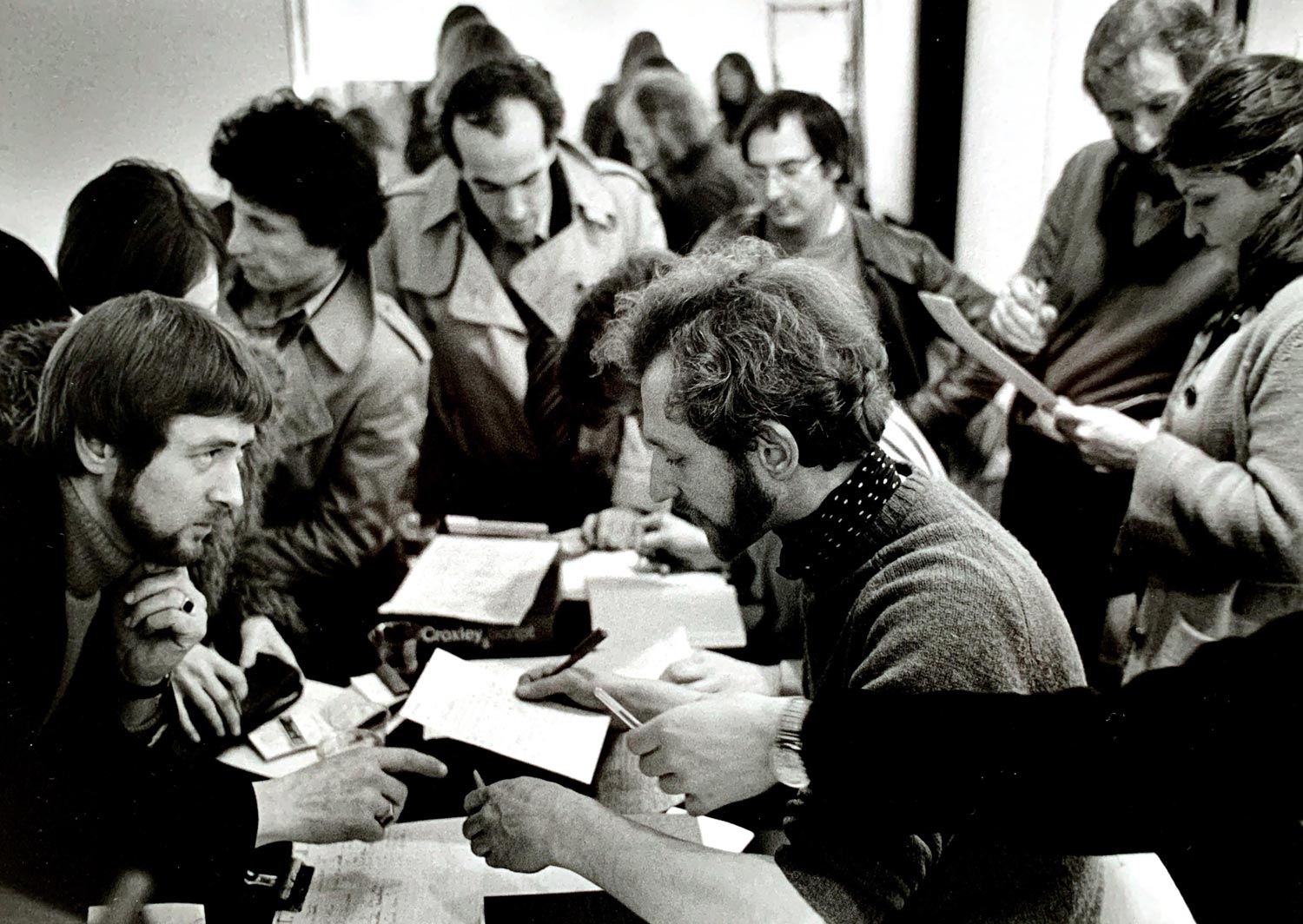

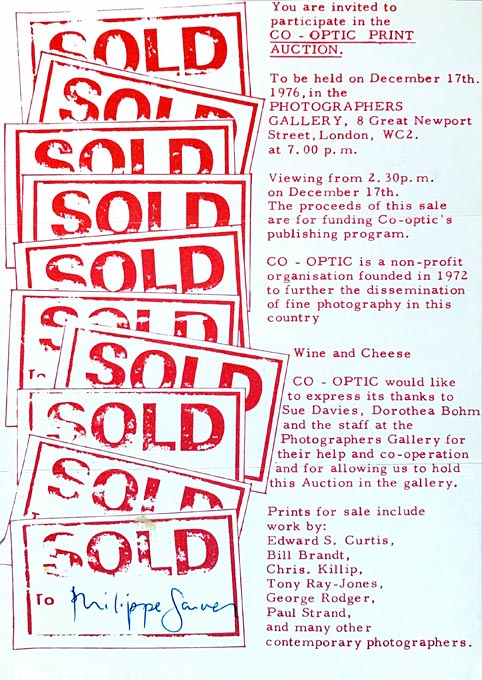

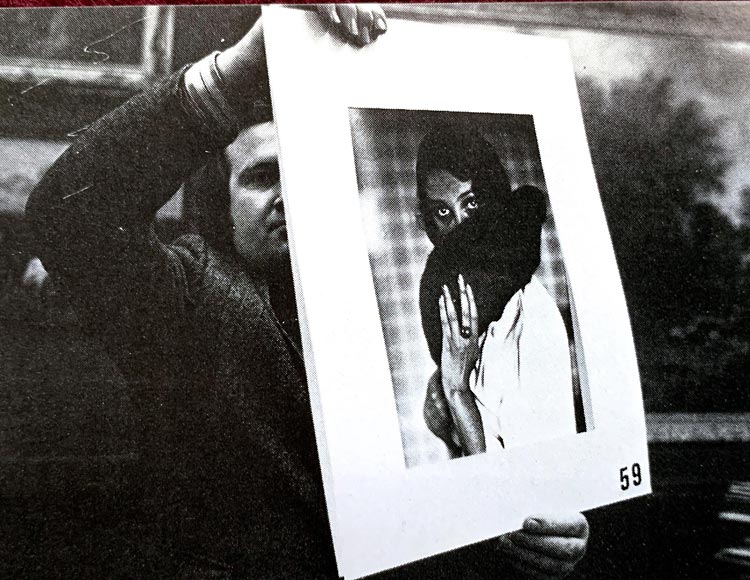

My memory is hazy on the circumstances of my first visit to The Photographers’ Gallery. Forgive me, but it was half a century ago. Fortunately – or so it seemed – I found on the Gallery’s website some time ago a photograph that evidenced my presence at 8 Great Newport Street as far back as 1971, the founding year. The picture was by Homer Sykes and his caption specified the year. In response to my search for more information, Homer identified the context as a fund-raising print auction organised by photographer Stephen Weiss for the documentarist group Co-Optic and hosted by The Photographers’ Gallery. So far, so good. But when going through my diaries of the ‘70s and ‘80s to verify dates and details for this essay, what should I find, tucked into the page for December 17th 1976, but a dated flyer for what appeared to be this very auction. To clarify the matter, I called Homer and asked him to double-check his dating. He went to the original contact sheet and apologetically confirmed that the correct date of his photograph was indeed 1976. We laughed at this revelation of the potentially slippery nature of photographs as evidence, a pertinent cautionary tale in the present volume and one which Homer has, with good grace, allowed me to tell.

In 1971, I was in at the deep end of a new profession. I had joined Sotheby’s as a trainee the year before. I was given a job in March 1971 as a junior specialist in late 19th and 20th century decorative arts. That summer, I was assigned responsibility for cataloguing and coordinating a pioneering sale of historic photographs scheduled for later in the year. The sale, on December 21st, marked a strategic decision by the company to establish regular auctions in this hitherto largely overlooked field. The focus in that and subsequent sales was on the masters of the 19th century, about whom I knew little when I started out; but I learned fast by handling and cataloguing their work. My curiosity about photography and the culture of images dated back to the early 1960s and was insatiable, but what knowledge and appreciation I had was essentially concentrated on modern and contemporary practitioners. My appetite for images was largely fuelled by current magazines – from Town, Queen, and Vogue via such titles as Paris-Match and Twen to the newspaper colour supplements that started to appear in 1962.

Now working in the field of photography, I soon heard of The Photographers’ Gallery, a new beacon for contemporary photography, and I became a frequent visitor, getting to know first the Director Sue Davies and then Dorothy Bohm, a committed friend to the Gallery. The tone was very effectively set by Sue’s enthusiasm and engaging manner. She was without pretension or ego, evidently determined, but with an openness and informality that drew people easily to her. Sue made you feel welcome and involved. Dorothy, some years her senior and with long experience as a photographer, brought her own deep-rooted passion and positive energies to the Gallery project. I was charmed by both of them and was only too pleased to enjoy 8 Great Newport Street as a hub for the pursuit of shared interests.

Sue introduced me to members of her ever-growing circle, which of course included photographers of every stripe. I remember well, for example, and cherish the memory of a brief encounter with the ethereal Bill Brandt, noting his whisper of a voice and his gentle, enigmatic smile. In marked contrast, I recall the jovial, solid presence of his more down-to-earth contemporary Bert Hardy. Sue would host casual kitchen-table meals in her top-floor flat above the Gallery. One such, on June 30th 1981, was with the ever-cantankerous but always stimulating William Klein and the equally contrary Brian Duffy. With hindsight, I appreciate how privileged were these opportunities to be welcomed into so vibrant a milieu. I can also see more clearly how intuitively good Sue was at finding her way, bringing people together, and winning support. She trusted her judgement but was never autocratic; she was always open to fresh ideas and sensibly weighed up the input from those around her. Dorothy, meanwhile, loved to share her personal experience and her profound emotional engagement with the medium. She was instrumental in developing pro bono the Gallery’s book and print sales, at first working out of a space that was little more than a cupboard.

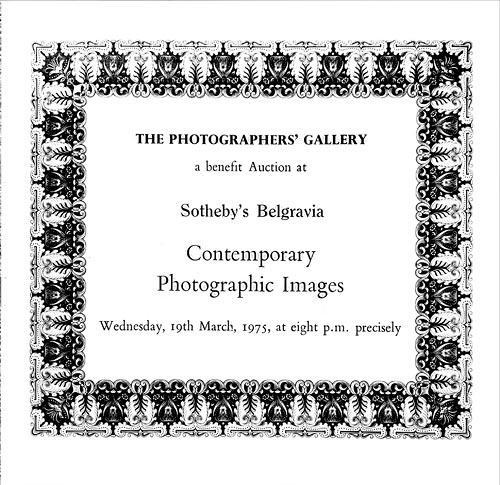

The Gallery was a success, but funding was a constant challenge. In the autumn of 1974, Sue asked me if I would be able to help organise and host a benefit auction at Sotheby’s. The idea was to ask a wide range of contemporary photographers to submit prints for this fund-raising event. I first ensured that I would have the company’s support and, once this was secured, I gave Sue the green light for an auction the following spring. Her requests for submissions went out to a wide range of photographers from Britain, Europe, and the USA. The eventual catalogue of one-hundred-and-one lots was a Who’s Who of some of the most notable practitioners of the day. Many of these have since consolidated stellar reputations, among them Ansel Adams, David Bailey, Cecil Beaton, Bill Brandt, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Bruce Davidson, Lee Friedlander, Robert Frank, Don McCullin, Helmut Newton, and Irving Penn. Certain others, talented and well regarded in their day, have not maintained their visibility to the same extent. Such are the vicissitudes of the profession.

The auction was a landmark event for contemporary photography, a harbinger of future trends. Virtually all of the photographers featured in the sale made their living and found their audience through the printed page. A number of them were to establish significant positions in the coming years in the developing market for fine prints, but for most of the photographers involved, this was the first time their work had been presented at auction. The sale, titled ‘Contemporary Photographic Images’, was scheduled for Wednesday March 19th, to coincide with one of our now-regular auctions of historic photographs, in the expectation of drawing in as bidders some of our established clients. Sue came over to Sotheby’s Belgravia in the afternoon of the previous Friday to hang the sale, not without some trepidation – this was uncharted territory and success was by no means guaranteed.

The evening auction drew a good audience. The red cloth walls were hung with Victorian paintings, on view for an upcoming auction, creating a colourful ambience. From the rostrum, I could take stock of the room’s potential and was particularly pleased to see, among the many likely bidders, prominent American dealer Harry Lunn and today-legendary collector Sam Wagstaff, both of whom were to buy several lots, with Wagstaff setting the highest price of the sale – the £260 he paid to secure Penn’s portrait of Colette. Quite a number of prints were bought by photographers caught up in the excitement of this significant moment for their profession. They included John Benton-Harris, Lester Bookbinder, Terence Donovan, Barry Lategan, and Norman Parkinson, who bought the Cecil Beaton print. An anxious Sue Davies had taken her place near the front of the room, sitting discreetly to my left on the floor behind an ornate grand piano, an upcoming lot. Her tension at the start of the sale soon eased as she followed the competitive bidding for the material on offer. The auction – so crucial, for the financial stability of the Gallery – was heading in the right direction. The eventual total exceeded expectations and a small group of us celebrated with a late dinner at the super-chic Chelsea restaurant Factotum, where Sue was in a delighted daze.

The single most significant personal consequence of the auction was the context it gave me to make contact with Helmut Newton, whose work I had greatly admired since the late 1960s. His first solo show had opened in Paris the day before our auction. An introduction was effected and we met in Paris on April 7th. We got on well and this first encounter was to develop into a friendship that lasted till Helmut’s death in 2004. I was thrilled to see his Paris exhibition and to discuss it with him and his wife June, both hungry for the fresh perspective of critical feedback from a young British auction specialist who by now knew something of the broader history of photography. At some point later that year, I ran past Sue the idea of her hosting an exhibition of Helmut’s work. Respectful of his established status in his field, and always herself committed to the full range of editorial imagery, she said yes. The exhibition was scheduled for January 1976.

The opening, on January 7th, became also the celebration of the Gallery’s fifth birthday. The day before had been busy with the installation of Helmut’s pictures, and I joined him and June in the Gallery in the afternoon to have a first look. Terence Donovan dropped by to pay his respects to Helmut, and promptly bought one of the prints. What better way to show his appreciation? That evening, I hosted a party for Helmut and June in the large garage of the mews house in Marylebone that I called home. With a juke-box in the corner and a strong rum punch to relax the mood, the guests-of-honour had a good time. The SX-70 Polaroids that I took show June in a chic white trouser suit, Helmut in leather waistcoat over a black shirt. In one Polaroid, Helmut is smiling broadly beside a happy-looking Sue. An amusing moment was provided by photographer John Thornton who insisted on theatrically kissing the feet of the maestro. It was a fun prelude to the lively Gallery reception the following evening.

The exhibition included images that have become defining classics in Helmut’s oeuvre, many of them reaching a considerable audience when published later that year in his first book, White Women. He was in the midst of a highly productive period, having raised his game after a near-fatal heart attack in 1971. In her promotional text for the show, Sue devised the phrase ‘imminent pornography’ to describe Helmut’s increasingly subversive determination to probe the limits of conventions and protocols in his seductive yet disquieting images.

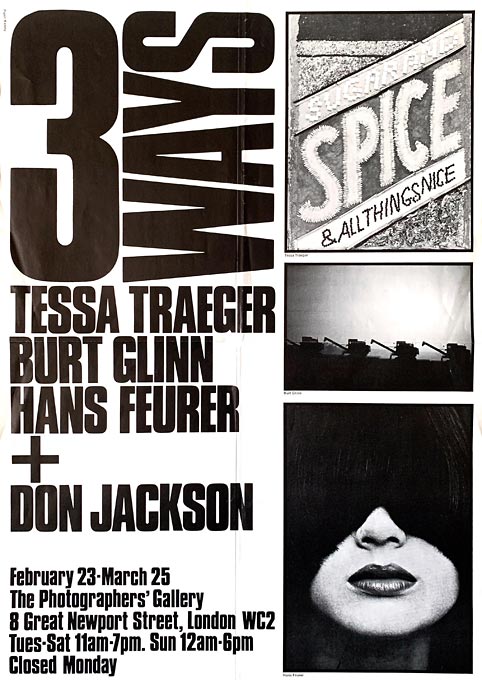

Under Sue’s leadership, the Gallery maintained a richly varied programme. I was honoured to find myself drawn in to the dialogues among Sue’s coterie of advisers, who included such diverse figures as advertising photographer Adrian Flowers, editor and cartoonist Mark Boxer, and rock guitarist Pete Townsend. This evolved – I forget the dates – into a more formal Board, as a member of which, I could observe the evolution of the Gallery from the inside. Just as I had enjoyed the years of Sue’s relative independence, so I became increasingly uncomfortable with the step changes that I witnessed towards the end of her tenure and beyond – changes driven by certain Board members and by the agendas of the Gallery’s official funders. Collector Michael Wilson and I share the distinction of having been voted off the Board for our hostility to the new politics. But I prefer to dwell on the positives and to look back on such highlights as my first opportunity to see an exhibition of work by Irving Penn (in October 1975) or a striking show of colour work by art-director-turned-photographer Hans Feurer, whose work I have long admired (in February-March 1978). I enjoyed film screenings and numerous talks. It was at The Photographers’ Gallery that I saw William Klein’s film Mr Freedom – a remarkable work, though its occasional longueurs made me aware of the hardness of the Gallery’s chairs. I recall historian and curator David Mellor’s inspired presentation of what he modestly introduced as his ’work in progress’ on the new photography in Germany in the late 1920s and early 1930s, and an engaging series of talks by three greats in the field of fashion photography, Norman Parkinson, Horst, and Terence Donovan (September 18th, 19th, and 24th 1981).

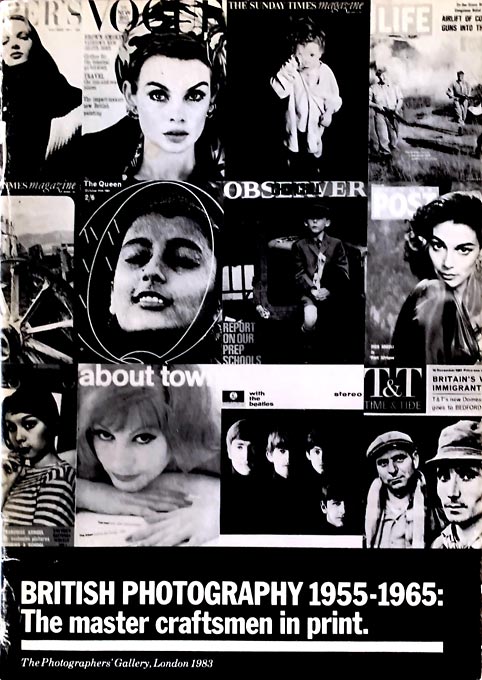

My own interest in the story of photography in print found much to appreciate in Sue’s spring 1983 exhibition ‘British Photography 1955-1965: The master craftsmen in print’. This explored photography at its crucial point of interface with its popular audience, presenting a wide-ranging selection of magazine spreads and covers as well as newspapers, books, and prints. These constituted a telling account of the breadth of talent that had vitalised the print media through the years under review. A physically slight but content-rich booklet was published to accompany the exhibition and brought together essays by key protagonists whose first-hand accounts of the behind-the-scene mechanics and dramas of the print industry remain an invaluable resource. Sue, in her Introduction, wrote: ‘Photography does not exist in a vacuum and, as well as a new generation of photographers, the late fifties produced a new generation of art directors and editors who had the means and enthusiasm to use photographs to good effect.’ With these words, and with due humility, Sue implicitly acknowledged that neither she nor The Photographers’ Gallery could claim credit as the medium’s first modern champions in Britain. But she and the Gallery did surely play an important part in the incremental growth in the 1970s and ‘80s of a more enlightened institutional response to the medium.

Another exhibition I am pleased to evoke presented a stimulatingly eclectic selection of works from the collection of Sam Wagstaff – who had bought the Penn Colette portrait in the 1975 benefit auction. Sam was arguably the most influential collector of his generation, his sophisticated, determinedly independent eye extending our appreciation of the meanings and messages that photographs might carry. His exhibition opened in November 1985, the year following the announcement that his collection had been acquired by the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles. But Sam had not lost his appetite for discovery within this endlessly engaging medium and the exhibition was drawn from his second, equally individualistic collection of 19th and 20th century works, with a few loans from the collection ceded to the Getty. I attended a tour led by Sam, who invited questions. In response to a request to identify his favourite picture in the show, he answered in a heartbeat, ‘This little colour gem by Guy Bourdin’, giving us time to admire it before adding disarmingly, ‘It’s a post card’, and explaining that it was given to him by the photographer, who declined his blank cheque for a great vintage work. This was Sam’s oblique way of debunking the conventional wisdoms around the fetish of the fine print and reminding us – as Sue had in her ‘British Photography 1955-1965: The master craftsmen in print’ exhibition – of the power and pertinence of the myriad printed forms in which we encounter photographs.

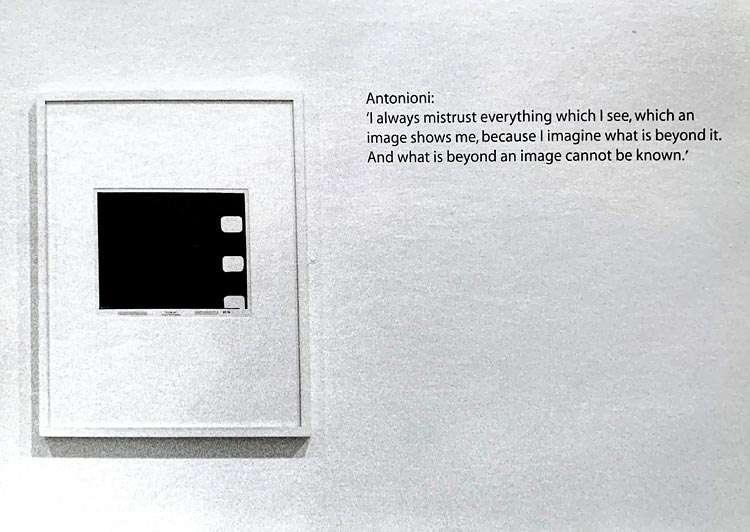

Sue’s two-decade tenure as Director was followed by that of Sue Grayson Ford from 1991 to 1994, when she was succeeded by Paul Wombell, an appointment that led the Gallery in directions that made little sense to me. The eventual appointment of Brett Rogers as Director in 2005 marked a new dawn. We had worked together before, and I was pleased to actively renew my association with her and with the Gallery when she agreed, at relatively short notice, to host an exhibition that I had developed in close collaboration with David Mellor. Our idea was to explore the theme of photography within Michelangelo Antonioni’s film Blow-Up, forty years on from its production in 1966. The exhibition’s centrepiece would be a group of the original twenty-by-twenty-four-inch blow-ups that play a central, albeit silent role in the film. These were derived from negatives supposedly made in a park by the film’s central character, a young fashion photographer, but in fact shot by Don McCullin. They would occupy the far wall in the 8 Great Newport Street gallery. Brett gave us a free hand to curate and hang the show and she fully entered into the spirit of the film with the party that followed the opening on July 19th 2006. By fortuitous coincidence, one of her Trustees, John McAslan was an architect whose practice occupied the premises that had, in the 1960s, been the studio of photographer John Cowan and became the principal set for the film. McAslan generously opened this cavernous space for the Gallery’s guests. Routemaster buses – a nod to Antonioni’s references within the film to London’s emblematic red livery – were laid on to transport us from the Gallery to the Holland Park studio. Don McCullin had visited the exhibition ahead of the crowds. The evening was attended by a number of other people involved in the film, including models Jill Kennington and Veruschka. I invited Steidl publishing director Michael Mack to the exhibition shortly before its closure. This seemed the best way to present a first draft of the sequenced images that David and I hoped to develop into a book. Michael went around the exhibition and said, ‘Let’s do it.’ The book, incorporating new research, some based on connections made through the exhibition, was published in 2010.

My connections with The Photographers’ Gallery have woven quite a number of strands of friendship and collaboration through the decades. It was a conversation with Zelda Cheatle that prompted me to set down these reminiscences, triggering the recollection of her name elegantly signed on a receipted invoice for a print by British 1930s modernist John Havinden that I bought from the Gallery in 1987, when she ran the Print Room initiated by Dorothy Bohm. I am reminded in turn of the many treasures – prints and books – I have found over the years at the Sunday table-top fairs launched by the Gallery in September 1982. The fairs’ flyers quaintly announced ‘The chance to collect at popular prices’. I last saw Sue Davies, frail but smiling, at a gathering of the faithful in 2019 on the glorious sunny July day of the unveiling of a blue plaque at 38 Porchester Terrace, the former portrait studio of distinguished 1860s society photographer Camille Silvy. Many years; many precious memories.