Interview with Nicholas Burnett

At the beginning of the 1990s, Nicholas Burnett, collector and photography conservator, well known in the UK and abroad for his Cambridge-based studio, Museum Conservation Services Ltd, attended a monthly book fair at Fisher Hall in Cambridge as there would sometimes be photographs there.

– I came across a dealer in ephemera who had a box of magic lantern slides. Among them, I found an early colour photograph, a very good one. I asked him if he had more and he said, “Yes, but you will have to come by my house because this is the last fair I’m doing as I’m retiring.” I took his details. His name was Lewis F. Leopold and he lived in March, Cambridgeshire. I often take people’s details without following up but a few months later I called him and arranged a visit. He had a huge garden, with four big sheds just filled with material. He climbed up some steps and handed down boxes of magic lantern slides, wonderful early colour images, made with the subtractive process, which is much rarer than those made with the additive process.

Lewis F Leopold told Burnett that he had been close to throwing them away.

– He said that they were so heavy to take from fair to fair but he had decided to hang on to them, figuring that somebody would want them one day. I asked him about the prices and he said, “They’re 20 pence each but if you buy a group, I’ll do you a deal.” I ended up buying 300 for 50 pounds. On the way back, my wife Barbara said, “Why didn’t you just buy them all?” The next day I called him and asked “How much for the rest?” and he said, “Another 50 pounds.” and bless him, he got in his car and delivered them to me.

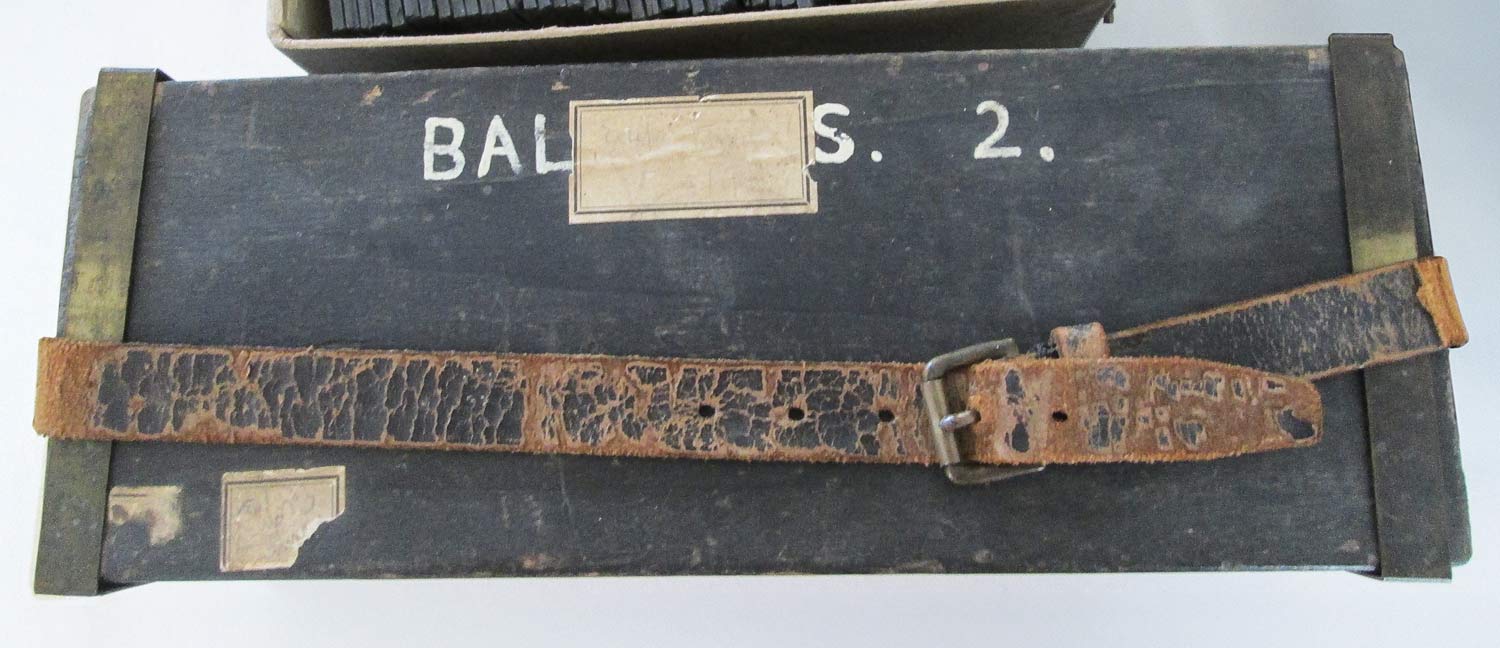

The slides had white writing on the binding strips.

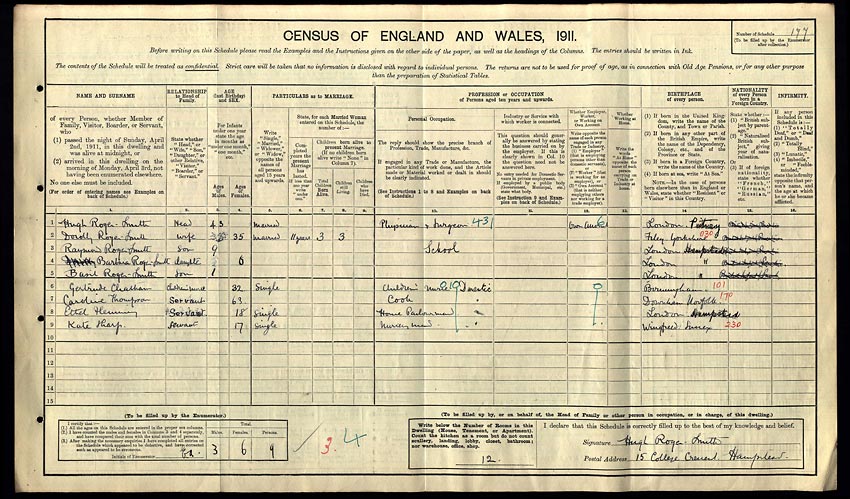

– The writing identified the locations but there were no indications as to the identity of the photographer. Still, on one slide I spotted some writing that might lead to an identification, “Dot Ethel” and “Belsize Crescent”. I surmised that the photographer had lived there. Fortunately, there is only one Belsize Crescent in the whole UK and it’s in Hampstead. I looked online and came across Hampstead Photographic Society which had been founded in 1937, and before that there was the Hampstead Scientific Society which had founded its own photographic section in 1901. I suspected that the magic lantern slides I had bought had been for public lectures so I started going through the yearbooks of the societies to find possible candidates. I also looked at census records, searching for Dorothy plus Belsize Crescent and came up with Dorothy Margaret Simpkin who lived in the same house as John Henry Peered, and Edward and Winifred Evelyn Howard. I figured, “Maybe the man of the house had been a keen amateur photographer, John Henry Peered Simpkin”.

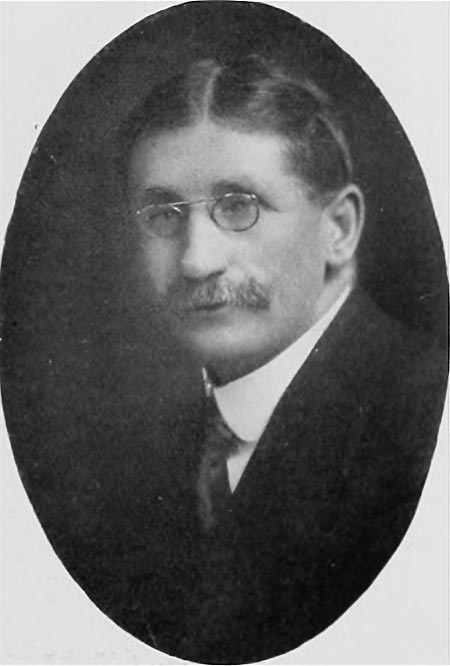

I researched him, looked him up in a post office street directory, found out when he had died and I contacted his family, but they didn’t recall anyone in the family having been a keen photographer so I went back to the records of Hampstead Scientific Society, looking for someone who had given lectures on colour photography or used colour photographs in lectures. I came up with two names. The first was a woman, Mrs Edward Shenton. The other was Dr Hugh Roubiliac Roger-Smith. She lived at number 7 Heath Mansions Grove, he at number 1 College Terrace so neither resided in Belsize Crescent. Going through the yearbooks, I discovered that Roger-Smith had given a lecture entitled 10 Days in Holland on 18 March 1910 and in 1909 he been awarded a bronze medal for his view of Arosa. He received special certificates for his Autochrome work. As the group of slides I’d bought included views of Holland, I suspected that he was the photographer I had been looking for.

Burnett continued his research.

– I found out that he had jointly founded the Alpine Garden Society in 1927, that he had written a report on a 1929 plant hunting expedition in the Balkans, subsequently published as a book in 1950. And when I looked him up in the census records, I found that his wife was called Dorothy, “Dot”, and that they had had a parlour maid named Ethel. That solved the Dot Ethel mystery. I looked up the addresses they had lived at, none of them were in Belsize Crescent. I assume the photograph that bore the relevant inscription was made during a visit to somebody in Belsize Crescent. As for the parlour maid, presumably they must have been very informal with her!

Burnett caught COVID very early on in the pandemic.

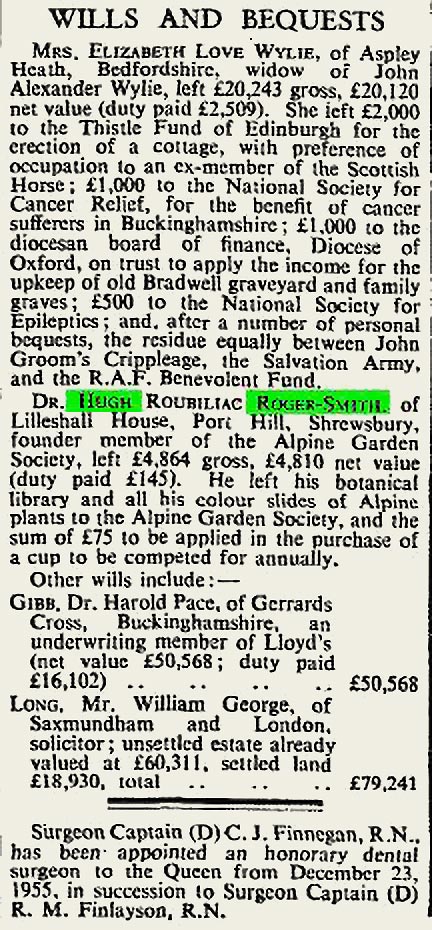

– During my recovery, I decided to search for Dr Hugh Roubiliac Roger-Smith online and came across a website, www.lost-balkans.com, devoted to a large group of lantern slides that a chap had bought at a car boot sale. The chap’s name was Robert John Speer, I contacted him and he very kindly sent me an image of a sample of the hand-writing from one of his slides and it matched mine perfectly. Dr Hugh Roubiliac Roger-Smith had left all his Autochrome slides of alpine plants to the Alpine Garden Society in his will. Bob Speer had contacted them but didn’t really get anywhere. I assume that the slides were disposed of in the 60s or 70s, perhaps because they were deemed to have no further scientific value.

Anyway, it was a slam dunk case, Hugh Roubilliac Roger-Smith was the photographer. Since then, various people have been very helpful with supplying additional information on him and his photography, including Janine Freeston and members from The Photographic Collector’s Club of Great Britain. All adding bits to his biography. He had started out as a mountaineer but following the deterioration of his joints, he turned to hunting plants in the Balkans for Kew Gardens. He died in 1955. He and Dorothy had a daughter who became a nun so that branch of the family has died out. Still, he left behind some really wonderful images, not just of the Balkans, but of Holland, Switzerland, the UK, still lifes that are reminiscent of Dutch genre painting and some exquisite images of hay stacks that remind me of Monet.

Burnett adds a final note on the composition of the group of images.

– The earliest colour images in the group were all made using the Sanger Shepherd colour process. This was a time-consuming process requiring three separation negatives to produce three complimentarily coloured positives which were then superimposed to create the final image. It did give lovely, bright images, much more so than the Autochrome process. The Autochrome had two great advantages though; it needed only a single exposure and was both quick and simple to process. Dr Hugh Roubiliac Roger-Smith seems to have switched to using Autochrome plates soon after their release. He also tried out other screen processes as they came onto the market.

In all, the group comprised:

314 Autochromes,

281 Sanger Shepherd colour process,

5 Thames colour plates,

4 Dufay Dioptichromes,

3 Ives dye imbibition transparencies,

78 monochrome images,

and a slide with samples of screen types: “Autochrome (1907), Dufay (1909), Thames (1908) and Omnicolore (1907)”