since come to define the visual identity of this chapter in American history. While they have justifiably become the most totemic photographs within the photographer’s long and lauded career, they have also unevenly tilted the popular perception of Evans in the direction of photojournalism. The Pompidou’s impressive retrospective instead convincingly makes the case for Evans as a modernist artist with a lifelong conceptual and personal project linked by the theme of ‘the vernacular’.

The exhibition shows how Evans adopted the vernacular both as a subject and as a working method. Vernacular is taken here to mean a concentration on the indigenous, poor, humble or utilitarian, the democratic and the popular. Evans was drawn to subjects of low financial worth but that exemplified what he called ‘accidental beauty’. In particular, he sought subjects that might define a distinctly American character. The vernacular subject appears for example in utilitarian architecture, hand-written signage, common tools and in the physical character types seen in his photographs of people. Using the vernacular as a working method, Evans attempted to disappear as an artistic presence by appropriating the style of postcard views, commercial portraiture, catalogue images or architectural photography. There is a deliberately frank and detached coolness in Evans method that extends throughout his career and which he called ‘documentary style’. Of course, this attempted neutrality in itself became a recognisable style. The exhibition is arranged broadly chronologically and by commission or personal project. The main sections are titled: ‘A Classic Modernist’; ‘Victorian Architecture’; ‘Facades, Posters, Signs’; ‘The Humble’; ‘Ruins’; ‘Doors, Monuments, Churches’; ‘Masks and Tools’; ‘City Dwellers’ and ‘Photography Itself’. The arrangement enables the visitor to witness Evans’ vernacular subject matter and style unfolding in parallel as a coherent connecting device. Evans’ appreciation of the vernacular also led him to collect artefacts, such as hand-written notices, rusted advertisement signs, commercial portrait photographs, and postcards. Constellations of these – and blow-ups showing the interior of Evans’ home with them on display taken the year he died – are gathered in the exhibition and give a further dimension of Evans’ visual references.

In his pursuit of the vernacular, Evans was reacting against self-conscious art photography of the kind practiced and promoted by Alfred Stieglitz. For Evans, true lyricism entered spontaneously or was discovered after the fact. Evans became a master of what has subsequently been described as a ‘deadpan’ approach, a deceptive simplicity filtering out nostalgia and sentimentality, showing seemingly mundane subjects that actually reveal vital details. Evans had a knack of dovetailing his own artistic manifesto with his commissioned work. His seminal photographs made for the Farm Security Administration, ostensibly to provide a photographic survey of rural America, satisfied his own agenda. Another less famous but striking example is his portfolio of 477 photographs commissioned by the Museum of Modern Art in 1935 showing African sculpture. A set of these images was acquired at the time by the V&A, seen squarely then as documents of sculpture but recognised today in their dual capacity as part of Evans’ own visual lexicon.

The majority of Evans’ photographs were intended originally for, or first seen on, the printed page rather than as framed prints in a gallery. Consequently, Evans was used to working with commissioners, editors, designers and typographers. Arguably, his work is best seen and understood in its published form. The book American Photographs, accompanying his one-person exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 1938 became a touchstone of photographic publishing. However, the Pompidou’s exhibition focusses instead on the equally exciting though lesser-known spreads he created for Fortune magazine. Surprisingly, Evans often wrote the excellent texts accompanying these pieces that were photographed in black and white and also sometimes in colour, probably to satisfy the expectation of a magazine-reading public. As a legacy of the exhibition, the Pompidou has acquired these magazines for its permanent collection from writer and curator David Campany who has published an illuminating book on the subject.2David Campany, Walker Evans: The Magazine Work, Steidl, 2011 Among the many fascinating examples of original photographs shown next to the magazine and book spreads that stand out are, Labor Anonymous (1946), a serial study of workers walking in the streets of Detroit, and Rapid Transit / Subway Portraits (1956-66). These works demonstrate that Evans’ sequences, showing the cinematic influence of newsreels, deserve as much attention as individual images. At the opposite end of the scale, two iconic portraits of Allie Mae Burroughs (wife of Floyd) have an entire room devoted to them. The difference between the two exposures is almost imperceptible, but we are informed that one portrait is marginally ‘more smiling’ than another.

The curators Clément Chéroux and Julie Jones, and supporters the Terra Foundation for American Art, should be praised not only for presenting Evans in such a coherent light, but also for the huge task of coordinating the necessary loans. Evans was not especially precious about making fine prints himself, and many of his works printed later by others can be found and it is still possible to obtain new prints of some of his work from the Library of Congress. It would have been easier and less expensive to use a large selection of modern or later prints from one or two sources. But the selection here is of prime vintage material, as Evans would have seen or made it in the first place. It is a pleasure to see material from major museum collections, from the J. Paul Getty Museum and most notably from the Walker Evans archive at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, as well as those from numerous private collections. In total, there are thirty-eight separate lenders to the show, with around eighty percent from the US. The expansive exhibition catalogue is a wonderful legacy of the show.3Clément Chéroux (ed.) Walker Evans, Text by Clément Chéroux. Contribution by Anne Bertrand and David Campany and Didier Ottinger and Jeff L. Rosenheim and Jerry L. Thompson and Julie Jones and Svetlana Alpers. Prestel, Lakewood, USA, 2017. In English. 320 pp.

Little of Evans’ personal biography is explained in the exhibition, though its broadly chronological sweep charts where he was living and working. And except in some instances where his friends appear in late Polaroids, his photographic subjects resist personal biographical readings, withholding signs of the author, exactly has he wanted. What is conveyed however through the vast gathering of his images, and a revealing film interview at the end of the exhibition, is Evans’ maverick attitude, and traces of a decadent dandy character. Evans came of age in the fragmenting modern world of James Joyce in Paris in the 1920s and continued with an experimental and literary attitude towards photography throughout the twentieth century. His wry photographs showing handwritten signs act like accidental advertising slogans. They are, like Evans himself, witty, incisive, physically slight but evocative of a whole American culture. A sign on a door reads, ‘Office for Rant’; another commands, ‘No Guning’; and a sign hovering in a tree proclaims, ‘Christ or Chaos?’ Evans’ own words resonate too as a call to be more visually alert: ‘Stare. It is the way to educate your eye, and more. Stare, pry, listen, eavesdrop. Die knowing something. You are not here long.’4Walker Evans, ‘People Anonymous: People in the Subway: Unposed Portraits Recorded by Walker Evans’, draft introductory unpublished text, printed in Walker Evans at Work: 745 Photographs Together with Documents Selected from Letters, Memoranda, Interviews, Notes, Essay by Jerry L. Thompson, New York, 1982, p.161.

Martin Barnes is Senior Curator of Photographs at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London.