Collection, preservation, research, exhibitions and education together make up the bedrock of a museum’s work. The accompanying operational structures and conception of exhibition objects, on the other hand, have undergone substantial changes over the centuries. Among the holdings of the Städel Museum – which was founded as a civic foundation in Frankfurt am Main in 1815 – is a photography collection that, however little known to the public, offers insights into that development. The young medium made its debut in the Städel collection as far back as 1850. Yet it was not until the museum’s structural expansion in 2011 that the historical photographs were finally taken out of the cellar, where they had been stored as archival material, and integrated into the permanent collection. The chequered history of photography at the Städel illustrates how the medium’s status and perception have changed in the museum world as a whole. This article takes a closer look at the challenges presented by the reappraisal and expansion of the Städel’s photography collection.

The Collection’s Beginnings under Johann David Passavant

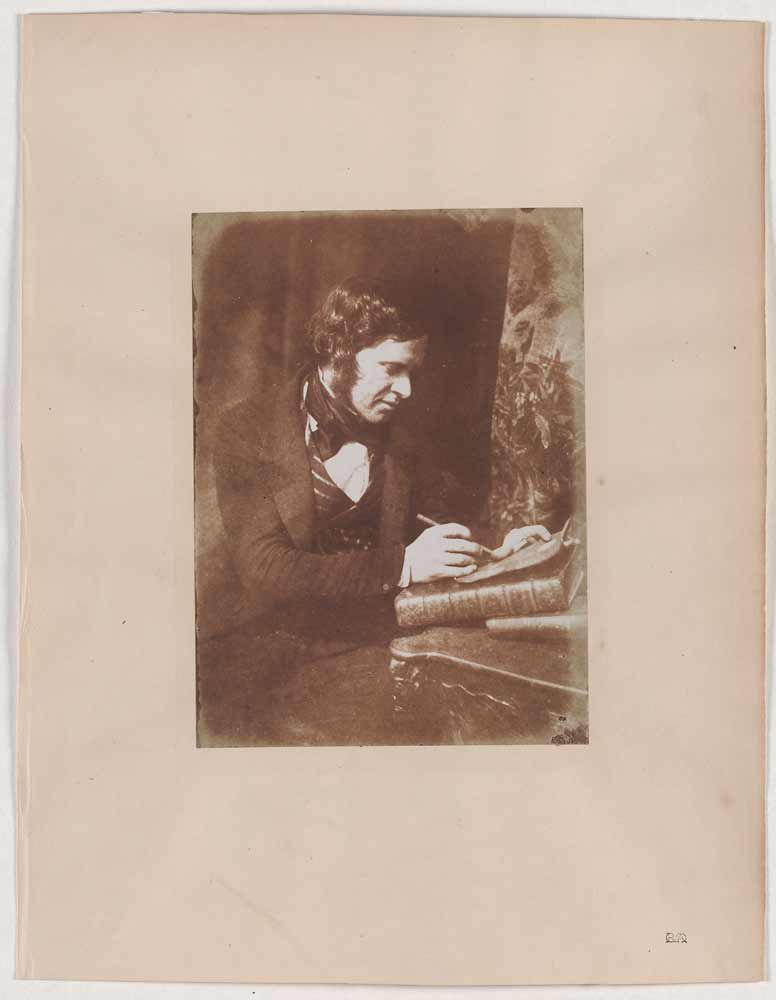

“I’ve put several trial photographs on display at the Städel’sches Kunst-Institut”, announced Frankfurt photographer Sigismund Gerothwohl (1808–before 1902) in 1845 in an advertising text in the news sheet of the Free City of Frankfurt.1Advertisement by Sigismund Gerothwohl in Intelligenz-Blatt der Freien Stadt Frankfurt, 5 April 1845 That presentation formed the prelude to the first exhibition of photographs ever to be mounted in a German art museum. 2Photography presentations had previously taken place in Kunstvereine (art associations) as well as industrial, commercial and world expositions. See Ulrich Pohlmann: “‘ Harmonie zwischen Kunst und Industrie’: Zur Geschichte der ersten Photoausstellungen”, in Bodo von Dewitz and Reinhard Matz, eds.: Silber und Salz: Zur Frühzeit der Photographie im deutschen Sprachraum 1839–1860, exh. cat. Josef-Haubrich Kunsthalle, Cologne, 9 June – 23 July 1989 (Heidelberg: Edition Braus, 1989), pp. 496–513. As far as we know today, the Frankfurt presentation was in fact the first photography exhibition to take place in an art museum anywhere in the world. See Felicity Grobien and Felix Krämer: “Lichtbilder: Photography at the Städel Museum from the Beginnings to 1960”, in Max Hollein and Felix Krämer, eds.: Lichtbilder: Photography at the Städel Museum from the Beginnings to 1960, exh. cat. Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main, 9 July – 5 October 2014 (Frankfurt am Main: Städel Museum, 2014), pp. XXVI–XXXI, here pp. XXVI/XXVII. Johann David Passavant (1787–1861), who directed the Städelsches Kunstinstitut (Städel Art Institute) from 1840 to 1861, had been an early champion of the new medium. The son of a mercantile family of Frankfurt, he had initially completed a banking apprenticeship before becoming a painter and joining the artists’ group known as the Nazarenes. He looked to the Old Masters of Germany and Italy for artistic inspiration and orientation – but also took a historical interest in them. Through his extensive research and publications on the art of the Renaissance, he made a name for himself as a scholar. Within that context, photography served him primarily as a means of making art accessible to a broad public – an aim he continued to pursue in his efforts to publicize the collection of the Städel Museum after becoming its director. At the art school affiliated with the museum since its founding, he moreover wanted the prints to be at the students’ disposal for working and study purposes.

Passavant had begun systematically acquiring photographs for the museum by the 1850s, if not before. The earliest evidence of an independent photographic collection is an exhibition announcement of 25 January 1852.3The advertisement of the exhibition in the Städelsches Kunstinstitut’s “Neu ausgestellte Gegenstände” (“Newly Exhibited Objects”) series announces that photographs of Venice “from the institute’s collections” would be on view, see Intelligenz-Blatt der Freien Stadt Frankfurt, 25 January 1852 The show featured views of Venice now no longer in the collection.4Altogether eighteen announcements of photography exhibitions at the Städelsches Kunstinstitut have been found for the period from 1850 to 1862. For an in-depth discussion of the subject, see Eberhard Mayer-Wegelin: “Early Photography, Frankfurt and the Städel”, in Hollein und Krämer 2014 (see note 2), pp. XLV–XLIX Apart from photographic cityscapes, landscapes and genre scenes, the Städel acquisitions also included reproductions of artworks from all over the world. Between 1854 and 1857, Passavant had the photographer Johann Schäfer (1822–before 1855) make photographic reproductions of drawings by Albrecht Dürer, Hans Holbein the Elder and Raphael for publication in an album.5Johann Schäfer: Photographisches Album nach Original-Handzeichnungen älterer Meister aus der Sammlung des Städel’schen Kunst-Instituts zu Frankfurt am Main, Frankfurt am Main, 1857 (Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main, call no.: 2/298) In 1854, the journal Didaskalia: Blätter für Geist, Gemüth und Publicität euphorically announced “an undertaking of which we can be confident that it will meet with due recognition, not only here in Frankfurt but everywhere there is a true love for art. It is, to our knowledge, the first undertaking of its kind, and purposes to put drawings by famous older artists that lie hidden away in museums, or at any rate can only rarely come to light, into the hands and personal possession of all friends of art.”6Anonymous: “Photographisches Album von J. Schäfer” (advertisement), in Didaskalia. Blätter für Geist, Gemüth und Publicität, 10 June 1854, quoted in: Eberhard Mayer-Wegelin: Frühe Photographie in Frankfurt am Main 1839–1870 (Munich: Schirmer/Mosel, 1982), pp. 34–36, here p. 35 Whereas in France and England there were already studios and publishing companies specializing in photographic reproductions of art,7For an in-depth discussion of this subject, see Dorothea Peters: “Zur Etablierung der Fotografie als Instrument der Kunstgeschichte: Der Verlag Gustav Schauer und die Berliner Museen 1860”, in Wojciech Bałus and Joanna Wolańska, eds.: Die Etablierung und Entwicklung des Faches Kunstgeschichte in Deutschland, Polen und Mitteleuropa, conference proceedings, 14th conference of the Arbeitskreis deutscher und polnischer Kunsthistoriker und Denkmalpfleger, Cracow, 26–30 September 2007 (Warsaw: Instytut Sztuki Polskiej Akademii Nauk, 2010), pp. 87–103, here pp. 90–92 the album was indeed unprecedented in Germany.8The systematic photographic documentation of German museum collections began in the 1860s. On the commercial distribution of photographic reproductions of art, see Dorothea Peters: “Reproduced Art: Early Photographic Campaigns in European Collections”, in Andrea Meyer and Bénédicte Savoy, eds.: The Museum is Open: Towards a Transnational History of Museums 1750–1940, series: Contact Zones, vol. 1 (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2014), pp. 45–57, and id. 2010 (see note 7), pp. 90–92

Passavant was meanwhile an established Raphael expert who had published a two-volume monograph on that artist in 1839. In collaboration with the Raphael Collection campaign initiated by Prince Albert in 1852,9Dorothea Peters: “From Prince Albert’s Raphael Collection to Giovanni Morelli: Photography and the Scientific Debates on Raphael in the Nineteenth Century”, in Costanza Caraffa, ed.: Photo Archives and the Photographic Memory of Art History, series: I Mandorli, vol. 4 (Berlin and Munich: Deutscher Kunstverlag, 2011), pp. 129–144; also see Martin Clayton: “Prince Albert’s Raphael Collection”, in Jonathan Marsden, ed.: Victoria & Albert: Art & Love (London: Royal Collection, 2010), pp. 176/177 he now embarked on the major project of documenting all Raphael drawings to be found in European collections at the time.10My thanks to Marie-Kathrin Blanck, who devoted her bachelor’s thesis to this subject in the context of early photography at the Städel Museum: Frühe Fotografie am Städelschen Kunstinstitut: Eine Untersuchung der Auseinandersetzung mit Fotografien in einem musealen, künstlerischen und kunstwissenschaftlichen Kontext unter Inspektor Johann David Passavant (1840 bis 1861) und deren heutiger Bedeutung, bachelor’s thesis, Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg, 2017, unpublished manuscript. Also see id.: “Die Raphael Collection: Royal Connections”, in StädelBlog, 31 May 2019, https://blog.staedelmuseum.de/die-raphael-collection-von-prinz-albert/ (accessed 17 April 2020) It was in this context that, in 1859, photographs of Raphael’s cartoons for the Sistine Chapel tapestries found their way from Hampton Court Palace in London to Frankfurt. Passavant had learned of the photographs’ existence from Ernst Becker, Prince Albert’s former librarian, who had been entrusted with a large share of the responsibility for the campaign.11I owe this information to Blanck’s thesis as well. See the letter of 21 January 1858 from Ernst Becker to Johann David Passavant (Universitätsbibliothek, J.C. Senckenberg, Frankfurt am Main, inv. no.: Ms. Ff. J.D. Passavant, A ll e, nos. 44, 46, 49) The very next year, the photographs “in the size of the originals”12In an advertisement of the “Neu ausgestellte Gegenstände” (“Newly Exhibited Objects”) series under the heading “Ferner aus den Sammlungen des Instituts” (“Also from the Institute’s Collections”), the exhibition title is given as “Photographien von den Kartons der Apostelgeschichte, von Raphael, in Hampton Court: Einzelne Teile in der Größe der Originale.”, see Intelligenz-Blatt der Freien Stadt Frankfurt, 16 September 1860.12 went on display in the rooms of the Städel Museum, offering the art-interested public an alternative to a trip to England to study the cartoons.13The photographs had been taken by Charles Thurston Thompson, the official photographer of the South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria and Albert Museum) in London. On the photographic reproductions of the works of Raphael for the Royal Collection, see Peters 2014 (see note 8), pp. 46–51. On Passavant’s connection to the project, see Hildegard Bauereisen: “Johann David Passavant”, in Margaret Stuffmann, ed.: Von Kunst und Kennerschaft: Die Graphische Sammlung im Städelschen Kunstinstitut unter Johann David Passavant 1840 bis 1861, exh. cat. Städel Museum, 24 November 1994 – 5 February 1995 (Frankfurt am Main: Städelsches Kunstinstitut und Städtische Galerie, 1994), pp. 13–40, here pp. 28/29. Elisabeth Schröter: “Raffael-Kult und Raffael-Forschung: Johann David Passavant und seine Raffael-Monographie im Kontext der Kunst und Kunstgeschichte seiner Zeit”, in Römisches Jahrbuch der Bibliotheca Hertziana, vol. 26 (1990), pp. 303–397, here p. 375 Drawings of the objects depicted are found in the margins of many of the collection’s early photographs – another indication of the great importance Passavant attached to photography not only for museum education purposes but also as study material. After all, his duties as the so-called Inspektor of the Städelsches Kunstinstitut also included teaching.

Passavant bequeathed a major portion of his own collection to the institution he had served for so long. Among his holdings were a large number of works by prominent photographers, including Maxime Du Camp (1822–1894), Charles Marville (1816–1879) and François Alphonse Fortier (1825–1882).14Through the bequest, 353 engravings, lithographs and photographs entered the Städel collection. See Schröter 1990 (see note 13), p. 376. On Passavant’s will, see the estate file at the Institut für Stadtgeschichte, Frankfurt am Main (inv. no. 1861/342) It was not until after his death in 1861 that inventories were drawn up and a classification system was introduced.15Jutta Schütt and Martin Sonnabend: “Sensitive Treasures: Drawings, Watercolours and Collages from the Städel Museum’s Graphic Art Collection”, in id., eds.: Masterpieces of the Department of Prints and Drawings, exh. cat. Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main (Petersberg: Imhof, 2008), pp. 9–20, here p. 13 In 1865, Gerhard Malss (1819–1885) – Passavant’s former right hand and his successor at the Städel – wrote a manual for the proper inventorying and cataloguing of objects, complete with a list of the different areas of the collection and brief information on the holdings.16Georg Malss: Instruction und Leitfaden zur Weiterführung der Kataloge und Inventarien, 1865 (Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main) A sub-category of the print room holdings, the photographs were classified geographically by author’s nationality. In the case of cityscapes and genre scenes, the deciding factor was the place depicted; photographic reproductions of artworks, on the other hand, were sorted according to where the respective artist had been active. Within the categories thus created, the works were ordered chronologically. The prints were kept in cardboard folders whose covers resembled those of books.

As far as we know, this system of order was retained until after the turn of the century. A major effort to reorganize the holdings got underway around 1908. Now all entries on photographs were deleted from the registers listing the prints and, under new object numbers, transferred to a separate inventory comprising several volumes, not all of which have survived. Owing to improvements in methods of image reproduction for books and magazines, photography had forfeited its function as an aid in conveying art-historical knowledge and was now classified as archival material. World War II wreaked havoc in the Städel’s art collections and archives,17Uwe Fleckner and Max Hollein, eds.: Museum im Widerspruch: Das Städel und der Nationalsozialismus, series: Schriften der Forschungsstelle “Entartete Kunst”, vol. 6 (Berlin: Akademie, 2011) and a substantial portion of the old photographic holdings and their history were irretrievably lost.

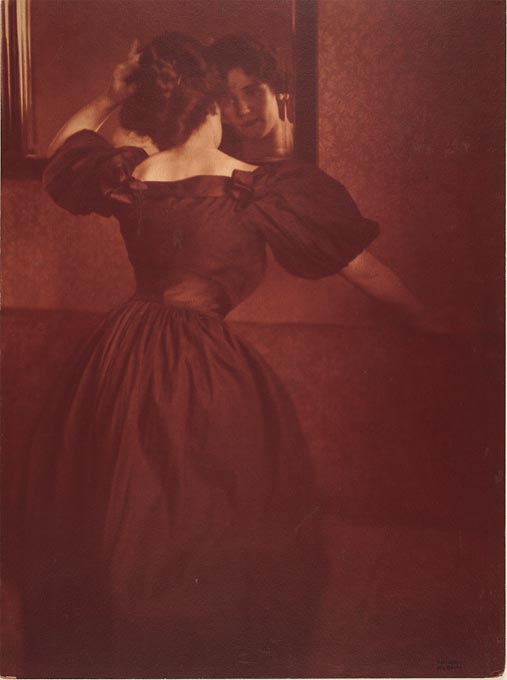

Rediscovery and a Fresh Start

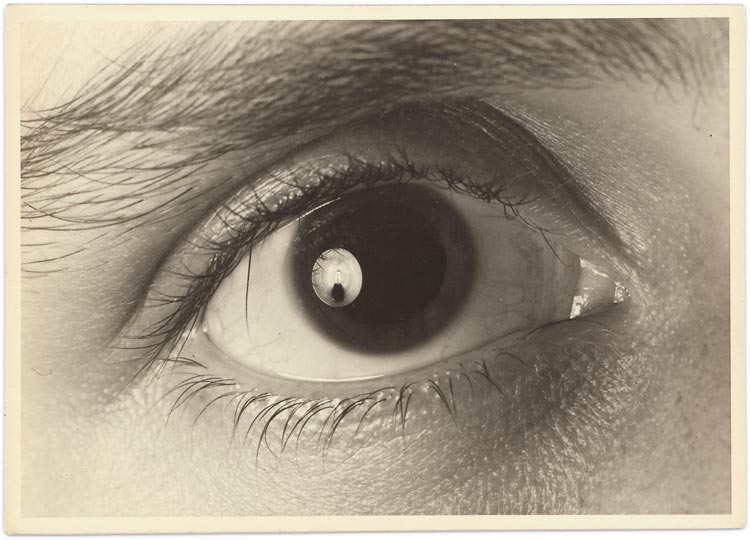

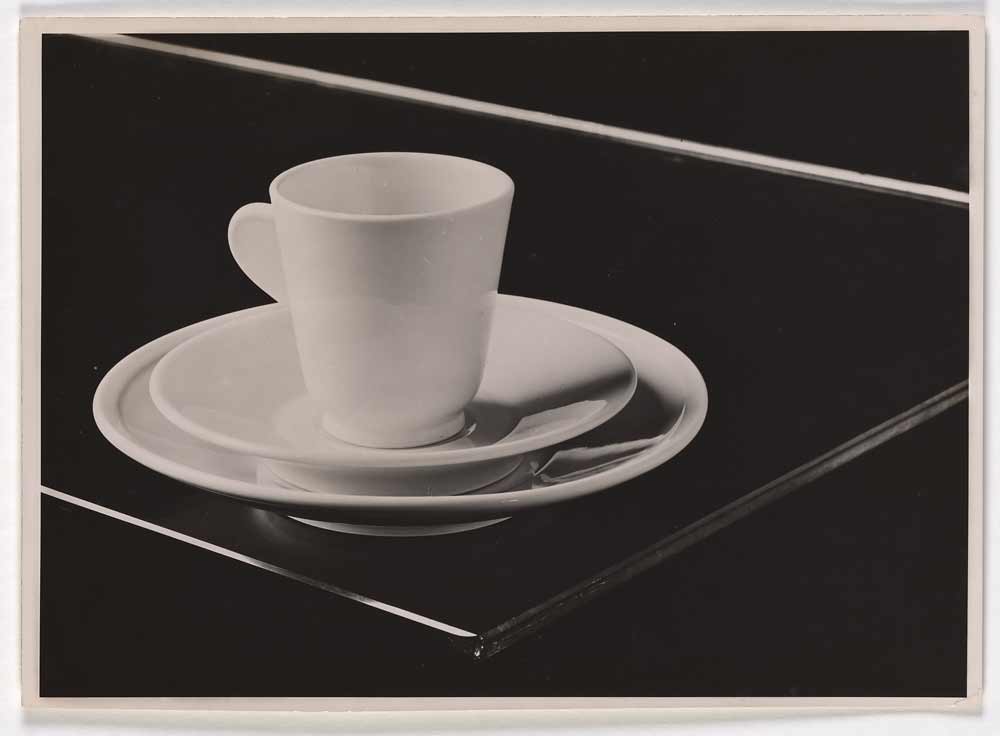

For a long time after Passavant, the photographs in the museum’s holdings no longer played a role as objects considered worthy of exhibition. It was not until 1993 – when the Städel presented a special exhibition of landscape photography by Gustave Le Gray (1820–1884) and Carleton E. Watkins (1829–1916) from the collections of the J. Paul Getty Museum – that attitudes towards the medium began to change again.18As explained in the introduction to the catalogue: “For the first time in its history, the Städel Department of Prints and Drawings is presenting a photography exhibition and thus devoting itself to an area that, for historical and material reasons, has hitherto not been a part of its field of activity.” Weston J. Naef and Margaret Stuffmann: “Vorwort”, in Margaret Stuffmann and Martin Sonnabend, eds.: Pioniere der Landschaftsphotographie: Gustave Le Gray, Carleton E. Watkins, exh. cat. Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main, 2 September – 7 November 1993 (Mainz: Hermann Schmidt, 1993), pp. 6–8, here p. 6 After the turn of the millennium, the acquisitions of three extensive collections expanded the Städel Museum’s photographic holdings. The first of these was an important group of primarily post-1960 photographic works that came to the Städel in 2008 as a permanent loan from the DZ Bank art collection. In 2011, Uta and Wilfried Wiegand placed some 200 photographs and 40 historical frames19On the framing of the photographs, see Wilfried Wiegand: “The Magic of Light: On Photography in an Art Museum”, in Hollein und Krämer 2014 (see note 2), pp. XXXVI–XXXIX, here pp. XXXVI/XXXVII in the museum’s possession. The Wiegand works reflect the development of photography from its beginnings to the early twentieth century with a special focus on the second half of the nineteenth. It features icons of photography such as Gustave Le Gray (1820–1884), Nadar (1820–1910), Julia Margaret Cameron (1815–1879), Eadweard Muybridge (1830–1904), Eugène Atget (1857–1927), Edward Steichen (1879–1973), Paul Outerbridge (1896–1958), Dora Maar (1907–1997) and André Kertész (1894–1985). These acquisitions sparked a renewed interest in the old holdings. Over a period of several years, the latter underwent investigation, reappraisal and incorporation into the museum’s modern collection. In 2013, through the agency of Galerie Kicken in Berlin, another large group of photographs, now dating mostly from the 1920s and 1930s, entered the Städel partially by purchase and partially by donation. The following year, the exhibition Lichtbilder: Photography at the Städel Museum from the Beginnings to 1960 provided an initial survey of the old and new photographic holdings. Thanks to these and further purchases and donations in the years that followed, the collection meanwhile comprises more than 5,000 photographs, of which 250 belong to the Department of Contemporary Art.20See the digital collection from the Städel Museum: https://sammlung.staedelmuseum.de/en

The Presentation of the Collection

As a result of these developments, it was decided that the extensive new photo holdings should be a permanent fixture in the presentation of the museum’s collection. Since the refurbishment of the old building and the opening of the Garden Halls for the presentation of contemporary art in 2011, photography has been continuously on view in the Städel Museum’s exhibition galleries. Thanks to its presentation side by side with painting and sculpture, visitors can experience how photographs interact with works in other mediums. The acquisition of the Wiegand Collection complete with its historical frames inspired the museum curators to devise a concept providing for the individual framing of every photograph. Frames were produced in various formats and colours and with different styles of moulding so that each photograph can be exhibited in a frame corresponding aesthetically to its respective epoch.21In a comparison with the Städel Museum, already Miriam Szwast of the Museum Ludwig called attention to the German museums’ differing conceptions of frames as a form of presentation for photography: Miriam Halwani (now Szwast): “Revision: Perspektiven der historischen Fotografie im Kölner Museum Ludwig”, Rundbrief Fotografie, vol. 22 (2015), no. 2, pp. 38–49, here pp. 43–46

As many of the photographs are highly sensitive to light, they are presented in small side galleries where the level of luminosity can be adjusted. The prints are exchanged every six months, not only to ensure variety in the display, but also to guarantee the works’ longevity. Many museums meanwhile have reproductions of their photographs made for presentation in their own galleries and above all for lending purposes. In the interest of preserving the aura of the original, the Städel Museum has generally refrained from this practice. Only prints authorized by the photographer or his/her estate are offered as an alternative to the original when a request comes at short notice. There are approximately 170 such prints in the holdings. The Städel thus ascribes paramount importance to the appreciation of the historical object, even if it means that many prints can be placed on exhibit only rarely and for brief periods of time. No copy is capable of perfectly reproducing the gradations in tonal value painstakingly achieved by the photographer in the vintage print.22On the term “vintage”, see Timm Rautert, ed.: Vintage (Göttingen: Steidl, 2016) And particularly in the photography medium, there are always numerous still-to-be-discovered alternatives when the legendary work of choice is not available. In the future, the Städel Museum will present photography increasingly in small, thematically oriented cabinet exhibitions exploring how its photographic holdings relate to aspects of art history.23In the past, cabinet presentations have taken place on themes such as Carl Friedrich Mylius: Frankfurt Forever! (2019), Fotografie in der Weimarer Republik: Ein neuer Blick auf die Wirklichkeit (2017) and Frühe Fotografie im Städel: Vom Lehrbild zum Kunstwerk (2013)

Research

In view of the collection’s considerable expansion, the job of researching the photographs’ history posed quite a challenge to the Department of Modern Art. Whereas in the case of acquisitions from estates and publishing company archives, the prints’ original use is generally known, the same is not true of works from galleries or private collections. Being an art museum, the Städel chose them according to aesthetic criteria. Susan Sontag equates photographs with empty projection surfaces and observes: “Because each photograph is only a fragment, its moral and emotional weight depends on where it is inserted. A photograph changes according to the context in which it is seen.”24Susan Sontag: “The Heroism of Vision” in id.: On Photography (New York: RosettaBooks, 2005), https://www.academia.edu/26633066/PHOT_Susan_Sontag_On_Photography (accessed 25 August 2020), pp. 65–87, here p. 82 The study of the collection that followed in the wake of the acquisitions accordingly focused on the contexts in which the photographs had been taken and their original uses. The aim was to gain an understanding of the works’ content against the background of their utilization. To pursue the matter of the photographers’ praxis means to examine the images within the “photographic dispositif”:25For an in-depth discussion of the “photographic dispositif”, see Katharina Sykora, Kristin Schrader, Dietmar Kohler, Natascha Pohlmann and Daniel Bühler, eds.: Valenzen fotografischen Zeigens, series: Das fotografische Dispositiv, vol. 3 (Kromsdorf: Jonas, 2016) photographs demand contemplation within a complex of actions comprising a range of political, aesthetic and economic preferences.

Museum Education Work

In the museum context, photography offers new ways of seeing that can apply to all artistic mediums. In 1815, in the foundation deed of what would soon be called the Städelsches Kunstinstitut, Johann Friedrich Städel stipulated that his collection “be opened to budding artists and art enthusiasts … for use and study.”26Johann Friedrich Städel: Deed of Foundation, 1817, p. 5, contained in the will of 15 March 1815, quoted in: Eva Mongi-Vollmer: “‘… denn ein Haus nur, nicht eine Festung der Kunst will er sein.’ 200 Jahre Kunst im Städel Museum”, in Max Hollein, ed.: Dialog der Meisterwerke: Hoher Besuch zum Jubiläum, exh. cat. Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main, 7 October 2015 – 17 January 2016 (Cologne: Wienand, 2015), pp. 12–19, here p. 13 In keeping with this wish, photography is meanwhile an integral part of the permanent presentation. The history of the Städel’s photography collection, with all its vicissitudes, mirrors the development of our understanding of photography as a medium in general: from its function as an educational aid in the art-historical study collection to its gradual transition to the status of archival material, and finally its present-day perception – once again – as an art form.

Kristina Lemke, M.A. is the Associate Curator for Photography in the Department of Modern Art at the Städel Museum, Dürerstrasse 2, 60596 Frankfurt am Main.

www.staedelmuseum.de