How the Paris 1963 Bubble story for Harper’s Bazaar came to be a reality

In early December 1962, Nancy White, the editor of Harper’s Bazaar, called to tell me that I had been chosen to photograph the Spring Collections in Paris. This exciting news triggered an idea that had been hibernating for a long time.

On my 14th birthday, my father took me to a bookstore where I came upon a book of paintings by Hieronymus Bosch and found myself spellbound by the detail of a man and a woman in a veined caul-like bubble growing from a strange plant. That image in The Garden of Earthly Delights had a profound effect on me—it resulted in a recurring daydream of myself in a bubble floating across exotic landscapes.

I was excited when the idea of shooting the Collections in a Plexiglas bubble suddenly came to mind, only to give way to many reservations that made the project seem increasingly unrealistic. Once committed, there would be no turning back. The project at this point had become so intriguing that adventure overtook reason and moved on as if of its own volition.

Ali MacGraw was my personal assistant, stylist, and producer. We had met a few years earlier at Harper’s Bazaar where Ali worked as Diana Vreeland’s assistant. Ali was a gifted communicator who could translate ideas and make them readily accessible to art directors and editors. Ali would make sketches of my ideas as I related them to clients. The drawings were a great relief, as they were instant depictions of my ideas that readily seduced the viewer.

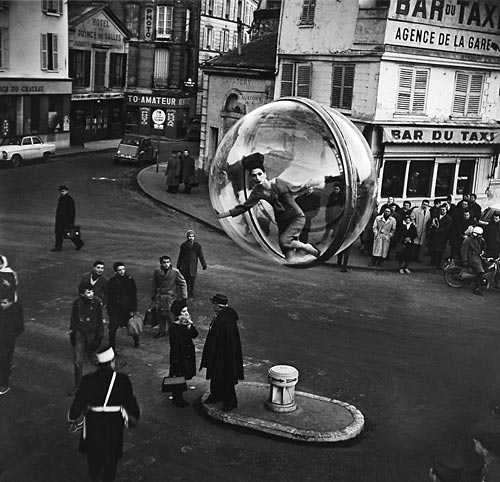

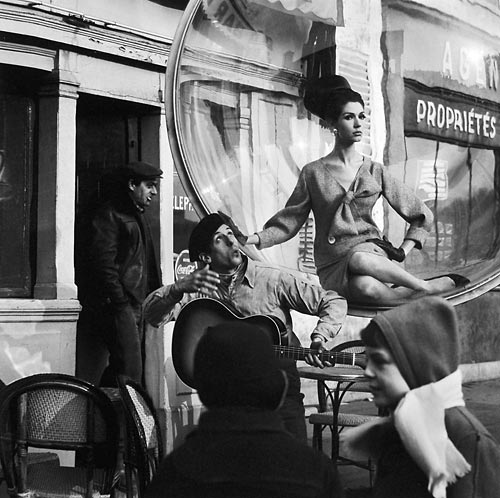

Eli Pollack was my studio chief and collaborator in the construction of devices that helped transform my ideas into reality. The bubble was rendered from a design that I sketched on a brown paper bag. It went through a battery of rigging and safety tests and then made its maiden flight in my studio. Simone d’Aillencourt, my favorite model at that time, walked up to the bubble, which was suspended from one of the studio skylights. She studied it, smiled, and remarked, ‘You’re going to fly it over the Eiffel Tower, yes?’ Suppressing a grin, I said, ‘Maybe.’ Simone climbed into the bubble and explored the walls of the sphere as if to find a new body language that would express the future in the strange spacecraft.

I shot the cover for the March 1963 issue of Harper’s Bazaar with Simone in the bubble overhanging the cliffs of Weehawken, New Jersey. The shoot went off without a hitch creating a memorable iconic image.

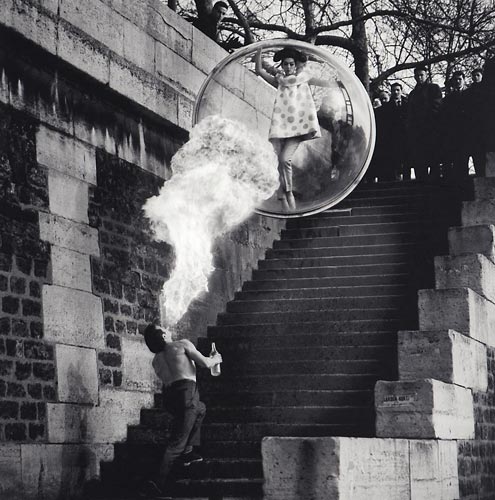

On January 20, 1963, my team and I flew to Paris to photograph the Spring Collections. The telescopic crane we hired drove up to the designated spot, followed by a small van. Its rear doors opened to reveal the bubble nestled in its cradle. Guy, the crane operator, then lowered the ¾ inch cable over the bubble so that Eli could attach a fine 1/8 inch, barely visible aircraft cable to the grapple. The bubble seemed to defy gravity.

The bubble was suspended a few feet off the ground and hinged at the top like a Fabergé egg; for easy entry. Guy was at the crane’s controls eagerly following the hand signals of his partner Michel as the bubble was guided to the final position. The morning we shot on the Seine River, Michel’s overzealous hand gestures overdirected Guy to lower the bubble into the water, flooding it up to Simone’s ankles and ruining an important pair of designer shoes.

I was made aware that photography in and around Paris was under the jurisdiction of the Beaux-Arts, which required three months prior notice for the necessary permits. I enlisted my friend Serge Marquand, a well-known character actor in France, and appointed him as our official liaison because I was aware of his friendship with the Chief of Police. Serge cajoled his card-playing partner (Chief of Police) into bending all the rules in order to accommodate our shoot. I might add that Serge was a madcap joker who would do anything for a laugh.

On the morning of the last shoot, Serge and the Chief were nowhere to be found. We exposed one and a half rolls of film without them, when a convoy of police cars immediately surrounded us. My assistant and printer Francesco Finnochio, who spent many sleepless nights keeping up with the schedule and propelled the team with his dry humor, took the camera from my hands and pretended to photograph Simone in the bubble. I was puzzled, as he covertly stuffed the rolls of film and a Hasselblad magazine into my pocket. The police began to swarm and arrest the crew. I slipped into a taxi as everyone else was hauled away in the French equivalent of a paddy wagon.

Hours later, I met up with Francesco and the crew in the lobby of the St. Regis Hotel. I reached into my pocket and handed Francesco the undeveloped rolls of film. He looked angrily at me and said, ‘I thought you would’ve developed the film by now. We’re never going to make the deadline.’ Suddenly, he broke into a broad smile. ‘Congratulations, kid,’ he said. ‘This collection is now history.’

Making models fly in Paris in 1965

On a cold winter morning in December 1964, I received a call from Nancy White, the editor-in-chief of Harper’s Bazaar, who asked, with a playful lilt in her voice, “Can you rival the best of Sokolsky? If you can, it would be my pleasure to send you to Paris to shoot the Spring Collections.” I had an idea that I always wanted to shoot for the Collections and decided to go for it. Nancy said, “You sound excited?” In an effort to sound amusing, I said, “Nancy, come fly with me.” There was a long silence on the phone. I broke the silence and told her, “Yes the girls will be flying, and if you are worried, I will shoot a test for you to see.”

I had the flying rig made by a corset store that fabricated corrective devices for the handicapped. I designed a corset that resembled a pair of canvas cutoff jeans that stopped just under the breasts. It laced up the sides and had an aluminum spinal plate riveted to the back of the corset. Three rings were fastened to the spinal plate to accommodate the cable that allowed for variations of camera angles. The next task was to cast the model that was best suited for flying. After five years of shooting at Harper’s Bazaar, I was aware that the world of fashion was a fertile arena for gossip, so everyone at the studio was sworn to secrecy. The models were attached to a cable rigged from the lighting grid in the ceiling, and they practiced their gestures of flying.

Ali MacGraw, my assistant and producer, came into the studio, locked the door behind her, and whispered into my ear, “Would you believe Salvador Dalí is here? He wants to watch you fly the girls. Should I let him in?

“You’re not joking?”

“I’m not joking.”

Dalí came into the studio, introduced himself and announced, “Sokolsky, make Dalí fly.” When I told him he would have to wear a flying rig, he went ballistic. “Sokolsky, make Dalí fly!” Dalí refused to believe that I actually flew the models attached to a cable. He was under the impression that I was trying to deceive him and pleaded that I share my secrets of levitation with him. The Sixties were a time when the myths of science fiction were becoming everyday realities. I had actually borrowed my idea from watching weightless astronauts float about in their space capsules. I told Dalí I could make him fly, but it was very complicated and expensive. Dalí smiled and invited me to lunch with his wife Gala to discuss our new adventure trying to get him airborne.

We were having lunch at the fashionable La Caravelle in New York where Gala looked at me directly and said, “Dalí told me you are going to make him fly. How will you make him fly?” I told her I planned to charter a military cargo jet and, with the help of Dalí, design an amphitheater within the cargo space that resembled the Roman Coliseum. It would be elliptical in shape, and the faux stone benches would be occupied by artists, architects, writers, movie stars, and all the other personalities who cared to share our adventure.

I proposed that Dalí wear magnetic-soled shoes and stand on a raised metal plinth in the center of the amphitheater. With the aid of a crutch that was welded to the plinth, he would be strapped to it with an aircraft seatbelt. All of the occupants would be fastened into their prospective places, including myself, on a shooting platform overlooking the extravaganza. The Lockheed Martin C-141 would take off and fly in a parabolic arc when it reached the proper altitude. At a predetermined time, weightlessness would occur, the seat belts would be released, and I would shoot the floating celebrities as they were orchestrated by Dalí flying above them.

Gala looked at me as if I was a madman, formed a cross with her forefingers, extended her arms in my direction and shouted, “Diablo, Diablo, Diablo!” Lunch came to a wearying end as Dalí and I quietly made small talk about the cost and how amazing the project would be.

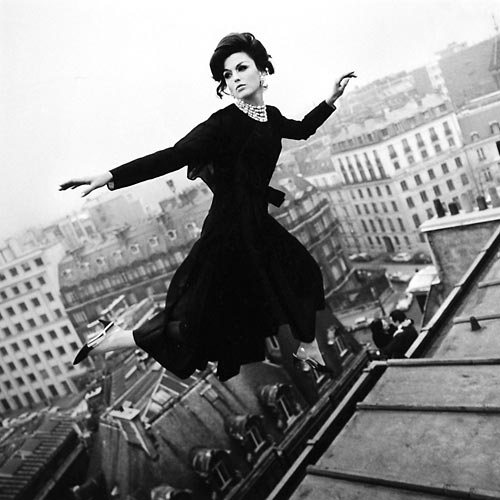

Getting back to the venture at hand, I chose Dorothea McGowan to be the flyer. I shot the old-fashioned way by suspending her from a very fine steel cable. In terms of efficiency and mobility, I decided not to use a crane, instead I designed a device that looked like a telescopic fishing pole made of aircraft aluminum. The fishing pole was centrally pivoted on a welded steel tripod. Dorothea was suspended from the cable at one end of the fishing pole. Two crew members who controlled a mechanical winch sat on the opposite end of the fishing pole to counterbalance her weight. The flying rig was portable and easy to set up almost anywhere, and most importantly, it did not require a crane.

The location for the first shoot took place in the dining room of the San Regis Hotel in Paris. The set up and shoot took about an hour. The diners in the picture were friends and models who took their places at the tables in the dining room. The magic began with my instruction to the diners to ignore the fact that Dorothea was flying above them. Watching Dorothea dangling from the end of the counterbalanced fishing pole was an inspiring event to behold. There were moments looking through the camera that seduced me into believing that she was actually flying.

The next and most dangerous of the flying shoots was the image I call “Fly Dior,” which took place on the roof of the San Regis Hotel. Watching Dorothea dangle five stories above the street from a thin cable anchored to a steeply angled roof was unsettling. To this day, I can picture her flying above the city, bouncing at the end of the cable, actually enjoying the experience. It was as if the shoot was preordained and Dorothea’s life was in my hands and I treated the privilege as if she was someone in my own family. No one ever questioned what we were doing.

The spirit of the Sixties was highly seductive, as if creating unique images was one’s true mission in life. Looking back, I realize the Sixties were a time when belief in the artist was so great that it transcended most business protocols. It was a time when I was passionately stirred to follow my dreams, and I did. I am truly happy to share those experiences today. I salute Dorothea McGowan for her unique gift as an artist and most importantly as a human being.

For more about The Melvin Sokolsky Room, visit Willem Photographic.