In the Autumn 2021 issue of The Classic, we spoke to Melbourne-based artist Patrick Pound about how his vernacular photography collecting informs his art practice. In 2014, Pound installed an exhibition entitled The Gallery of Air at the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, which fused photographs from his collections with objects from the gallery’s own collection. Three years later, the National Gallery hosted Patrick Pound: The Great Exhibition, in which his collections of photographs again acted as a central point of the installation. Below, we continue our conversation about this exhibition and his installation methods, and Pound describes the way he works with photographs.

– For me, photography has always essentially been about five things: observing, noticing, recording, communicating, and sharing. This seems to me to hold from the carte de visite to snapchat, from the picture postcard or the newspaper photo to an Instagram post. I suppose my photo collecting is also about these five things. From endless looking right down to finally exhibiting. When I click buy on eBay that for me is like taking a photograph. That’s my decisive moment (laughs).

In your interview published in the Autumn 2021 issue of The Classic, you spoke a lot about the algorithms involved in the search for photographs, as well as picture postcards.

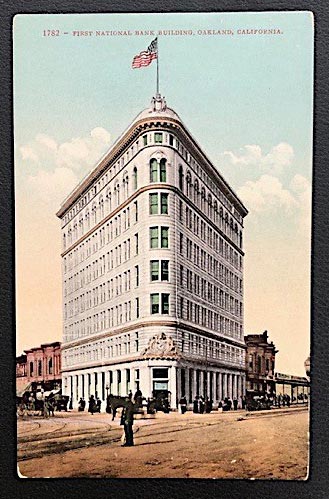

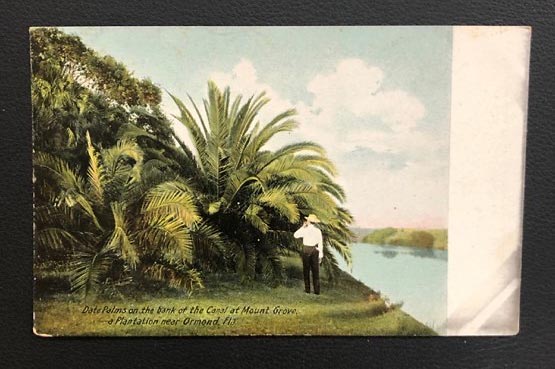

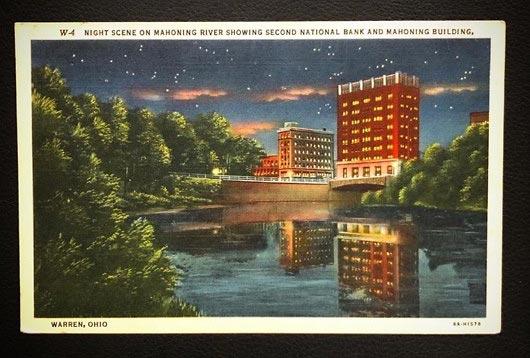

– I also work with picture postcards which collect the world in the form of categorical images for dissemination and communication. The camera, and the postcard, perhaps inevitably, reduced the world to a list of things to photograph. Whereas the patina of the search engine remains in my other collection-based artworks, in some works I rely on the search engine entirely. In the postcard work From Bank to Bank (2021), I bought numerous picture postcards featuring banks. Banks were always a major building in the town so there is a huge number available. Beginning with The First National Bank Building, Oakland, I purchased 14, to get a variety of types and times. Then this postcard search came to a fork in the road. I bought a night scene of a commercial bank that happened to be positioned on a riverbank. The search had found, and met, its match. From this folding moment, I bought a further 14 postcards of riverbanks. Here the algorithm acts as both guide, editor, and muse. Works such as these speak to the poetry of continuous failure, and the benefits of the misdirection. They speak to the fact that, in our tragicomic attempts to explain the world, we all too often reduced to collecting it.

In 2017, your photography collection was introduced to the world in Patrick Pound: The Great Exhibition, held at the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne. How did this come about?

– I suspect that the offer to undertake such a vast exhibition project that went across the entire ground floor galleries of the National Gallery of Victoria, came out of an earlier installation I made there in 2014 which was called The Gallery of Air. That installation was a surprise to us all, in that it was a conceptual art project and surprisingly, something of a crowd pleaser (laughs).

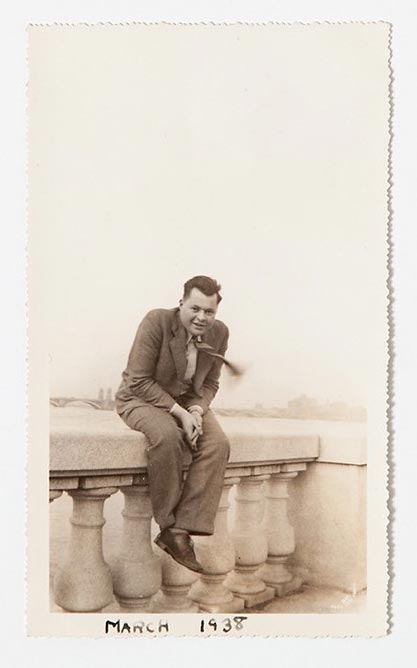

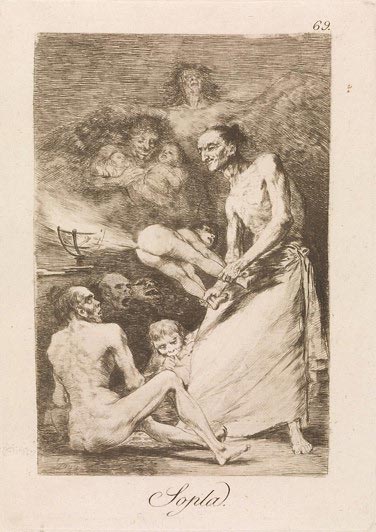

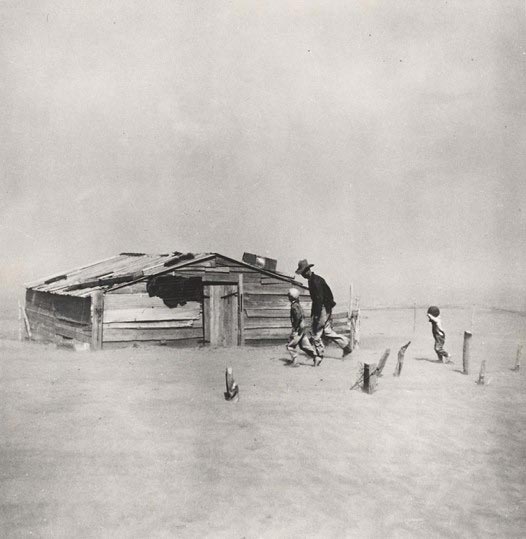

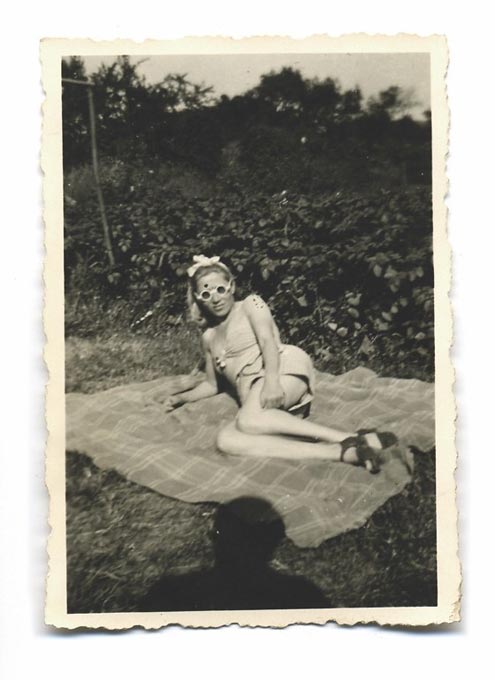

For that installation, starting from my collection of photographs that somehow held an idea of air, or portrayed air, I collected photographs and objects that somehow or other held or expressed an idea of air, in one form or another. There was everything from a discarded family snap of a man with his tie blown over his shoulder to a newspaper photograph of a new line of air conditioners. I put together hundreds of photographs and objects interweaving them with the photographs, paintings, and material objects from the vast holdings of the National Gallery of Victoria. There was everything from August Sander’s Bohemians 1922-25 portraying Willi Bongard and Gottfried Brockman smoking their cigarettes, to a snap of ………from my collection. There was Goya’s etching, Blow from 1797-8 and Arthur Rothstein’s Farmer and sons walking in the face of a dust storm taken in 1936. The air ran through them from Madrid to Oklahoma. Then there was Schenck’s Anguish with its painted sheep breathing out painted air while defending her dead lamb from Ravens, and beneath that there was my 1:1 model of a stuffed Raven next to a life-sized Resuscitation training dummy. There was everything from an asthma inhaler to a door draft excluder and a battery-operated sleeping dog whose stomach went up and down as if it was breathing (laughs).

collection of the National Gallery of Victoria

It all began with or from photography. My work got a lot more interesting when I stopped taking photos and stared buying them (laughs). Like all photographers and artists, I’m interested in the limits of representation, but rather than replicate the world with a camera, I try to put to the test the limits of how photographs and objects might behave in new company, when gathered under different circumstances. My works are essentially like cross word puzzles that have been solved for the viewer. Their task is simply to work out how each of the pieces belongs in the puzzle.

Some photographs and objects held the idea illustratively, but others required the visitor to unravel how they belonged within this constraint. Arthur Rothstein’s Dust Storm was clear enough, but Dali’s ashtray not only belonged by its referral to inhaling smoke, but by the more obscure detail that it was an ashtray produced for the first-class passengers of Air India. The air stem glass embodied the idea and the tiny model air cooler from a zephyr motorcycle held it two ways.

There was an ancient Chinese pipe and a bicycle pump. The pipe was theirs and the pump was mine. I treated all these things equally – not to say that they were of the same value, but that they were equally interesting, in the ways in which they held ideas of air. I was worried that their things might not be as interesting as mine, but they seemed to hold their own (laughs).

The Great Exhibition was an amazing opportunity. The NGV photography curator Maggie Finch, with whom I’d worked closely on The Gallery of Air was the ideal curator as she fully understood the complex rebus of my being an artist with a curatorial bent, but one who wasn’t simply motivated by ‘activating the collection’ so much as making trouble for the idea of the museum collection. Maggie also believed in my more abstract and perhaps less easily communicable or marketable idea of exploring how ideas can be embedded in photographs and things and projected on and off of them (laughs). The director Tony Ellwood and the curatorial staff across all departments were remarkably supportive and engaged in the games I set up, setting these objects a new task, and allowing us to rethink things, and for a while at least, to see them behaving differently in new contexts. Whereas the gallery’s treasures had been selected as exemplary objects of a type, in my redeployment they were given a sabbatical from that task and asked instead to stand in for an idea I brought to them.

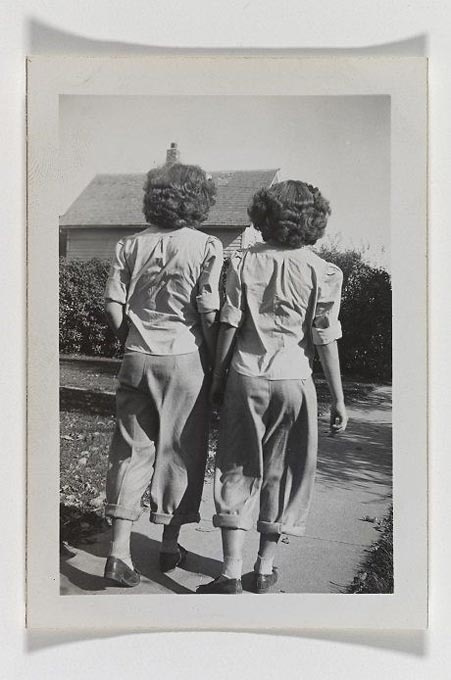

In The Great Exhibition we ended up with over 4000 photographs and objects. The registrars were saintly. More than 300 of the objects were from the gallery’s vast holdings and the rest from my photo-collections and assorted trash and treasure. Starting in the foyer, and ranging across the entire ground floor galleries, it began with a single photograph mounted standing atop a plinth and featuring a pair of twins seen from behind as if walking toward the galleries.

Then came a line of pairs of sculptures from their collection walking across the entry foyer in a parade into the galleries proper. There were pairs of figures and animals ranging across the foyer and the history of western sculpture.

In the first corridor visitors were greeted by a long line of vernacular snaps each of which featured the photographer’s shadow. The first one had my initials on his sleeve. The last had the photographer’s finger in shot as well. That’s another collection category of mine (laughs).

Then there was a room of vitrines of my collections of photographs and framed sets of photographs in categories and so on and on. In the next room there were numerous vitrines filled with my collections of photographs.

In another room there was a shelf of paintings of pairs of things and then pairs of gallery items and then my snaps of pairs and a vitrine of reflections where every photograph became a pair of itself. Finally in that room there was a monitor live searching and streaming for pairs based upon the pairs It had identified in the gallery collections. Beneath the similar images that were being thrown up from the internet, was an evolving text response to those images that was automatically generated from literature online in a poetic misreading of the parade of images flickering past. I have made several internet generated works with Rowan McNaught where he puts in play programs to perform automated searching and endless image and text generating works live before gallery visitors.

Another huge room was called: The Museum of There not There. It held hundreds of photographs and objects that variously contained or illustrated an idea of the absent made present – from a cast to a mold. There was everything from a model of the missing Malaysian airliner to a photograph of migrants on board a ship (apparently) arriving in Australia. There was everything from Dorothea Lange’s, Ditched, stalled and stranded toHiroshi Sugimoto’s photograph of a blank white glowing drive-in movie screen, and there was even the empty old frame and linen mount of a Tapies painting with the remnant ghost image of the absent work. There were unfinished etchings and restoration work in progress. There was an etching of Christ’s circumcision next to a painting of a man having a shave and a photo of a cat show competition for best neuter. There was a sculpture that was missing its helmet and a set of false eyelashes. You had to be there (laughs). The collection works keep growing over time. I have shown the Museum of there, not there on its own at Station Gallery in Melbourne since.

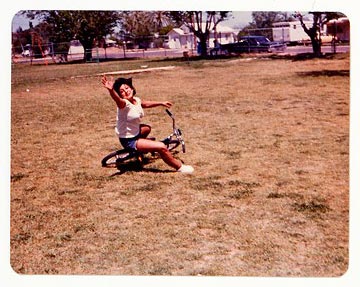

Another room had my Museum of falling with everything from a snap of a girl falling off her bike to a copy of the popular novel: ‘Snow Falling on Cedars’. There was my Museum of Holes capped off with a Barbara Hepworth as you would expect (laughs).

I called it The Great Exhibition in a nod to the crystal palace exhibition (1851) of course, but I also liked the fact that even those who really didn’t like the show still had to call it the great exhibition (laughs).

Since then, I’ve been lucky enough to work with several museum collections integrating my photo collections. For example, for Susan Bright’s terrific Photo Espana in 2019, at the Museo Lázaro Galdiano in Madrid, I worked with works from their beautiful collection that I found to hold ideas of air and my photographs that did the same. We had the air heading left and then right through my photographs and their artworks. At the City Gallery in Wellington, Aotearoa, New Zealand the wind was seen to blow through the paintings and ceramics and sculptures of the national collection borrowed from Te Papa Tongarewa and through my found photos and so on.

Can you explain how you incorporate your collections into displays? Do you let imagery guide you, fit imagery within a prescribed idea, etc.?

– Within each of my photo collections I also try and find a photographer’s shadow. I’m also trying to find a so-called wallet print in each of my categories. Then there’s also the single photos that I try to find which hold as many of my categories as possible (laughs). Say, a photographer’s shadow and thumb, of a person holding a single thing, with the wind rushing through their hair and so on.

When I exhibit my collection works, I’ve tried to develop ways of installation and display that in themselves perform the ideas. One thing I have developed is what I call the matrix hang whereby a set of photographs is found to intersect with another category constraint. I employed this method for at the Kunsthalle Mannheim where I pinned postcards and found photographs in an intersecting matrix of everything from wire photographs of 1970s terrorism to newspaper photographs of people in tears, to postcards of the Cliff House in San Francisco getting ever closer until the building catches fire, then gets rebuilt and so on for David Campany’s terrific German photo-biennale The Lives & Loves of Images (2021).

Another installation method I have gradually evolved is one where I deploy a museum object or photograph or painting that then ‘triggers’ a display of one of my constraints, and then that ‘leads’ to another museum work that holds the original constraint and a new one which is subsequently seen in my next collection display and so on. Sometimes I do this in a snowball, where each collection object gathers the constraints one by one. For example, a Daumier painting of Don Quixote reading will be hung on a wall. This will be followed by a huge collection of my photographs of all types, of all types of people reading.

This was followed by a gallery still life picture of a book on a table by an open window. The window in this painting will have a draft of air billowing through its painted curtain. This is then followed by a huge collection of my found photographs that variously hold or illustrate an idea of air. This is then followed by a gallery work that depicts sheet music captured in the wind. My following photo collection was of people listening to music, and so on. Sometimes I set things up so that there is a ricochet and other times so there is a snowball.

At the City Gallery in Wellington NZ, I hung an entire show in the form of a palindrome. The gallery walls were arranged in perfect symmetry. You had to enter from the middle. There was a central vitrine with photos of reflections so that whichever side of the vitrine you viewed them from, they appeared as if up the right way. Then it didn’t matter which way you went as each wall held a mirror collection of its opposite. From men on the phone if you went left to women on the phone of you went right. Then there were photos featuring a single number from 1-26 and in an opposite gallery 26-1; then a-z and z-a, and on and on, in a labyrinthine pun on the positives and negatives of capturing the world with cameras. At each end you found a collection of photographs and museum objects of people and things pointing. That collection is called: The point of everything (laughs).

While my work looks very analogue it deliberately plays on the idea of an unthinking algorithmic way of searching and sorting that also relies on the failure of such systems to order or explain the world. I prefer the miss-step to the perfect marching band; I prefer the poetic folly of the failed attempt. You could say my photo collections are in themselves like those romantic architectural follies, or actual ruins for that matter. That’s it they are ruins after all, like Benjamin’s Arcades and Soane’s house museum of architectural fragments (laughs). Museums often bureaucratise aesthetics, and archiving artists tens to aestheticize bureaucracy. I’m stuck filing away in between.