Getty Images’ collection of photographs attributed to Carleton E. Watkins (1829-1916) are a wonder of photography in every sense. The nineteenth century plates themselves are an impressive 18 x 22 inches in size, printed from window pane sized glass negatives which in turn were taken on a custom-built camera of immense proportions. These are some of the renowned views of Yosemite, in the Sierra Nevada Mountains, which so impressed an awestruck American public that Congress passed a bill paving the way for the first and arguably the greatest of the United States national parks.

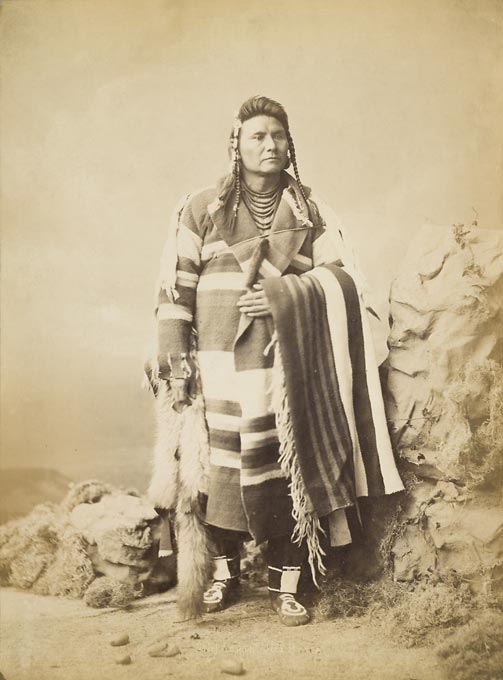

Watkins’ life is equally grand – a story of opportunity and vision tainted with tragedy and finally madness. Watkins was born in New York in 1829 and twenty-one years later joined the steady stream of fortune hungry pioneers heading west to California and Gold Rush territory. Following various odd jobs, including working as a teamster and a carpenter, in 1853 he found himself in San Francisco standing in for an absent employee in a daguerreotype studio. Before long Watkins was running his own portraiture business and photographing for land fraud disputes. Experimenting with different photographic methods, he found the wet plate process perfect for multiple print making and therefore commercial exploitation.

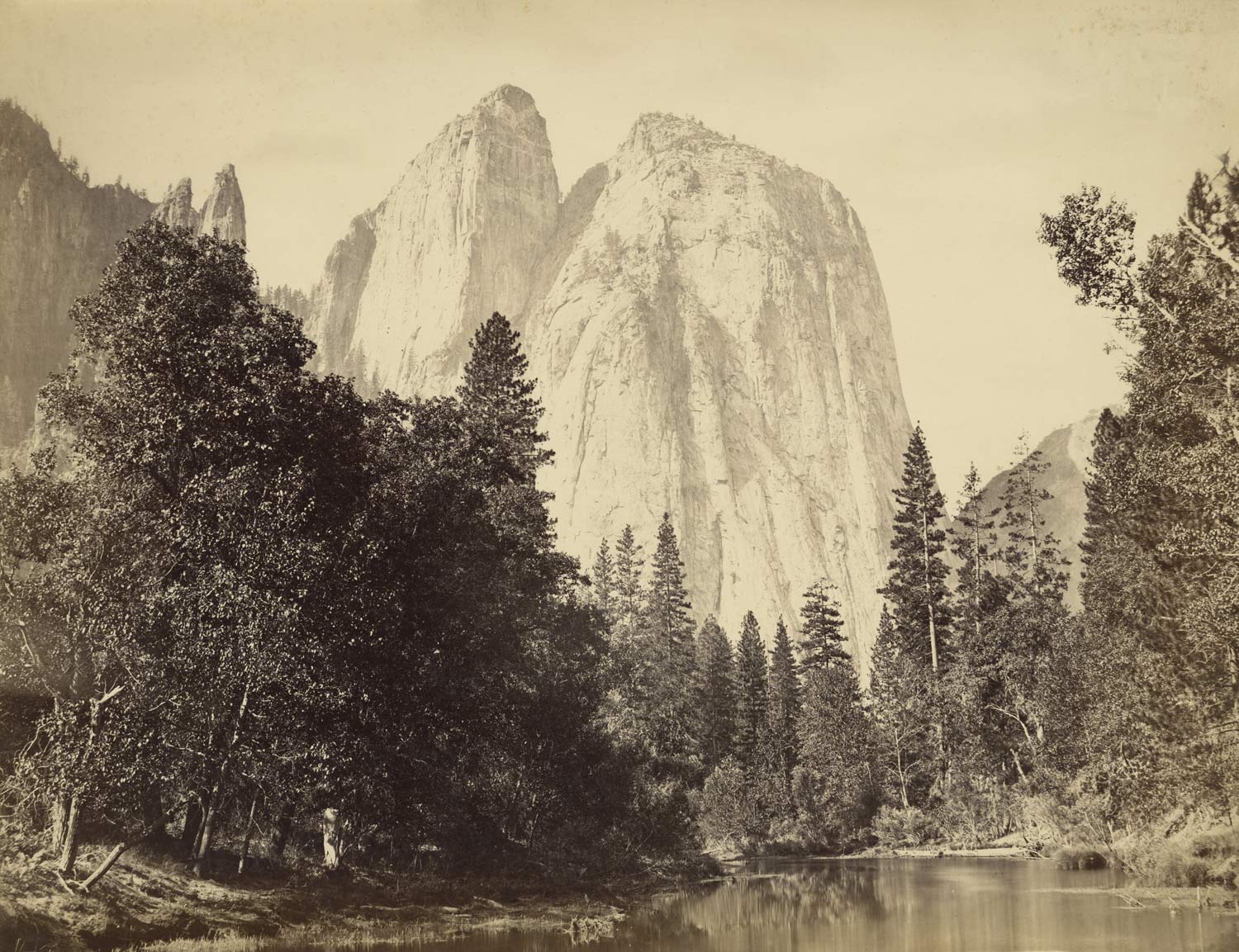

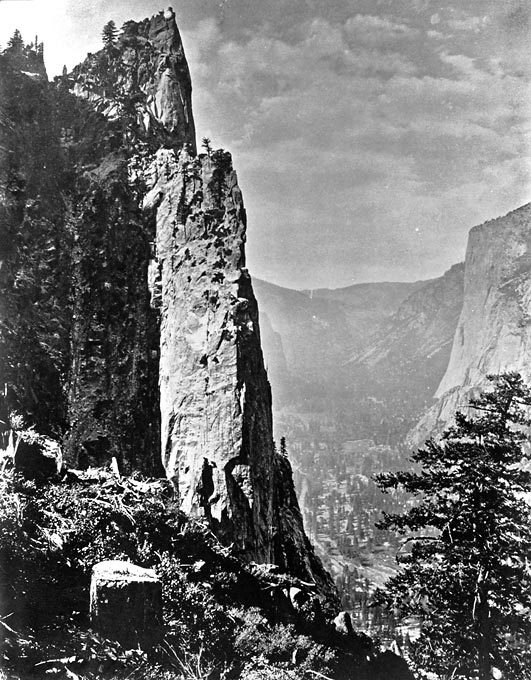

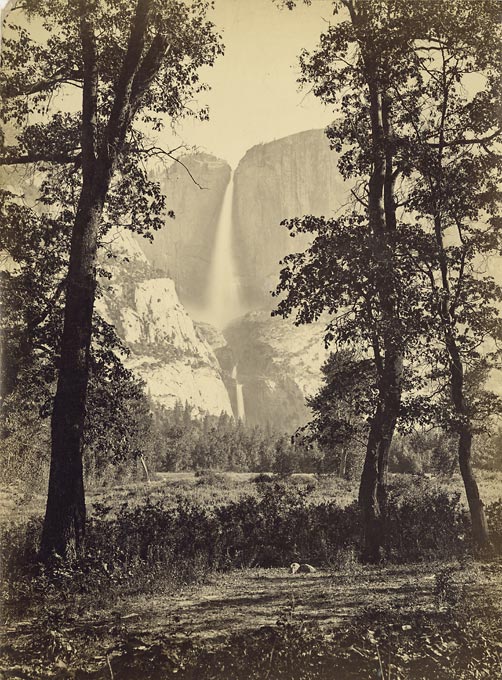

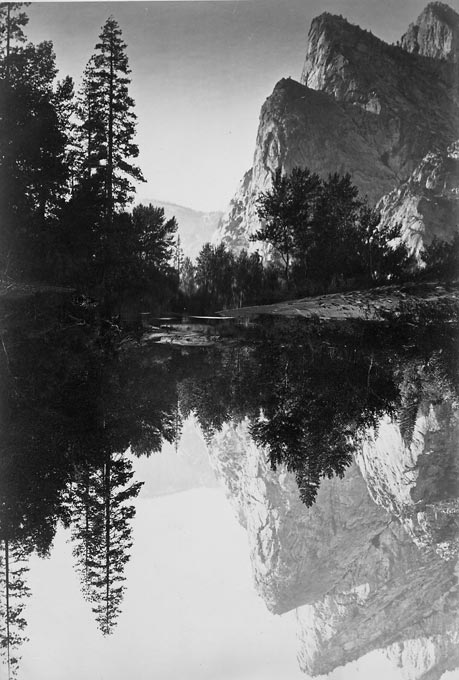

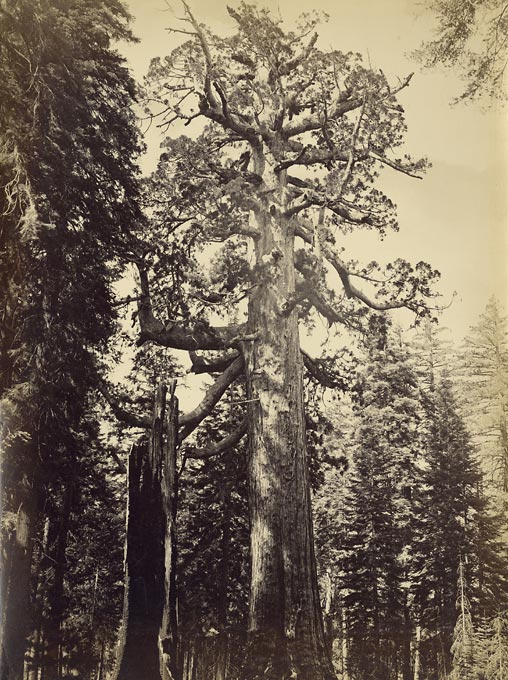

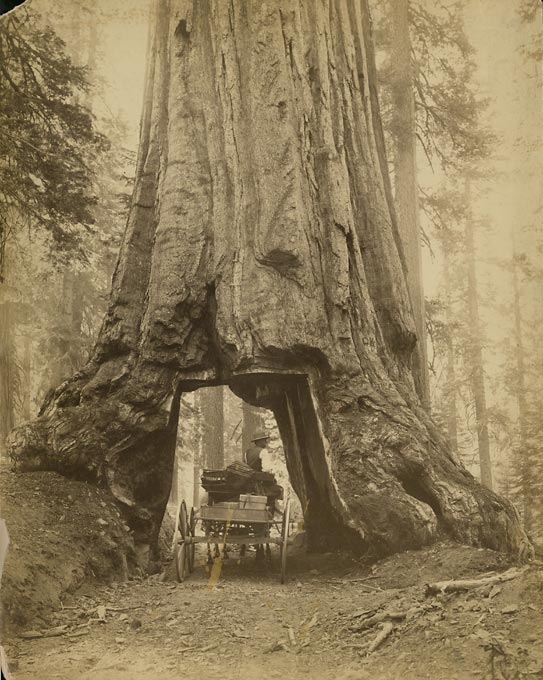

In the summer of 1861, Watkins first travelled to the remote and unexplored Yosemite Valley and Mariposa Grove of Big Trees, two hundred miles east of San Francisco, to photograph their fabled wonders. Having realised the standard cameras of the day could not capture the splendour and magnitude of such a landscape, he instructed a cabinet maker to fashion a “mammoth camera” – thirty inches in length and at least three feet when extended. With a team of mules loaded with this behemoth and its windowpane sized glass plates, a stereoscopic camera and yet more glass, tripods, a darkroom tent, all the other photographic paraphernalia required and camping supplies to last several weeks he set out over rough terrain, precipitous mountain passes and stupendous valleys of Yosemite. In an almost incomprehensible achievement, he produced thirty mammoth plates and a hundred stereos during the trip. They were among the first photographs of Yosemite seen in the East, stunning a public who hitherto had no idea of the natural treasures of their own vast country. Even today the scale of the images is jaw-dropping. In an almost comic “Where’s Waldo?” style Watkins often includes a person – perhaps his assistant Turrill – so tiny in frame as to be virtually impossible to spot but magnifying the scale El Capitan or half Dome. Partly on the strength of Watkins’s photographs, President Abraham Lincoln signed the Yosemite Bill of 1864 to protect the area from development and commercial exploitation, paving the way for the US National Parks system – and making Congress the first government in the world to move to protect its own territories for posterity.

With his reputation securely established, Watkins spent the next two decades creating some of the finest American landscape photographs of the nineteenth century. He was hired to photograph Yosemite for the California State Geological Survey and in 1867 opened his own ‘Yosemite Art Gallery’ in San Francisco. However, the financial panic of the mid 1970s coupled with his own exorbitant pricing bankrupted his business and he lost all his assets, including plates and equipment, to another photographer.

Undeterred Watkins covered thousands of miles traveling north to south from British Colombia down to the Mexican border and from San Francisco eastward as far as Yellowstone. He made great use for the Central and Southern Pacific Railroads to transport his equipment, slowly rebuilding his business, but by the end of the century his eyesight was all but gone and he increasingly relied on his assistant Turrill for help. In a final cruel twist, the great San Francisco earthquake and fire of 1906 destroyed the contents of his new studio, which he had wanted to preserve at Stanford University. Seriously unbalanced, Watkins was committed to the Napa State Hospital for the Insane in 1910, where he died six years later.

The Watkins’ collection was acquired by the Hulton Picture Post Library as part of the Augustin Rischgitz acquisition incorporating the London Stereoscopic archive, in 1947 and is now part of Hulton|Archive, a division of Getty Images.