All images are from Library of Congres.

All are by the Loman Brothers Studio, except where noted.

In the wake of Nome’s gold strike, the winds of opportunity blew a family into this boomtown that would become its wealthiest: shrewd hawkers of reindeer meat, Santa, and his sleigh. In 1903, Carl Lomen and his father, Judge Gudbrand J. Lomen of St. Paul, Minnesota, moved to the Seward Peninsula’s Sin City after a working vacation there. Carl’s mother, four brothers, and one sister soon followed. Lomen senior had hoped to profit from settling claim-jumping disputes but ended up forging a multi-tentacled corporation instead.

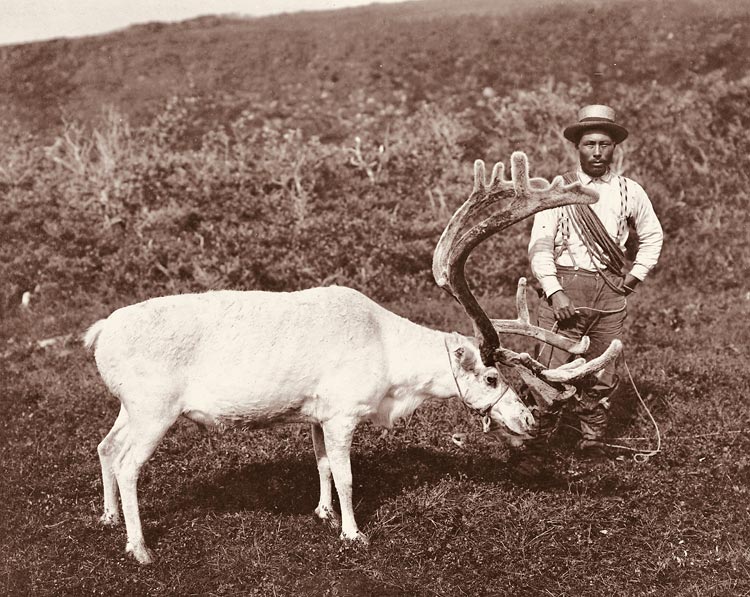

Carl’s initial sighting of the creatures that made the family’s fortune paints a rather citified picture of him. On the tundra in the summer of 1900, a herd stopped him dead in his tracks. Ignorant of the habits of reindeer, he feared they might attack.

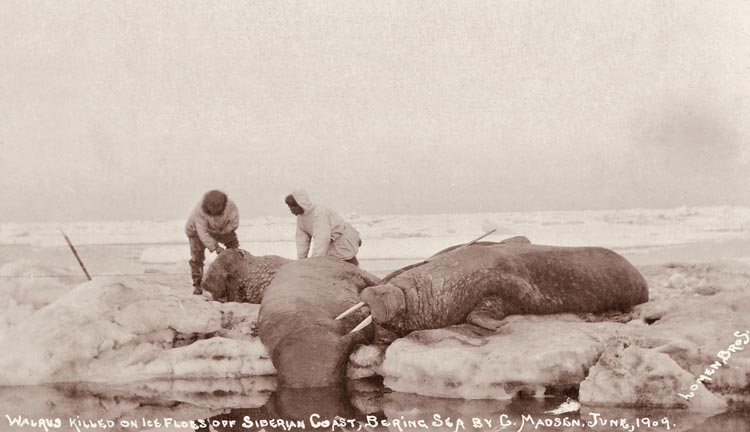

In 1908, the brothers bought a photo studio, as well as equipment and glass plate negatives from other photographers,the latter of which they sold under their name – an accepted custom in those days. Though Harry managed the studio, all of the brothers took photographs. They quickly mastered the art, learning to keep cameras and fingers functioning at sub-zero temperatures. Chasing elusive camera angles, Alfred, the most prolific of the siblings, who joined Nome’s basketball team, once rowed to a 10 by 6 ice floe and set up his tripod. Amazed passengers aboard S.S. Victoria took pictures of the picture-maker. He also managed The Nome Daily Gold Digger, one of several local newspapers.The Lomens’ studio on Nome’s muddy artery, Front Street, offered “Kodak Finishing of the Better Kind.” They sold photos as postcards and to newspapers and scientific publications, cashing in on local color and the territory’s new popularity. In 1914 the family launched a successful reindeer business with animals from an ageing Saami (or “Laplander,” a term now considered offensive). It built its first refrigeration plant on the frozen banks of Elephant Point, where the remains of a mammoth, “flesh and hair still intact” had been discovered. By 1916, the Lomens were shipping meat to the Lower 48.

A savvy publicist, Carl,employing Inupiaq seamstresses, assisted in outfitting the Norwegian Roald Amundsen, with reindeer-skin mukluks and sleeping bags from their herding and meatpacking operation. The studio produced a signed portrait of the explorer that served as a model for the bronze bust that now greets tourists who saunter down Front Street.Dismaying the cattle industry, Carl used radio and print ads to convince the public stateside that reindeer were a readily available, leaner, cheaper beef alternative: “America’s New Health Meat.” He approached railroads and large New York hotels, asking them to put reindeer venison on their menus.

In 1923, Santa’s antlered bunch endured “a very windy snowy dark day” harnessed to a red sleigh while he handed out presents to every wide-eyed child at Holt’s hardware store on behalf of the Lomens, on Christmas Eve. Co-opting Saami and Siberian cultures, these midwestern transplants pioneered minting a holy day into a capitalist opportunity.

A 1925 silent short film shows Santa in his North Pole workshop visiting “Eskimo neighbors” and taming and harnessing his sled deer. It’s “a fantasy actually filmed in Northern Alaska” that toured the U.S. around Christmastime. In the denouement, the shockingly skinny protagonist wiggled down a Nome chimney. Lomen reindeer played the parts of Donner, Blitzen, and Co.

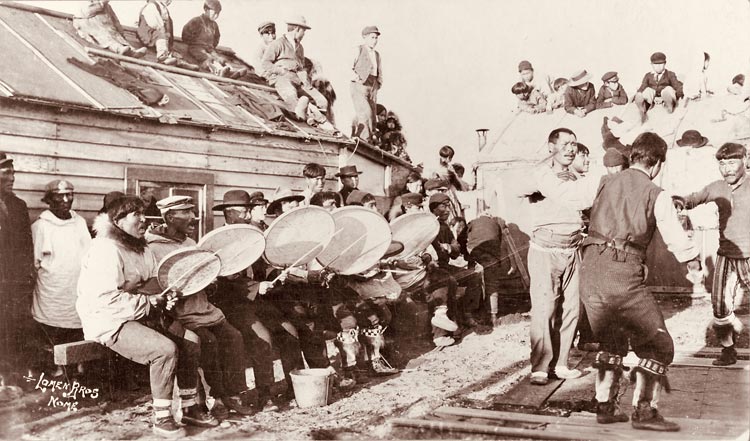

Partnering with Macy’s department stores, the Lomens the following year took their pageantry stateside – eventually enchanting Brooklyn, Boston, Chicago, St. Paul, Portland, Seattle, and San Francisco. Saami and Inupiaq handlers stood in for the elves. The Lomens also faked children’s letters to Santa, which U.S. newspapers published. Police had to control ecstatic crowds at those parades, and the rest is Christmas history…

Carl Lomen, who boasted of the family’s “many pleasant relationships with the native people,” pledged that he and his brothers represented no threat to Nome’s herders, as the family would focus on those national markets. By then, however, most miners had left the region, leaving no significant local buyers. Lacking the funds to build slaughterhouses or underground cold storages – natural freezers that took advantage of permafrost – Inupiaq herders couldn’t compete on the national stage, in part because they had no stateside connections. Conflict over prime rangeland mounted as the Lomens came to control the best grazing grounds, charging native herders a use fee and collecting a herding fee for each Inupiaq reindeer that got mixed up with his animals.

In his 1954 memoir Fifty Years in Alaska, Carl Lomen gave patronizing dues to Native resilience and good humor. “Civilized men,” he wrote, “would become despondent living under like conditions, but the Eskimo meets them lightheartedly. He exhibits no concern for the morrow.” Pages later, the entrepreneurial meat-packer contradicted himself with a quote from Inupiaq herder William Allokeok of Shishmaref: “If you wish a good living from your deer, you should think and plan how to care for them. If you don’t, your herd will decrease.”

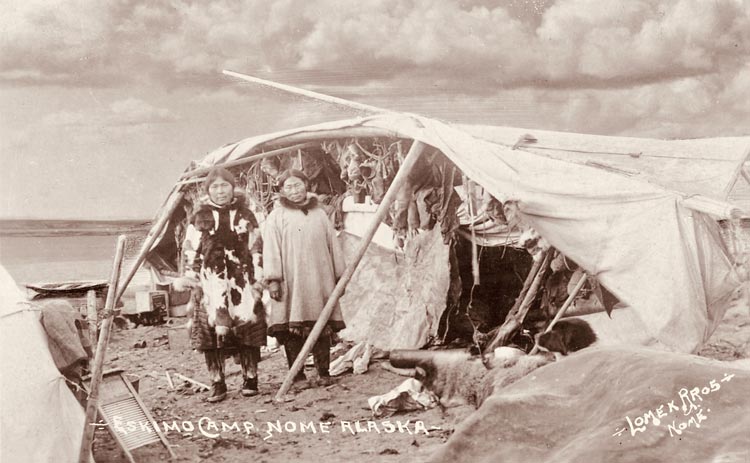

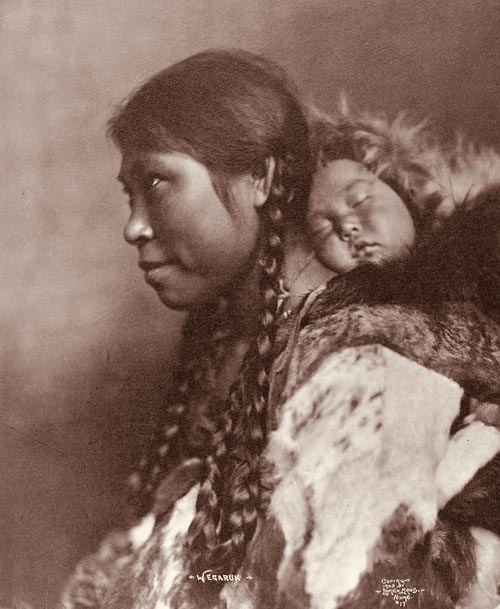

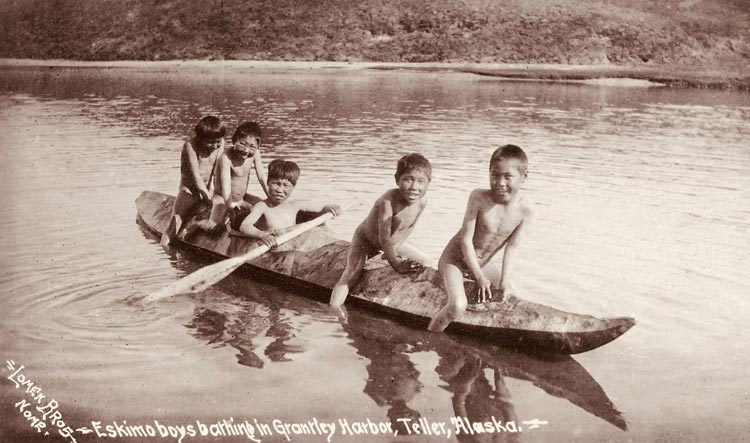

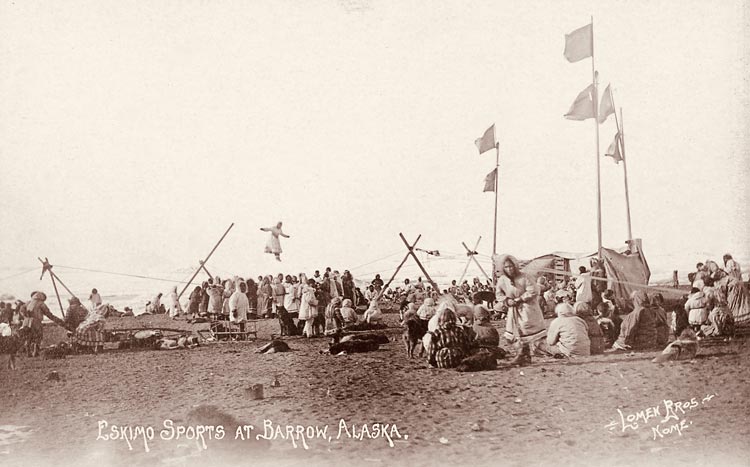

Lomen photos helped to sell meat along with the fiction that herding benefitted all Alaskans equally. They show Native youths straddling reindeer, and herds streaming across tundra, a tide of furry backs. There are dancers with wolf-head hoods straight from a creation myth. There are broad faces haloed by fur ruffs, and beauties with raven hair cascading cape-like, hiding their upper torso.

Lomen images featured bare-chested Siberian Yupik girls and one a mother nursing two infants. Both kinds, the indiscrete and the idealized, fed an exoticism stoked by polar explorers, by East Coast “natural history” exhibits – such as the Greenlandic boy Minik and his Inuit relatives – and by expositions such as the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair. The Nome photographer Beverly Bennett Dobbs for his shots of Alaska Natives won a gold medal at that event. Discovering a yen for filmmaking, he sold his photo negatives, store, and supplies to the Lomens, who kept issuing some of Dobbs’ work but with their own white, watermark signature in the corner.

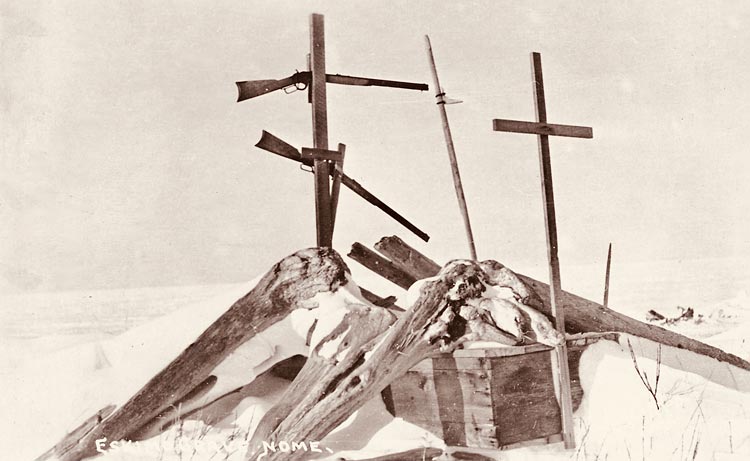

While these crisp photos preserve ethnographic treasure, many are studio portraits of Inupiat in splendid traditional garb, staged in the style of those by Lomen’s contemporary, the one-time Nome visitor Edward S. Curtis. Curtis had arrived in Nome in the summer of 1927, for a Bering Strait tour during which he gathered material for the final volume of his magnum opus, The North American Indian. In a portrait he sat for, for one of the Lomen lensmen, he looks professorial – round steel-rim glasses below a white wispy tuft sticking up from his balding dome; still trim, still sporting Buffalo Bill facial hair, plus a vest and tie; tendrils ghosting up from a cigarette leisurely held, his other hand cradling that elbow – an impression negated by a suit jacket boldly striped.

The September 1934 conflagration, razing most of the Nome’s business district, destroyed the studio and 25,000-30,000 negatives and finished the enterprise. Luckily, about 3,000 of these glimpses into a glorified past survived. Sepia-toned images of Native Americans captured by Curtis and the Lomens, in the words of one curator, “continue to speak to countless people worldwide who encounter them on postcards, book jackets, posters, [or in] galleries, and museums.” The sources are mute about what compensation, if any, the subjects received.

Michael Engelhard lived briefly on Lomen Avenue, a block to the west of the former Discovery Saloon, Nome’s oldest surviving place of business, which housed the Lomens when they first came into town. The award-winning author of the memoir Arctic Traverse and of the essay collection No Place Like Nome, Engelhard has a background in cultural anthropology. His books are available on Amazon.