This is an appendix to the interview with Jerry McMillan in the article “Busting Out of Straight Photography in the 1960s and 70s”, published in issue 7 of The Classic. In the late 1950s, McMillan and four friends; Ed Ruscha, Patrick Blackwell, Don Moore and Jo Goode, decided to leave Oklahoma City, and go to art school, the Chouinard Art Institute in Los Angeles. They shared a house in Hollywood, where Patrick Blackwell would interest the others in photography. McMillan was, by his own admission, “not that great a painter and I loved that photography was so much faster than doing painting. In 1961, I took a group portrait for the invite to War Babies, the inaugural show at Huysman Gallery in LA.” The artists, Ed Bereal, Jo Goode, Ron Miyashiro and Larry Bell, were all of different ethnic backgrounds. “The idea was that they were going to sit at a table and eat food related to that, with the Stars and Stripes as table cloth.”

The invite, and the individual portraits McMillan took of the four, which were also included in the exhibition, got a lot of attention and were as McMillan says, “my introduction to the art and photography scene.”

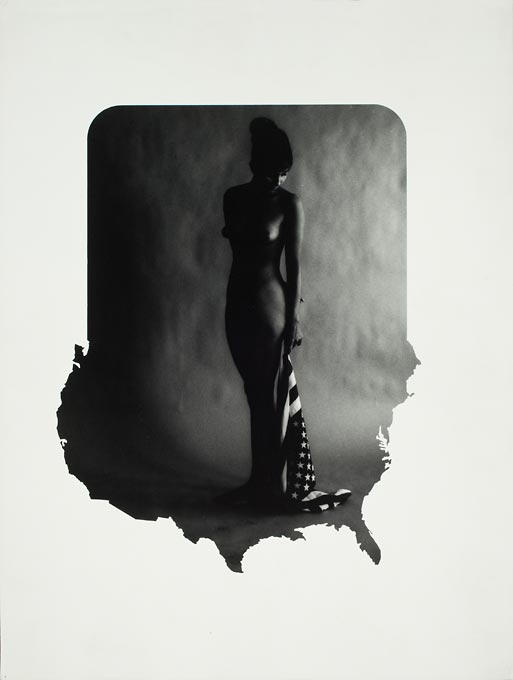

McMillan would go on to photograph most of the leading names on the Los Angeles art scene, alongside working on his own projects. In 1962, he produced his series Flag, reusing the Stars and Stripes he had bought for the War Babies shoot.

A year later, he produced the series Jan.

– The Civil Rights Movement was going on at that time. A lot of photographers were documenting that but that kind of photography didn’t interest me. I wanted to do something different so I did a series with a black model called Jan, making collages, photographing photographs of her etc.

But McMillan was determined to push the envelope further. Starting with Patty as a Container (1963), photographs of his pregnant wife, made into a box.

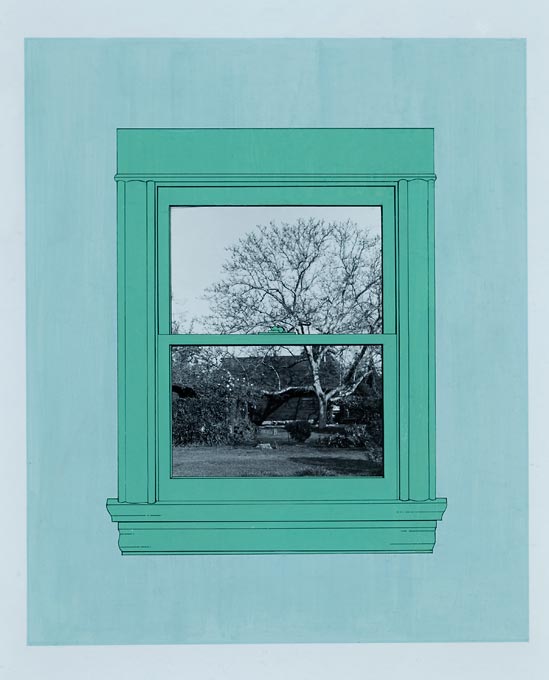

– When I was in art school, a big influence on me, was Robert Irwin, and he dealt a lot with spatial ideas. We would discuss Abstract Expressionist painters and applied spatial ideas in painting. And spatial ideas would become the most important in my work. I did two series, Door #1 and Window #2, where I had a very flat, painted space in combination with the illusionistic space of photography.

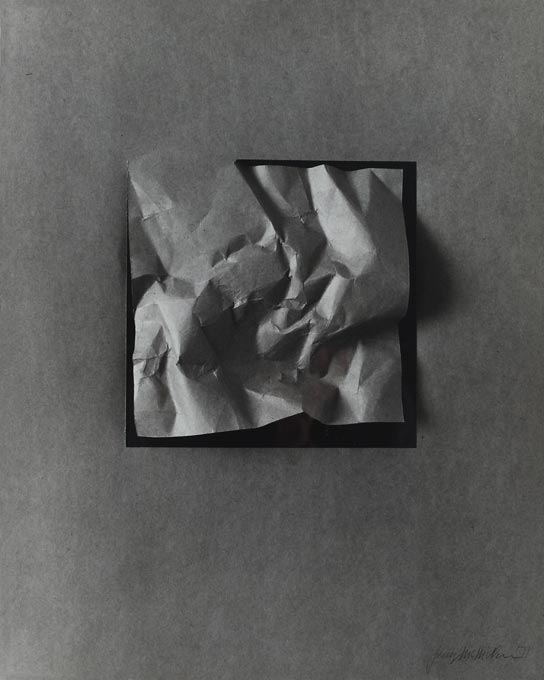

These ideas would lead McMillan towards his famous Bag series, one of the first being a photograph of wrinkled brown paper, the print, “straight as whistle, turned into a bag.

McMillan had several works in the 1970 MoMA exhibition Photography Into Sculpture, curated by Peter C. Bunnell. A further development came when McMillan was asked to contribute to the portfolio The Silver See (1977), sold to raise funds for the Center of Photographic Studies.

– That really changed things for me. At the time, I was doing metal pieces and photographic pieces. When I was asked to contribute, I had a year to think about what I was going to do. I asked myself, “What’s the difference between photography and art?” The real difference is that art has non-objective abstraction in its history. Photography doesn’t. Could a photographer do a non-objective abstract work, and I don’t mean a picture of peeling paint on a wall. That just looks like abstraction but it isn’t. I thought, what does photography do? It represents three-dimensional space, on a two-dimensional plane. And that was how I began addressing my work, using the camera as a mechanical, spatial tool. The first piece I did was a square, made from brown paper, with a middle tone, I cut a square, except for one corner, and then I had a non-objective, geometric square. I then decided to make a change, I wrinkled the square up, so it looked like a drying leaf, thereby adding dimension, instead of being flat. Then that was put straight in front of a camera, adding photographic space, to that already spatial idea.

I made 45 prints of it for the portfolio, and it stunned the photo community. I said, “What I’m trying to show you is that there’s another way to think, it allows me to change the visual vocabulary of photography. You don’t realise you’re looking at a photograph. Because photographic space is invisible space. You don’t see it. You see the first two steps and you don’t realise there’s a third step.”

The work got a lot of attention. But so did the many portraits McMillan took of the Los Angeles art scene. McMillan comments,

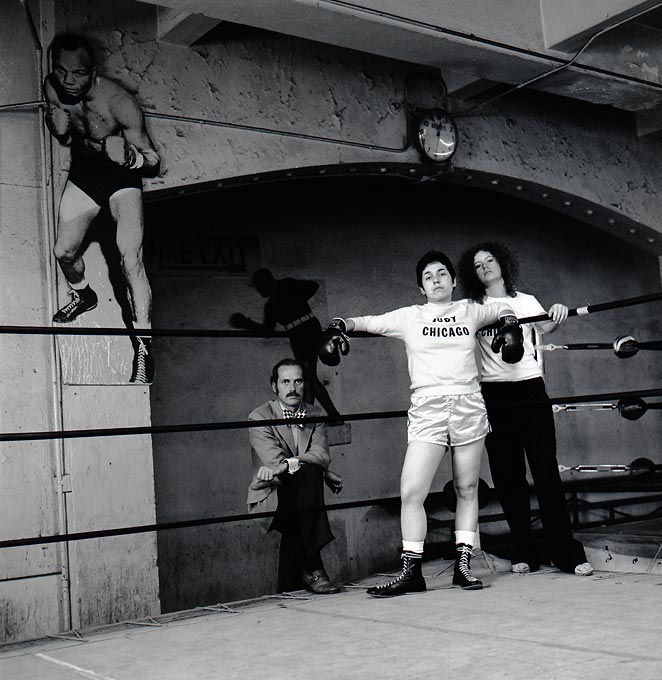

Judy Chicago, 1970

– Judy had a tough mouth! She was like a sailor who had just come back from a long voyage! But she had a good sense of humour and was very outspoken, particularly about women artists. Her dealer, Jack Glenn, was putting together a show of her work at Faculty Club, California State University Fullerton, and asked if I could shoot something for it? I thought about it. I had photographed her before, when she was still known as Judy Gerowitz. And we had shown at the same gallery and she was best friends with Jan who had modelled for my Jan series. I went to a deli to have coffee with Ed Ruscha and Joe Goode, and we talked about Judy being a fighter. Almost as joke I said, “Maybe I should photograph her as a boxer!” But the idea stuck. Judy and Jack liked the idea. I went to the Main Street Gym, which was the boxinggym in Los Angeles. I had a hard time convincing the owner that what we were going to do wasn’t make a lot of money but the money he asked for was a lot and he wanted it in cash. The other woman in the picture I didn’t know. She was a girlfriend of another artist. The owner informed us that we only had minutes to shoot so we had to be quick. Jack had been in dialogue with Artforum and when he sent the invite with the picture on it, they liked it so much that they copied the picture and did three pages on Judy in the magazine. And instantly, Judy got international exposure. And that was the first time she used the name Judy Chicago.

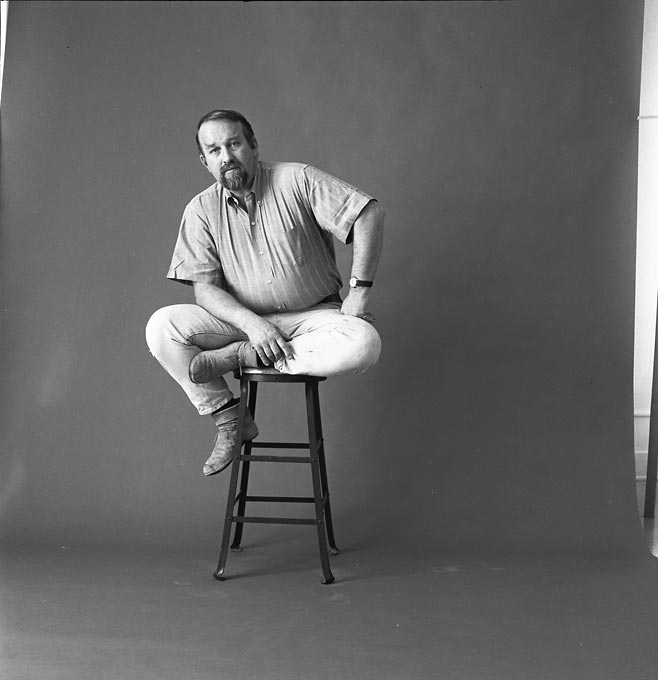

Craig Kauffman, 1968.

– This was shot for the LA 6 exhibition. It was an exhibition of six Los Angeles artists, curated by John Coplans, all new work by them and it was going to Vancouver. I was asked to design the catalogue. When I started designing, I decided to take portraits for it myself instead of asking the artists to supply them, so that the portraits would as current as the work. I invited them individually to my studio. This was part of a trend I started. Jo Goode was about to do a show at Nicolas Wilder Gallery and Craig asked me if I could do something for the invite. I said sure. I thought about it and I said, “People usually choose the work they like best. Why don’t I shoot an Irving Penn-like portrait of you?” It didn’t even have his name on it and everybody talked about it! So suddenly all the artists wanted me to shoot portraits of them, including Craig Kauffman and the others in the LA 6 exhibition. Life magazine asked me to shoot some portraits as well around that time but they never used them. The attitude at Life was, “Who cares about LA art?” It was all about New York back then in the early and mid-60s.

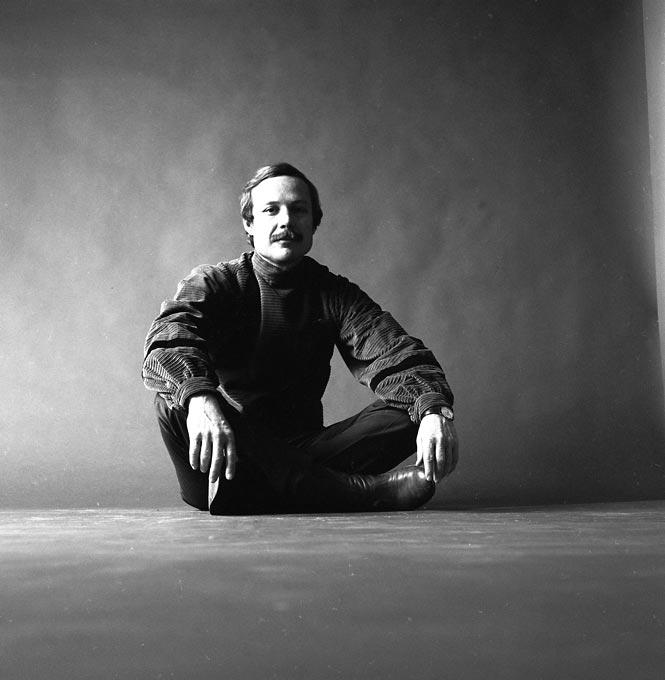

Bob Irwin, 1968

– As I said earlier, Bob Irwin was a great influence on me and he was also part of the LA 6 exhibition. John Coplans was absolutely crazy about the photographs and he said, “I’m going to have those blown up and put them in the show!” He took charge of that so I actually never saw the blow ups myself. The crates with the work came back to Los Angeles and I asked Coplans about the blow ups, I mean they were my work. But he said, “I can’t give them to you because we sold them to a collector in Vancouver.” I wasn’t told and I wasn’t paid. I couldn’t believe it! But that was John Coplans for you! I did a few exhibition catalogues for him but he was always a nightmare.

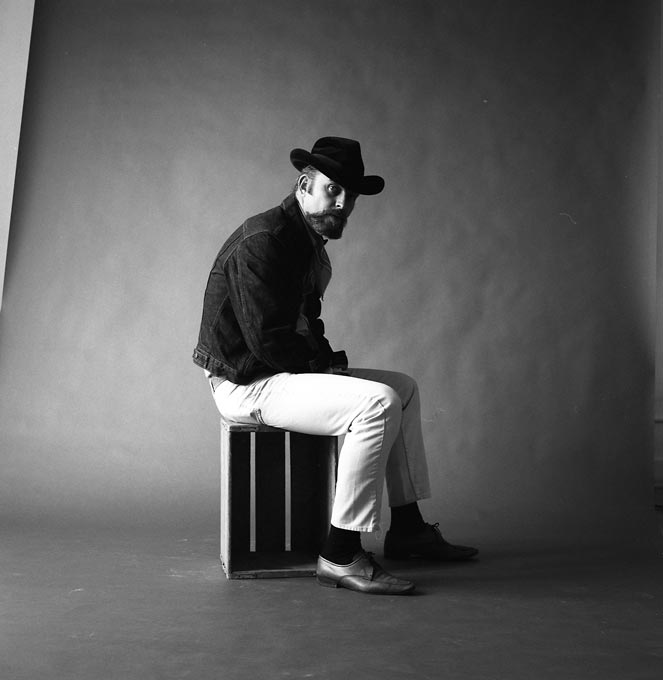

Ed Kienholz, 1968

– Again, part of the LA6. The thing about those portraits, I didn’t direct them. I had put the stool out for Ed as something to sit on while I was setting up and he just climbed up on it and the shot was there. Ed was doing really interesting stuff and he wanted to trade some doors and door handles in my studio but I couldn’t do that of course as I didn’t own the space, I was renting it.

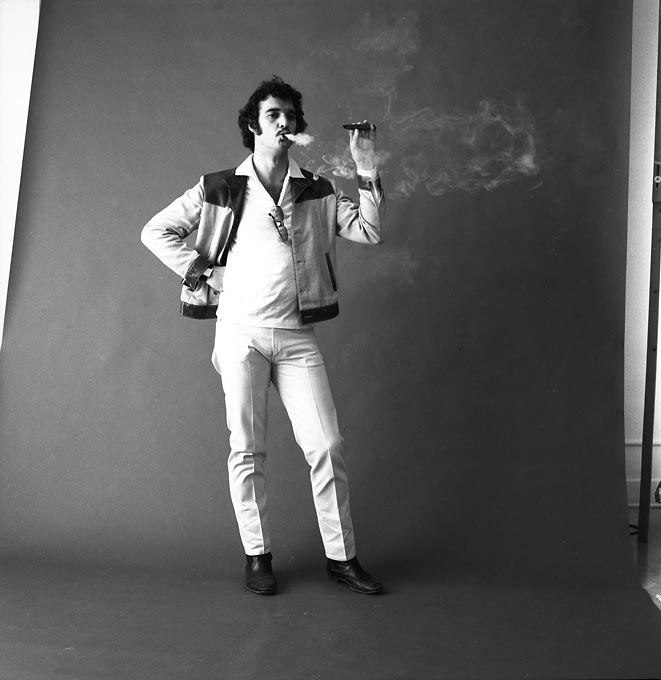

Larry Bell, 1968

– Same shoot, LA 6, again, no directions, Larry turned up, lit a cigar, and I shot. We knew each other well as we had gone to Chouinard Art Institute together. And Larry had been part of the War Babies exhibition that I had shot the invite and portraits for.

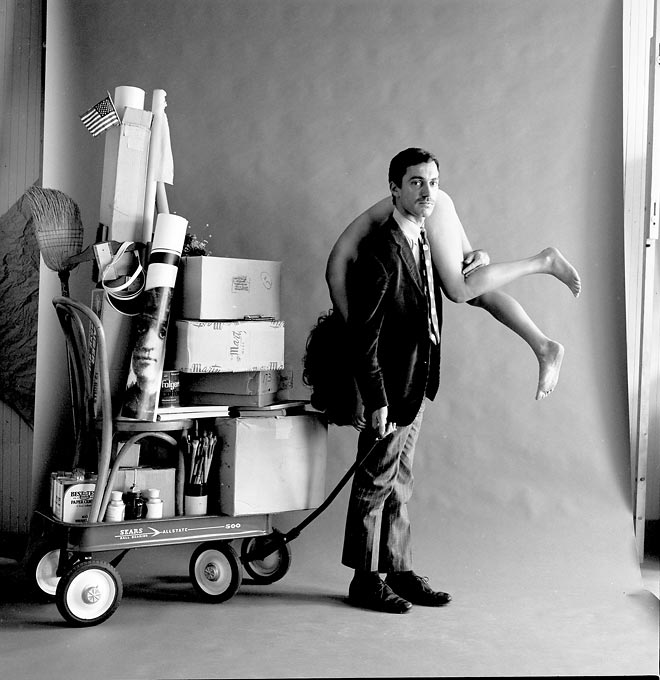

Charles E White III (moving his studio), 1965

– Charlie was an artist and we were good friends but at the time I took that photograph, he was primarily a commercial illustrator, in fact, the top commercial illustrator in Los Angeles. He won some 20 awards from the Art Director Club which was simply unheard of. He was about to move his studio so we moved all his stuff to my studio to use for the shoot but the cart belonged to my young son. The model in the picture had done some work for Charlie but was about to return to her job in New York. Charlie looks very casual but he must have picked her up 50 times before we got it right. He sent the picture to everybody in the advertising world and you would see it in every other office you walked into.

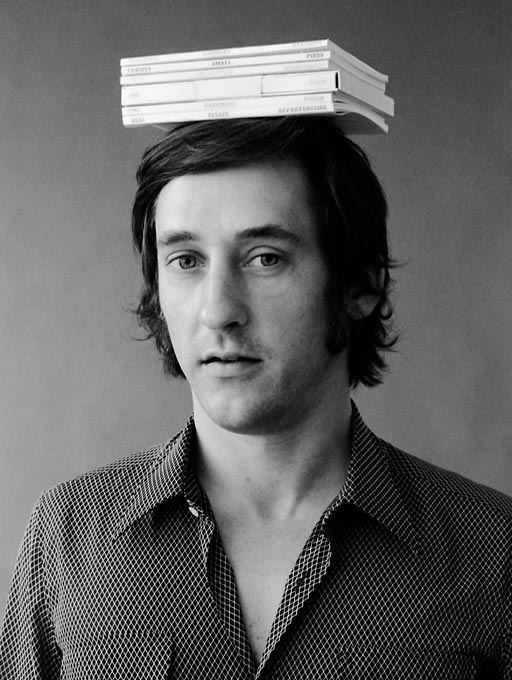

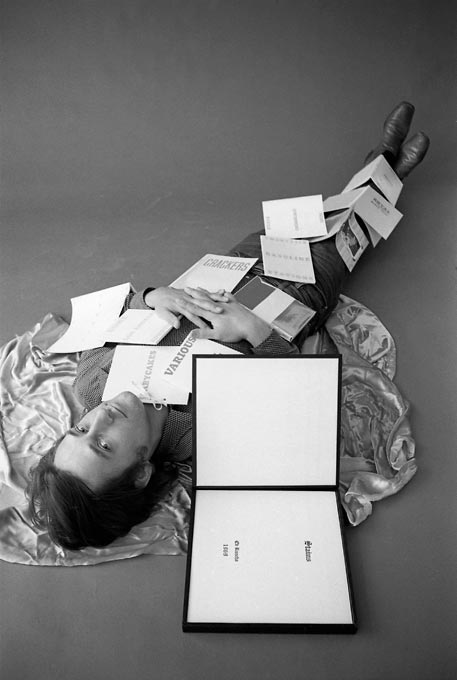

– I was shooting pictures of Ed, his wife and their little boy. Different kinds of pictures. Ed needed a picture for a show in Europe and wanted one with his books all over him. While we were getting ready for that, we did one with the books on his head. Years later, my gallery, Craig Krull, suggested I do a show with the pictures I had shot of Ed. I said I would need Ed’s approval. Ed said “I don’t know why anybody would want to do that but do what you want!” The show then turned into a book as well. The one with the books on his head photograph was chosen for the cover and since then, I get requests for it all the time. It was always very easy to work with Ed.

– Ed really liked that car, he bought it in Oklahama and drove it to Los Angeles. The picture came about because of a female journalist who came to our studios. She worked for The Hollywood Reporter, had heard about the three of us and wanted to do an article. She needed a picture to go with the article. We did three different types of photographs. I put the camera on a tripod, a 10-second delay and there was the picture. It turned out great, we all loved it, we still do, and it was typical of the way we were hanging out in those days.

– After I had shot the Jan series I went to Walter Hopps to discuss having a show at the Pasadena Art Museum and he said, “I’d love to show your work!”. I was all excited about it but no dates were set. But after I had come back to my studio, I looked at the Jan and Flag series and I thought to myself, “I would hate for people to look at my pictures and say, “That reminds me of so-and-so”. I needed something new, something different. I wanted people to look at my work and say, “That’s a Jerry McMillan”. I asked Walter Hopps if he would mind waiting? He was okay with it. Two and a half years later, I had done the work I needed, such as the bag series. So I tried calling Walter to say I was ready but he didn’t call me back! I even went to the museum but couldn’t find him. I was afraid I had blown it! I needed something to get his attention. So I created the photograph with the toaster, and I had to write the message backwards to get the reflection in the toaster. I made a big print of it, went to the museum, went upstairs to the offices and tacked it to his door. About 30 minutes after I got home, Walter called me, very excited about doing a show with me! He suggested showing me alongside René Magritte but the Magritte show was in summer, when nobody goes to museums in California. So instead, he suggested I show alongside a then unknown name, Joseph Cornell, in winter time 1966. And that was Cornell’s first solo show. A great memory.