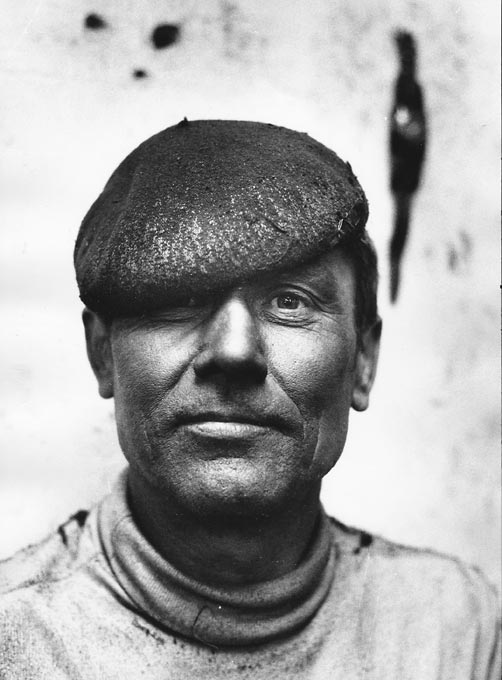

György Stalter, born in 1956, was one of the prominent names in the Hungarian Neo-Avant-Garde. In the mid-1970s, he began producing a series of striking, conceptual self-portraits. He was interviewed about them for an article about the history of the movement in issue five of The Classic.

Stalter later abandoned conceptual photography to focus on photojournalism, beginning with two projects about Roma, regarded in Hungary and many other countries as second-class citizens. Stalter told me about the two projects.

– My series of photojournalism are not traditional photographs. I believe they also carry some conceptual thinking. These picture are subjective, they reflect me, my relationship with the world surrounding me, my vulnerability, my emotions, as well as the people who have collaborated with me. With my photography I took a stand for the Roma people, living on the margins of society.

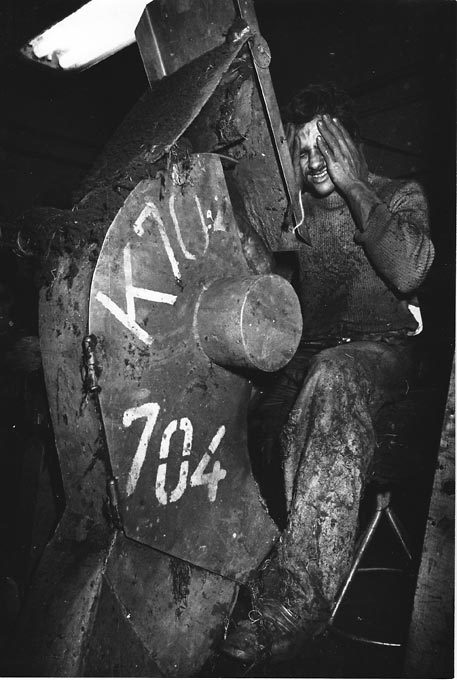

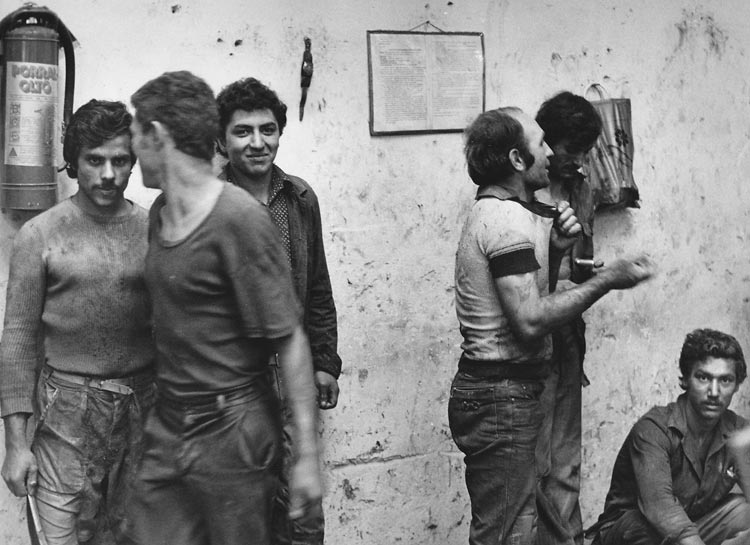

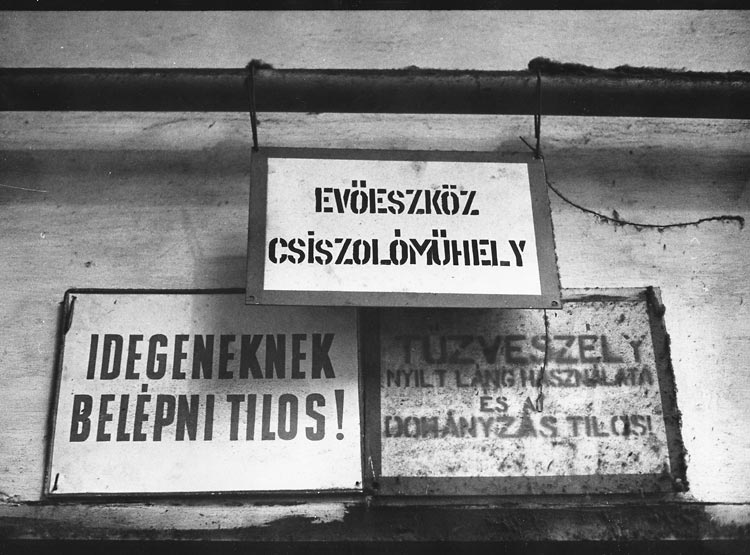

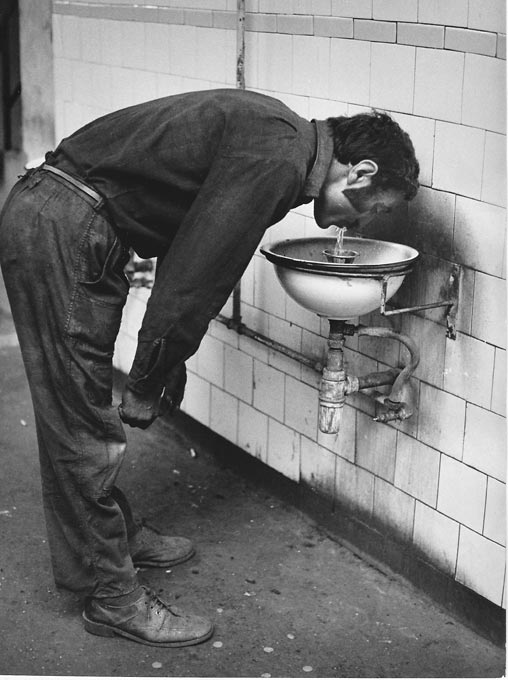

Manufacture, 1980, was the first of the two projects. Its subject: The Elzett Work Factories in Berettyóújfalu, a town in the centre of the Northern Great Plain Region in Eastern Hungary. Stalter had already been working at the editorial offices of Magyar Ifjúság, a Hungarian Youth weekly, for some years when he and a journalist were commissioned to do a series of photographs for the upcoming 1 May edition.

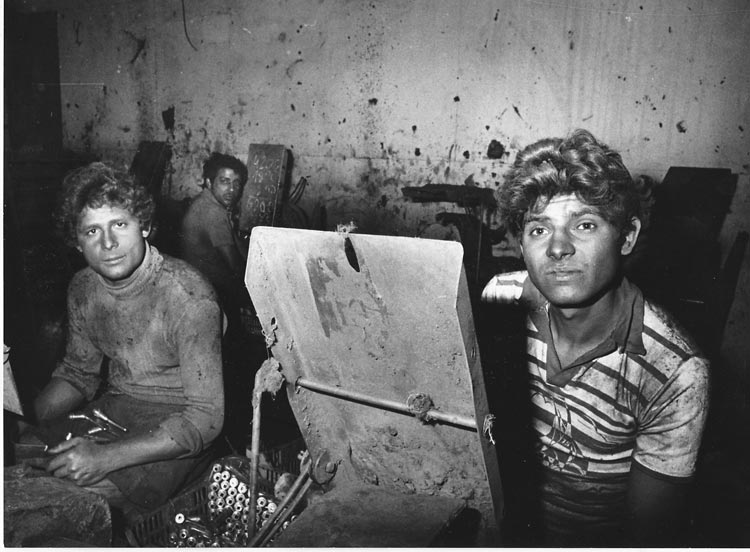

– It was to be a so-called “production report” about workers. I had already been to the Elzett Work Factories in Berettyóújfalu with a journalist colleague. We noted then that only Roma were working in one of the workshops and under inhumane conditions, polishing aluminium spoons. Although there was officially “full employment” at the time and KMK, that is “avoidance of work”, was severely punished as it was regarded as a danger to the public. No “white man” would accept such work, for the simple reason that it was a death sentence. The fine metal dust the workers inhaled was guaranteed to kill them within three years. So all the workers there were Roma, mostly young men, who had been given a stark choice: “Work at the polishing plant or go back to prison for parasitism.”

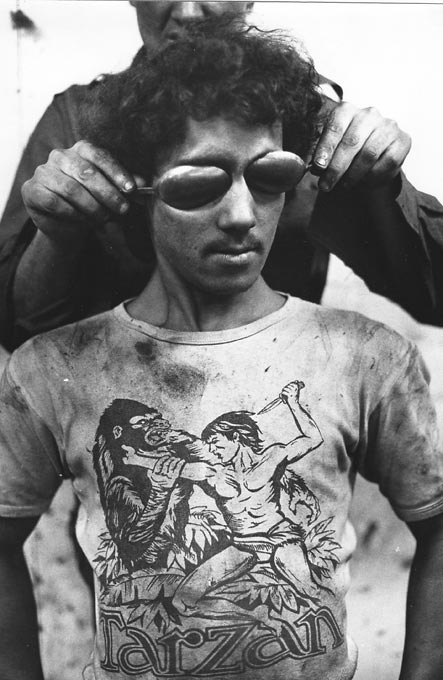

In one of the images, the eyes of a young man in a Tarzan t-shirt is covered by spoons, held by a friend standing behind, a reference to the tradition of placing coins on the eyes of the dead, here replaced by spoons, the fruit of their labour.

The editor of Magyar Ifjúság gave Stalter the go-ahead.

– I wanted to do the project as a series or a picture essay, so I returned to the factory several times. Seeing the material in progress, my boss was pleased: “At last, a new way of representing workers!” When the series was complete, it was shown to the copy editor, who also liked it very much, and who thought up the title Manufacture. He designed it as a three-page picture report, with captions but without any text. He showed it to the deputy editor. He also liked it, but said that he must “show it to the editor because of the nature of the piece.” The editor also liked it but said we should return to the subject after the holiday. I waited for a long time for the story to be published and started getting impatient. But it didn’t appear.

The answer came finally came back.

– I was told that the photographs painted such a black picture of the conditions at the plant that some text must be written to justify them. So they sent a journalist down, and he wrote an honest article. The project was then reduced to two pages including the text. Compared to the original idea, this version was no longer exciting to me, but even this was not published.

Meanwhile, Stalter entered the series in a press competition.

– I received first prize in the essay category. I happily informed the editors, and they said they were happy too. I asked, when the series would be published in the paper? The latest idea was to take it off the domestic politics pages, and put it into cultural supplement, calling it art photographs, winner of a competition. Time went by, but Manufacture was not published in any version whatsoever. I sometimes wonder if a weekly publication in today’s Hungary would publish it?

Manufacture now ranks as one of the high points of Hungarian photojournalism of the period, as does the project he carried out two years later, Tólápa, about the inhabitants of a small Roma village.

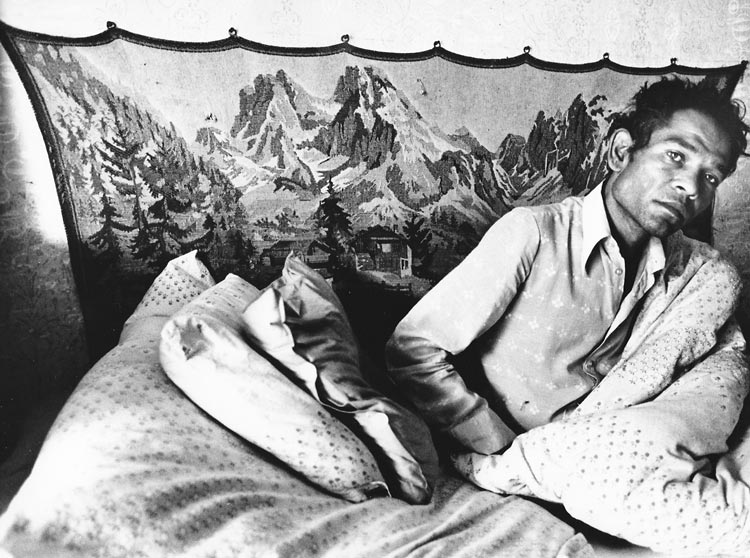

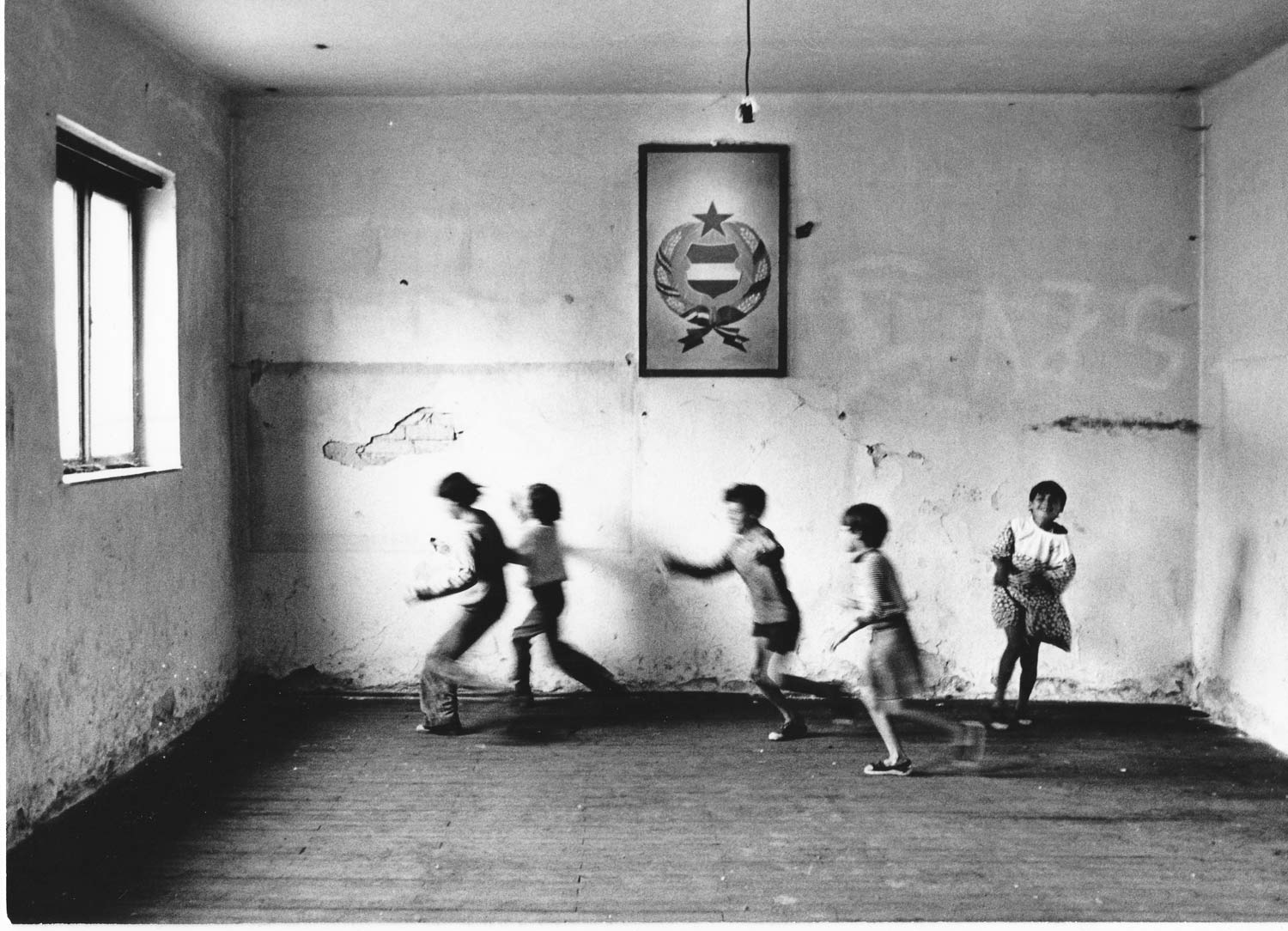

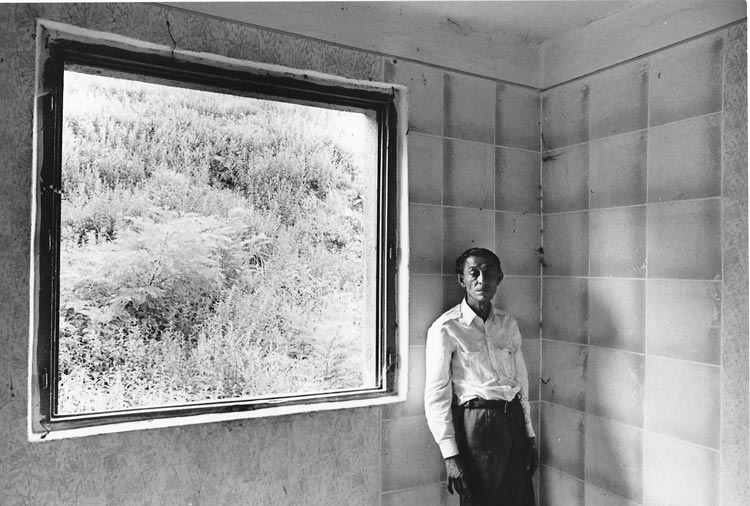

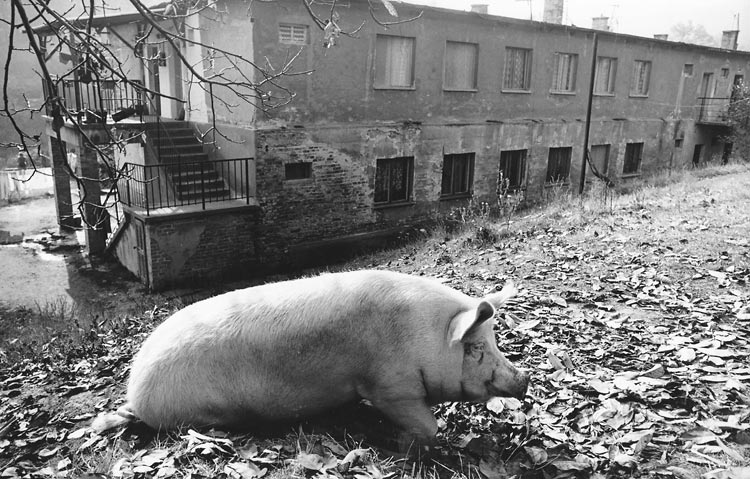

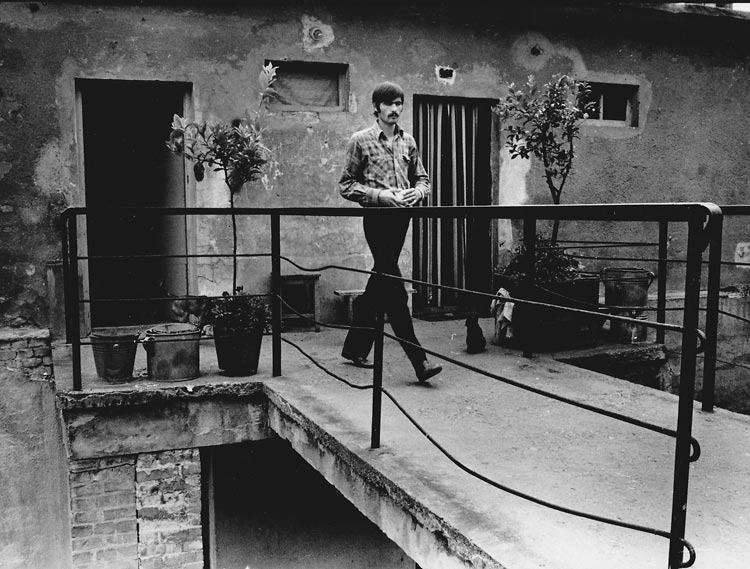

– Tólápa lies in North Eastern Hungary, close to the town of Ózd, which was one of the centres of heavy industry during the communist era. Tólápa was built by young delinquents who had been convicted for various criminal offences. During the period 1952-1956, it served as a prison colony, and after that, it became a colony for miners who were working in the region. Later on, it became a home for Roma. There were seven main buildings in the village , with altogether 103 apartments. When I visited, only 46 of them were occupied, by the 145 occupants.

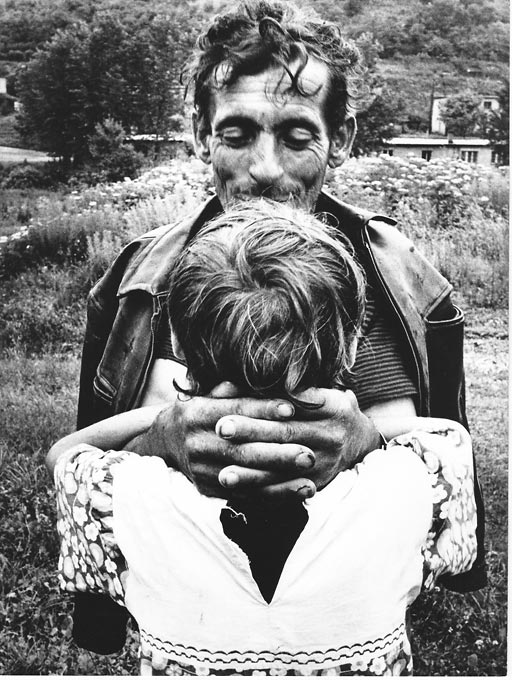

The houses are dilapidated, the inhabitants making conditions as bearable as they can, with plants, furnishings, religious pictures on the wall. A teenage clasps a gosling. An older man in suit and hat strides confidently down a dirt road. A group of young girls giggle as they play outside. Perhaps the most telling image of them all shows children a group of children playing in a former schoolroom, above them on the wall, the symbol of the People’s Republic of Hungary, the republic that despite its communist rhetoric would never accept them as fully-fledged citizens, forever pushing them to the margins of society. And the situation for the Roma in Hungary hasn’t improved after the fall of communism.

In the ’80s and ’90s, Stalter travelled to war and conflict zones, in Mozambique, Sudan, Ethiopia, as well as China, India and Cambodia. But he and his wife, Judit M. Horváth, would over the years photograph most of the Roma settlements in Hungary, small villages in the countryside as well as ghettos in the cities. Their images of Roma were published in 1998 in a book called Más Világ – Other World.