This article is an appendix to the article Photography at La Salpêtrière and beyond, published in issue 6 of The Classic, available as a pdf on our website.

As discussed in the article in the magazine, the photography that was carried out carried by Duchenne de Boulogne, Paul Regnard and Albert Londe under the auspices of Jean-Martin Charcot at La Salpêtrière, would have a considerable influence on the arts. Duchenne lectured at L’École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts for many years, and hysteria, the disorder that made Charcot a household name in France, was described by novelist and playwrightJules Claretie as “the illness of our age”, and became a common theme in literature and drama. Actresses, including Sarah Bernhardt, would come to the public demonstrations of Blanche Wittmann, “The Queen of The Hysterics”, to study her when they were given roles as hysterics. The latter would also be the focal point of André Brouillet’s painting, A Clinical Lesson at La Salpêtrière, 1886 – 1887, after Rembrandt’s The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp (1632), one of the most famous medical paintings in art history.

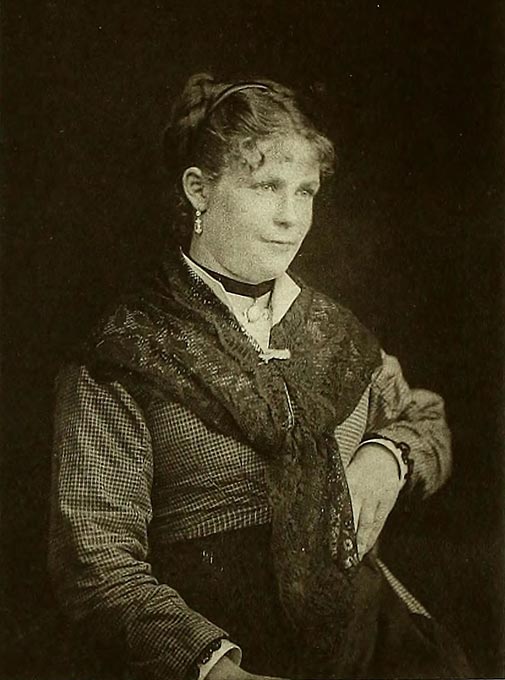

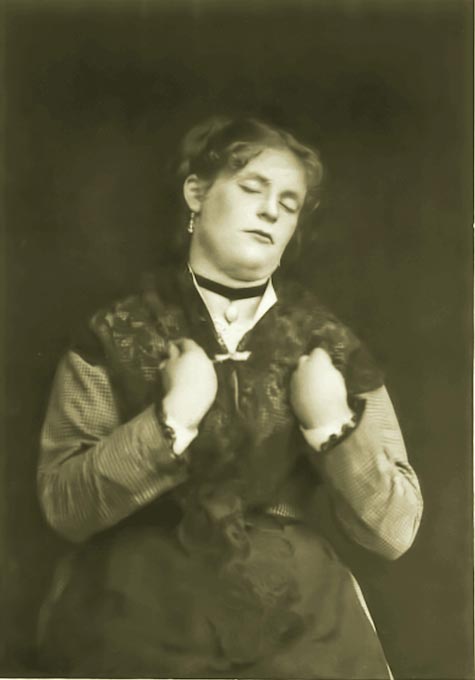

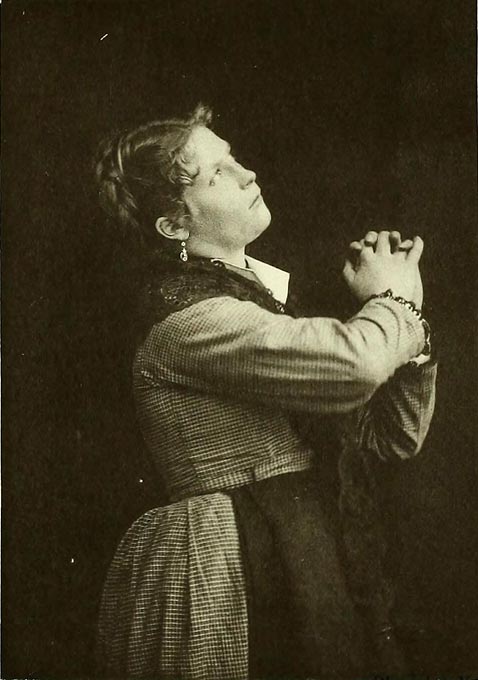

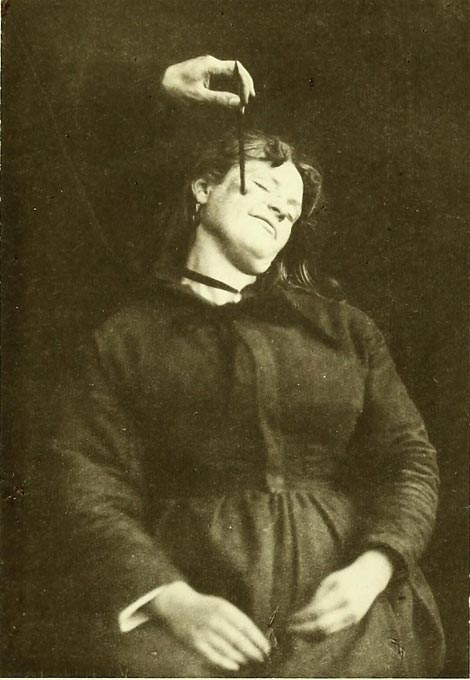

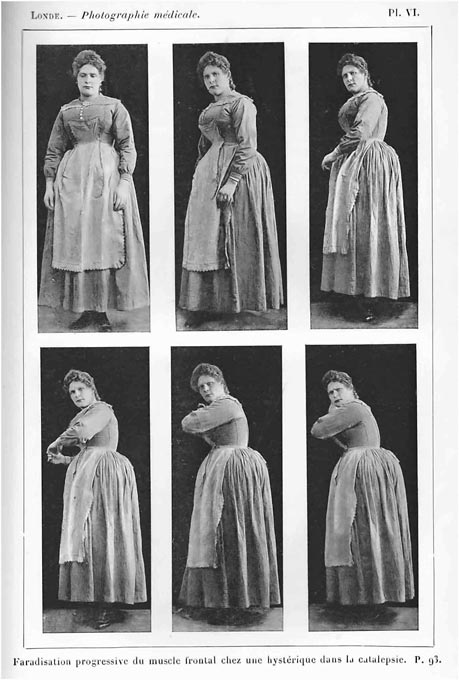

The demonstrations at La Salpêtrière were a kind of performance, dramatically lit, where Charcot, his assistants and Wittmann would enter in silence, before Charcot would hypnotise her. Wittmann became “The Queen of the Hysterics” partly because she was entirely predictable during the three hypnotic stages as defined by Charcot, Catalepsy, Lethargy and Somnambulism, partly because of her acting abilities, demonstrated in the third stage, Somnambulism, also called “the suggestible state”, where Wittmann would act in whatever scenarios she was given, by Charcot, or at his invitation, by members of the audience, such as being surrounded by rats or snakes, to act as donkey or a finely dressed lady of the upper class.

But the links to the arts were also strong within the hospital itself, thanks to Charcot, whom after his death was described by Sigmund Freud as having had “the nature of an artist”, that he was not a thinker but “a visuel, a man who sees.” And his interest in all things visual led to there being depictions of hysteria and other disorders all over the hospital, wax and plaster models in the hospital museum, drawings and photographs in rooms and corridors. As far as the arts were concerned, Charcot’s interest was also retroactive. He and Paul Richer published several books, including Les Démoniaques dans l’Art and l’Hysterie dans l’Art, where they would analyse historical paintings and artworks showing religious ecstasy and demonic possessions, looking for symptoms, diagnosing the figures according to Charcot’s theory of hysteria.

While Egon Schiele and the Surrealists would use the legacy of Charcot and the photographs that were taken during his reign at La Salpêtrière for their own ends, the interpretations of that reign that have emerged in the arts during the last 40 years have been far more direct and critical of Charcot, including artist Mary Kelly’s Interim (1984 – 1989), choreographer Narelle Bejamin’s I Dream of Augustine (2004) and recently, Mousework (2020), by Izit Azoulay. Much of it has focused on individual patients at La Salpêtrière, Augustine Gleizes, these days sometimes referred to as “Paul Regard’s Supermodel”, and Blanche Wittmann.

The more recent interpretations of Charcot’s reign in the arts have done much to shape how it is viewed, even to the point of rewriting history and establishing fictions. None more so than Swedish author Per Olov Enquist’s 2006 novel The Story of Blanche and Marie, Marie being Marie Curie. The novel is largely told in feverish flashbacks, where Wittmann becomes Charcot’s lover, and helps Curie in the discovery of Radium. The novel was published to considerable international acclaim and was praised by reviewers for its feminist perspective and its historical accuracy.

But the novel is a work of the imagination. Curie didn’t work at La Salpêtrière and there is no evidence that she ever met Wittmann. Enquist states that Wittmann died in 1913, whereas in fact, she died in 1909. He quotes from Wittmann’s poetry, scribbled in three notebooks, but neither poetry nor notebooks are known to have existed. Likewise there is no evidence of any “lovers relationship” with Charcot. And what all reviewers picked up on was Enquist’s description of Wittmann’s physical condition in her final years. Her body had indeed been damaged by exposure to radiation, but not through any scientific research with Curie on Radium but through her work as an assistant at the x-ray department at La Salpêtrière, first under Albert Londe, then Charles Infroit. In Enquist’s novel she is described as a head with a trunk, with one remaining arm for writing, and for wheeling herself around in the wooden box on wheels that had been made for her.

One such review, written by a Terry Eagleton, a professor of literature, made its made way into British medical journal The Lancet, prompting anangry rebuke from Professor Jan van Gijn, professor of Neurology at the university hospital in Utrecht, who clarified the facts of Wittmann’s physical condition, that she had ” lost fingers, then parts of her arms but her legs were unaffected”, and van Rijn added that that Enquist’s description “strikes me as bad taste”. An angry letter in The Lancet seems to have had little effect. The fictions in the novel have been accepted as facts in many quarters, even by some medical historians, and they have by now attached themselves to Wittmann’s memory, Brouillet’s painting and Regnard’s and Londe’s photographs of her.

While Charcot and the doctors under him wrote extensively about their hysterical patients, rarely are the patients’ own voices heard. But in 1905, 12 years after Charcot’s death, Alphonse Baudouin (1876 – 1956) entered La Salpêtrière as an intern, and recounted his experiences in his 1925 memoir, Quelques Souvenirs de La Salpêtrière. With Charcot’s theory on hysteria in tatters, he comments, “one didn’t talk much about hysteria”. But Blanche Wittmann intrigued him. She had after all been “The Queen of the Hysterics”. She could still be moody, changeable he writes, but this did not affect her work in the x-ray department and she no longer had hysterical attacks. Baudouin writes, “Like all the hysterics from La Belle Époque, she seemed to deny her past, and when questioned about the slightest details of that part of her life, she responded with a refusal tinged with anger”, adding, “She was also one of the early victims of radiation-induced cancer, a disease that ravaged the pioneers of this new discipline, causing them to lose limbs. She stoically endured the last agonising days of life.”

Still, Baudouin was curious about Charcot and what had actually gone on at the hospital. He quotes from a conversation he had with her. “Listen, Blanche. I know there are things you don’t want to talk about, but you’ve known me for a long time and you know that I have no intention to make fun of you. I’d like you to explain something about the attacks you used to have.” After hesitating a moment, she replied: “Well! What do you want to know? They claim that all these attacks were faked, that the patients pretended to be asleep and that the whole thing was a joke on the doctors. What’s the truth in all that? None of it’s true. It’s all lies; if we fell asleep, if we had attacks, it was because we were helpless to do otherwise. What’s more, it was very unpleasant”. And she added: “Fakery! Do you think it would have been easy to fool Monsieur Charcot? Yes, there were tricksters who tried; he simply gave them a look that said: ‘Be still’.

There has been much speculation about what ailed the hysterics over the years, conversion disorder being the most immediate candidate for the most group of hysterical symptoms. It usually emerges suddenly after a period of emotional or physical distress or psychological conflicts, with symptoms including blindness, weakness, paralysis, abnormal movements, non-epileptic seizures with loss of consciousness. Medical historians who have studied the case notes have suggested other diagnoses for some of the patients at La Salpêtrière including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, epilepsy, PTSD, multiple personality disorder and that these would have been exacerbated by their life experiences before and at La Salpêtrière.

In 2016, S. Giménez-Roldán, former head of the Department of Neurology Hospital General General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, presented a paper titled Clinical History of Blanche Wittmann and current knowledge of psychogenic non-epilectic seizures, where Wittmann’s hysterical attacks as reported by Bourneville and Regnard were compared to psychogenic non-epileptic seizures (PNES), presenting these results and the conclusions.

Results. According to recent studies, B.W.’s hysterical attacks share numerous features with PNES, including their long duration, presence of repetitive oscillatory body movements during episodes, a history of childhood abuse, and attraction to certain objects. Charcot used hysterical patients’ susceptibility to hypnosis as a tool to distinguish hysterical attacks from epileptic seizures; hypnosis has in fact been found to be no different from placebo in some video-EEG laboratories. However, certain features, such as ovarian hypersensitivity and displaying theatrical poses (attitudes passionnelles) at the end of an attack of grande hystérie, were rather peculiar and were probably connected with the atmosphere at La Salpêtrière and Charcot’s authoritarian personality. Charcot’s hypothesis that episodes were caused by ‘functional lesions’ is concordant with findings from functional MRI.

Conclusions. The case of B.W. provides valuable information for understanding some phenomena associated with hysteria.