A quarter of a century has passed since the death of an artistic legend. We dive deep into his archive to unearth his sublime artworks and remember his story.

Art has the capacity to balance seemingly incompatible qualities — self-expression and communal tribute, tangible materiality and metaphysical essence, fading ephemerality and boundless eternity. American artist Steven Arnold (1943-1994) embodied these dualities, proving that the dark shadow of death cannot exist without the shining light of life, his enduring legacy is memorialized in a new documentary Steven Arnold: Heavenly Bodies.

When Arnold died in 1994 amid the AIDS crisis, he left behind a vast body of work. During his life, he fluttered between different modes of art-making — painting, drawing, sculpture, film, photography, fashion, and set design. A pioneer of cultural revolution, Arnold was at the forefront of counter-culture in the ‘60s, but meandering through different eras with an indulgent grace, he defied limiting himself to one genre or style. In the ‘70s, he was a dashing surrealist, in the ‘80s, a mystical revisionist historian. Today he’s often remembered for his role in launching the gender-bending performance troupe the Cockettes and for studying under Salvador Dalí as his protégé.

Premiering at Outfest at MOCA Grand in Los Angeles last year, director Vishnu Dass’s biographical documentary brings together interviews with friends like Simon Doonan, Rumi Missabu, and Holly Woodlawn along with photos and other artworks from the Steven Arnold Archive to illustrate the rich tapestry of the artist’s singular life.

Together these elements work to narrate Arnold’s artistic passage, from an imaginative student, through his experiments with film and psychedelics, and on toward his founding a studio in Los Angeles in the 80s, where he began his distinctive black-and-white tableau vivant photography.

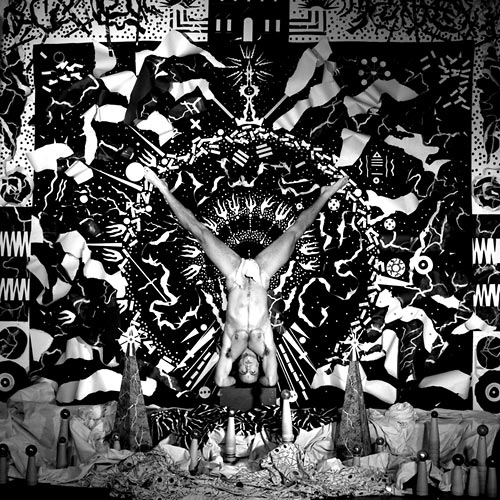

Arnold named his studio ‘Zanzibar,’ a tribute to a large, smiling Barnum and Bailey clown mask that he bought at a swap meet when he was a teenager. A few times, the mask found its way into Arnold’s photographs, a gesture to humor and artifice, both key to his image-making practice. On his studio floor or on small stages, Arnold would construct elaborate sets covered in fabric, paper, and found objects such as masks, jewelry, toys, bottle caps, coins, and shells. These repurposed parts proved the value and power of trash, of the discarded and meaningless, made into precious treasure through Arnold’s photography. In a fast and loose style, he would shoot participants in dynamic poses, framed by the assemblage display. Frequently, he would double- or triple-expose the images on the spot, feeding a photo back through the camera. The result was a magical complexity, patterns of radiant bric-a-brac emanating from bodies, sometimes naked or painted, sometimes costumed in various historical guises that corresponded with Arnold’s personal mythology.

Cultural and religious references are balanced by humor while the black-and-white palette evokes the glamour of old Hollywood, as well as the retrofuturism of mid-century sci-fi flicks. The result is something atemporal, a relic of the past with the innovation of the future.

Born in Oakland, Arnold took an early interest in art with his high school teacher Violet Chew playing a formative role. Here, he shared a special bond with Pandora, a collaborator for many years and a model in many of his photos. In the ‘60s, he studied at San Francisco Art Institute, and briefly attended École Des Beaux-Arts in Paris, but finding the curriculum to be suffocating and unnecessarily traditional he left to travel with friends to Formentera, an island off the coast of Spain, where they lived in caves and took LSD everyday, reveling in the freedom of wearing costumes and making art without the confines of formal education. The self-sabbatical renewed the artist’s passion for art-making and he returned to his studies back stateside.

While finishing his MFA at the San Francisco Art Institute, Arnold began Luminous Procuress, an ambitious film project which explored mind expansion and absurdity. The film’s narrative follows two free-spirited men who drink a magical potion and then proceed to hallucinate, complete with an array of odd clowns, queens, and mystics, accompanied by a soundscape that increases the overall eccentricity. The work won Arnold the 1972 New Director award at the San Francisco International Film Festival and led to an exhibition in New York at the Whitney Museum of Art.

In the early ‘70s Arnold introduced the world to the Cockettes, a famed group of glittery, gender-bending drag performers who became known for their midnight shows as a part of Arnold’s “Nocturnal Dream Show” at the Palace Theatre in San Francisco. The group was a precocious experiment in gender fluidity and non-binary presentation, and Arnold celebrated the idea that male and female are both part of the whole human experience, in each of us, like yin and yang. In interviews, he would often discuss the Zen teachings of Eastern philosophies, as well as the Native American idea of “two-spirits” and the synchronicity of Carl Jung’s concept of a collective unconscious.

While Arnold collected an impressive cast of personalities throughout his life from Timothy Leary to Tennessee Williams to Diana Vreeland, after Arnold contracted HIV, many people in his life abandoned him — though his close friendship with actress Ellen Burstyn, who features prominently in the documentary, endured until his untimely death. Even through his illness, Arnold continued to make art as long as he could, painting his final work in bed. After his death, longtime friend, Stephanie Farago, took charge of preserving his archive, and after her death in 2014, she entrusted his materials to her close friend Vishnu Dass, the film’s director.

Reorganizing the archive was a challenge; photographs, drawings, and props crammed into boxes, along with Arnold’s images of outcasts, of street vendors and hustlers, dressed as angels with massive feathered wings, ready to ascend to the heavens. These surviving artifacts remind us that art often lives on, longer than we do.