Kate Hershkowitz is the daughter of renowned 19th century photography dealers Robert and Paula Hershkowitz. After a successful, 15-year-long career in the charity sector, she is joining Robert Hershkowitz Ltd. and taking the business forward.

You grew up surrounded by 19th century photography. As a child, did you take any interest in it?

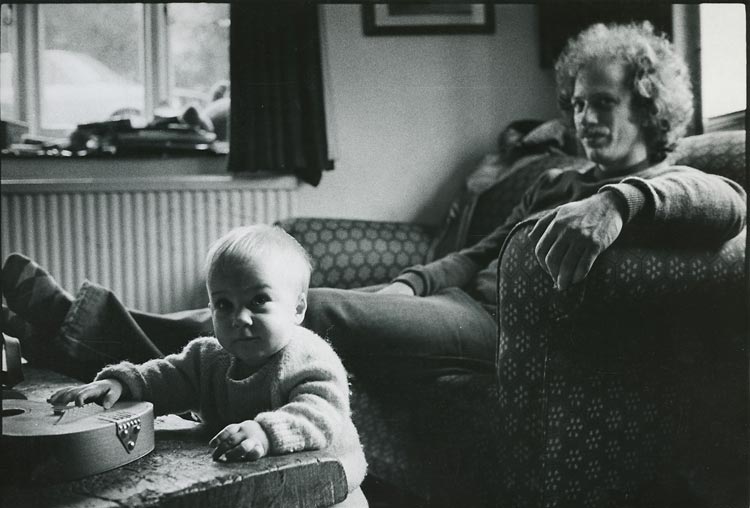

– My earliest memories of 19th century photography are not of the photographs themselves, rather of the dealers and collectors. I remember in the mid-80’s the American dealers; Hans Kraus, Mack Lee, Willie Schaeffer and Chuck Isaacs, mostly sporting moustaches arriving at my parents’ house during “auction week”, when Sotheby’s and Christie’s held morning and afternoon photography sales three times a year. And the reverberating voice of Harry Lunn, an imposing figure to an eight-year-old, was invariably present. We holidayed in France with Joachim Bonnemaison and Alain Paviot, and their families, and visited Jay McDonald in Santa Monica. Our walls were decorated not only with P. H. Emersons (because of their being more resilient to UV light) but also Hershkowitz family portraits by Willem Diepraam, Chuck Isaacs, Marianna Cook, Richard Menschel’s wife, Ronay, and Michael Wilson – all forming part of my introduction to photography. If I were to choose an early influence from the 19th century, it would be Emerson. I liked the delicate, graphic photogravures, from Marsh Leaves particularly, and the platinum print portraits depicting agrarian life, with his famous Gathering Waterlilies, hung above my parents’ bed.

Early on, what career did you map out for yourself?

– I inherited my parents’ love of travel and spent five months after school volunteering in Uganda on an environmental project. I was keen to pursue a career in international development or conservation, initially working for Defra as my first job out of university. I then moved to the charity sector, where I worked for 15 years mostly in fundraising and events.

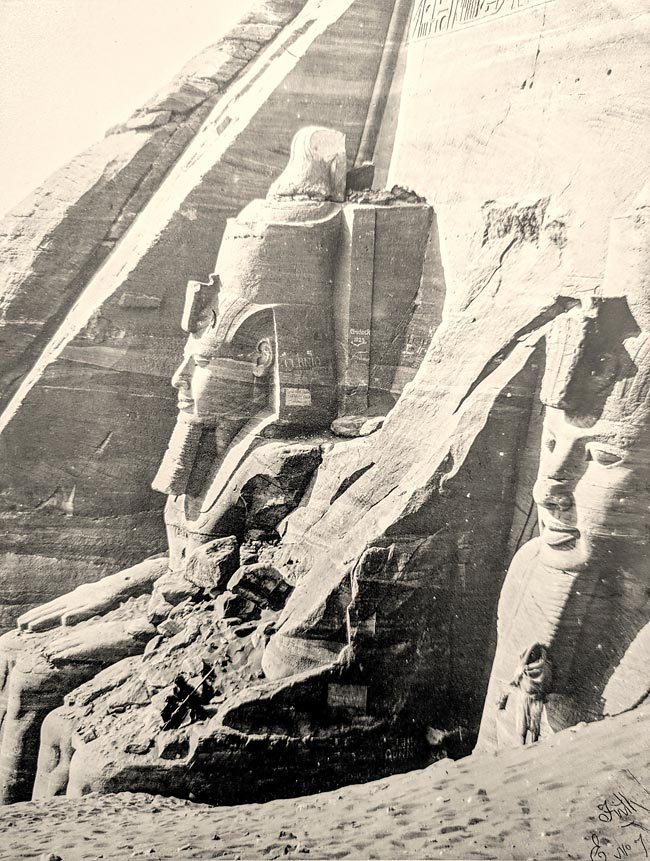

I suppose it’s no surprise then that other 19th century photographs I responded to early on were from expeditions by Frith and Bourne. From the desert and monuments in Frith’s images to the towering Himalayas captured by Bourne, I was somewhat in awe – particularly when you consider the challenges of transporting boxes of chemicals, glass plates and portable darkrooms on the backs of camels or over mountain passes at 18 000 feet. I always had a feeling for early travel photography and hoped I would find myself working with these and similar exploratory images eventually.

You have assisted at fairs and attended auctions with your parents. When and why did you decide to join the business?

– I enjoyed the opportunity to work with my parents at Paris Photo and Photo London, visit other dealers and clients, and attend auctions, also accompanying Dad to New York in 2006 as his “PA” after he broke his hip. I like the buzz of the fairs, seeing familiar faces and meeting new people. A turning point came when I found I could talk about the photographs we were exhibiting with confidence and, despite this not being my day job, had already absorbed a great deal.

During Covid, I spent some time with my father going through our inventory, cataloguing over 1200 images. It led to a much more in-depth understanding of the material, but also the importance of the informative anecdotes that accompany them. For example, he pointed out to me what Sam Wagstaff had previously pointed out to him, that Emerson’s The Last Gate, the final image in his final book, Marsh Leaves, was in fact the left half of The Wealth of Marshland from Idylls of the Norfolk Broad, Emerson’s first photogravure publication. My dad always considered Marsh Leaves to be the single most beautiful 19th century photographically illustrated book. A deluxe edition of this inscribed on the inside cover by Emerson was one of the first things I bought at auction when I decided to start my own small vintage photography business. These experiences crystallised how much I enjoyed working with this material, and how valuable it was, in all senses, to spend time with my parents and absorb as much as possible.

Was it a big decision to change careers?

– Whilst I was leaving a career where I managed a team of fundraisers at the NSPCC, something I always enjoyed, I was ready for a change. And I knew that although dad was proud of what I’d achieved, what would give him profound pleasure would be my continuing his life’s work and that my feeling for and understanding of 19th century photography would grow.

I also found, through buying my own material, that I really enjoyed discovering about the photographers and their subject matters. For example, I learned that Abu Simbel was moved in 1968 as part of the International Campaign to Save the Monuments of Nubia in order to accommodate the building of the Aswan Dam. This therefore makes Frith’s striking images even more special as they also serve as a historic record of these relics taken in their original location, further elevating the value of early photography.

I could also bring some practical benefits to my parents. Having used “technology” throughout my working life, there are things that are second nature to me that my father, stuck happily in the age of paper, seems wilfully unable to learn. And though my mother is surprisingly strong and extremely determined, it helps to have someone a generation younger to move photos in and out of plan chests, wrap packages, hang frames, transport luggage, and so on.

Your father is known throughout the photography world for his extraordinary eye. What are the most important lessons you have learnt from him?

– The main lesson is to spend a long time looking – and after “hard looking” to finally see, which can be a time-consuming process. Through this approach, he has developed his exceptional eye. He also encourages me to trust my own eye – something he was taught by his mentors Clifford Ackley, then curator at the Boston Museum, and Sam Wagstaff. He has an amazing memory for photographs, able to recall how a photograph was acquired even forty years earlier and, in particular, how he felt about it at that time – recognising that how you feel about a photograph helps cement your memory of it.

He has taught me that learning never stops. He is delighted when somebody points out something he hadn’t seen before in one of his own photographs – for example, the man seated in front of Howlett’s Great Eastern, highlighted to him by my mother.

And finally, if you make a mistake, which everyone does, you will learn from it and not to give yourself a hard time about it, a lesson that was reiterated by Serge Kakou after I bid in my first French auction (which was not necessarily a comment on my purchase!).

Some collectors and dealers prefer French or British photography. Do you have a preference? If so, why?

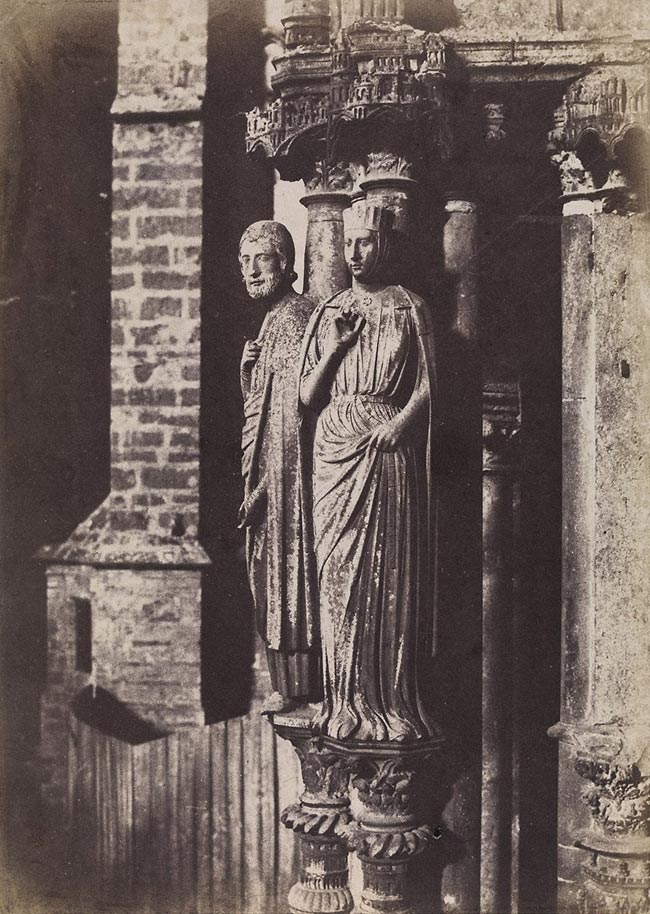

– It’s too early for me to have a preference. The volume of work in early French photography is so much greater, with more notable photographers in the French pantheon, and commercial printers like Blanquart-Évrard and Fonteny presenting additional variations in texture and tone. However, contributors to early British photography like Fox Talbot, Linnaeus Tripe, Roger Fenton, Charles Clifford and Henry White are among my favourites, so I suppose the answer would be that there are too many wonderful examples within both French and British photography that I couldn’t choose – I simply appreciate the richness and diversity they have to offer.

This spring, your father presented a beautiful exhibition of French paper negative photography at Photo London. He selected the material but he left the sequencing and hanging to you. How did you work it all out?

– Because it was an exhibition so personal to him, I tried to extract the story he was wanting to tell by showing each photograph. Did we want to hang together three photographs by Baldus to show the variation in the look (soft, hard or sharp) of a paper negative photograph by the same photographer? Or in other areas, were there particular themes he wanted to highlight? In the end, some naturally grouped together, for example, a wall of’early photographs (positive and negative pairs by Charles Nègre and Humbert de Molard), to demonstrate development within photography’s early years. Similarly, there were photographs printed by Blanquart-Évrard who published work by relatively unknown photographers as well as known masters, which produced a decidedly black and white look. One consideration, learned from my mother, was to be careful not to place very strong prints next to more delicate ones, so as not to detract from one another. And I learned a lot from Mathilde at Photo London about how to cluster photographs for maximum impact. And, of course, there were a couple of last-minute changes during the hanging of the show upon seeing each grouping in situ.

How do you see the business moving forward? Do you plan to show at the international fairs? Paris Photo for instance? Your father is not keen on the digital world. Do you have plans for expanding the business in it?

– In time for Photo London this year, I set up our first website – www.hershkowitzgallery.com and Instagram will follow. We will probably continue to exhibit at Photo London, and this year I will personally be taking tables for the first time at 24.39, the classic photography fair at Pavilion Wagram on 9th November. The plan is to continue Robert Hershkowitz Ltd, as well as develop my own business within, which will include material in which my father hasn’t been prominent, such as vernacular photography, cased images and some modern and contemporary. And I will continue to collect examples of early travel photography – ethnographic portraits and historic sites of cultural interest. I’m already looking forward to 2039, celebrating with fellow enthusiasts the 200th anniversary of the introduction of photography to the public.