Some six years ago, aficionados of classic photography were made aware of a new dealership, Bazar Nadar. The man behind the intriguing name is the Belgian dealer and teacher Wouter Lambrechts. He exhibits at tabletop fairs and has a strong online presence.

I started out by asking him about his early interest in photography.

– My interest in photography began early on in my youth. My father, who was a veterinarian, had a darkroom for developing X-ray photographs. The complete darkness while loading the film, and the red light with the emerging image, felt magical to me. As a child, I frequently visited the FOMU (Antwerp Photography Museum), where I also learned about the camera obscura during a workshop. This inspired me to engage with photographic imagery.

Did you study photography? If so, where?

– Around the age of 20, I began studying photography at the KDG University College in Antwerp. It was a professional programme because I wanted to learn the techniques to work as a photographer. After my studies, I was active as a photographer of music events for about 10 years. I combined this work with teaching workshops at the Antwerp Photography Museum, the same workshops I attended as a child. Here, I discovered the joy of passing on knowledge and passion for photography to others. Through my work as a museum guide, I learned a lot about photography from the past and present – a very educational period.

Were you a collector before you became a dealer?

– I’ve been a collector all my life. As a child, I combined my interest in history with visiting museums, fairs, and flea markets. At these fairs, I discovered that it was possible to find beautiful and intriguing pieces. Of course, my budget was limited, but searching, finding, and studying items was very educational. For me, these were like “museums” where you could closely examine everything. I also discovered that building up knowledge can be very useful in recognizing the interesting items among the many available. Expertise to compensate for a limited budget.

What did you collect at that time?

– My photo collection started as a quest for didactic examples to show my photography students, focusing on the 19th century because I love primitive photography. As a photography history lecturer, I noticed that students often found that reproductions of old photos “all looked the same”. But in fact, there are numerous different techniques and processes. The viewing experience of the original object is unique. It reached a point where I had more “study material” than I could show or needed in class. Gradually, more and more photos were added to the collection, purchased for their aesthetic value instead of didactic purposes.

My personal collection is currently limited to a few historical examples used in lessons or workshops to teach about photo history, and professional literature on 19th-century photography up to the Interbellum period, to keep my expertise up to date! All other photos are for sale, making it a sort of “ever-changing” collection.

When did you become a dealer?

– When my family started wondering if I was planning to start a museum with my collection! It was also a shame that the most interesting photos were stored away in boxes. It’s much more enjoyable to find a way to share them. As a collector, I enjoyed the search and discovery of interesting images the most. As a photography history lecturer, I find the most satisfaction in reconstructing a piece of history and sharing that story with my students. With Bazar Nadar, I try to combine both passions. I’m no longer a traditional collector but search for interesting images for Bazar Nadar. This gives me the privilege of seeing many interesting and beautiful photos pass through my hands. I enjoy finding them a new, relevant home after re-contextualizing them. Meanwhile, Bazar Nadar has been around for six years, and I haven’t regretted this decision for a second.

You’re a part-time dealer and a teacher as well. Do the two roles overlap?

– My primary job is teaching, mainly theoretical subjects in the photography programme, with a focus on photo and image history. It’s very rewarding to guide young people through the fascinating story of photography. Both in the classroom and the darkroom, I share my passion for imagery with them and how people have engaged with it throughout the centuries. I especially enjoy making connections between old techniques, photographic practices, and contemporary trends. By linking a CDV album to the use of Instagram or TikTok, those antique photos become more relatable for young people. During an assignment where they researched a part of photo history through their photographic family archives, those old images began to come to life for some of them. They discover the emotions that can be associated with old images. That’s truly beautiful! It’s not just about the history of the traditional photo canon. It is not just about the history of the traditional photo canon. I am interested in the different emotions and how people used photography in the past and now.

Sometimes, new collectors are born. Once, a student proudly showed me his flea market find. He carefully pulled a meticulously stored box from his backpack. With his limited budget, he had purchased a daguerreotype! Because he found it so special during class and wanted to share this experience with his friends and family. I found that heartwarming. The combination of teaching and Bazar Nadar allows me to be deeply engaged with photographic imagery in various ways.

What kind of material do you focus on?

– For Bazar Nadar, I focus on photography that moves me. This could be because of its aesthetics, its historical narrative, or simply because it’s wonderfully bizarre and unusual. Most of the photographic material dates from the 19th century to the early 20th century. Also, the diversity of photographic processes continues to fascinate me. A key criterion is that I “fall in love” with the photo. When considering a photo, I often imagine it framed on the wall or in dialogue with other photos from the collection. If that image fits, it’s a good one! This results in a very eclectic offering.

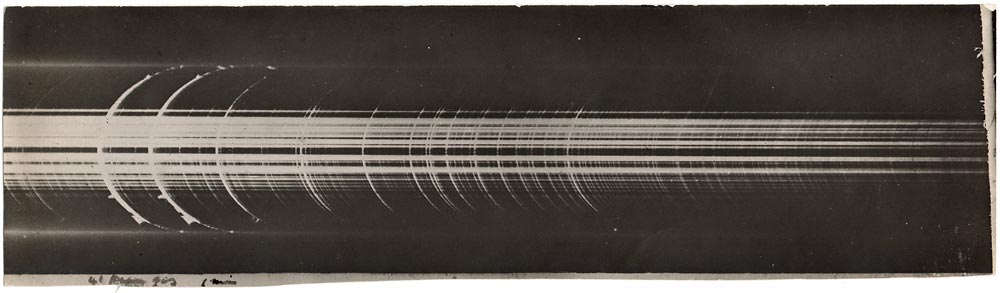

Of course, it’s nice to offer some well-known names, but systematically seeking them out is not a goal in itself. Anonymous and vernacular photos are often more surprising or moving in my opinion. There are recurring themes, though. Hands and astronomical photography fascinate me now. Or the unexpected beauty of scientific imagery.

Another favourite subject is “early copy images”. There’s nothing more interesting than finding the same image in different prints and seeing how it evolves. It often beautifully shows how people engaged with photography. The success of photography, after all, lies in its realistic and easy duplicability. In this way, stories, historical photos, and anonymous discoveries complement each other in Bazar Nadar’s offerings.

I have met you at table-top fairs, and you are active online as well. Can you tell me a little about how you operate?

– The internet is an interesting place to use as a display window. It’s also where I can provide the photos with text and explanation. People from across borders can view and discover the photos. It’s often surprising where in the world the photos end up. To give the best possible online impression, I try to create good reproductions and descriptions. But nothing beats physically studying original photos.

It’s wonderful to be able to hold and examine those old objects. That’s why fairs are also an important element, along with personal contact, of course! The internet is handy for long distances, but having a real chat with other photo enthusiasts is incredibly enjoyable. Every fair is an opportunity to make new contacts and have insightful conversations. The digital and physical aspects go hand in hand for me. They complement each other, especially for a younger audience.

These days, students gather their information via social media, not through posters or flyers anymore. Finding a new audience for old photos isn’t easy, but I believe that even a younger generation will learn to appreciate the value of photographic heritage. They will place different emphasis or collect differently than we are used to now. That’s why I actively contribute to maintaining the social media presence of the Dialogue Fair in Amsterdam, which takes various initiatives to reach a broader audience. And I appreciate that approach.

Can you discuss some works you have sold?

– Every time a photo finds a new home, I’m reassured that it’s in good hands with someone who gives it a place in a collection. This creates a new context for a photo that has already travelled a long way. A dialogue between images and stories is born again. I’m particularly proud when a museum shows interest in Bazar Nadar’s offerings. Public collections open up photo history to a broader audience, which I, as a teacher, naturally welcome. Then, the photos and stories are seen by a wider audience.

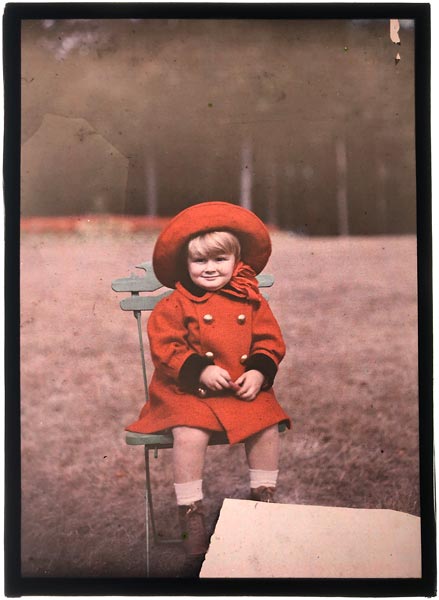

This is one of the lovely autochromes ended up at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam.

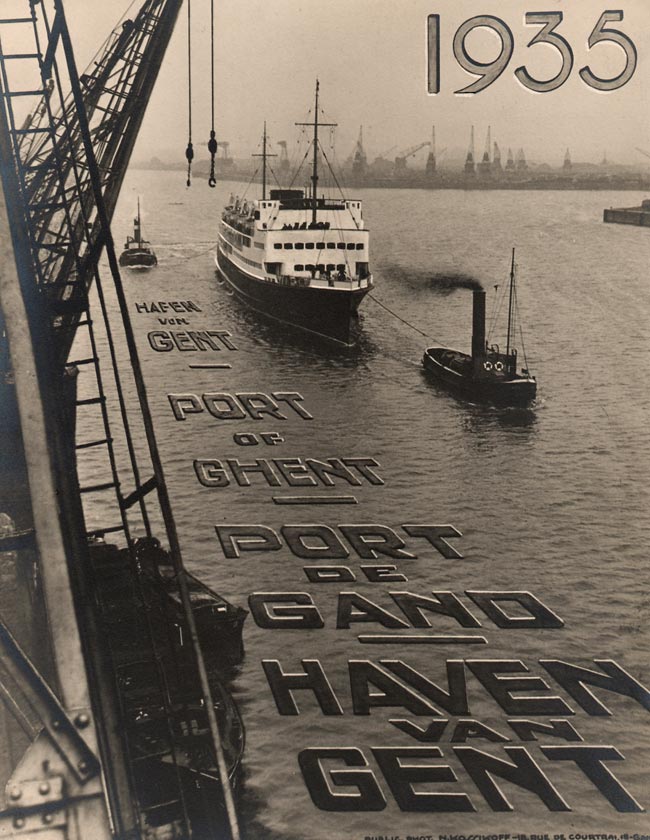

The collage by Kossikov of the Belgian port of Ghent went to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, an example of how images sometimes take unexpected and interesting paths.

I’m very proud of the two Napoleonic veterans I picked out of a large stack of photos in Paris. My photographic memory immediately recognized the style of the studio and portraits. But it wasn’t until I got home that I could further investigate whether this gut feeling was correct. The hand-coloured portraits matched the anonymous series of Napoleonic soldiers in the Anne S.K. Brown Military Collection. After much research, using a partial address and the photographer’s studio furniture, I was able to trace the maker of the photos and, therefore, the creator of the images in the Anne Brown collection. The museum was surprised and enthusiastic about this discovery and purchased the two portraits. When such puzzle pieces fall into place, it gives me a great sense of satisfaction.

– Last year, the circle was beautifully completed when the curator of the FOMU in Antwerp contacted me. They were assembling a new exhibition with the collaboration of Belgian artist Dirk Braeckman. For this exhibition, they purchased some beautiful scientific and astronomical photos that are currently on display at the museum. They are being placed in dialogue with Braeckman’s new work, creating new insights. Being able to provide photos to the museum where I, as a child, first discovered photography with wonder and where I gained so much experience as a young museum guide is truly special.

Can you share some images that you have in stock? Like the Hermann Heid?

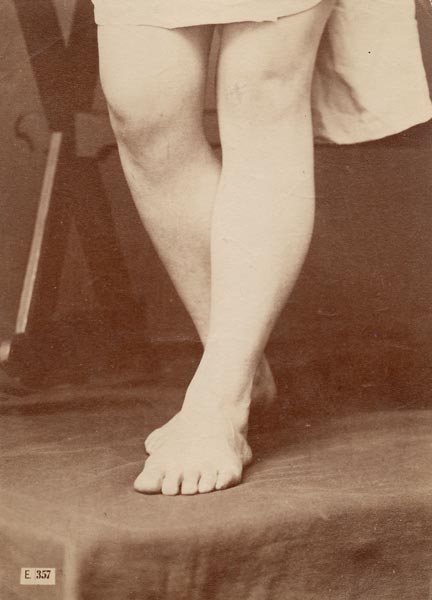

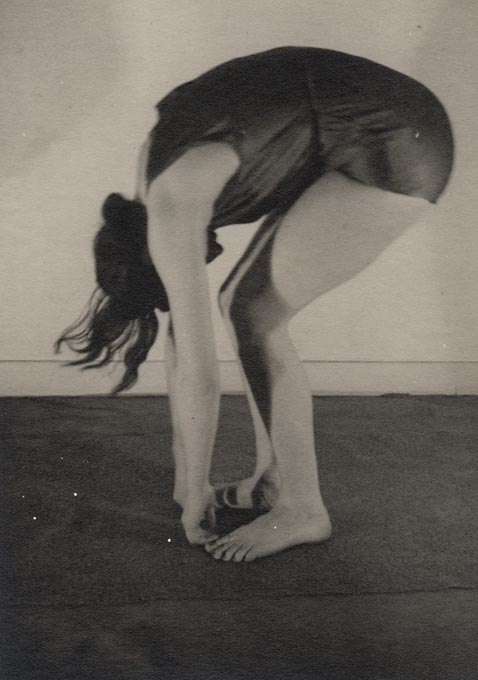

– Sure, there are a lot of artist studies made by Hermann Heid. Many of them are of rather common poses. But there exist expressive ones like this one.

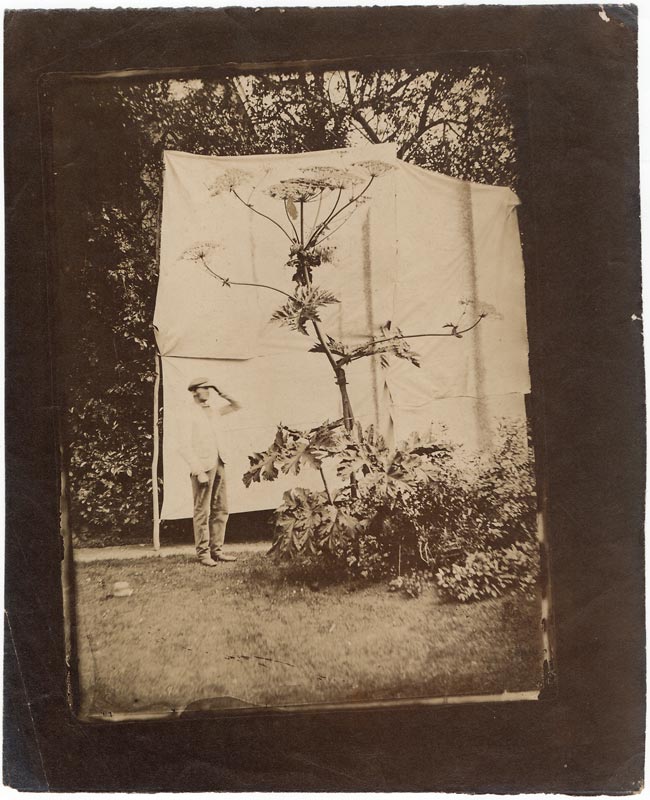

– The untrimmed albumen print is another example where you can see a part of the “making of”. I think it’s interesting to see small details like this. It teaches us how early photographers carried out their work. Looking at the man and the simple background, you suddenly realize how much work it took to make this “simple” photo of a plant. I love that!

– Interwar body culture is another topic I like because of the aesthetics combined with history. Here is an anonymous example and one by Vassil Ivanoff.

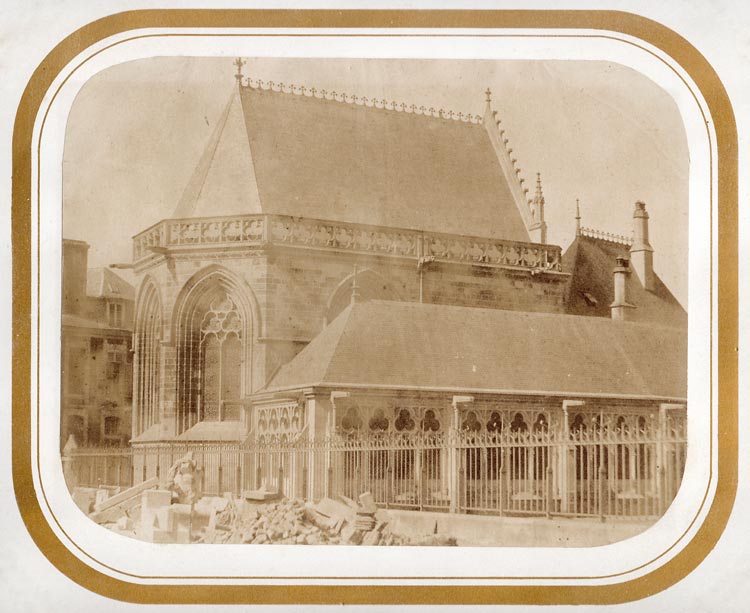

– This a large, early saltprint by Désiré Lebel. It’s an example of how beautiful primitive photography can be. The composition is balanced but has interesting and contrasting details like the pile of stones. The perfect combination of early history of the medium and an aesthetic image.

– The CDV sized image of medical students is an uncommon example of nicely staged photography in the early days of photography. They must have had much fun creating this image!

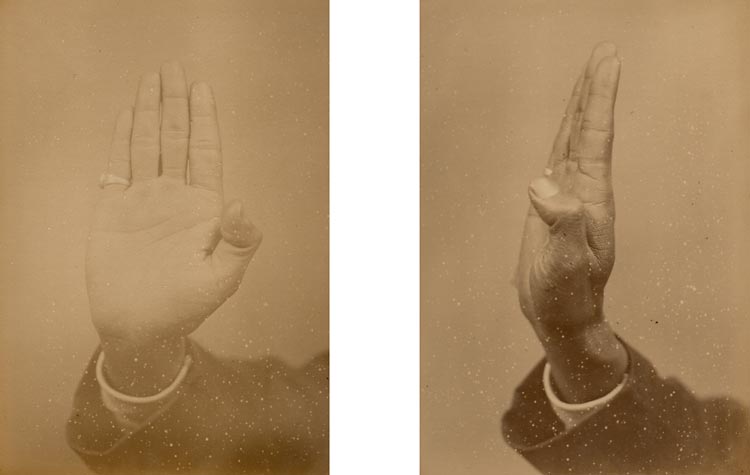

– There are quite a few images of hands in Bazar Nadar’s collection. The one with a Supraphon record on the record player is a good example of how beautiful vernacular photography can be. The other two images are examples where the aesthetics get an uncomfortable connotation because of their history. The disrespectful study of population groups in the 19th century was the reason for these photos. They were taken by Prince Roland Bonaparte for his anthropological research. It remains important to know the broader context of the photos I want to offer. Beauty is not the only part. Knowing the underlying, sometimes uncomfortable history is also an important guideline for Bazar Nadar.