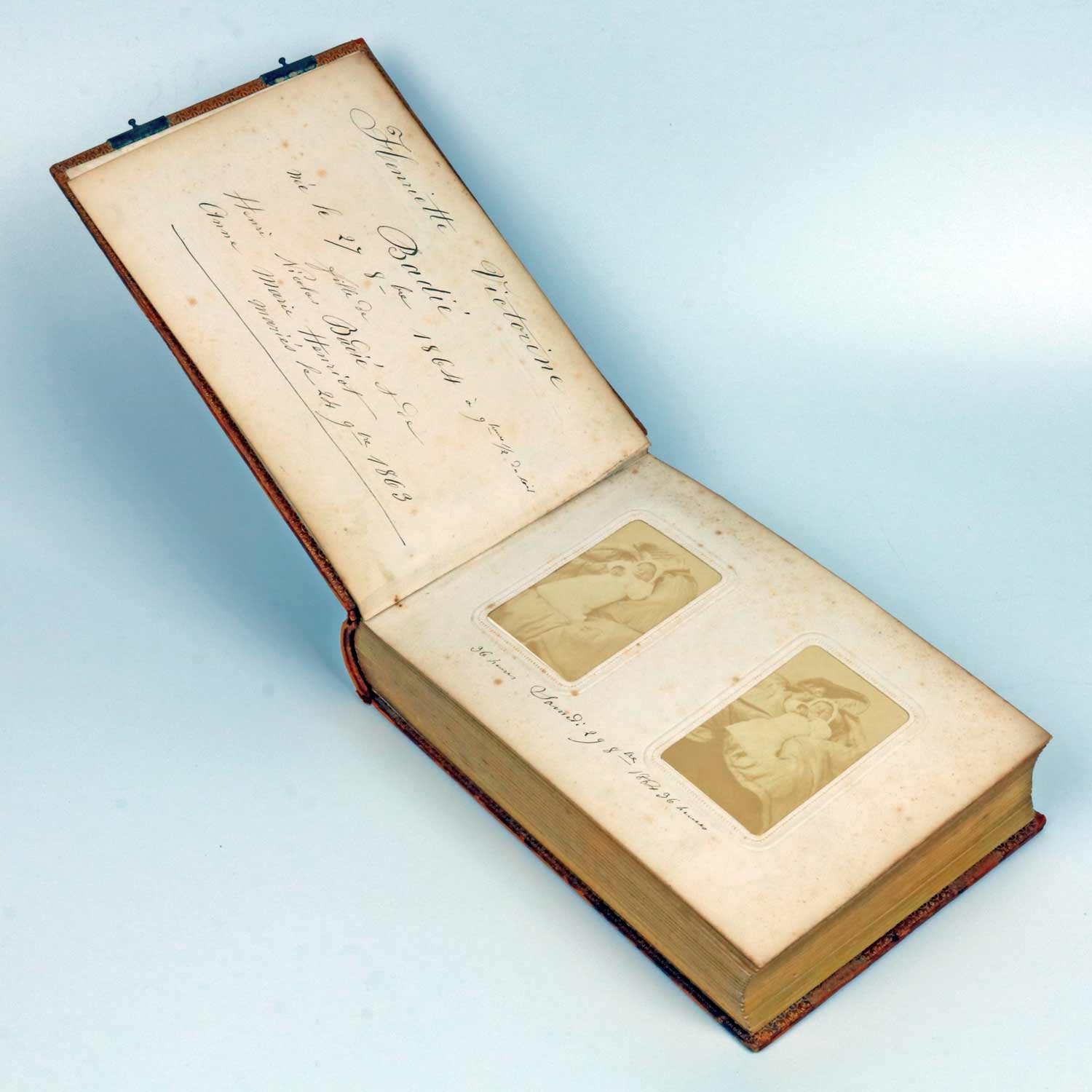

During the summer of 2019, while we were going through stereo cards and photographs at Bruno Tartarin’s professional premises, my assistant Rebecca drew my attention to a photo album she had just leafed through and which had awakened her interest. It recorded the first twenty-two years of a young lady’s life, from the day she was born to her wedding and the birth of her first child. We are used to looking at family albums – either analog or digital – where we can follow the growth of a child from the minute he or she was born to the time when they leave the nest. What made this album unusual was that the photos were all cartes-de-visite which had been taken between 1864 and 1886, in a day and age when it was very uncommon for anyone to have so many records of the passing of time. What had aroused Rebecca’s interest was the number of photos showing the baby girl gradully turning into a young woman and a mother (59 in total). What sparkled mine was the very first page of the bound volume with the name of the sitter and those of her parents. It read thus:

Henriette Victorine Badié

née le 27 octobre 1864 à 9 heures ½ du soir

fille de Henri Nicolas Badié

et de Anne Marie Henriot

mariés le 24 novembre 1863

Now the name Henri Nicolas Badié may not be as famous as Nadar’s, Fenton’s, or Le Gray’s, but I knew it to be that of a photographer who made some stereoscopic daguerreotypes, two of which I had recently bought for Dr. May’s collection at a few months’ interval. I must confess that before the first daguerreotype arrived I didn’t know much about Badié. However, when I examined the back of the plate, which was loosely fitted into its case, and saw his signature pencilled there, I started doing some research on the man, unaware that I would soon be digging much deeper. The first daguerreotype – a gem of fine tinting – came in a foldable case (Figure 1), very similar to the one patented by William Edward Kilburn in 1853 but bearing inside a wet stamp with the initials DS, unmistakably those of French opticians Duboscq and Soleil. Please bear that fact in mind as it will prove of some importance later on. The back also bears the date 13 February 1859, as well as the initials of the model, all pencilled. Was the portrait a last-minute present from the young sitter to someone she held dear on Valentine’s day ? I would like to think so.

The second daguerreotype (Figure 2), although not inscribed on its back, was set in a similar case and looked very much in the same style. It is therefore my opinion that it can also be attributed to Badié with reasonable certainty. Unfortunately I do not know the names of any of the sitters, yet, nor the date when the picture made. However, we may conjecture it was also taken around 1859.

Having those two images in my mind’s eye and with my assistant’s and my interest having been tickled, it is almost needless to say that I bought the album from Bruno, took it back with me to Britain, and forgot about it for at least six months, when I opened it again and launched into some more serious research on Mr. Badié and his family.

Henri Nicolas Badié was born in Sainte-Colombe (Seine et Marne) on 15 July 1828 to François Joseph Victor Badié, 36, a janitor in a roof-tile factory, and Henriette Marie Mignard. He was their third child but the fourth that his father had spawned.1François Joseph Victor’s first wife, Marguerite Rosalie Thévenon, had died at the age of 19, less than two weeks after giving birth to a boy who himself passed away before he was a year old.

Nothing is known of Henri’s first thirty odd years but when he married Anne Marie Henriot, 30, at the town hall of the third arrondissement in Paris, on 21 November 1863, he was already a photographer, operating at 17, Boulevard de Sébastopol. Although Badié’s name only appears in the Paris trade register under “Photographes (Artistes)” in 1860 we know he was already operating in February 1859, and probably even before. There is no telling for sure what he was doing prior to that, nor when or how he became interested in the art of Daguerre. However, since we can see in later advertisements that he introduced himself as a painter and photographer it is reasonable to assume he started his career as an artist and, not being very successful in that field, turned to photography, like quite a few of his fellow-painters before and after him.

The earliest mention of Badié I could find in the press of the time is dated 2 September 1860. One Henri Page,2Henri Page is the pseudonym of William Duckett (1831-1863) a journalist and novelist who was also the collaborator of Eugène de Mirecourt for his biographies. writing in the daily newspaper Les Coulisses, mentions his carte-de-visite portrait by “our friend Badié”. On 11 November 1860, in the same newspaper, Badié’s name appears again, this time in one of those short pieces purporting to be funny and ending in a pun which only makes sense in French. It is about two friends who meet on the Boulevard de Sébastopol. “Where have you been?”, asks the first man. To which the second person answers : “I have just left Henri Badié who has successfully taken my portrait like Disdéri himself would not have managed; what a photographer !” I will spare my English readers the pun which serves as a punch-line but French speakers can read it in the notes.3Le Tintamarre, 11, November 1860.

Un de mes bons amis, qui est en même temps un de nos Calino des mieux réussis, m’aborde hier sur le boulevard de Sébastopol.

– D’où sortez-vous donc, mon bon ? me dit-il.

– Je quitte Henri Badié, il vient de réussir mon portrait comme Disdéri ne l’eût peut-être pas réussi; quel photographe !

– A ça, c’est drôle, me dit Calino, comment se fait-il que j’entende toujours parler de pho-tographe et jamais de vrai-tographe !!!

Another mention of Badié can be found in the satirical journal Le Tintamarre on 31 August 1862. The author, commenting negatively on the illustrations by Gustave Brion (1824-1877) of Victor Hugo’s recently published Les Misérables, exclaims that the only illustration worthy of that beautiful novel is the portrait of the author taken the year before in Brussels and published by Henri Badié.

From 1862 to 1865 Le Tintamarre published several short pieces praising Badié as the best photographer of children in Paris. In the first of these, printed on 2 February 1862, the reviewer attributes Badié’s success in catching children’s truthful and most natural expressions to the quality of his equipment and to the way he manages to capture the attention of his subjects with a sweet, a toy or the stories he brilliantly tells while photographing them. The author of this rather long advertisement, journalist and dramatist Hippolyte Hochard Pervillé (c.1818-1864), writing under the pen name Candélario, concludes in saying that “Mr. Badié has the cutest collection of babies one can see.”

On 5 February 1863, the weekly La Chanson, Revue des Théâtres, Concerts et Cafés-Concerts, inserted in its Variétés column a piece entitled “Prospectus photographiés” (Photographed Flyers) signed by one Jules Maillard. The journalist mentions high end photographic flyers which were commissioned by the directors of the Casino-Français to Henri Badié and include staged scenes and portraits advertising this parisian establishment. More interestingly, he gives a short description of Badié as an artist and not as one of those “oafish” operators who can only obtain very stiff poses from their sitters. Maillard goes on to emphasise Badié’s particular talent in photographing children and writes that he has in his premises “about two hundred portraits of children, portraits of angels, every one as pretty and expressive as the next. He is the mothers’ favourite provider of photographic likenesses.”

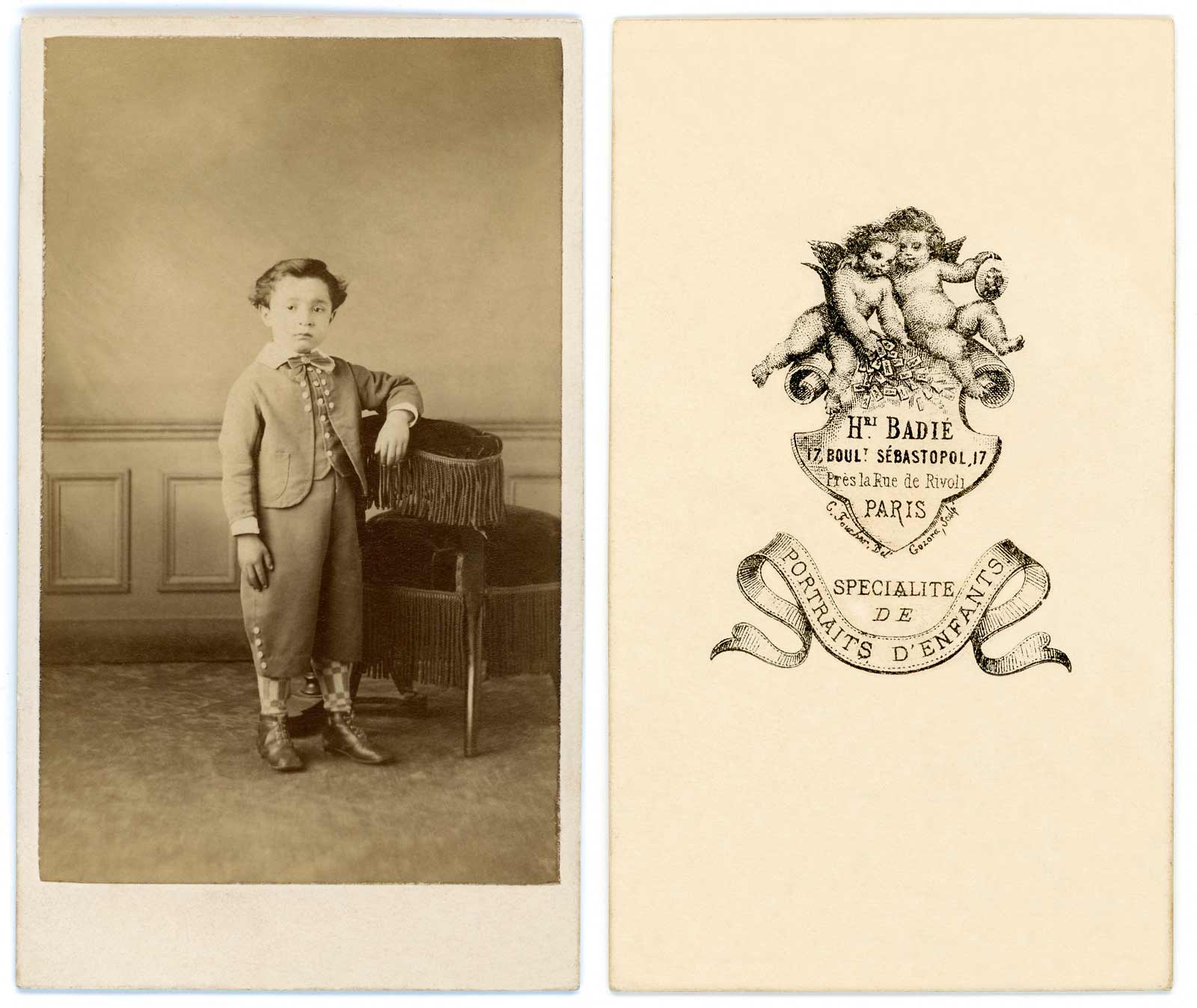

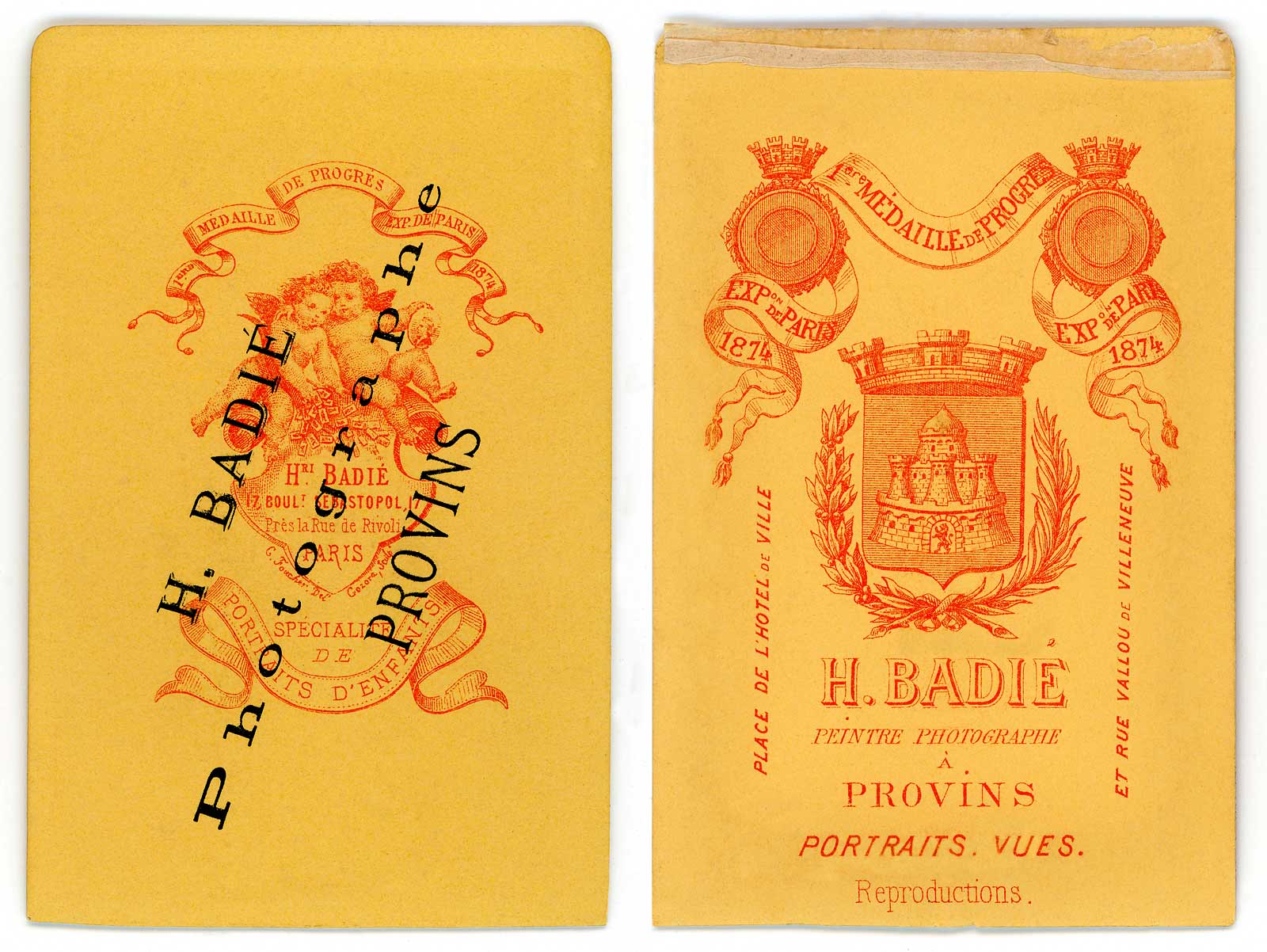

From April 1864 to September 1865, another longish advertisement, signed with the initials A. V. -de C.,4The initials stand for Albert Vuillot de Carteville, a colouful character who had an adventurous youth. He joined the army for the love of a woman, deserted when she lost interest in him and married another man, fled to the Netherlands via Belgium, spent some time with monks there learning German, had a short career as a teacher of philosophy and as a secretary to a Belgian person of renoun, re-enlisted to take part in the Crimean war where he became a hero under a different name and an assumed title, was shipped back to France after being wounded, was eventually recognized as a former deserter when he went to bury his father, was court-marshalled and acquited but was nevertheless sentenced to five years in prison for having “borrowed” a full set of clothes on the day he had deserted. While in prison he wrote to a newspaper to tell his story and express his wish to become he writer, which he eventually did. He ended up a poet, a writer, a lyricist and a journalist who contributed to several newspapers. He was at some point editor of Le Moniteur. was printed verbatim on half a dozen separate occasions in the same newspaper.5This advert was also published, under the same signature, in the Journal-programme des théâtres de Paris during the year 1864. In very laudatory terms, the author, recommends patronising Mr. Badié and reminds the readers of Le Tintamarre that before him a lot of photographers hesitated, or often simply refused, to take children’s portraits because of the difficulties involved in making them stand or sit still long enough. “Mr. Badié,” writes the journalist, “painstakingly overcame those difficulties” which earned him the justified title of “children’s special photographer”. Badié himself chose to advertise his skills in photographing children in a humbler way. On the back of the cartes-de-visite he published after 1870, beneath a nice drawing of two cherubs,6As you can see for yourself, the cherub on the left has next to him a large quantity of CDVs while the other one is holding a portrait which may well be a likeness of the photographer himself. he added the mention “Spécialité de portraits d’enfants” (Specialises in children’s portraits”, which he also used in the entry that was printed next to his name in the Paris trade register for the year 1863.

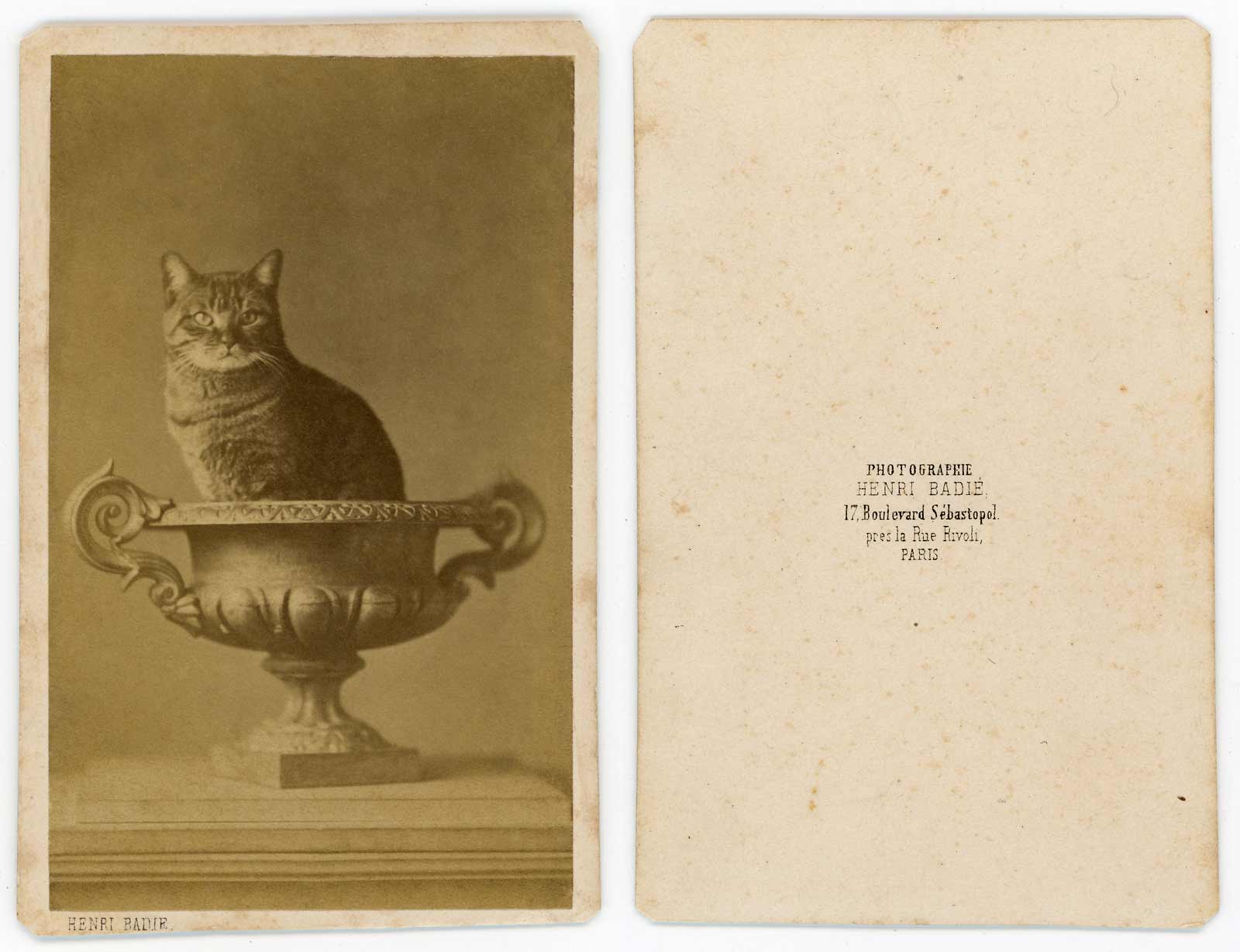

It is, therefore, a proven fact that even before the birth of his daughter Henriette Victorine, Badié was already one of a kind when it came to photograph not only children but also animals if we are to judge by this stunning carte de visite of a cat posing in a vase/urn and looking straight at the camera. Anyone who has tried to photograph one of those very independent-minded creatures will appreciate how difficult it must have been to make it hold still long enough for an exposure that lasted at least several seconds.

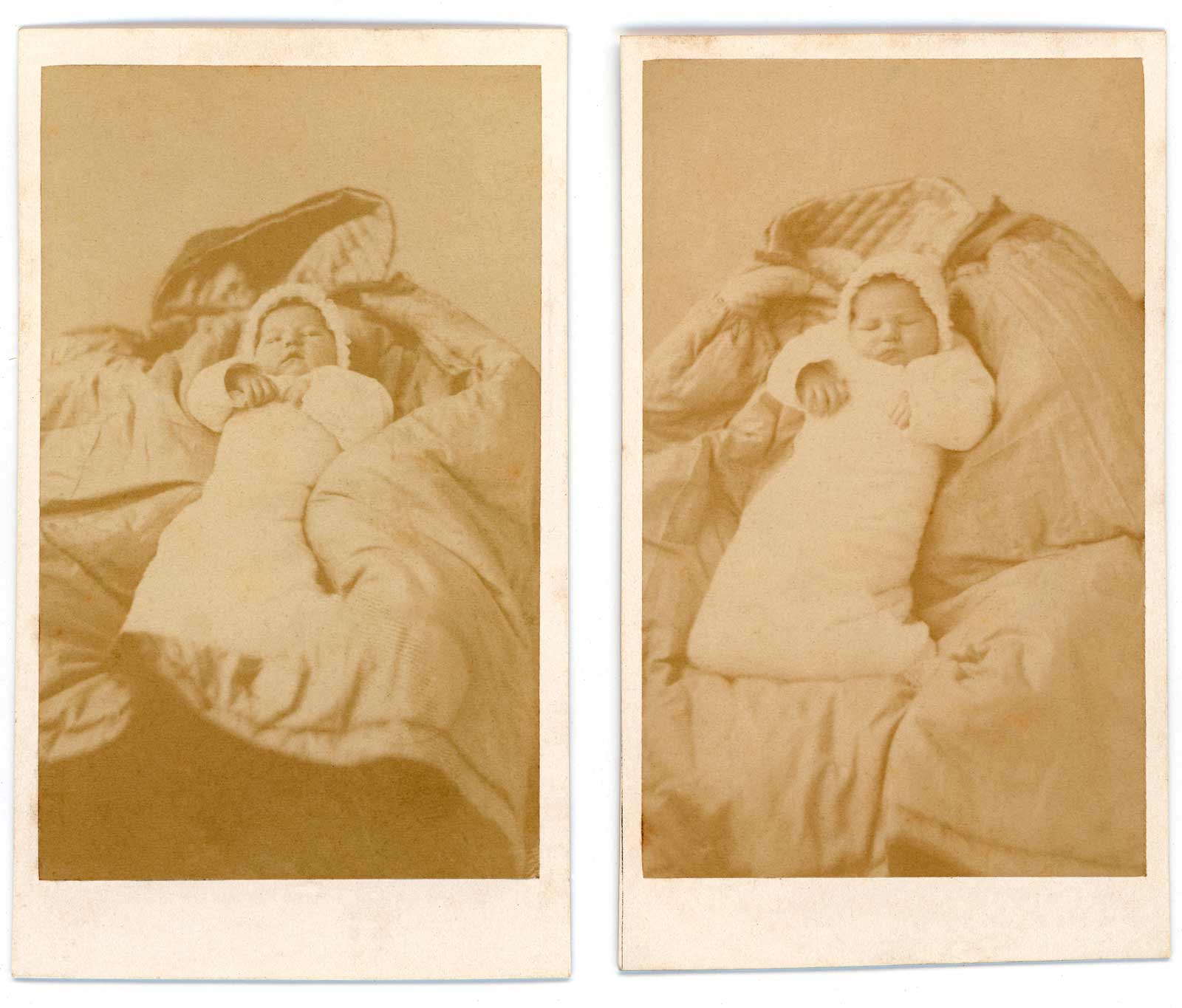

It is time to get back to the carte-de-visite album which sparkled both my and my assistant’s interest. The first two photos which were inserted in it show Henriette Victorine, aged 36 hours and were taken on Saturday 29 October 1864, as we learn from the handwritten caption underneath. In this day and age when babies are photographed seconds after their birth, it may not seem much to make a fuss about but remember this was still the age of the wet collodion process, when photographs were taken on a glass plate which had been covered with a sticky substance, sensitised in a darkroom, put in the camera, exposed and developed at once. Only a photographer whose studio and darkroom were in his living premises could have taken such an image then. Badié probably waited for his daughter to be fast asleep (very young babies tend to sleep a lot), propped her up on a blanket in an armchair and exposed a couple of plates which turned out quite well.

As we turn the pages of the album we see successive pictures of Henriette at six, eight, eleven, fourteen, eighteen and twenty-two months, then at two, three, four, five and six years. The picture showing her at six was taken on 27 October 1870, when Paris had already been under siege for over a month and was to remain so until the end of January 1871. Of the next photo, unfortunately missing from the album, only the caption remains: 27 April 1871 Commune Montfort Lamaury [sic]. It was taken at the time of the uprising known as the Commune (18 March to 25 May 1871) from which we may infer that Badié and his family had managed to leave Paris for a while and were living in the south-western suburbian market town of Montfort l’Amaury. The next two CDVs of Henriette show her age and the date of the shoot handwritten on the basket she is carrying: 7 years 2 days, 29 October 1871.

A couple of puzzling images – four to be precise – feature in the Badié album. Dated respectively 27 April 1873, 27 October 1873, 25 October 1874 and 17 May 1877 they show an eight to twelve year old Henriette wearing a medal which looks very much like the cross worn by the knights and officers of the French Legion of Honour. Being a bit too young to have been awarded what was then a very prestigious decoration, one can only surmise Henriette was wearing treasured family heirlooms. We know her father was not a recipient of the Legion of Honour and nor were her paternal grand-father and great grandfather. The medal must have been awarded to someone on her mother’s side which I have not yet been able to trace. In two of the images she also sports another medal which, not being a specialist, I am sorry to say I have not managed to identify.

Another photograph, captioned “27 October 1878, 14 years”, is also of particular interest, not because it shows Henriette on her fourteenth birthday but because she is posing with her younger sister, Geneviève Pauline, who was born in Paris on 15 July 1872 and was to die in Provins, Seine et Marne, on 11 March 1885, at the age of 12 years, 7 months and 24 days, as stated in her death certificate. It is the only photograph of Pauline in the album.

In March 1881, Henri Badié, who had been operating from 17, Boulevard de Sébastopol, Paris, since 1860, published an advertisement in the Feuille de Provins to announce the inhabitants of that town, in Seine et Marne, that he had just opened a large studio Place de l’Hôtel-de-Ville and was offering portraits in every kind – even after death – by the latest, fastest and most instantaneous processes, in every size and tinted or not. He also put forward his skills in reproducing old daguerreotypes, paintings, pastels, drawings, engravings, etc. This was repeated until October of that year. Badié’s wife and children moved to Provins with him and Henriette continued to be regularly photographed by her father and her portraits to be printed as cartes-de-visite. The photos Badié made after he settled in Provins were still pasted on an old stock of cardboard mounts. He first added a wet stamp bearing his new address over the printed back before having a new back designed.

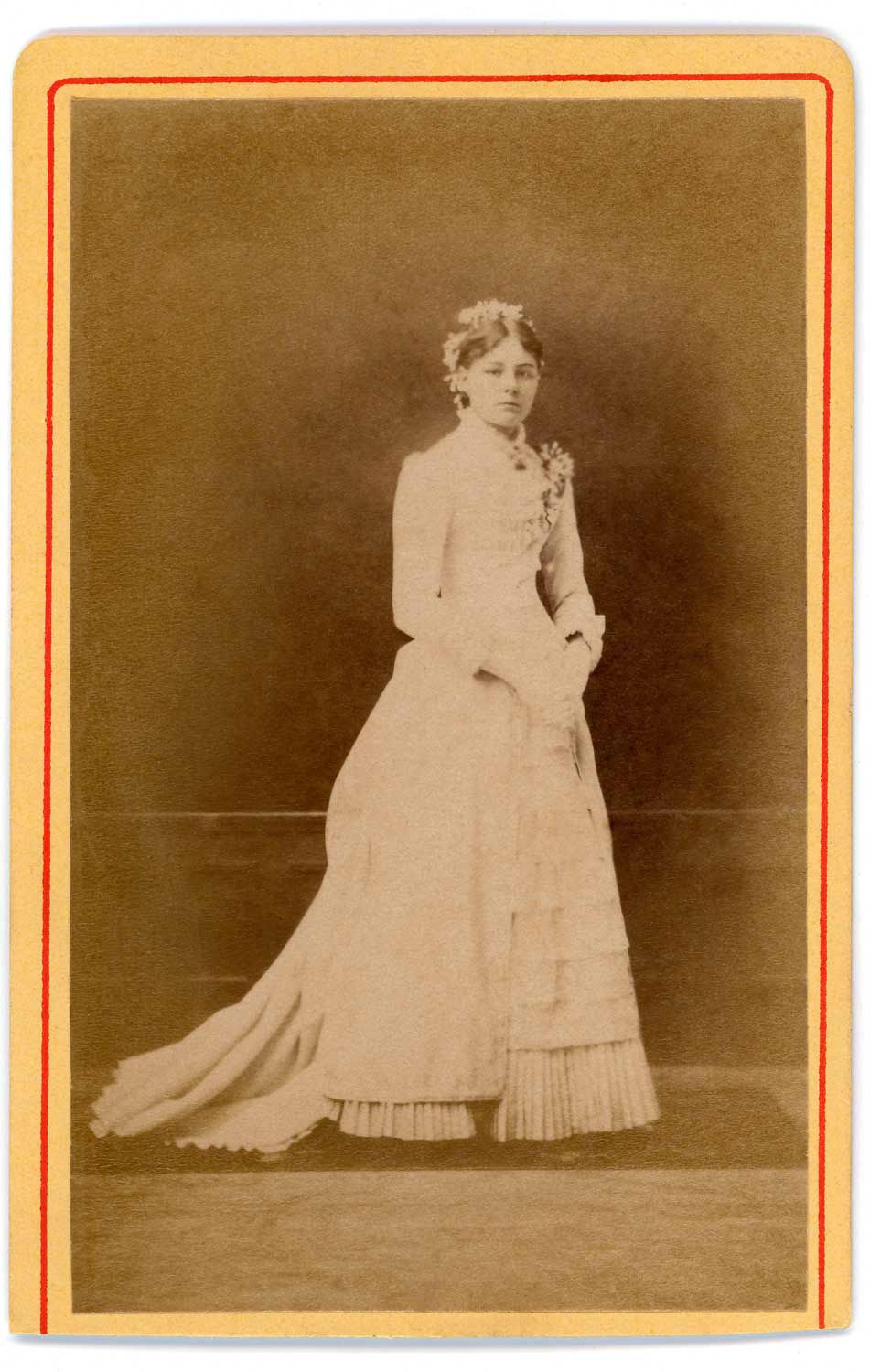

Times passes by as we leaf over the pages of the album until a photograph dated September 1883 shows a 19 year-old Henriette in her wedding dress. The image was captured just before her marriage to a young architect, four years her elder, on 20 September 1883.

Henriette’s husband’s name was Alphonse Jean Nicolas Soleil. He was the son of Henri Jean-Jacques Soleil and Léontine Françoise Orlia and the nephew of none other than Jules Duboscq, the famous optician who had improved, manufactured, and promoted the first Brewster-type stereoscopes before exhibiting them in London in 1851. Duboscq, who was then sixty-six, was not only present at the ceremony but signed the wedding certificate as a witness. We saw at the beginning of this piece that Badié used some of Duboscq & Soleil’s foldable stereoscopes which would indicate that he had had contacts with the family years before Henriette was even born but it is difficult to determine how close they were until they became part of the same family.

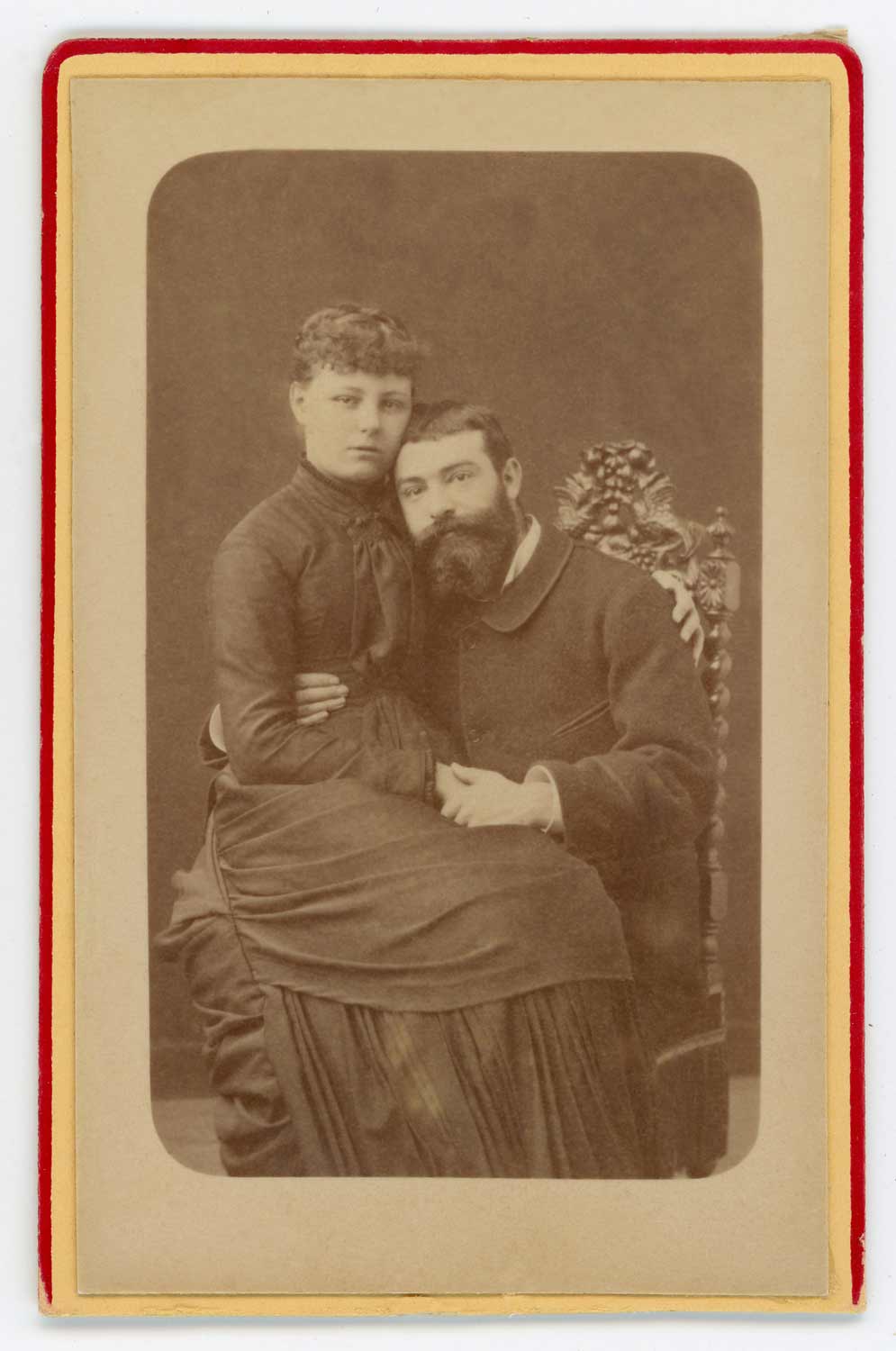

The next photo in the album shows Henriette in April 1884 sitting on her husband’s lap. Although she was still under twenty and he was just over twenty-four, they look more mature than do most twenty-somethings these days who, more often than not, are still students.

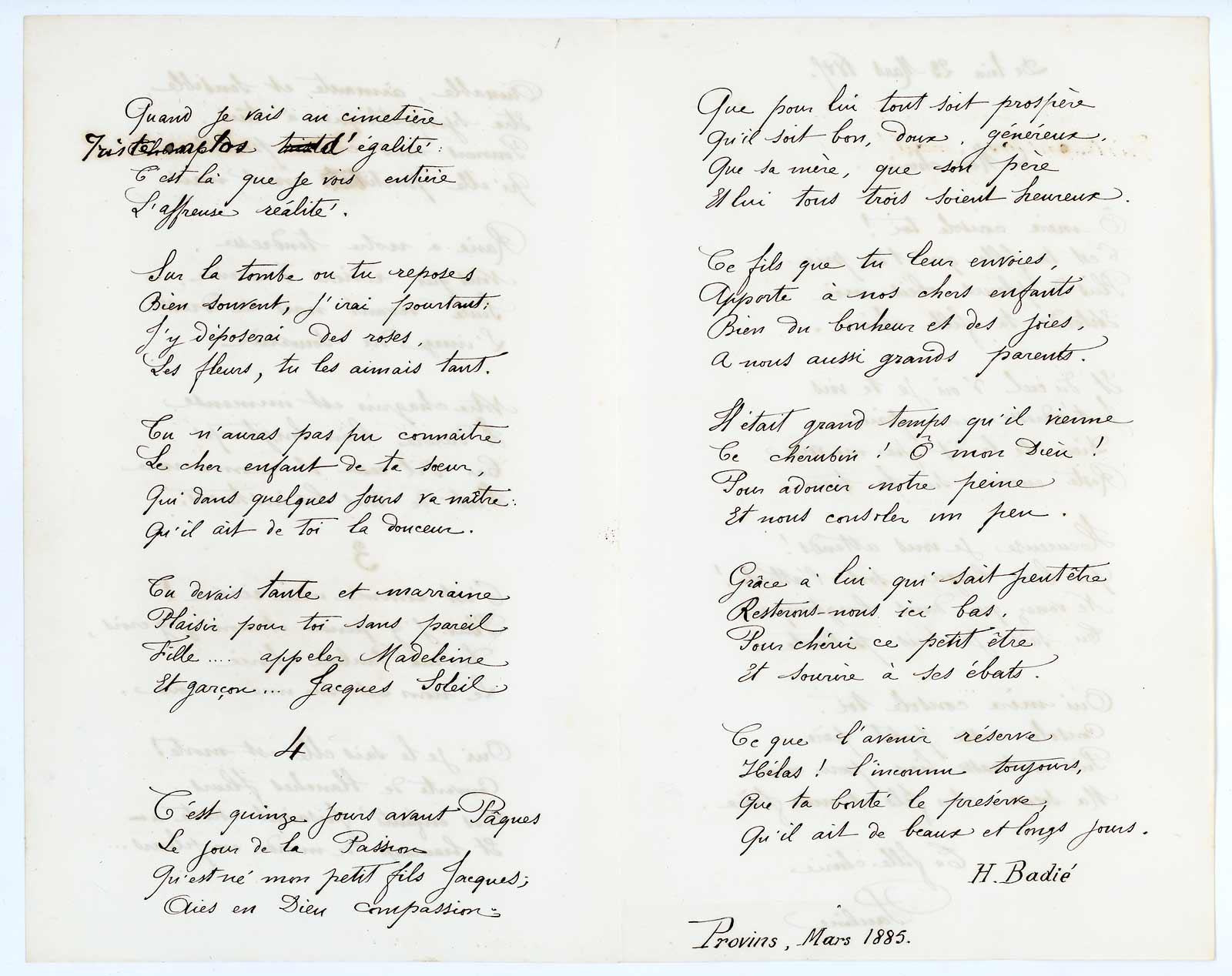

Three more captioned cartes-de-visite complete the album. The first one shows Henriette on her twentieth birthday; in the second image, dated 25 August 1885, she is holding on her lap her first child, Jacques Paul Gaston, born eleven days after the death of the aunt he would never meet, Geneviève Pauline. That there are no earlier photos of Badié’s grandson can probably be explained by the fact the family was mourning the loss of their daughter, sister and sister-in-law. Henri Badié wrote at least two poems about the death of his daughter Pauline. The first one is dated March 1885 and was put to paper shortly after the birth of Henriette’s son, which it mentions as something that partly alleviated their pain. The second one, dated 11 March 1888, was written on the third anniversary of Pauline’s passing and shows how much his grief was still vivid and would always remain so.

The very last captioned photograph in the album shows Henriette on 25 April 1886, two days short of being twenty-one and six months old. There are other cartes de visite inserted in the album – including at least four other pictures of Henriette’s husband – but they are not captioned and we therefore do not know who the sitters are nor whether they could not have been added at a later day to fill up the pages.

Henriette’s husband, died in 1896, just after he got to 36, but Henriette’s father, the photographer who had so patiently recorded the passing of his daughter’s years, lived three months and twenty-nine days past his 75th birthday. He breathed his last in Provins on 13 November 1903. I wish I could have published his self-portrait, which I know exist and a low res copy of which I have seen, but our efforts to contact its current owner have remained vain to this day.

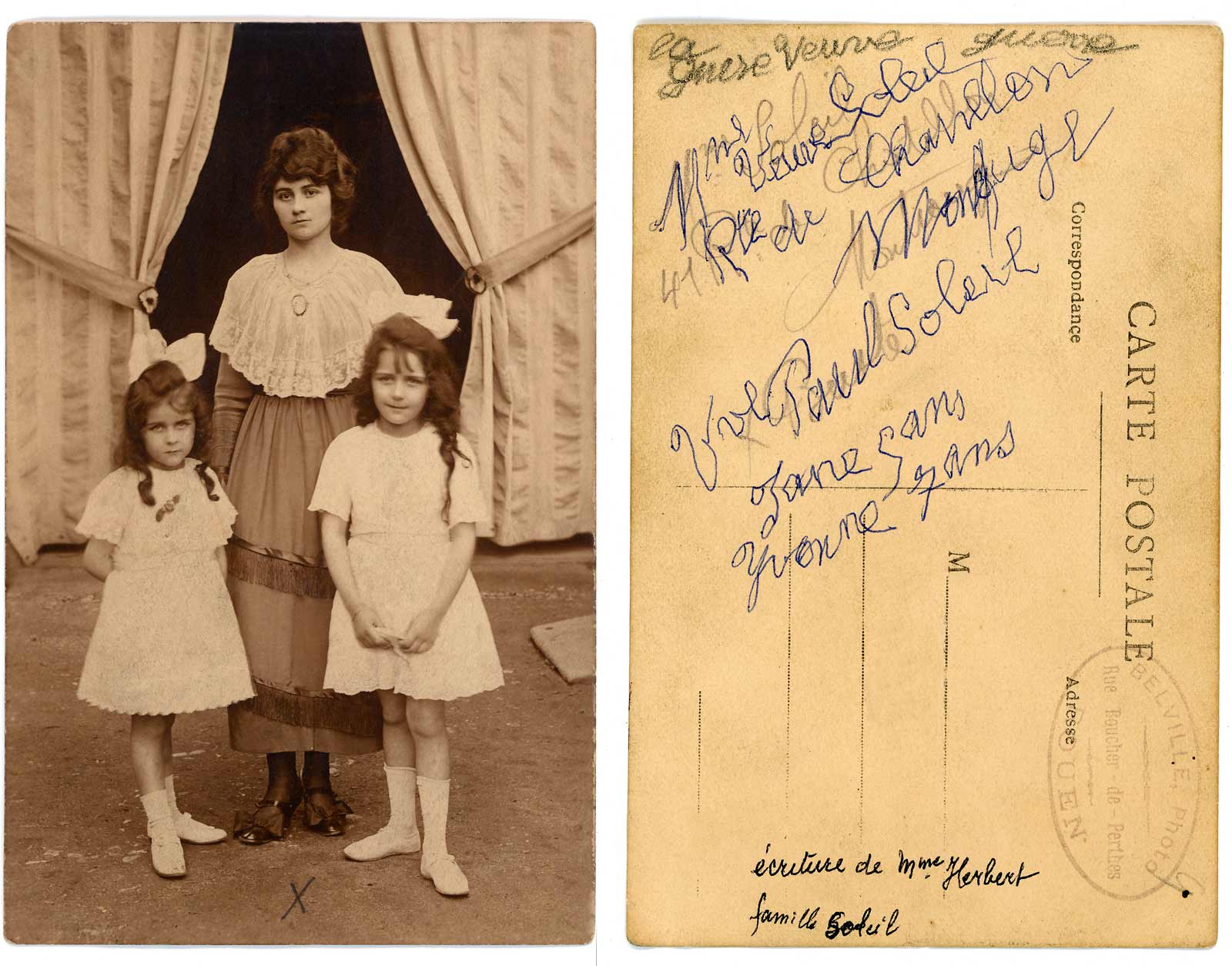

Henriette Badié-Soleil was still alive in June 1918, when her younger son, Paul Frédéric Ferdinand, was killed in action, barely six months before the end of the first World War. He had married Jeanne Véronique Nésa, a hat maker, in Rouen, Normandy, on 17 November 1910. Jeanne is the one who identified the lady in the photo (Figure 05) as Granny Badié, the grandmother of her first husband. Paul and Jeanne had two daughters, Yvonne and Jane, who were respectively six and four when their father died. Here they are on a photographic postcard, with their mother Jeanne Véronique, in 1919. The inscriptions on the back of the card were written when Jeanne was already an old lady and mention she was a war widow as well as the age of her daughters in the picture.

I am sorry to say that I do not know when Henri Badié’s wife passed away nor what happened to her after the death of her husband. Their surviving daughter and subject of the album under study, Henriette, did not live long after her son was killed and died on 2 September 1920. She apparently gave some of the family mementoes to her daughter-in-law Jeanne who, although she remarried in 1939, twenty-one years after her first husband’s death, kept them as precious relics to her dying day.

The album and the rest of the documents, are from two different provenances. I am glad that they are together again, by pure chance, and that they can help add a small but hopefully interesting piece to the history of photography, of the carte-de-visite and of the stereoscope.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank Bruno Tartarin and David Tournedouet who, between them, provided me with the documents I needed to write this article.