Giovanni Teeuwisse is a photography specialist at the auction house Bassenge. In this interview he talks about growing with art, falling in love with photography, his education, joining Bassenge, the state of the photography market and his private photography collection.

Can you tell me a little about you background?

– I grew up in Berlin, the son of a Dutch art dealer and a German artist. While my name might suggest that I am Italian, it’s actually a nod to my parents’ love for Italy, where we spent a lot of time when I was growing up. I have had an active interest in photography for nearly half of my life, so if you have attended any major photography event in the past 15 years, there’s a pretty high chance we might have crossed paths.

You were pretty much born into the art world?

– I guess you could say that, although it probably sounds a lot more glamorous than it really was. My grandfather, Arie Teeuwisse, was a well-known sculptor in the Netherlands, so art has always been a significant part of my life – whether it was drawing in his studio, visiting artists’ workshops, or interning at the Museum Beelden Aan Zee, where many of his sculptures are held. My father, who specialises in Old Master prints and drawings, also exposed me to a lot of great art from an early age on. Through him, I regularly attended fairs such as TEFAF Maastricht and the Salon du Dessin in Paris, which made for an interesting glimpse behind the scenes and further deepened my connection to the art world.

When did your interest in photography begin? And how did it evolve?

– My fascination with photography began when I was 14 after seeing an exhibition by Henri Cartier-Bresson in Amsterdam. I remember standing in front of his photographs, feeling as though I was peering into these fleeting moments that would have otherwise been lost to time. That was the first time I truly grasped the power of photography – the ability to distill life into a single, meaningful frame. That experience introduced me to the concept of the decisive moment and sparked a lifelong fascination with photography.

Are there areas, styles, themes, etc., that you are particularly interested in?

– There really are too many to mention, but I’ve grown particularly fond of nineteenth-century portraits and topographic views over the years. There’s just something utterly captivating about seeing the world through the eyes of someone who might have had a conversation with figures like Jules Verne or Charles Baudelaire or traveled through feudal Japan or the Ottoman Empire. That said, my interests are always evolving, and I’m constantly discovering new areas within the medium.

Where and what did you study?

– I studied Art History at Humboldt University in Berlin, where photography and new media were already key areas of focus at the time. After that, I completed a graduate program at the George Eastman Museum, which was a transformative experience because it allowed me to work with a lot of material I had only read about before – studying Gustave Le Gray’s work up close, for example, or cataloging parts of the museum’s holdings of prints by Eugène Atget. Later, I completed a master’s degree in Contemporary Art at Sotheby’s Institute of Art in London, where I worked closely with Dr. Juliet Hacking, who had a major influence on my understanding of the fine art photography market and its role in the global art world.

When did you join Bassenge?

– I interned at Bassenge for a year after finishing my studies at Humboldt University and was offered a full-time position a couple of years later when a former colleague retired. Joining Bassenge had been a longtime goal of mine – I had followed their auctions for many years and even bought my very first artwork there: a stunning portrait by Nan Goldin that reminded me of Modigliani’s work in a way, while still being unmistakably Goldin. Her ability to create these raw, evocative portraits of her entourage had always fascinated me.

You work alongside Jennifer Augustyniak, one of the most highly regarded auction specialists in the world. What are the main things have you learnt from her?

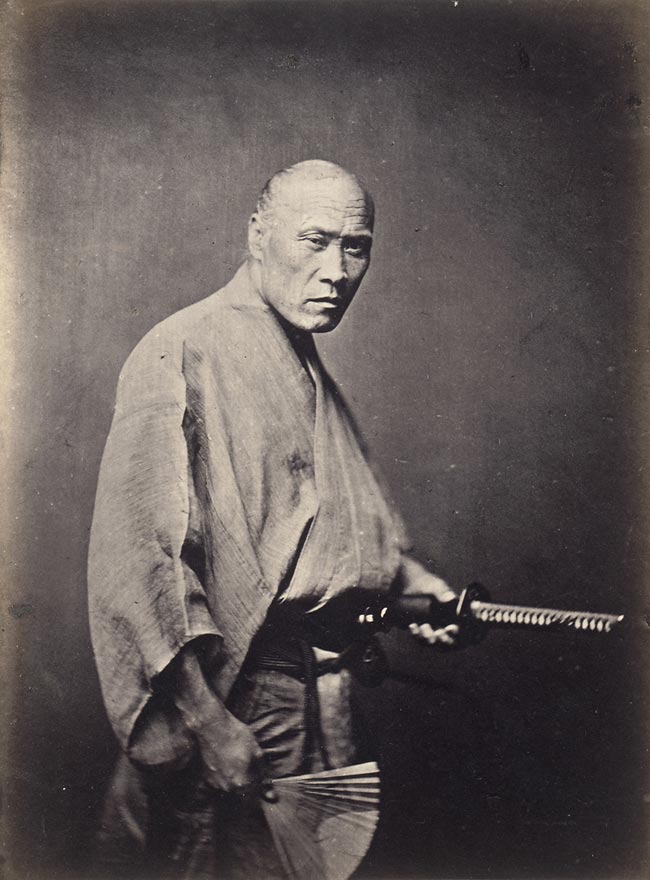

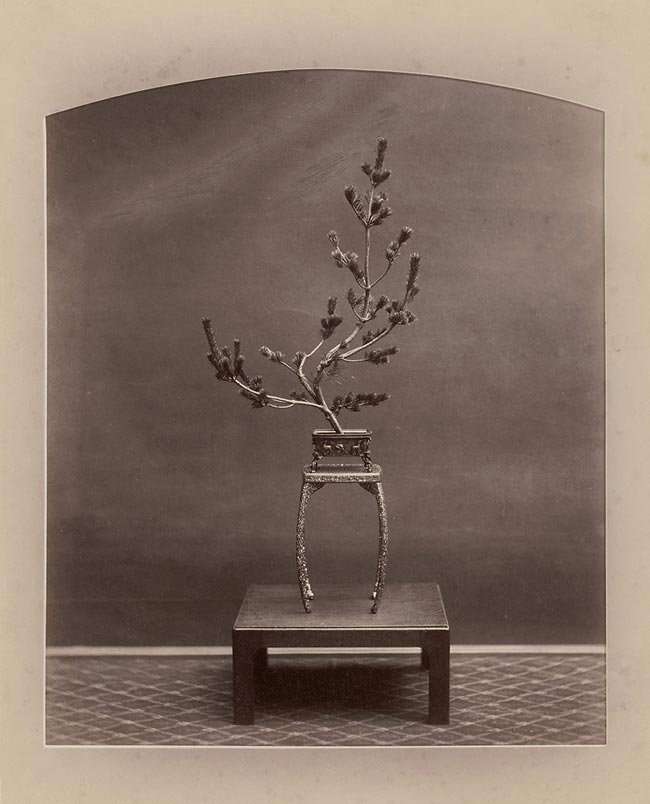

– The most valuable lesson Jennifer has taught me is that every photograph deserves your attention, no matter how obscure it might seem at first. She proved this to me early on when I was given a portfolio of albumen prints featuring Japanese bronze ware for Ikebana arrangements. We didn’t know who the photographer was at first, but after some research – and the help of a friend who translated the stamps on the back – we discovered it was the work of Nakajima Matsuchi, one of the most decorated Japanese photographers of the late 19th century. The portfolio ended up selling for over six times its estimate. That experience was a powerful lesson in the value of diligence and thorough research.

When I speak to people in the auction world, they say that acquiring market knowledge about contemporary photography is easy compared to vintage photography. Has it been a steep learning curve for you?

– I think that perspective oversimplifies things. While contemporary photography often comes with clearer provenance, making research more straightforward, vintage photography has many factors that determine its value. That said, contemporary photography presents its own challenges – the wide range of new printing techniques and supports requires specialized knowledge, and staying informed about emerging trends is crucial. What makes photography so exciting is its constant evolution – new techniques, perspectives, and innovations are always emerging so there’s always something new to learn. I’m especially interested in how contemporary artists are reinterpreting historical processes, blending digital with analog, and pushing the boundaries of what a photograph can be.

What are your thoughts on the current state of the market?

– The photography market is going through a major shift. Interest in certain areas, such as 20th-century modernist photography, has softened, while previously overlooked or rediscovered areas are gaining momentum. Some once highly sought-after works no longer hold the same appeal while emerging areas – such as work by queer and female photographers or practitioners from the Global South – are seeing increased recognition. That said, photography still commands strong interest, as seen in the continued success of events like Paris Photo and AIPAD New York. Collectors are becoming more discerning, which is ultimately a good thing. I genuinely believe that those who take the time to research and source exceptional works will always find a market for them.

Recruiting new collectors to the classic photography market is an ongoing challenge. Do you have any ideas or strategies for the future?

– Education is key. When I worked as an art advisor in Paris, I quickly learned that the best way to engage new collectors is by helping them understand what they’re looking at. At Bassenge, we do this through our auction catalogues, which provide detailed insights into nearly all of the lots offered, and through platforms like Instagram, where we regularly share highlights from our auctions. One of the biggest hurdles for new collectors is the intimidation factor – understanding what makes a print valuable, how condition and provenance affect pricing, or simply how to start collecting in the first place. Making the market accessible and approachable is essential for bringing in the next generation of collectors.

Do you collect yourself?

– Yes, I have a small but eclectic collection. It started with that portrait by Nan Goldin and has since expanded to include works by Harry Callahan, Richard Misrach, Peter Hujar, Francesca Woodman, Thomas Ruff, and Nobuyoshi Araki. I also have a small collection of nineteenth-century photographs, including works by Édouard Baldus, Auguste Belloc, Félix Nadar, Felice Beato, and Kusakabe Kimbei. Each piece holds a special meaning to me – some for their historical significance, others because they resonate with my personal aesthetic. Collecting has also greatly influenced my work as a specialist: when you collect, you train your eyes, refine your taste, and develop a deeper intuition for what makes a photograph compelling.