The City of Jakarta

It was on 1 October 1989, that I arrived in Jakarta (known as Batavia from 1619–1942) to start work as a young equity analyst for a British broking house in Indonesia’s newly deregulated capital markets. I had long had a desire to work in Indonesia having studied the Indonesian language for eight years at high school and university in my home town of Melbourne, Australia (1975–1983) and briefly at a university in Indonesia (1981–1982). Finally, I was working in Jakarta and I knew that I would use my spare time to immerse myself in Jakarta’s fascinating history.

Jakarta was officially founded in 1527 when Muslim forces loyal to the Sultanate of Bantam (now Banten) expelled Portuguese ships from the port of Sunda Kelapa and renamed it “Jayakarta”. Much of its first century is not well documented and it would not be until 1619 when Jayakarta came under the control of the Dutch East Indies Trading Company (the “VOC”) and it was renamed “Batavia”, that we start having detailed records of the city. Batavia/Jakarta was established to be both a show of force in the region by the VOC against competing Portuguese, British and Spanish interests and also as a port to serve as a base for supplying VOC ships and resting VOC merchants and sailors who plied the long but highly lucrative spice trade between Europe and the fabled Spice Islands of the Moluccas, particularly Banda, Tidore, Ternate and Ambon. It was the spice trade which funded the Dutch Golden Age of the seventeenth century and provided the wealth for many of Amsterdam’s leading merchant families to have their portraits painted by such great artists as Rembrandt and Frans Hals.

The VOC thrived for more than a century and Jakarta became one of Asia’s most important mercantile ports. The VOC built a fort and a walled city to keep out local rulers and their forces who wanted to expel the Dutch (but didn’t manage to do so). Canals were dug and Dutch-style houses built to give the city a flavour of home. Fortunes were made. The VOC reached the peak of its glory in the 1730s but then went into decades of decline caused by the collapse of spice prices, corruption, the rampant spread of disease and general inertia. The VOC’s charter was allowed to expire at the end of 1799 and from 1800, Jakarta came under the Dutch crown, notwithstanding several years of French rule during the Napoleonic era and five years of British rule of Java, under Lieutenant-Governor Thomas Stamford Raffles from 1811–1816. But from 1816, Jakarta was the capital of a clearly Dutch colony and no longer a company town as it had been under the VOC.

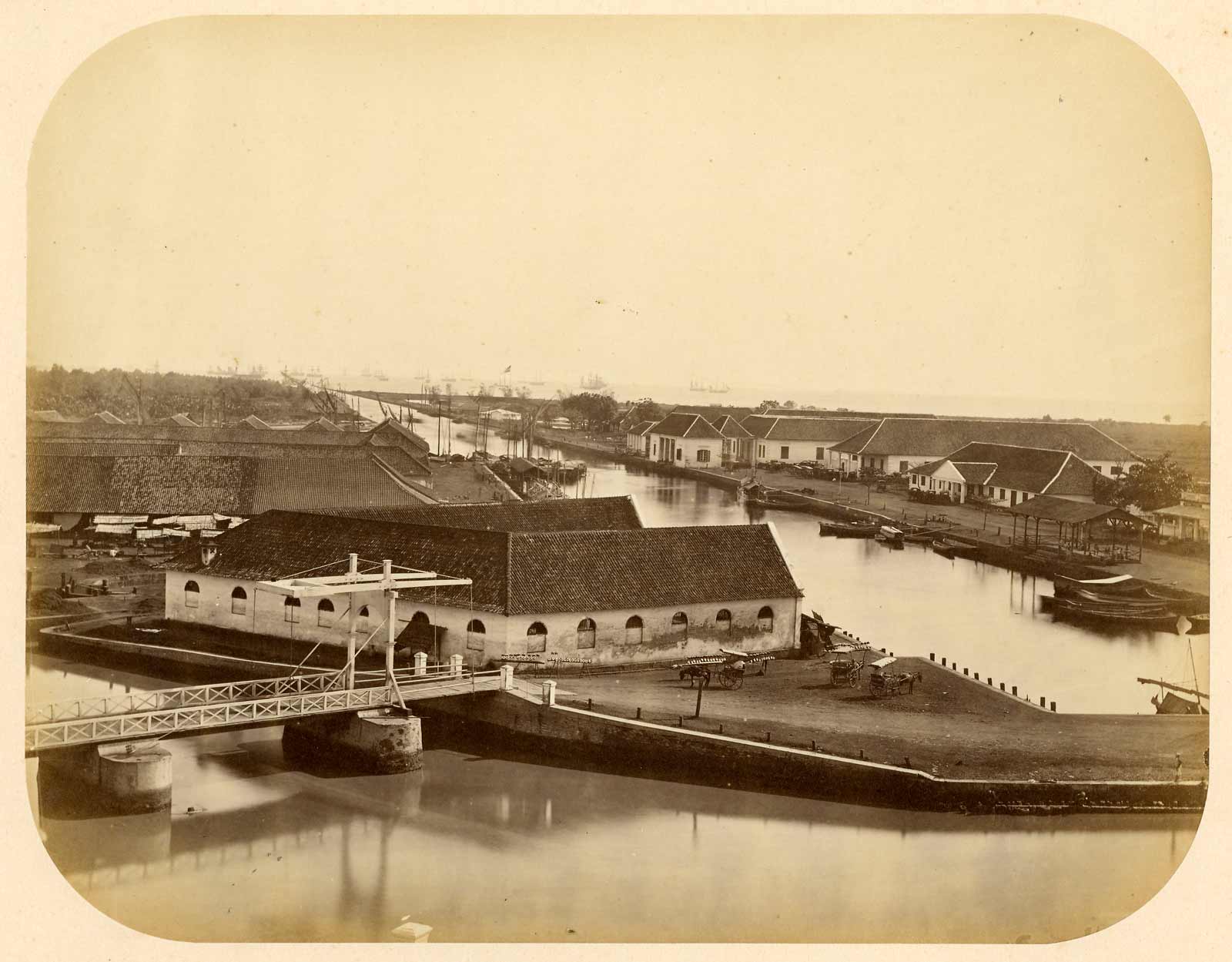

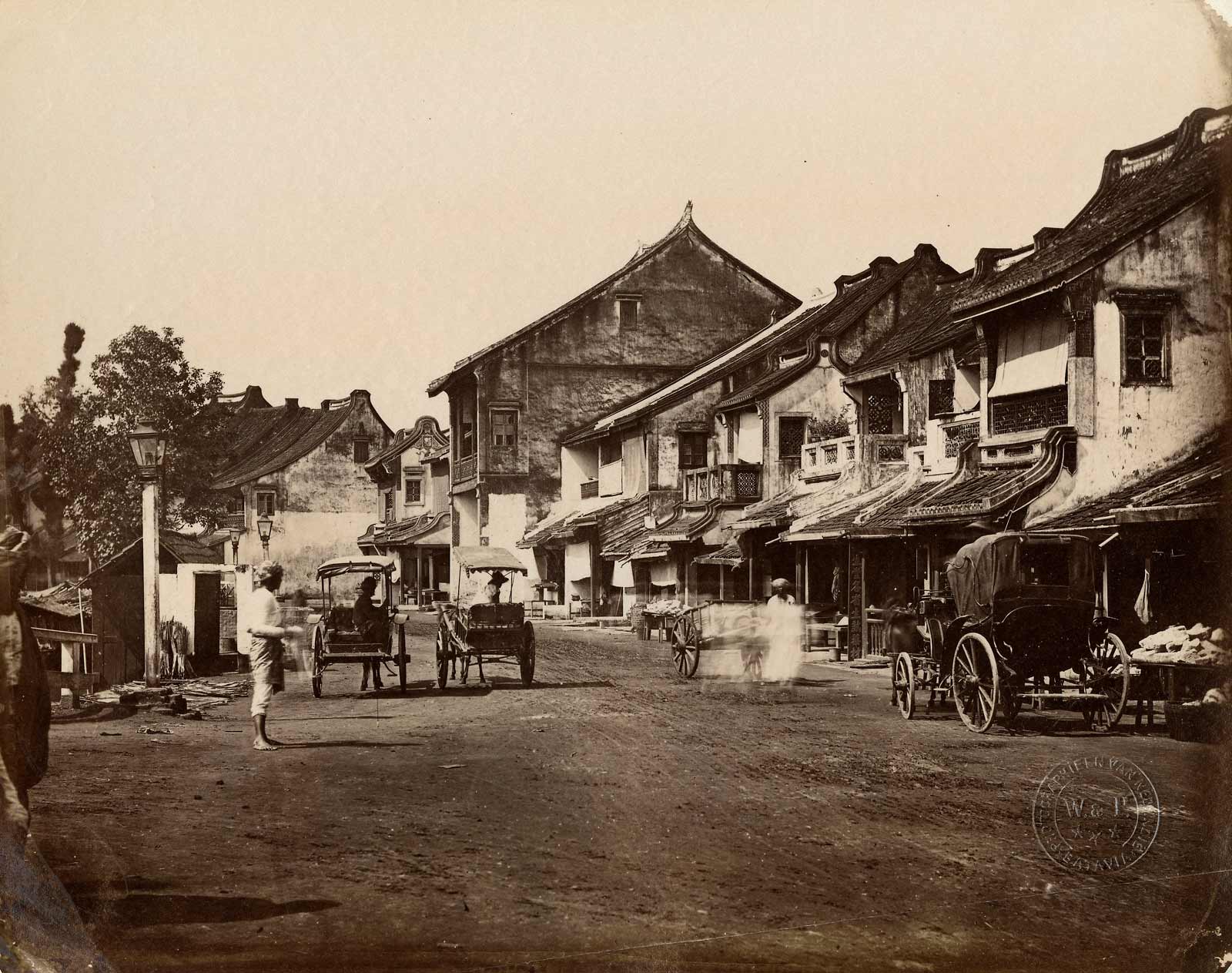

The VOC’s fort and most of the walled city were torn down in 1808 or 1809 but the old port (1) would continue to be the city’s main port until the mid-1880s. The old town also remained Jakarta’s central business district for European businesses (trading, banking, shipping and insurance etc.) until well into the twentieth century (2). A few reminders of the VOC era also survived such as the Amsterdam Gate (3). Adjoining the old town was the heart of Jakarta’s Chinatown and home to the dynamic and entrepreneurial Chinese population in a district still called “Glodok” to this day (4).

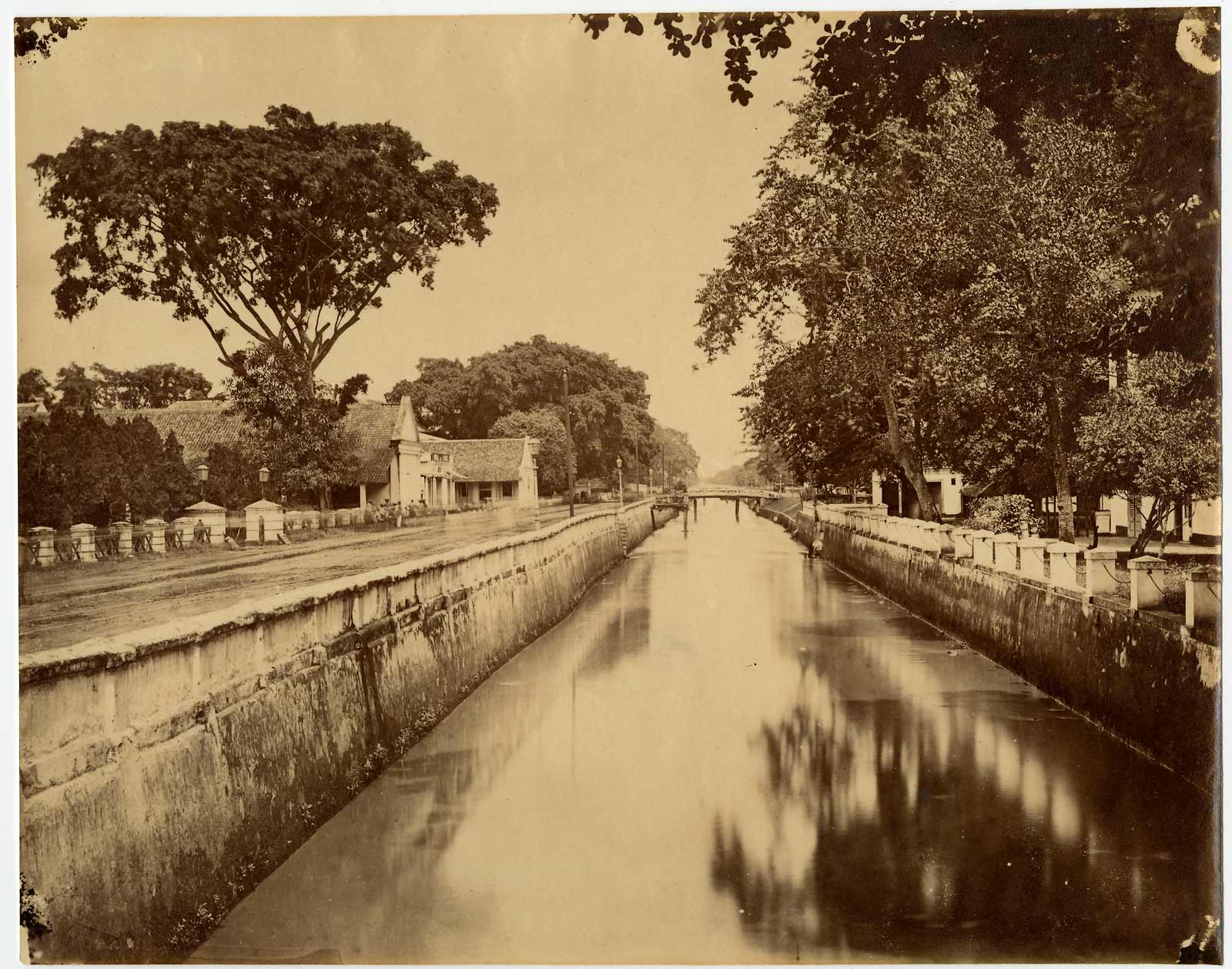

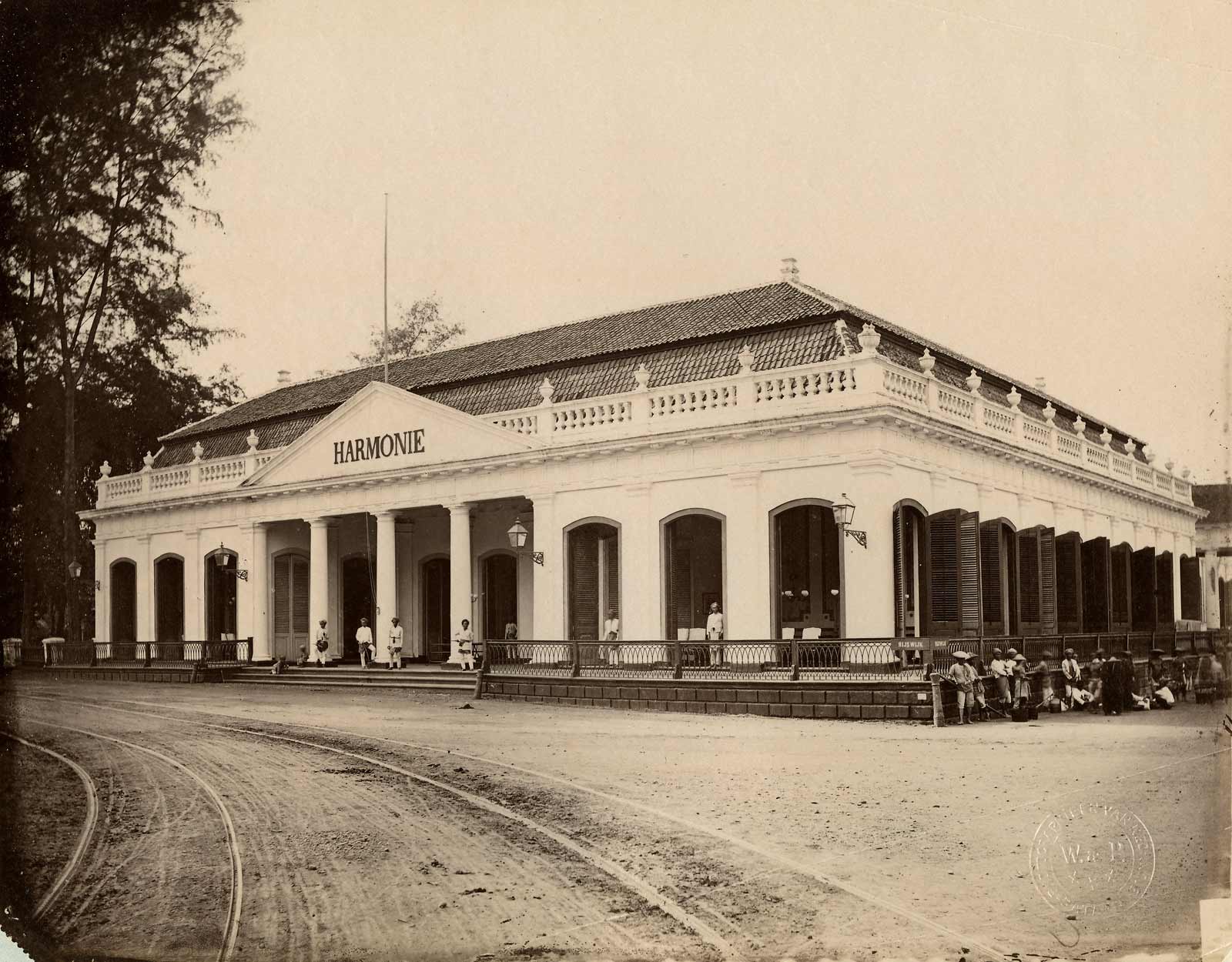

While the old town and port became the “downtown”, a new “uptown”, better known as “Weltevreden”, was built during the nineteenth century three kilometres south, typically at the end of another canal known as the “Molenvliet” (5). This was where the European population built their luxurious homes with large gardens (6), government buildings, churches (7), shops, hotels (8), social clubs (9) and even a theatre (10), a museum and a botanical & zoological gardens. It wasn’t only the Europeans moving to the south as the famous painter Raden Saleh (1811–1880) also built a magnificent and quite unique home for himself (11) which fortunately still exists today.

Visitors to Jakarta during the second half of the nineteenth century were often struck by the contrast between what they saw as the old and woefully inadequate port area and dark and somewhat rundown “downtown” business district in the north and the modern, elegant and resplendent new “uptown” district in the south.

The Arrival of Photography in Jakarta

Photography reached Jakarta during the first half of the 1840s in the persons of Jurriaan Munnich and Adolph Schaefer but the former is not believed to have been successful in his efforts, while the latter focused on Daguerreotype portraits (none of which are known to have survived) and images of Javanese antiquities and temples for the Dutch government (which are now the earliest surviving photographs ever taken in Indonesia). Other itinerant photographers passed through Indonesia in the early to mid-1850s but it was the arrival at Jakarta in 1857 of two young Englishmen Walter Bentley Woodbury (1834–1885) and James Page (1833?–1865) and the establishment of their photographic studio “Woodbury & Page” in Jakarta (12) in the same year, which marked the beginning of the creation of the greatest photographic record we have of the development of Jakarta during the second half of the nineteenth century.

Woodbury & Page would survive until 1908 (although its founders had ceased to be involved by 1864) and there can be no doubt that they were by far the most famous and important firm of commercial photographers in nineteenth century Indonesia. Without the many magnificent photographs of this firm, the photographic record of nineteenth century Jakarta, and indeed of many other parts of Indonesia, would be so poor as to be almost negligible, particularly between the 1860s and 1880s. But of course, they were not the only ones. There were other photographers also taking photographs of key buildings, landmarks, street scenes and monuments in Jakarta in the nineteenth century including Isidore van Kinsbergen (1821–1905), Jacobus Anthonie Meessen (1836–1885), Carl Kruger and the government’s own Netherlands Indies Topographic Bureau among others.

Collecting Nineteenth Century Photographs of Jakarta/Batavia

Since my teenage years, I have always been fascinated to seek out the earliest photographs of the cities I visited to understand what the cities used to look like and how they developed into what they are today. This was normally achieved through books. Naturally when I arrived in Jakarta in late 1989, I sought out books containing early photographs of the city. However, there were not many available. There was of course the classic Historical Sites of Jakarta, by the German Jesuit priest Adolf Heuken (first published in 1982 and reprinted many, many times since) and Jakarta: A History by Australian historian Susan Abeyasekere, both of which very influential for me (and Pastor Heuken became a great friend and mentor until his sad passing in 2019).

Other important books in my early days as a collector and researcher were Toekang Potret: 100 Years of Photography in the Dutch Indies 1839–1939 co-published in 1989 by the Museum of Ethnology in Rotterdam to accompany an exhibition held at that museum in that year, and Toward Independence: A Century of Indonesia Photographed, edited by Jane Levy Reed and published by the Friends of Photography in 1991 to accompany an exhibition in San Francisco (I was later able to acquire the Woodbury & Page photographs of Jakarta that appeared in the book and the exhibition). There were also two books by Dutch writer and photo-historian Rob Nieuwenhuys (1908–1999), Baren en oudgasten (1981) and Komen en blijven (1982) which focused on early photography in Indonesia between 1870 and 1920 and which were quite a revelation to me.

So I decided to start my own collection of early photographs of Jakarta and through the photographs build my own “time machine” that would take me back to the nineteenth century and help me understand how the city of Jakarta evolved and developed. It would be an exercise in “urban archaeology” and allow me to recreate Jakarta as it once was. My first purchase in around 1991, and found completely by chance, were four albumen prints depicting scenes from “downtown” Jakarta and the old port by a (still) unknown photographer circa the 1890s from an antique dealer in Singapore. I was captivated by them and knew that this would be the beginning of an exciting journey.

1994 was a very pivotal year for me as a collector for more reasons than one. During that year, I came across a Swann Galleries of New York catalogue from one of their photograph auctions of 1993. In it there was an early album of photographs of Jakarta by Woodbury & Page dating back to the first half of the 1860s. Kicking myself that I thought I had been too late and missed the chance to buy it, I wanted to find out the price it had sold for only to discover that it had been passed-in on the day of the sale. So did I perhaps still have a chance to acquire it? I contacted Daile Kaplan at Swann Galleries and she very kindly put me in touch with the owner of the lot and I was able to negotiate a purchase of the album directly from him (of course paying the appropriate commission to Swann Galleries as well). What a thrill that first major purchase was for a young collector.

Also in 1994 in June, I was in the Netherlands and visited the antiquarian book dealer and art historian, Leo Haks, in Amsterdam, who I had first met in Jakarta in 1990 or 1991 and purchased from him another Woodbury & Page album containing many outstanding images showing excellent sharpness and tonality (further purchases from Leo would follow in October that year).

While still in Amsterdam on that trip, Leo also told me that a comprehensive book about Woodbury & Page by Steven Wachlin entitled Woodbury & Page: Photographers Java had just been published by the KITLV (Royal Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies) in Leiden and that the KITLV were simultaneously holding an exhibition of Woodbury & Page photographs from their vast collection. I naturally rushed out to Leiden and was enthralled by the exhibition and the book. Both Leo Haks and Steven Wachlin subsequently became great friends and mentors for me as a collector and as a researcher.

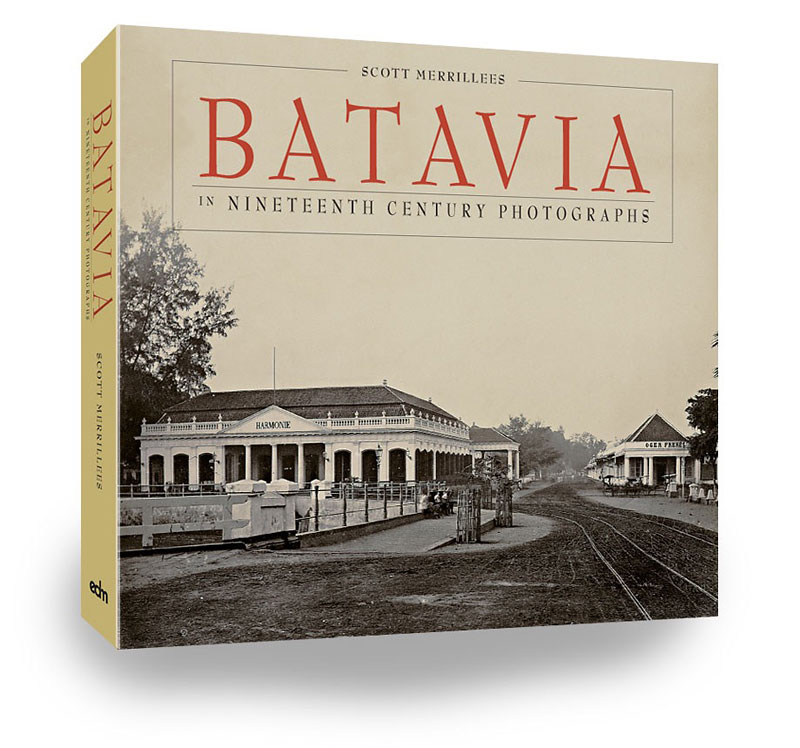

It was also in 1994 that Leo Haks planted in my mind the idea that as I was both keenly collecting and avidly researching, that I should write a book to bring the Jakarta of the nineteenth century to a wider audience. A six-year journey thus began which culminated in the publication of BATAVIA in Nineteenth Century Photographs in 2000. It was also Leo Haks who introduced me to my first publisher (Editions Didier Millet) and who introduced me to Dutch institutes, libraries and museums which had important collections of nineteenth century photographs of Indonesia which we visited together in Amsterdam, Rotterdam and The Hague.

My collection grew while I was researching and writing and important finds were made at auction houses large and small in the Netherlands, England, Germany, the USA and Singapore and from dealers in the Netherlands, France and the USA.

Thanks to the kindness of Steven Wachlin, I was introduced by mail and email to Miss Luanne Woodbury in London, the sole surviving granddaughter of Albert Woodbury (1840–1900) who had very successfully run the Woodbury & Page studio in Jakarta from 1870 until the early 1880s. Miss Woodbury had just inherited from her late sister, eleven Woodbury & Page photographs, including a spectacular interior view of the Woodbury & Page studio from the time that her grandfather was the proprietor. I was able to purchase those photographs from Miss Woodbury just in time to include them in my book. A great thrill indeed. It was quite moving later when Miss Woodbury told me that she had used some of the proceeds from the sale of the photographs to me to have a new headstone made for Walter Woodbury (who had sadly died in poverty) at the Abney Park cemetery in London where Walter had been buried in 1885. I was finally able to meet Miss Woodbury for the first time in 2012 or 2013 in London by which time she was already in her 90s.

Collecting and researching nineteenth century photographs of Jakarta can have its dangerous moments as well. For most of the 1990s, my collection was kept at our home just outside Jakarta. But during the riots in Jakarta in May 1998, the shopping mall in our housing estate was set on fire and rioters also started moving towards the housing area as well on the same evening but fortunately stopped before entering. As a precaution the following morning, I wanted to take my collection to my office in Central Jakarta for safety but to do so meant driving through the streets of Jakarta where crowds were still rioting and looting, with the risk that my car would be stopped. Fortunately, I safely made it to the office.

After the publication of BATAVIA in Nineteenth Century Photographs in 2000, of course collecting and research continued. Very important acquisitions were made in Germany in 2007 and in the Netherlands in 2012, and so hopefully a fully revised edition of the book can eventually be realized. Research possibilities have also been greatly improved with the arrival of the internet era and all the access to digitised Dutch archived that this brings.

Scott Merrillees (1962) was born in Melbourne, Australia, and graduated with a Bachelor of Commerce degree from the University of Melbourne in 1984, with majors in accounting and Indonesian studies. He learned the Indonesian language at high school and university in Australia (1975-1983) and at Satya Wacana Christian University in Salatiga, Central Java, Indonesia (1981-1982). He has worked in Jakarta for more than twenty-five years in equity research, capital markets, banking, mining and healthcare.

Scott has collected and researched pre-1942 photographs and postcards of Indonesia for thirty years and he is best known for his three books on the history and development of Jakarta from the middle of the nineteenth century: BATAVIA in Nineteenth Century Photographs (published in 2000 and reprinted in 2001, 2004, 2006 and 2010), Greetings from JAKARTA: Postcards of a Capital 1900-1950 (published in 2012 and reprinted in 2013 and 2019, and also a Dutch language edition in 2012) and JAKARTA: Portraits of a Capital 1950-1980 (published in 2015). His forthcoming book FACES OF INDONESIA: 500 Postcards 1900-1945 is his first book to focus exclusively on the people of Indonesia and how they were represented during the last half century before independence.

Scott married Theresia in Jakarta in 1992 and they have two children, Maxi and Nicole, who were both born and baptised in Jakarta. He can be contacted at: Contact.

His website is: scottmerrillees.com

All images from author’s private collection, copyright Scott Merrillees.