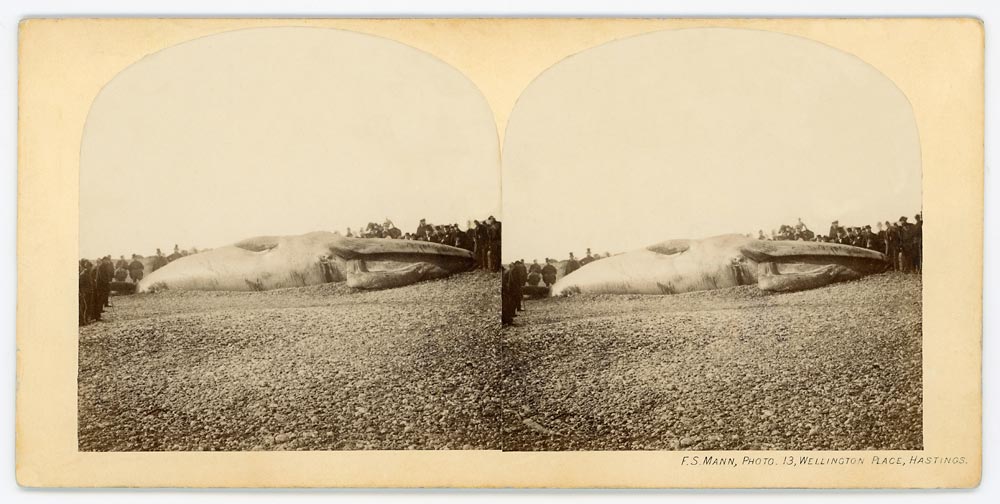

Since William Duke of Normandy landed with his troops in Pevensey Bay on 29 September 1066, just a few days before the battle of Hastings that was to make him King of England, nothing much had happened in this part of Sussex until the evening of 13 November 1865. On that particular Monday, around eight o’clock in the evening, William Richards, a coastguardsman at the Pevensey Sluice Station, noticed something floating in the water, about half a mile at sea. Thinking it was an upturned boat, he immediately reported the fact to his superior, chief officer Mr. Bussell, but the wind blowing in the direction of the land the two men soon realised that the “object” was the dead body of a whale which ended up on the beach around eleven p.m. that very night.

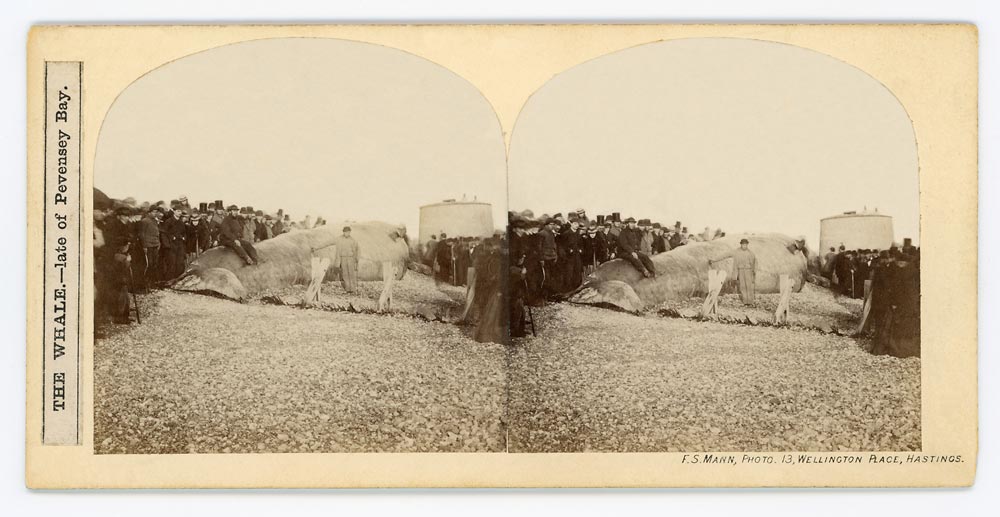

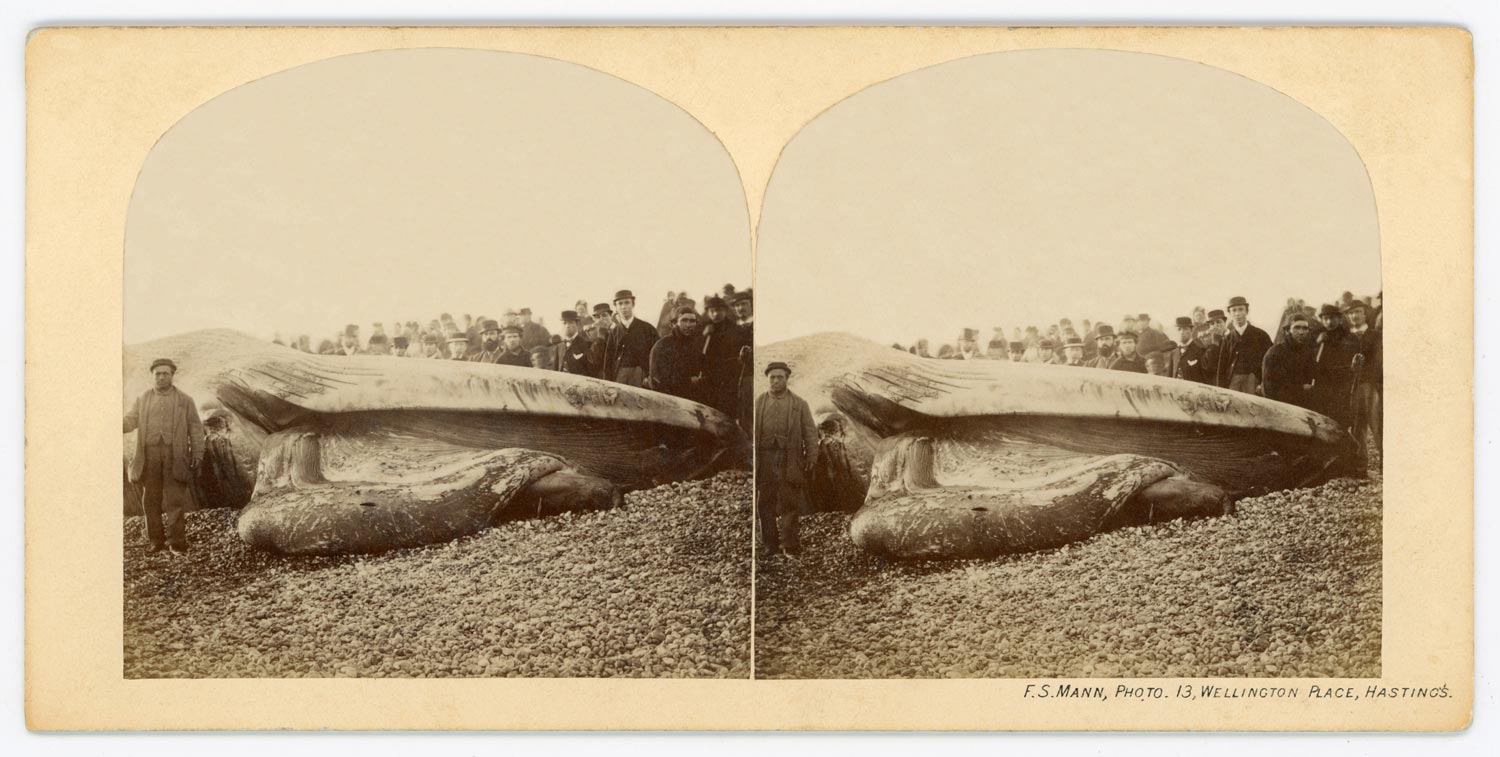

A close examination on the following day revealed it was the carcase of a bull fin whale the length of which was estimated at 70 feet (21 m) and its weight at 50 tons. The cetacean had been dead some weeks and was smelling terribly. A deep wound near its left eye, which was generally thought to have been the ultimate cause of its demise, was attributed to either a harpoon, the sharp part of a moving vessel or a fight with a sword-fish. It was conjectured the animal had died in the North Sea and had slowly drifted to it final resting place, pushed by northerly then easterly winds. The news of the gruesome discovery spread like wildfire and one of the first persons to come to the spot – half way between Bexhill and Hastings – was the Mayor of the latter place, Alderman Ross, accompanied by his Deputy-Clerk. The two men laid claim to the carcase on behalf of the Corporation of Hastings under the Cinque Ports Charter but since it was found and left below high water the Crown took possession of it – not without protest – and arranged that it be sold by auction. On Wednesday 15 November, Mr. Ody Wenham, the town crier, announced to the people of Hastings that the carcase would be sold that day at one o’clock and there was such an immediate stampede to the place where the “monster from the deep” was lying that is it was soon impossible to obtain any kind of vehicle, whether fly or carriage. The auctioneer, Mr. Groome, of Rye, conducted the sale before about 500 persons and knocked down the whale for £38 to Mr. Mark Breach, of Hastings, who was in league with a dozen fishermen and fishmongers of the area who had pooled resources to acquire the carcase, the real value of which, on account of the oil that could be get out of it, was first estimated at around £500. There was a steady flow of visitors on the Wednesday, among them some photographers from Hastings who had proceeded to the spot with their equipment in the hope that they could sell photographic cartes-de-visite commemorating this unusual event.

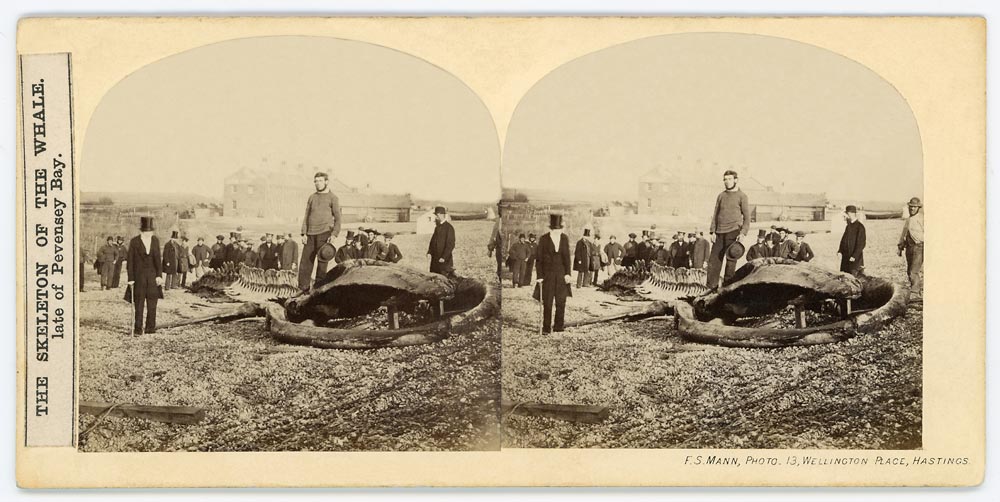

On Thursday 16 November, Mr. Frederick Stephen Mann (c. 1822-1904), photographer at 13, Wellington Place, Hastings, took some stereoscopic pictures of the whale and of the crowd around it, just before a canvas screen was erected around the carcase and its owners started recouping their investment by charging 6 pence for the privilege of examining the animal. By then, the stench was so horrendous that few people could approach the decomposing caracase without holding a handkerchief to their nose. In one of the stereograms below most of the lookers-on have momentarily hidden theirs – and probably held their breaths during the time it took Mann to operate – so that their features would be recognisable in the photograph. One of them, however, has chosen comfort over vanity and can be seen breathing through his handkerchief.

Mann, who had in turn been a grocer, a carver-gilder and a stationer, had first started his photographic career by opening a photographic depot before being becoming a professional photographer and acquiring a solid reputation as a prolific producer of stereoscopic views of Hastings and St-Leonards-on-Sea.

Another visitor to the whale on that Thursday was Mr. William Henry Flower, the Curator of the Museum of the College of Surgeons, who inspected the carcase, determined the species of the dead animal and offered £20 for its skeleton, provided its bones were not damaged during its cutting up.

On Friday 17 November, there were more visitors, despite the unpropitious weather but the sea nearly managed to claim back the carcase and the owners had to call for help to prevent the body from being washed at sea.

On the Saturday the sea was smooth again and on top of the ordinary trains two special ones with twenty carriages each and cheap fares were run from Hastings, allowing some two thousand more people to alight right at the spot – former visitors had had to walk either from Bexhill or Hastings station – and inspect the remains of the whale. In their eagerness to do so, some of the visitors threw caution to the wind and at least two accidents were reported, the first one involving people thrown out of their carriage and ending up wounded, the other victim being a doctor who hurt his shoulder when his horse fell.

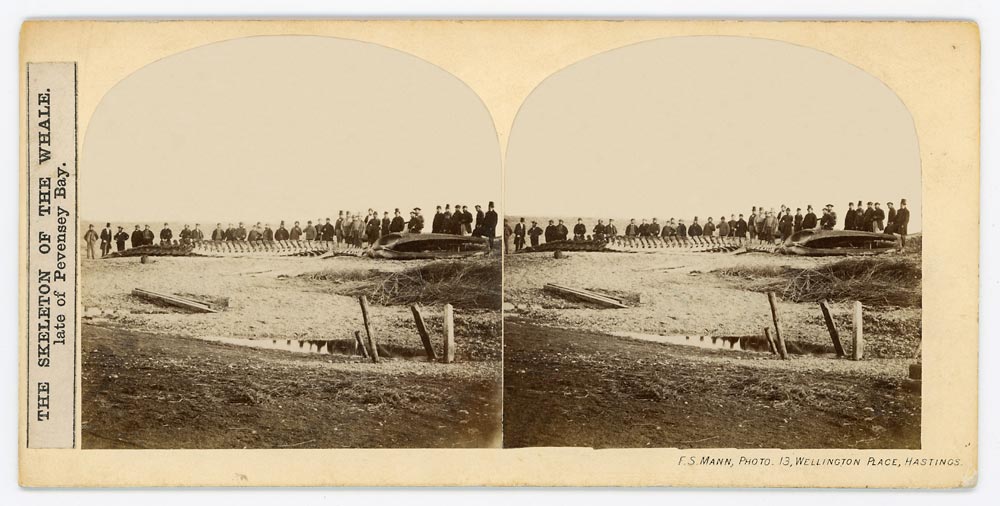

By the end of the Saturday the stench emanating from the carcass was so offensive that it was decided the animal had to be cut up on the following Monday, before further decomposition prevented the process of reducing the blubber to oil. After this was done, the skeleton was put up for auction on Friday 8 December 1865 and was bought for £50 by Mr. Harwood, of Hastings and Eastbourne. Mr Harwood had bid £75 for the “lump of bones” but was outbid seconds before the hammer went down by someone offering £80. It transpired, however, that this last-minute bidder was none other than one of the owners of the whale who had hoped to induce Mr Harwood into bidding higher. When this failed the company that owned the skeleton had to agree to Mr Harwood’s terms and accept the lower sum of £50 which he was still willing to pay.

Once in possession of what was generally believed to be “one of the finest and most perfect skeletons in Europe”, Mr Harwood lost no time in making the most of it. He had it moved to the Central Cricket Ground, Hastings and put it back together. It was photographed for the stereoscope by Frederick Stephen Mann before the following advertisement appeared on page 2 of the Eastbourne Chronicle on Saturday 23 December 1865:

CHRISTMAS HOLIDAYS

THE SKELETON of the MONSTER WHALE will be EXHIBITED for a short time in the Central Cricket Ground, Hastings.

A later advertisement, printed in the Eastbourne Chronicle from Saturday 3 February 1866 onwards gives more information about prices and viewing times:

THE SKELETON OF THE MONSTER WHALE, recently stranded at Pevensey measuring about 70 feet in length, will be exhibited every MONDAY, WEDNESDAY, and SATURDAY, from 11 till 1, and 2 till 4 o’clock.

Admission, 6d.; children, 3d.

One of the stereo cards showing the skeleton of the whale has on its back a glued paper clipping which however fails to mention the date it was published and which newspaper it was extracted from. I am sorry to say I have not been able to trace it yet but from the description it gives it must have been published around December 1865. This is confirmed by the publication in the Brighton Gazette of 4 January 1866 of a shorter piece using some passages from it.

THE WHALE SKELETON – One of the attractions for holiday keepers has been the exhibition of the skeleton of the whale lately cast ashore near Pevensey. As intimated last week, a strongly-built structure, of timber has been erected at the entrance to the Central Cricket Ground, and here the bones of this sea giant have been re-built, as in the perfect carcass. The exhibition cannot fail to be an instructive one, teaching a lesson in natural history with greater force than columns of printed words could do. A good number of persons paid the skeleton a visit on Tuesday and Wednesday ; and amongst those of them who had been attracted to Pevensey, there was a general expression of opinion that Master Whale was seen to far greater advantage, stripped of his coating and deprived of his intolerable odour, than he could be when lying on the beach. We quite concur in that opinion.

The frame teaches one, in a moment, how wonderful is that creative power which could so beautifully adapt means to the end, in the most advantageous manner. Nor can the spectator be less impressed by the consideration of the enormous strength which, animals of that class possess. The pleasure of the visit is enhanced by the description of the various parts given by the attendant. The extreme length of the skeleton is 68ft. The lower jaw bones are 16ft. 8in. long, the upper jaw 17ft. 4in. long. There are 15 ribs, the longer of which are 10 ft. 8in. and 53 vertebrae. The head and shoulders, at the point of junction of the fin bones is of immense thickness. We saw fourteen persons standing inside the cavity of the mouth, and there was then left ample room for another half-dozen. And yet the throat opening is only a small oblong aperture about nine inches by three or four inches. We would certainly advise those who would not miss an unparalleled opportunity of seeing a monster natural curiosity, to go and see the skeleton.

There are three exhibitions daily, morning, afternoon, and evening ; the hours and charges being mentioned in the advertisement in the first column. The place is comfortably fitted, and lighted by gas at night. Many of those who have visited the “raree show” have expressed their satisfaction to Mr. Harwood in complimentary terms. He is certainly entitled to credit for the excellent arrangements made in such limited time.

After a few months of exhibiting the skeleton nine times a week Mr. Harwood grew tired of it and the whale of Pevensey was sold by auction for the third time on Tuesday 29 May 1866. The auction was advertised in the Era on the 27th of May as of interest to Museum proprietors and Scientific Gentlemen:

HASTINGS, SUSSEX. – TO MUSEUM PROPRIETORS, CURATORS OF PUBLIC INSTITUTIONS, and SCIENTIFIC GENTLEMEN, PROPRIETORS of PUBLIC GARDENS, and OTHERS. – The MONSTER WHALE.

MESSRS. REEDS and SONS will Sell by Auction on Tuesday, the 29th May, 1866, at Two o’clock in the afternoon, at the Central Cricket Ground, near the Railway Station, THE SKELETON of the Monster Whale, about 70 feet in length recently stranded at Pevensey Bay, believed to be the finest and most perfect specimen in Europe.

On view the morning of the day of the sale, and further particulars of the Auctioneers, 68, George Street, and 9, Roberston Street, Hastings.

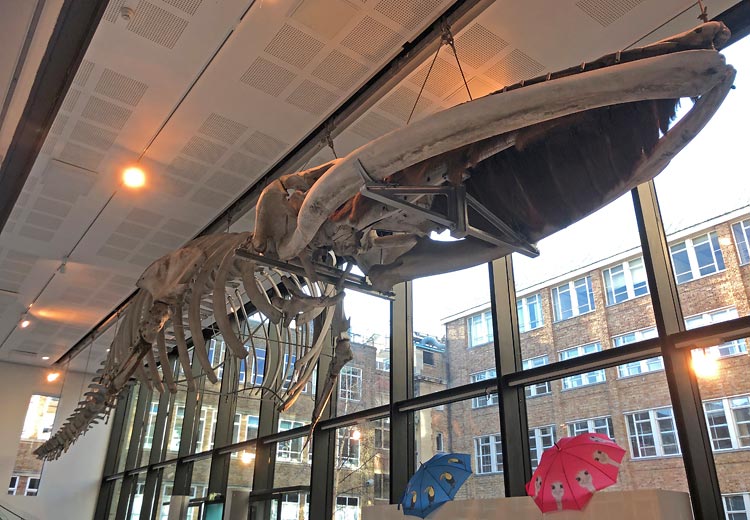

The two-ton skeleton was knocked down for £55 to Lieutenant-Colonel Shakespeare who was bidding on behalf of the University of Cambridge. This led one journalist from the Sussex Advertiser to entitle his piece “THE WHALE GOING TO COLLEGE”. The skeleton of the cetacean did not, however, end up in a college but at the museum of Zoology. It was first exhibited there in 1896, thirty years after it has been bought as it took some time to properly clean the bones and have them mounted on a metal structure capable of bearing its weight. Since 1896 it has been on public display nearly without interruption. In 1996 it was hung outside the main entrance of the 1960s museum which replaced the Victorian building and stayed there until it was dismantled prior to its being hung up in its new location, the Whale Hall of the newly refurbished Zoology Museum which opened its doors in 2017, next to the David Attenborough building.

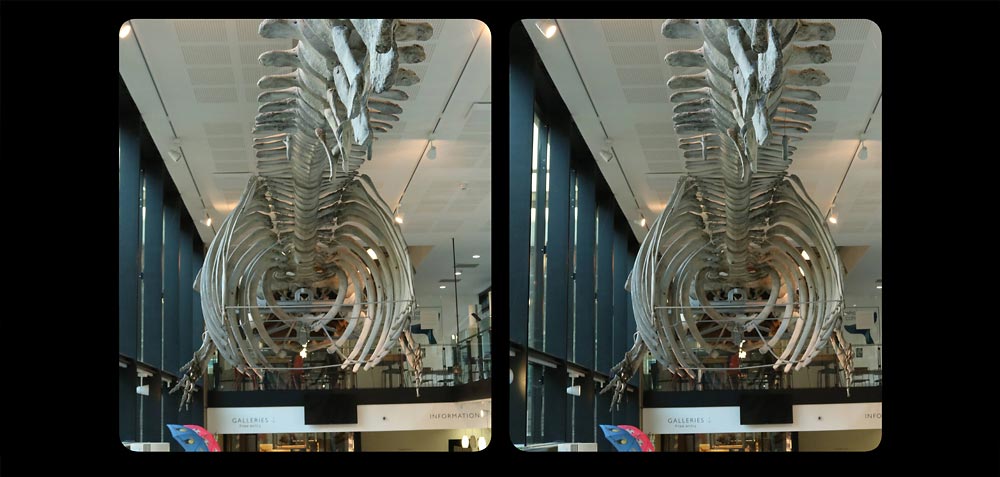

The skeleton of the Fin Whale of Pevensey Bay is the first thing visitors to the museum see as they go through the glass doors of the entrance hall where it occupies pride of place and stretches over the whole length of it. On a cold but sunny winter morning my colleague Rebecca and I drove to Cambridge for the sole purpose of paying our respects to the whale we had seen in stereoscopic photographs dating back to 1865 and take modern 3-D pictures of it to illustrate this article. The whale is the star of the museum and is used to “whale-come” the visitors and remind them to wear a face covering. There is also a Whale Café and the museum shop offers several whale-related goods, such as soft toys or ties with a whale pattern. If you are in Cambridge at some point the Museum of Zoology is well worth a visit and the staff are friendly and welcoming.

A lot of people adopt a very superior and smug attitude when speaking of the Victorians but I must say I cannot but admire their entrepreneurship and resourcefulness. If we consider the story of the Pevensey whale it is a fact that the body of the dead animal profited the local community not only financially but intellectually too and that they made the most of it. The fishermen and fish dealers who bought the carcass and the photographer who took stereos of it made some money out of it but also entertained and educated their fellow citizens, as did Mr. Harwood when he exhibited the skeleton for a period of six months or so. It is estimated that over 40,000 people saw the whale between the time it was washed on the shore and the day it was auctioned off for the third time. That is an awful lot, especially as it was long before documentaries on television could teach people about whales and show them in their natural habitat. And I am not even mentioning the huge number of visitors to the Museum of Zoology who have seen the skeleton since it was first put on display in 1896.

There is an epilogue to this story which shows that our Victorian ancestors were definitely not as wasteful as we have become. In 1970, just over a century after the carcass of the Pevensey whale was washed ashore near Hastings, another whale was cast aside on an Oregon beach. The situation was about the same as in 1865, namely that the whale was dead and stank terribly. Instead of cutting up the dead cetacean, boiling it for its oil and cleaning its skeleton for educational purposes, the people of the time decided to blow it up! Accordingly, half a ton of dynamite was laid next to the body, on the side farther away from the sea, in the hope that the blast would blow it back into the ocean. Things, however, did not go as planned. The explosion threw millions of chunks of rotten meat into the air which rained down on the onlookers and their cars, parked a quarter of a mile away from the explosion. A big piece of flesh even smashed the roof of one of the parked cars, fortunately empty at the time. The operation was a total disaster as most of the body remained untouched and had to be eventually bulldozed into the sea. It was however filmed for television by cameraman Doug Brazil and brought overnight fame to the commentator, news anchor Paul Linman. His dry humour and his choice of words1I particularly like his alliteration “the blast blasted blubber beyond all believable bounds” and his allusion to “respectable seagulls”. turned the footage into a journalistic masterpiece. In 2020, fifty years after the event, which is still talked about but which a lot of people thought was just urban legend, the footage from that day was remastered and put on YouTube, where it has already been viewed by over 13 million people. I cannot but recommend watching that three-minute video which will explain better than anything I could write why I have the greatest respect for the Victorians.

All images courtesy of Denis Pellerin.