When Saul Leiter passed away at age 89 in November 2013, he left behind two East Village apartments bursting with artifacts from his long, productive, art-filled life. There were lithographs and prints by some of his favorite artists; thousands of books of all kinds, many bearing a 49-cent sticker from the nearby Strand Book Store; pieces of beautiful old furniture hidden from view for decades, frequently branded with absentminded cigarette burns; funny, ancient-looking toys and tchotchkes; antique kitchenware ready to be dusted off and sent back out for duty; dozens of little straw brooms once used to sweep the parquet floors.

Mainly, though, there was the archeological treasure waiting to be mined by the Saul Leiter Foundation—thousands and thousands of pieces of Saul’s own work: negatives, slides, undeveloped rolls of film; paintings, many looking ready to turn to dust at the slightest agitation; painted photographs, often tucked into books on the shelf like the world’s most precious bookmarks; and, of course, photographic prints of all sizes, in color and black and white. Margit Erb, the director of the foundation (and my wife), enlisted a small team to organize the prints into archival boxes, and years of cataloging began, an effort that we continue to this day.

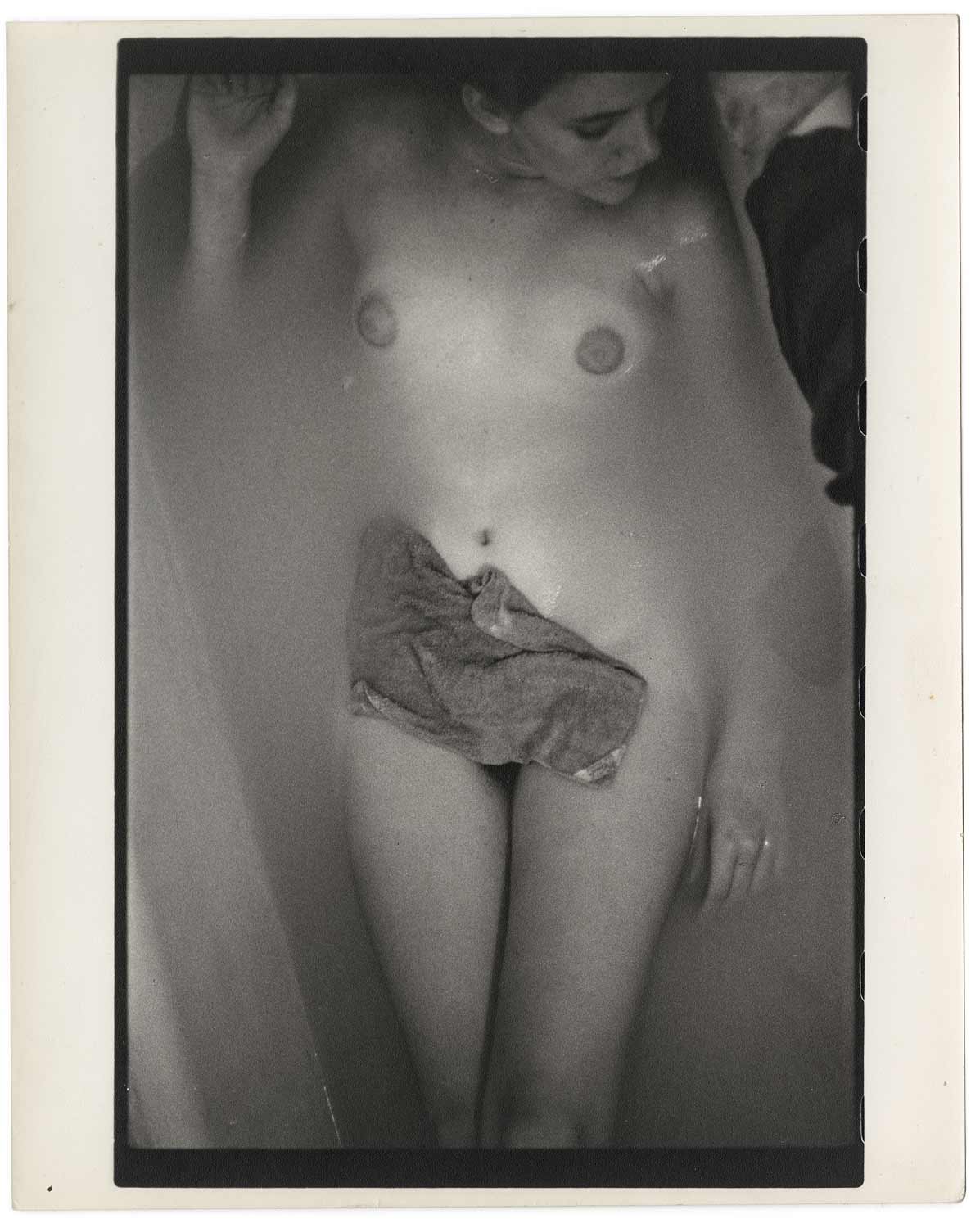

Among the street photography, the portraits, and the fashion work, we were surprised to find such a vast number of printed nudes—several thousands, in fact. The extremely pleasant task of cataloging them then fell on me, and, since most of the prints had never been seen, I embarked on a journey into a heretofore-private world of Leiter’s friends and lovers. What I found is a deeply moving, highly personal body of work that adds a new voice to the conversation on the nude that began immediately after the invention of photography in the early nineteenth century.

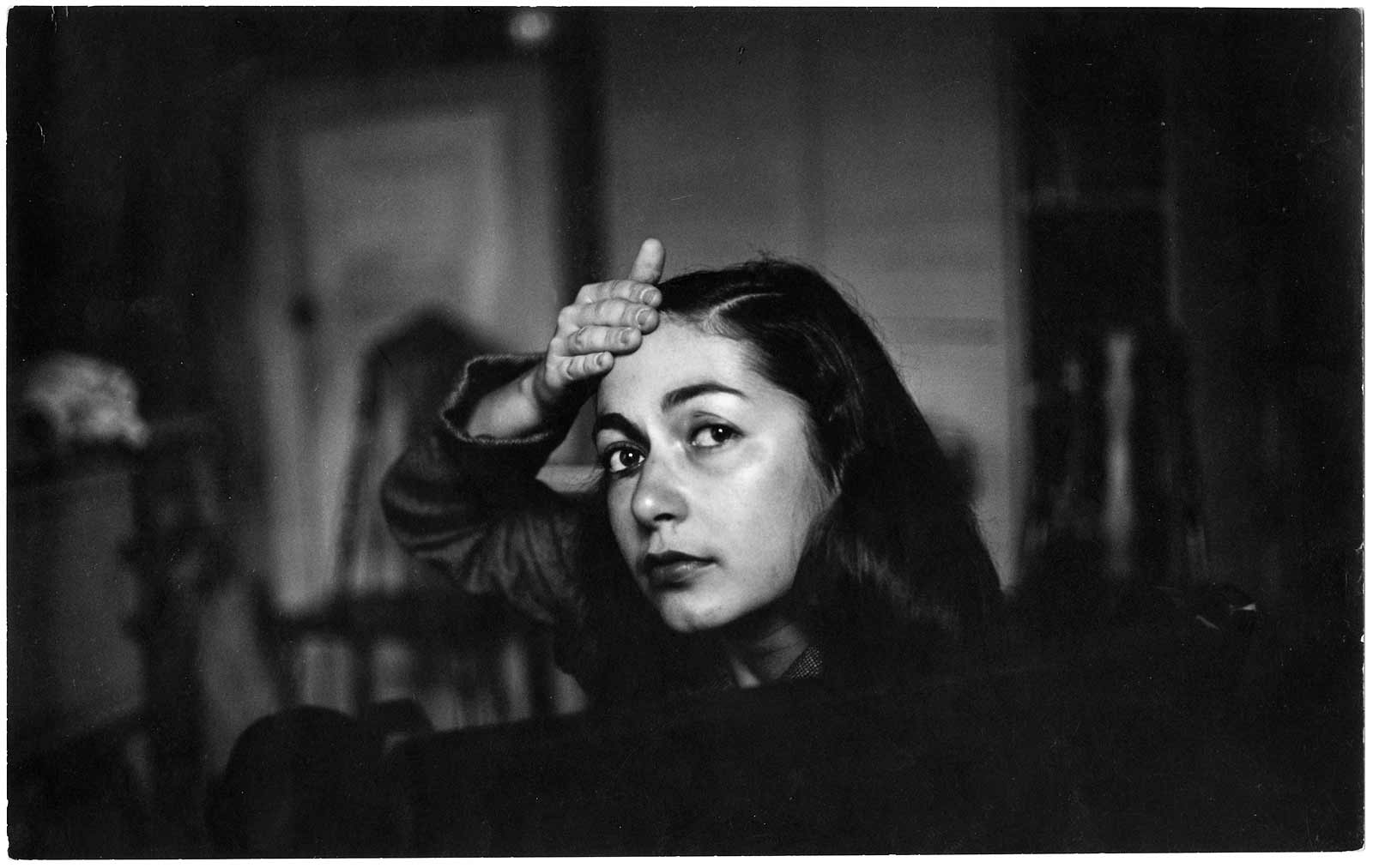

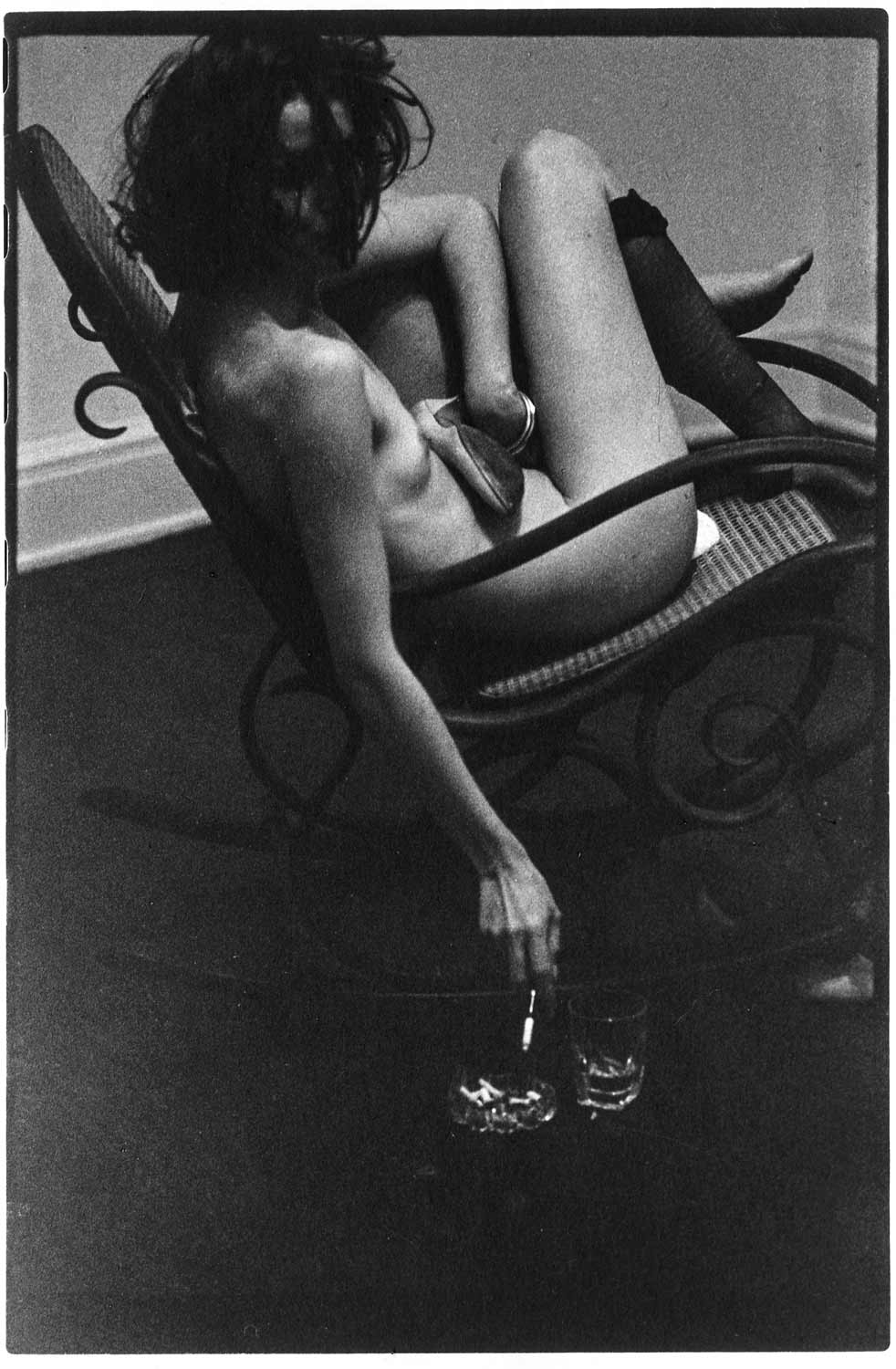

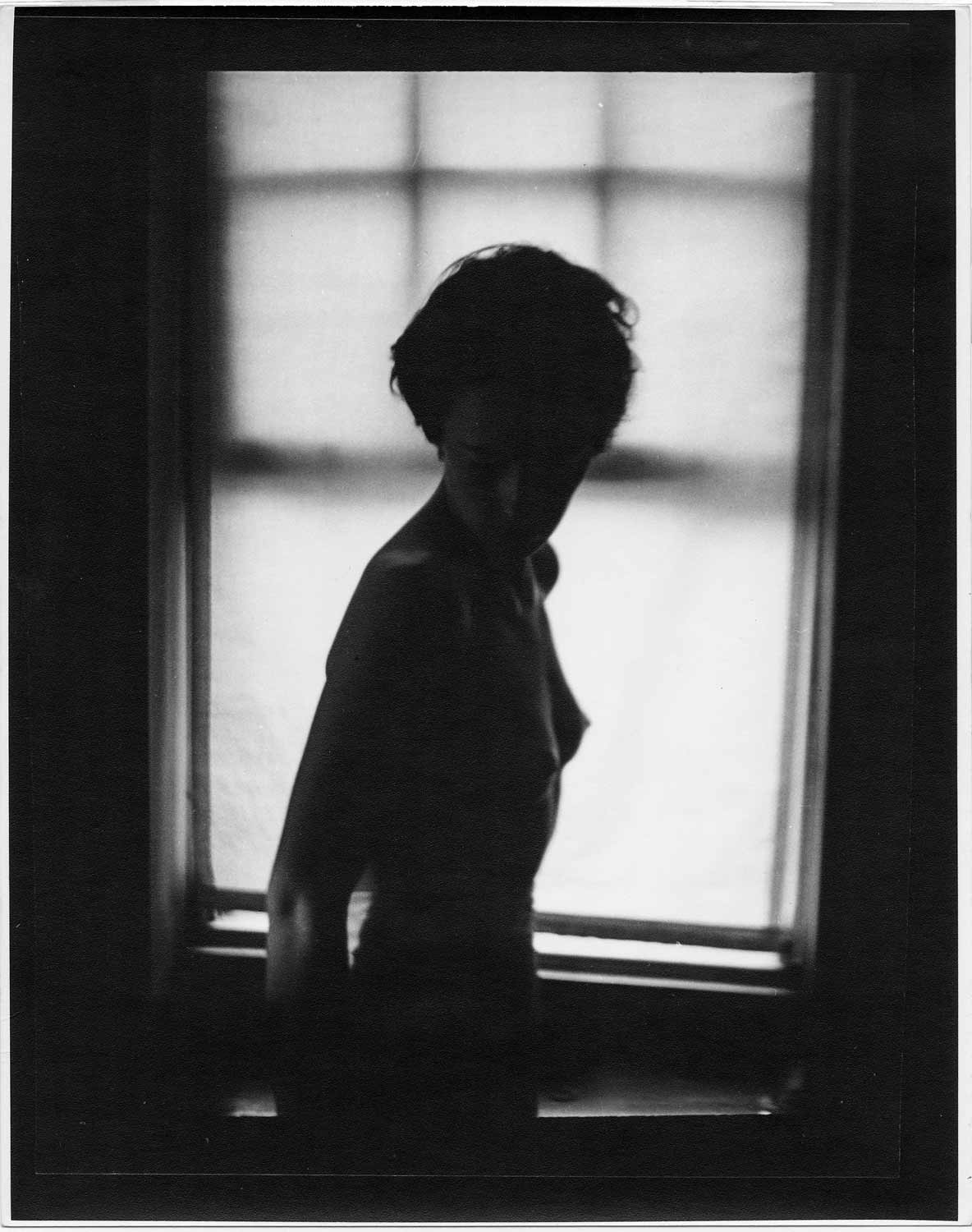

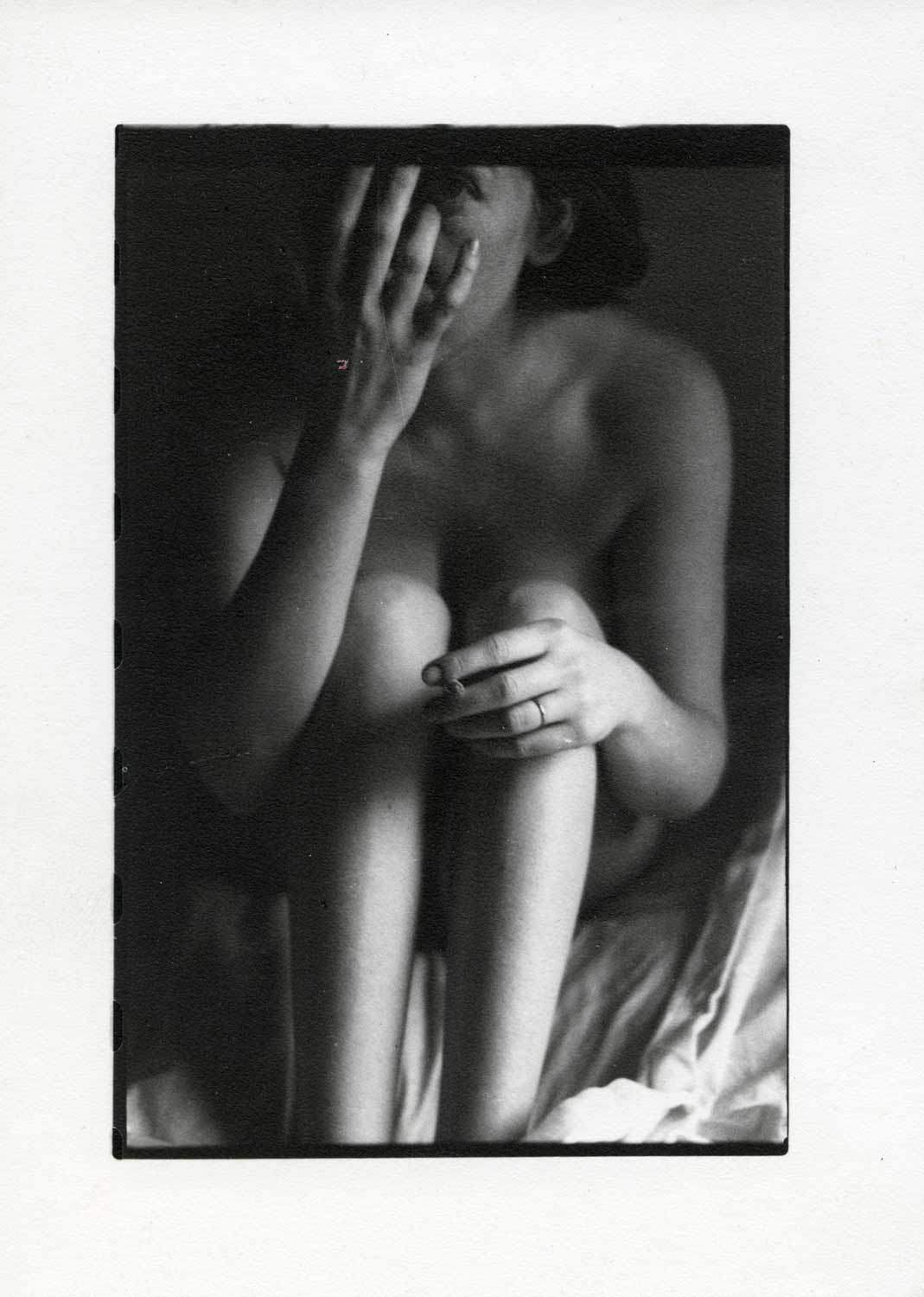

In his nudes and intimate interior portraits, most of which were taken between the late 1940s and early 1980s, Saul isn’t concerned with the human body nearly as much as he is concerned with humanity. He hardly ever focuses on a woman’s form as if it’s a landscape, thus fragmenting the figure as photographers such as Ralph Gibson or Eikoh Hosoe do; he usually shows the whole person, full of life, even when he’s playing a game of hide-and-seek by placing another object in the foreground of the frame. Some details in the photos place them at mid-twentieth-century, while others are timeless. An untitled triptych captured circa 1947, for instance, could have been taken yesterday.

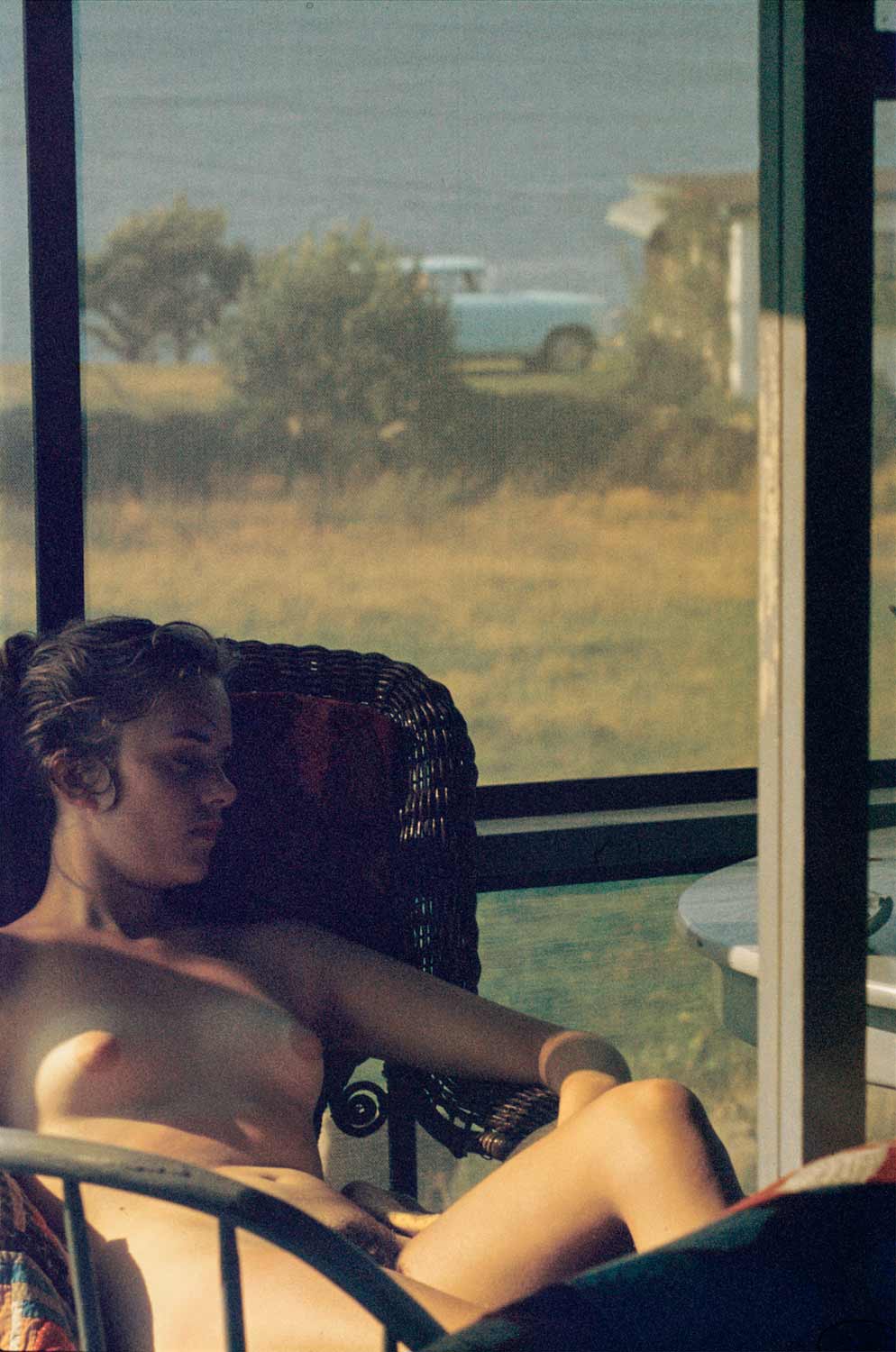

Unlike his other photography and the majority of his vast output as a painter, Leiter’s nudes don’t deal very often in abstraction; they are rarely marked by the kind of visual confusion Saul loved so much, where at first you’re not sure what you’re looking at. Clearly he felt that this side of his art required a different set of parameters. And besides the famous “Lanesville” (1958) and its variants, very few of his nudes are in color, which means that in the ’50s, as he was walking around his neighborhood every day and breaking new ground in color photography, Saul was shooting in black and white once he returned home to his apartment.

The individuality of the women in these pictures is almost never obscured, which helps explain what makes Leiter’s nude photography so distinctive. The artist’s effortless sense of intimacy closes the gap between photographer and subject. That’s one reason why it was so fascinating for me to catalog his nudes—I was getting acquainted with beautiful pictures, but I was also getting to know beautiful, multifaceted people, most of whom appear in multiple images captured on different days.

The women in the photos are collaborators—conspirators—sharing with the photographer intimate moments that will be preserved in gelatin silver. Saul and his subjects are playing, romping, having a good time together. As each woman lets her guard down, revealing her true self, she reflects the trust she has in Saul.

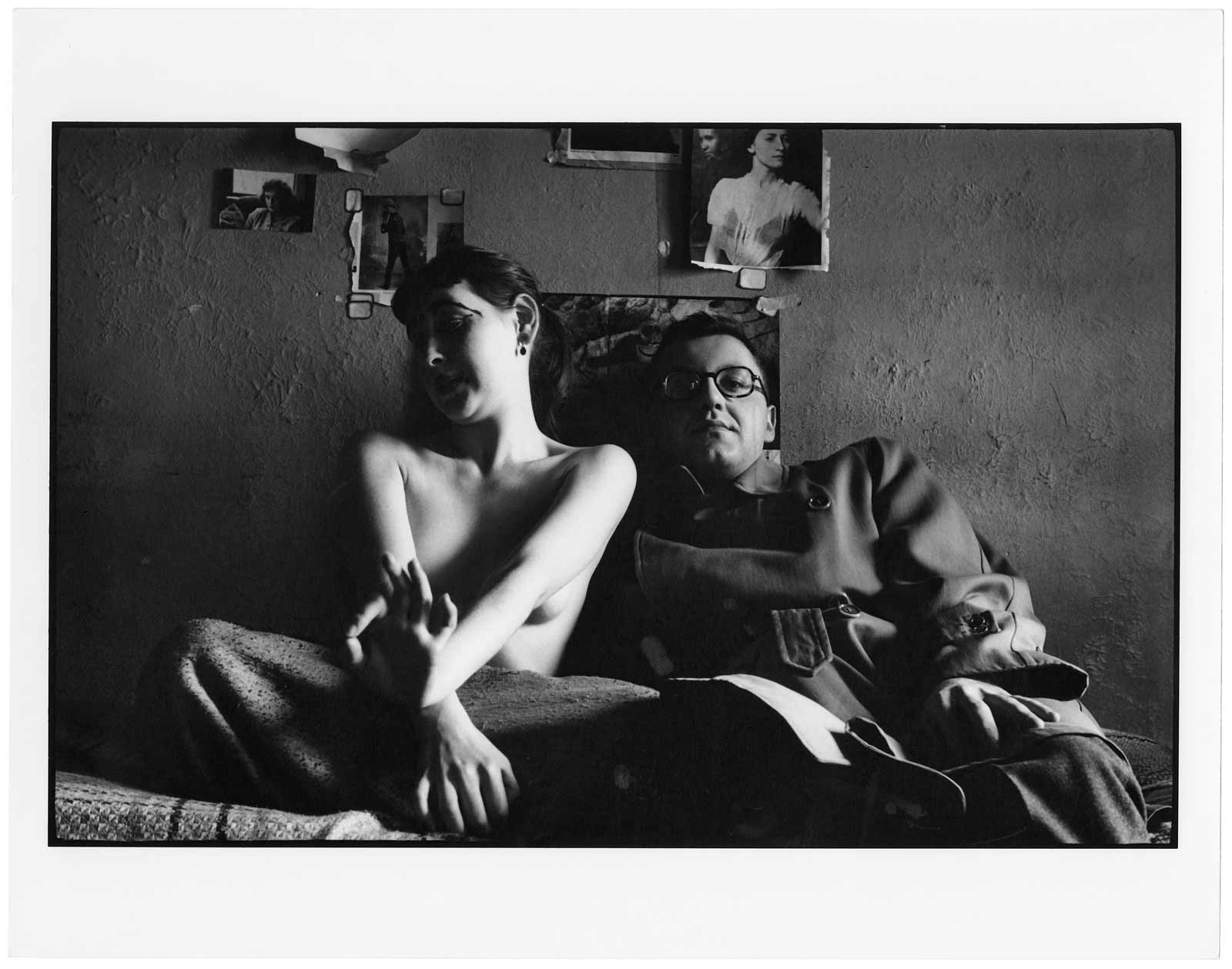

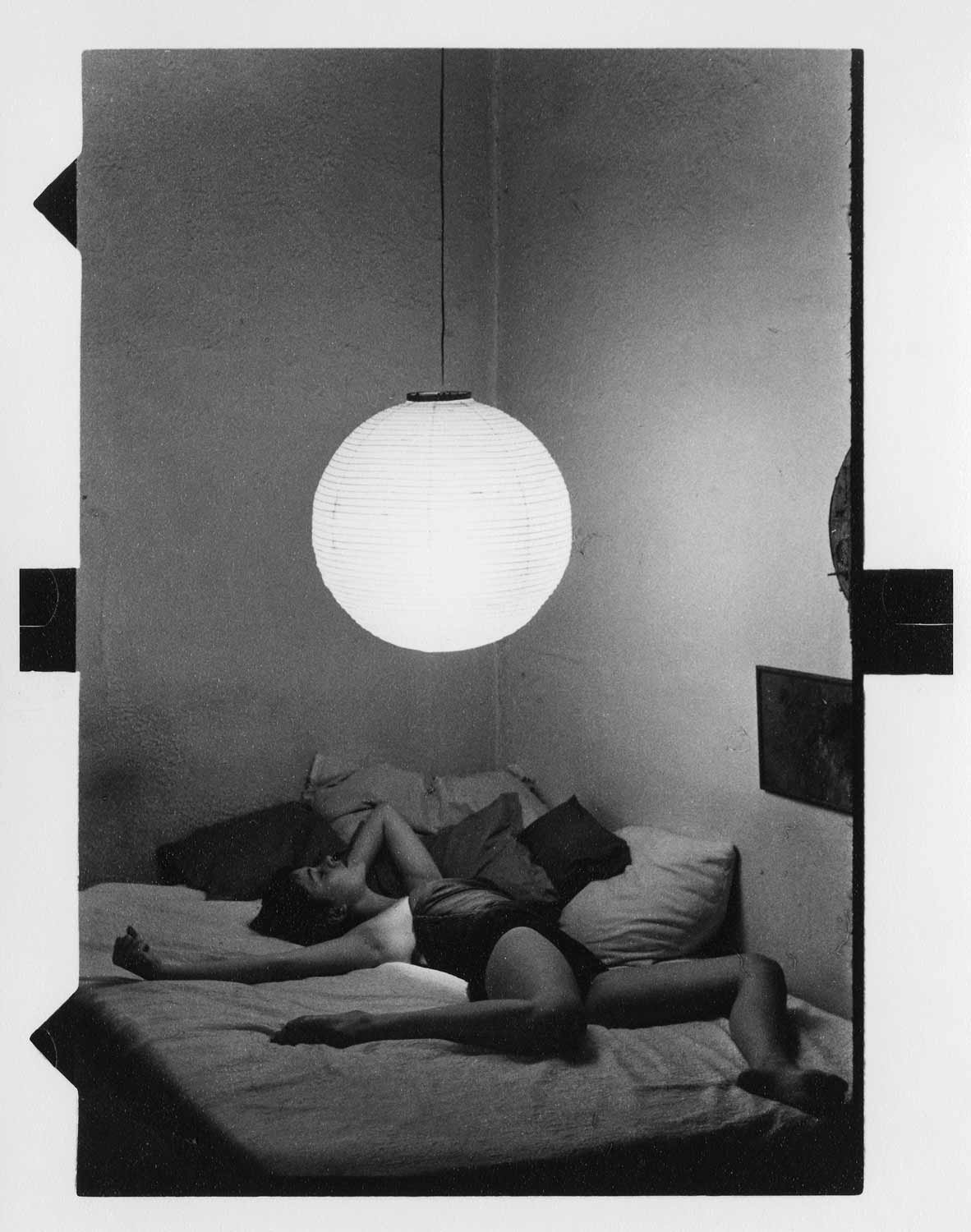

Leiter would undoubtedly agree with Harry Callahan, famous for his nude images of his wife, Eleanor, who says in Lustrum’s 1979 book Nude: Theory, “I wanted to photograph the person for whom I had feeling. It wasn’t enough just [to] photograph a nude.” We can see in many of Saul’s nudes that he’s simply lounging around the apartment with one of his subjects (he lived with one or another of them at various points), taking pictures while going about daily domestic life, away from the time constraints and potential awkwardness of working with an unknown model. As Kenneth Josephson says in Nude: Theory, “With a hired model you might do a lot of work all at once. When you are photographing a wife or a friend, the work usually extends over a period of time. Also, you are in a position to observe interesting things when you are around a person in a day-to-day living situation. You can enlarge on the observation photographically.”

Indeed, Leiter was a bit of a homebody, and his observations often convey the stillness and quiet of an ordinary afternoon at home. You can smell the cigarette smoke, hear the classical music playing on the radio. The women in his pictures look comfortable, sometimes sleepy, in their (usually quite natural) poses. The bedsheets are inviting indeed. Saul is conveying a kind of simple realism, but with his typical eye for unique composition. Like most of his art, his nudes, without sidestepping a range of moods, have a consonance, a beauty. Yet he doesn’t idealize his subjects or shy away from revealing complex emotion. In fact, one of the primary colors in his nudes is sadness.

The Joys of Experimentation

To see his nudes, which have been collected the books In My Room (Steidl, 2018) and Women (Space Shower, 2018), among others, is to understand that Saul Leiter loved women. And it seems pretty clear that women loved him. In the pictures, the camaraderie is unmistakable—you can sense it in the way artist meets subject on equal footing. When they’re feeling sexy, a slow-burning sensuousness graces the image; other times a little mischief, or humor, seeps in. Saul was a skillful printer of his own black-and-white work, and he printed many of these photographs multiple times, in different sizes and with varying contrast.

As tempting as it is to view some of this work as a rebellion against the religious life that his rabbi father envisioned for him, the rejection of which led to a permanent rift in his family, Saul did not take nudes in order to rebel. He took nudes to have fun, to blow off steam, to scheme artfully with his friends—to produce interesting and lovely images, which he prized above all. Saul’s true rebellion was to seek freedom from the constraints of the life that had been decided for him. These photographic experiments were something else, pushed along by the fast-flowing river of the Abstract Expressionist scene he was swept up in after moving to New York in 1946—a burst of inspiration upon finding like-minded artists to spur his developments—rather than a reaction to an upbringing where the idea of a career in the arts was unthinkable. Leiter was engulfed by the downtown Manhattan current yet had a sturdy branch to hold on to: his belief in what he saw and how to share it.

Some of these women were Saul’s lovers. We know details about many of them, but not nearly all of them. For ages Saul wouldn’t reveal to us who any of the women were. Sometimes he wrote deliberately misleading information on the back of his prints and paintings. In his slashing, looping, one-of-a-kind handwriting he’d add “young musician” for a woman who, we suspect, hardly picked up an instrument; “Akira, Tokyo” when his subject, like Saul, had never even visited Japan; and “landlady’s daughter” for a person whose mother didn’t rent an apartment to anybody, least of all to Saul.

I think he was toying with convention when he did this. He was trying out things that his heroes had done, but in his own way, which goes double for the work itself. Saul was sweetly, casually (and sometimes archly) contrarian; he was just different. It’s clear that as he pored over his own work—made notes on it, left red herrings and perhaps a few bold revelations—he was thinking about other people looking at it, cataloging it. Even decades ago, in the depths of the poverty and obscurity that followed his sudden late-’70s abandonment of his highly regarded fashion career, he knew his art would someday be seen.

Although they feature some lightly prearranged settings—a few key props, like a scarf or a newspaper—Saul’s nude photographs share his straightforward overall philosophy of “I see something, I take a picture.” He’s sharing with us a moment he finds pleasing or compelling, but he’s not interested in making a statement beyond that. How deep we go, how much we read into his images—that’s up to us. Sometimes I think he’s daring us to go as deep as he’s gone in life, to see as deeply as he sees.

In Taschen’s 1995 book 1000 Nudes: A History of Erotic Photography from 1839–1939, which covers the period ending just before Leiter’s first attempts in the field, around 1947, Michael Koetzle writes, “The earliest nude photographers… were painters or lithographers who turned to photography [in part] because the new pictorial medium held such fascination. Their nude studies ally the joys of experimentation with a marked feeling for pictorial effects, for natural poses and decors, for composition and lighting, which was also based on an intellectual interest.” Much of this could describe Leiter, except that Saul, though undoubtedly an intellectual, was visceral in his work, even hedonistic—in his gentle way—and staunchly refused to dwell on any type of intellectual interpretation, or elaborate on the intention behind his art. His outlook was perhaps the inverse of that of Michals, who says in Nude: Theory, “My mind is always the source of my work, never my eyes.” Leiter led with his eyes.

It was likely his eyes that drew him to Soames Bantry, a model and fellow artist with whom Leiter shared his life for nearly 50 years before her death in 2002. (Saul often expressed regret that Soames was unable to share in the late-career success he enjoyed following Steidl’s 2006 publication of Early Color.) In many ways his longtime partner, who appears in dozens of his nudes, was his most artificial subject and his most real. She mugs, she pouts. She hams it up for the camera far more than the other women yet can never hide her vulnerability. Her feelings of insecurity are palpable. A subject of some of Saul’s best fashion images, in magazines such as Esquire and Harper’s Bazaar, Soames found an assuredness in a commercial shoot that she couldn’t muster at home, for whatever reasons. This helps make her so riveting.

In this body of work Bantry is unique because her life with Leiter has been documented—Saul talked about her frequently and wrote about her in Kehrer’s 2012 book Saul Leiter: Retrospektive, and Margit knew her well—while some of the other subjects are lesser known. Of course, now, after spending so much time with the women in his photographs, I have a thousand questions that I wish I could ask Saul. He’d probably answer them with a thousand of his own.

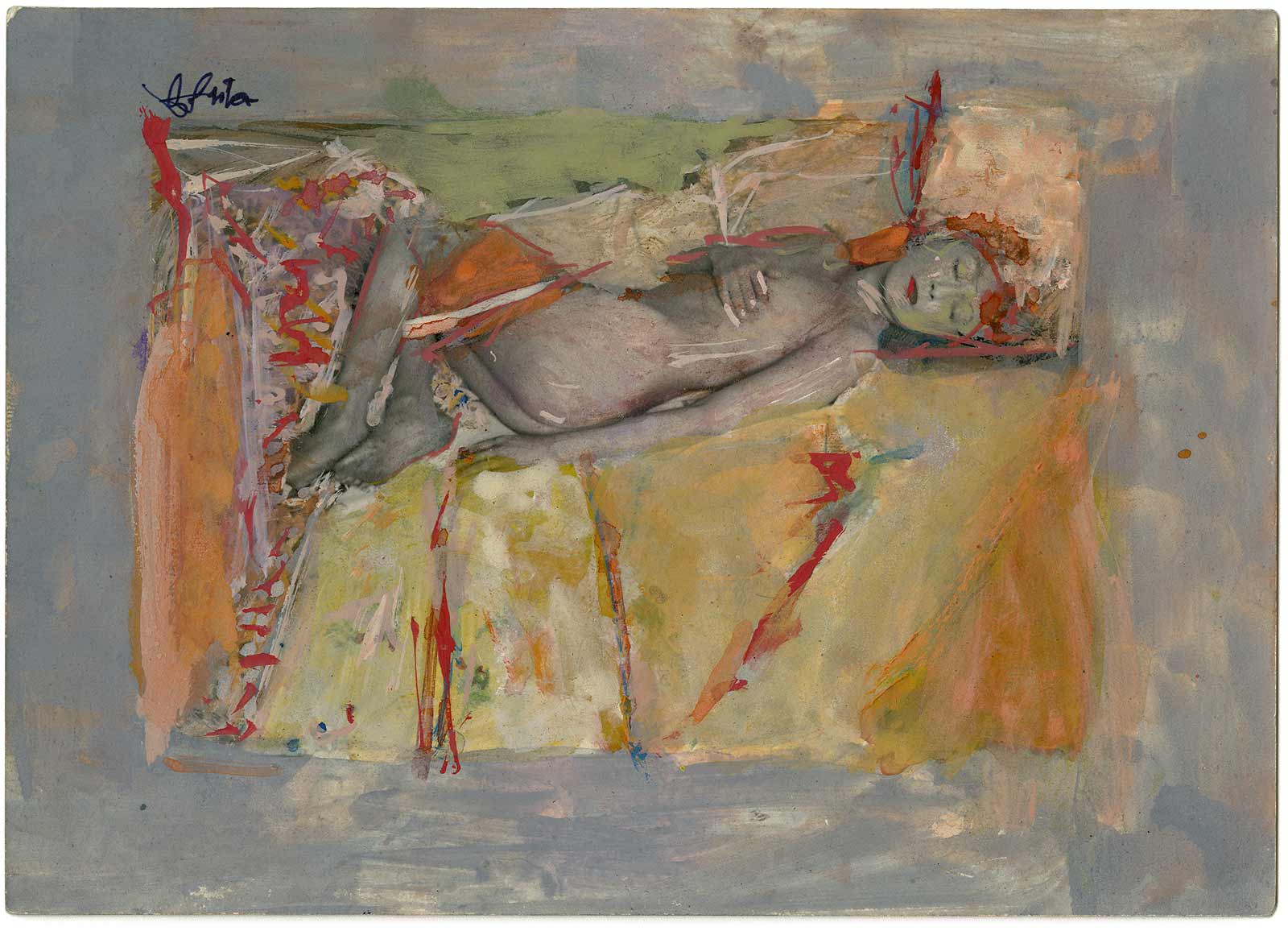

Painting Pictures

In his leanest years, the late ’70s through the early ’90s, Saul sat by his huge garden-view window under the lush northern light, painting. (Drips and streaks of color remain on his bench decades later.) And this is where the story of his nudes takes on an inspired twist: He turned to his own photographs for comfort, at the same time discovering an important new focus in his art—the painted nude. In applying acrylic paint atop the prints he’d made, he found a project that gave him solace during a dark time and produced hundreds of delights. Beyond a self-portrait with an added swath of green; a paint-swirled picture of his dear friend Henry Wolf, the magazine editor who first envisioned a book of his nudes; and his shot of a young coffee-drinking Andy Warhol adorned with fittingly brash strokes of red and purple, Leiter painted primarily on his nudes. These works marry Saul’s colorful, abstract painting style to his visionary photography, and there is nothing else in his oeuvre quite like them. They bring out new dimensions of the subjects themselves; in some of the most effective examples the women remain identifiable from Saul’s unpainted nudes yet, with a stroke here, a scratch of the brush there, become different people entirely.

In hindsight, some sort of union between painting and photography was inevitable in Leiter’s work. Given his trenchant explorations in both fields, plus his bold imagination, how could it not be? Though he often told us that he felt no need to choose between them, Saul considered himself a painter first and then a photographer.

Leiter had great admiration for Degas, an early example of the painter/photographer; the French Impressionist’s landscape paintings helped inspire some of Saul’s hillside-evoking abstract acrylic works. Tellingly, Degas’ 1895 photograph “Seated Nude,” with its glimpse of everyday life and natural indoor setting, could practically pass for a Leiter.

Similarly, Saul shot a handful of bathtub nudes, in something of an homage to paintings by perhaps his very favorite artist, Bonnard. Completing the circle, Bonnard’s photograph “Model Taking Off Her Blouse in Bonnard’s Paris Studio” (c. 1916), with its mirrored profile of the subject in contrast to her direct gaze in the foreground, makes use of what would years later become one of Saul’s most trusty photographic motifs, the reflection, employed regularly in his nudes and his street photography alike.

Lost and Found

Leiter devoted his life to his art, yet people mattered to him. Although he and Soames disappeared from view for long stretches, Saul was actually very sociable. He laughed easily and often, and could be a relentless inquisitor, fueled by an insatiable curiosity as much in conversation as in his creative pursuits or his autodidactic dives into the depths of art history. In the field of intimate portraits he discovered a way for his loved ones, including his beloved sister, Deborah, who was the subject of many of his very first photographs, to join him in his aesthetic explorations, as organically as whiling away a few hours at home.

I think that in his various creative endeavors Saul was buoyed by the idea of someday standing alongside his heroes. He certainly knew that his talent made this possible. Yet his black-and-white nudes and painted photographs, only a few of which were sold in his lifetime, remained his gift to himself. Now, happily, they’re his gift to the world. Those of us who knew Saul well understood that he made sacrifices in his life—his family, his commercial career, a reliable income. The two constants for him were taking pictures and painting. Saul lost a lot during his nearly 90 years on Earth, but he found a lot too. I’m pretty sure of one thing: He believed it was worth it.