To take a photograph is to slice and dice the world.

The camera frames the world, dividing it into legible, palatable slices. The camera has a say in the shape of things. Then the photographer chimes in. Photographers are, from the outset, picture framers.

The photograph gives shape to our view of the world. The limits and edges of those views have unique photographic qualities, and expressive possibilities, and unintended consequences aplenty.

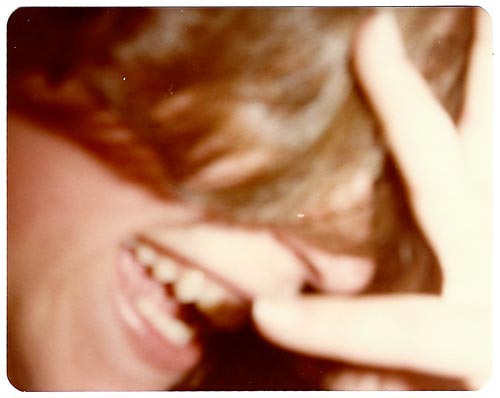

Every photographer is faced with an array of choices. Decisions need to be made. Where to point and shoot. What to include and what to leave out. How the photograph’s edges will work alongside the images they contain. Then, of course, there is the matter of the things that sneak into frame; and those that might get cropped, as if by a guillotine.

To step closer is to crop further. To step back is to widen the view. The camera swallows the world with its “hungry eye”. The zoom lens takes the frame in and out, chewing things up as so much pictorial fodder. We have come to take this for granted, as a condition of photographic seeing and recording. Some photographs remind us of the peculiar frames that photography wealds; takes for granted, and relies upon.

However, to take (or make) a photograph is not simply to determine the content of one’s pictures but to decide upon the way the picture’s edges behave in relation to that content.

Sometimes when I look at a photograph, I wonder what is happening beyond the frame. Is there a hidden mother supporting that precariously seated child? Has her support been kept out of frame? Is the rest of the house that tidy? Is the house next door on fire too?

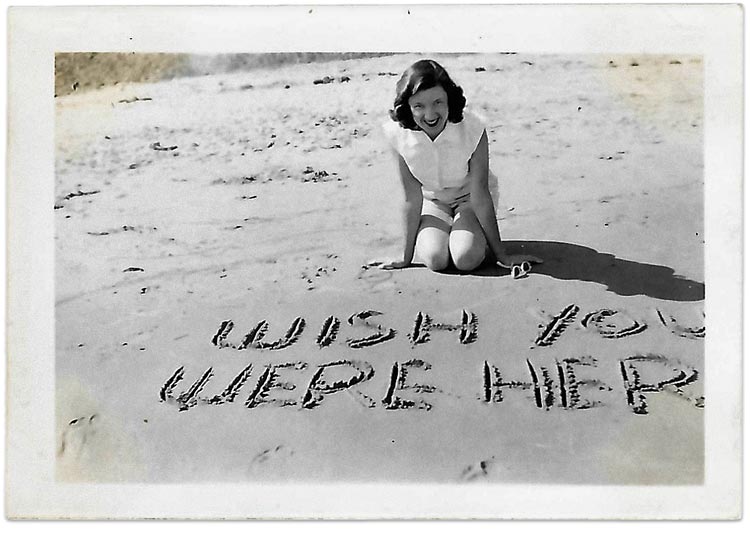

Most of the time, if the photographer has done their job, we are only really concerned with what is in view, with what the photographer has decided to frame up for us. Sometimes that framing is essential to the experience and the meaning of the photograph. Sometimes, it seems as if the edges of the image are not so much chosen as they are the mechanical decisions of the camera; no AI here, but simply a peculiar, and exquisite, machine limit. In their amateur ways, vernacular snaps occasionally seem to rethink the frame by ignoring it. These inadvertent compositions, with their unusual edges are collectors’ treasures. They are accidental Friedlanders, awaiting our discovery.

The world is cut into shapes by her photographers. The photograph’s edges are sometimes unpredictable. Before the single-lens reflex made the photographer’s framing of a scene more accurate the edges of the image were more-or-less a guesstimate. Experienced amateurs and professional photographers got to know the approximate field of inclusion, differing from the camera’s field of vision. For others near misses were a fact of life.

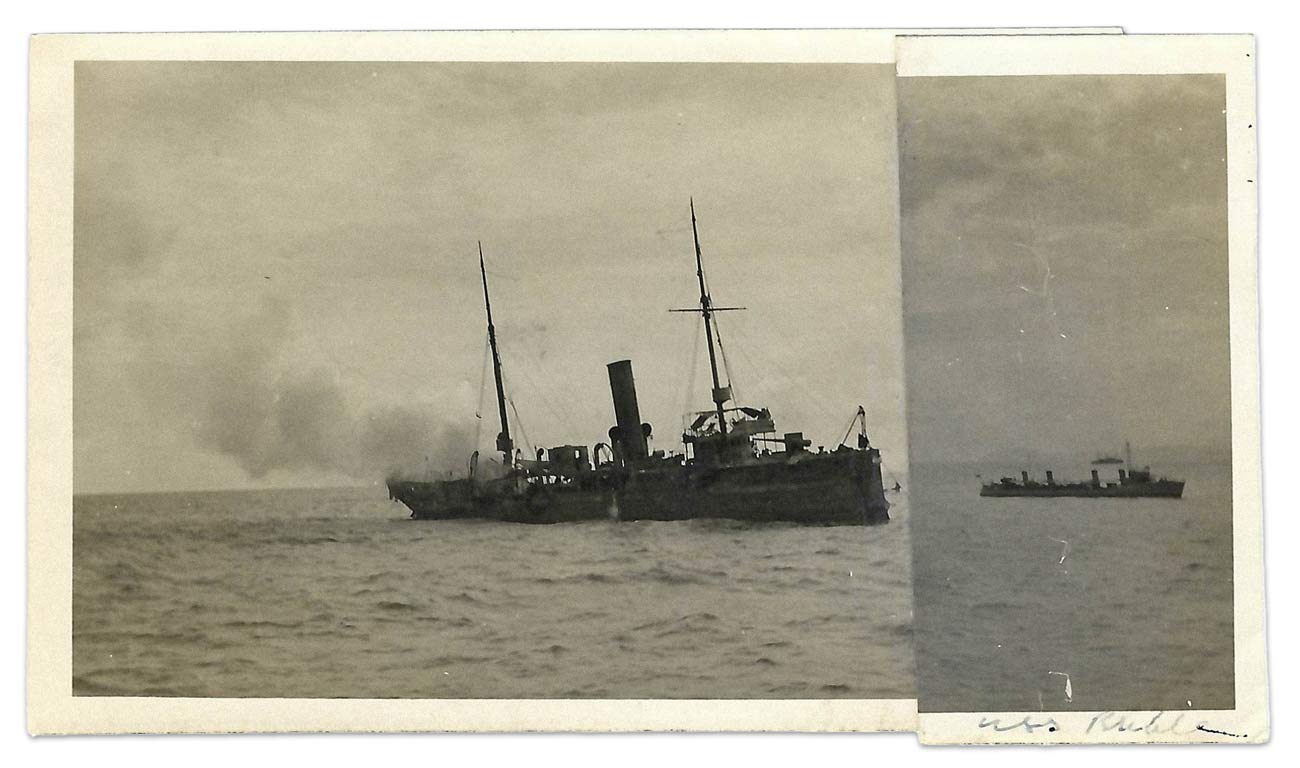

On other occasions the camera simply failed to take it all in. The photograph needed another frame, to extend the view.

Then again, for those photographs that were not printed out “full frame” the edges of the image could be redetermined of course. A scene could always be cropped, but once that image was captured on a negative, or a positive transparency, the extent of the “frame” was (typically) set. These characteristics led to types of images that simply were not possible before photography. Notably, with the invention of photography, and these new framing machines and their quirks, the Impressionist and Post-Impressionist painters adopted these camera views of the world, with artists like Degas, and Caillebotte cropping their painted figures at the edges of their paintings as if they had no choice in the matter. This was after all the new reality, or reality seen anew.1For an excellent account of this, see: Linda Nochlin, The Body in Pieces: the Fragment as a Metaphor of Modernity, Thames & Hudson, 1995. Body parts were seen entering and exiting the frame like passers-by from an abattoir. It seems to me that a truth to material information (in the form of photographic records), predated and almost anticipated the truth to materials, as a truism of the avant-garde.

When it comes to the idea of the photographic frame: firstly, there are the decisive edges of the picture, its boundary fences which are (typically) determined by the photographer, deliberately, intuitively, or unconsciously. Then of course, there are the frames applied later to those pictures, by photographers, studios, capital F Framers and others, all after the event of the photograph. Each of those frames, an addition, intended as an improvement, a protective support, a finishing ‘touch,’ and a point of interest in and of itself. Those frames are made or applied in retrospect. They range from the little photobooth paper frame to set off a sitter’s face, and allow it to sit on a shelf, to the contemporary artist’s box-frame with deep spacers, to effectively increase its presence and ‘wall power’ as an object, and an artwork.

Consciously or otherwise, there is then a huge range of framing devices that photographers bring to their pictures, both before and after their taking. In this, photographers are image and object makers. The photographer’s selected fragment of the world is just that, a segment with framing edges. Then the resulting photograph, the material prints are, both pictures and physical objects. It seems to me that the photograph is always something of a contest between the subject and the medium.

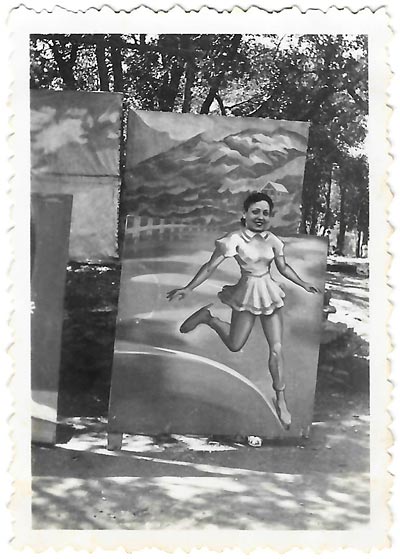

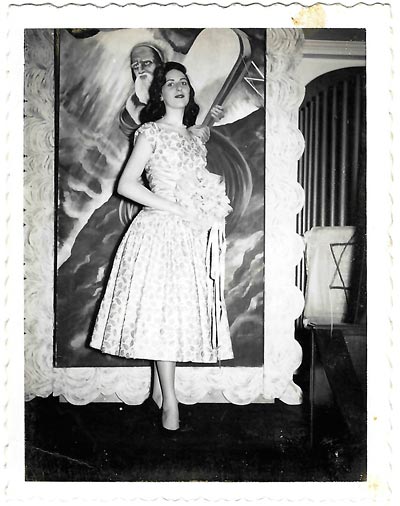

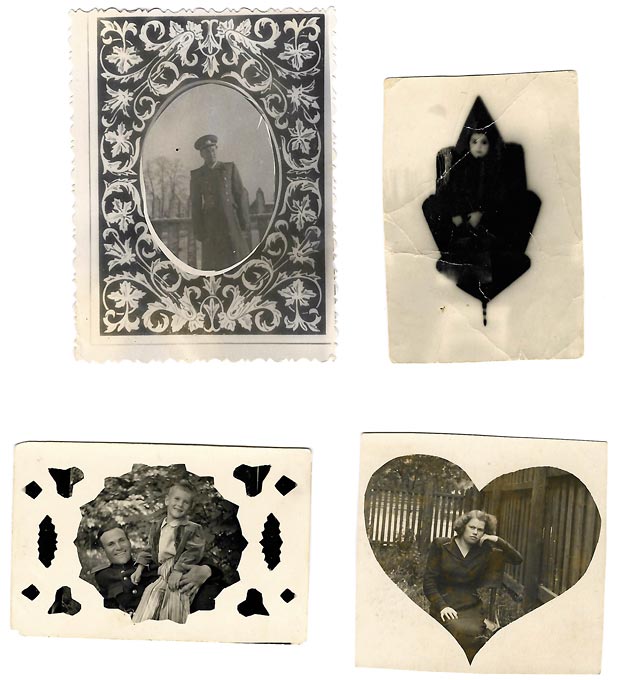

The most common “meta-photographic” framing, is the type of frame whereby the print itself incorporates that (usually paper white) frame, from simple border edges, to machine cut ornate borders, which are themselves the same stuff as the photograph – the very same paper stock, shining away or sitting back in matt muteness. These start with the creamy white borders of the family snap, and the more elaborate cut-out edges with their repetitive flourish patterns that fancify the image ready for the awaiting album page. These “frames” see photographs behave quite differently to the fully bled, “full frame” image.

Borders are frames that the amateur has become accustomed to. Yesterday I spent a day shuffling through thousands of amateur snaps, the vast majority of which came with borders of various kinds: little cream frames. That night I picked up a recent book production of Stephen Shore’s Steel Town.2Stephen Shore, Steel Town, Mack, 2021. Each photograph was reproduced hard edged. No frame. No border. Just a cut-out rectangle of the world reduced for the page. I became hyper aware of this cutting out, as a highly artificial device that the machinery of photography had turned into a normal state-of-affairs. This technological vision, was once radical, with its cropping of the visible, experienced, world. This typical artful cropping, whereby the pictures sit on the page as a series of pictures, turns those pictures away from the material qualities of the printed-out every-day amateur photograph. The book becomes the material platform, and the picture a screen, much like that of the digital turn, where the image is so fundamental to our seeing that we see through the facticity of the photograph, and via the image as if it were just another lens.

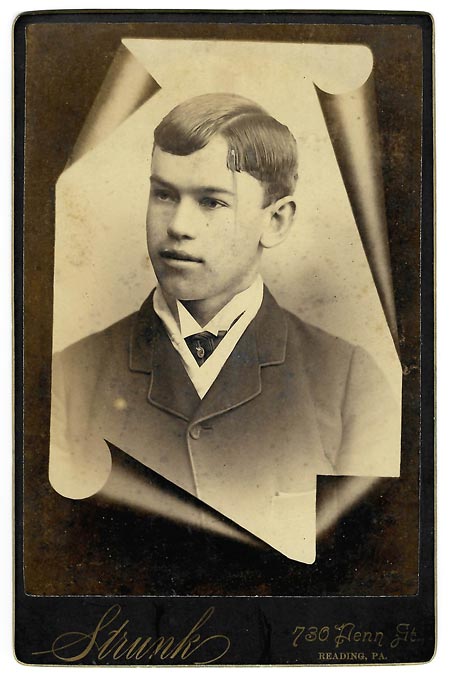

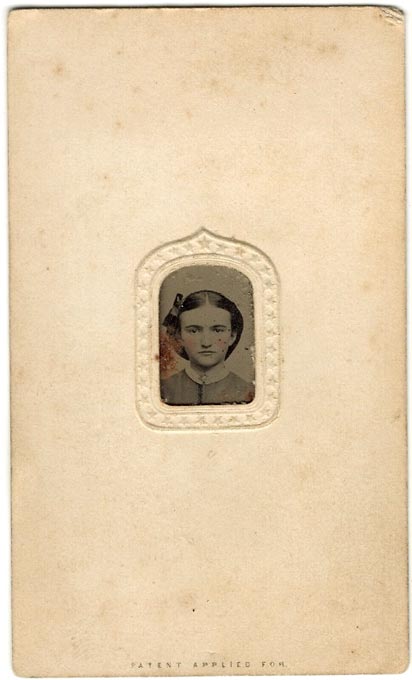

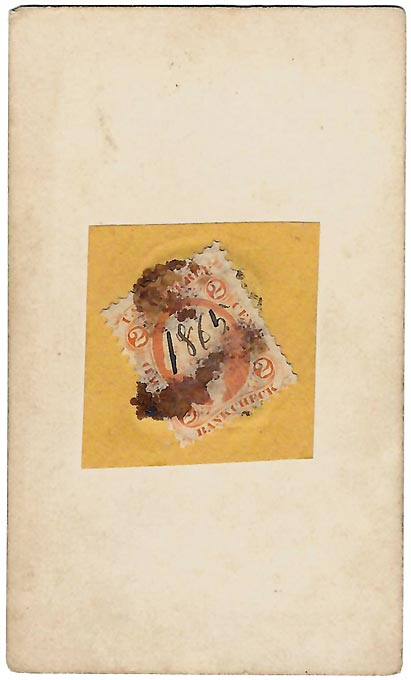

Printed out vernacular photographs were once often made with additional framing supports in mind. Once there were mounts which provided “frames” that surrounded the pasted image. Sometimes they supported it, ready for display or distribution. The carte-de-visite and the cabinet card being two typical mass-produced examples. Collectors now sort out these unused frames in waiting.

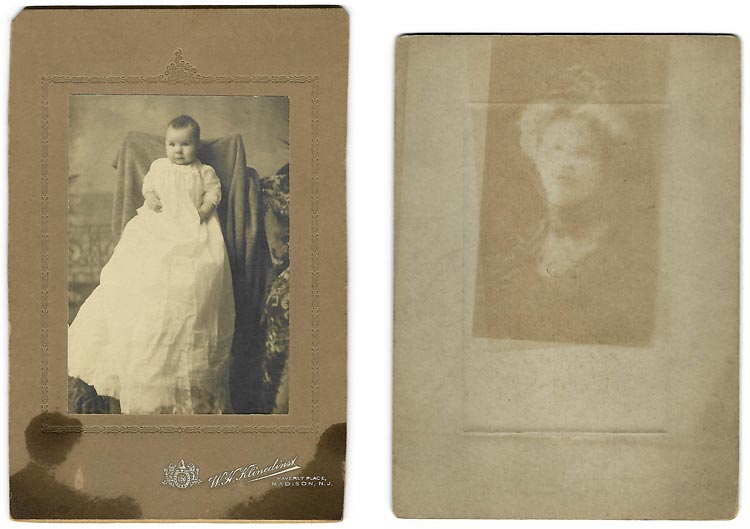

Sometimes the frame seemed to include the viewer. Here, on the left, this photograph of a baby (probably supported by a hidden carer), sees a pair of stains take up residence as the image’s audience. And then, on the right, a ghost of another photograph appears on the reverse of the card frame of yet another photograph.3The photographic artist, Andy Mattern has made works redeploying this found phenomenon in platinum prints, which he recently exhibited at the Oklahoma State University. OSU Museum of Arts, Some Recent Apparitions: Andy Mattern, Jan 16 – March 23, 2024.

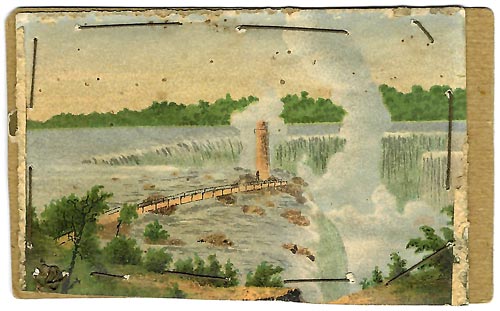

Victorian photograph albums often came with cardboard pages that were constructed of double cardboard sheets making for shapely framing windows, often with decorative printed scrolling, and even rendered scenery, anticipating the portrait photographs to come.

Then there are proper frames. These are frames that have been applied to the photograph. They are a later addition to the thinking process. They are protective and (hopefully) flattering. They set off the image. They set it alight. They also allow the photograph to be hung, or to be stood up on the bureau, the mantle, or the piano, as if a constant reminder of the subject they contain. They take the modest domestic document and elevate it to a picture befitting “the good room”.

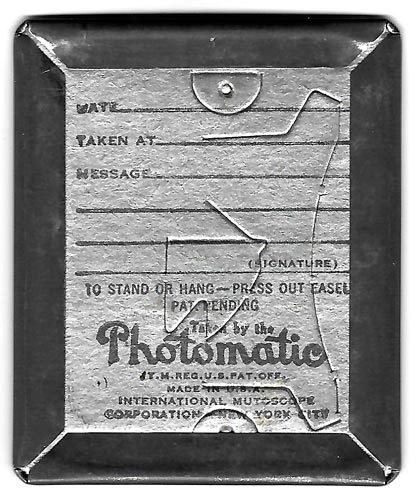

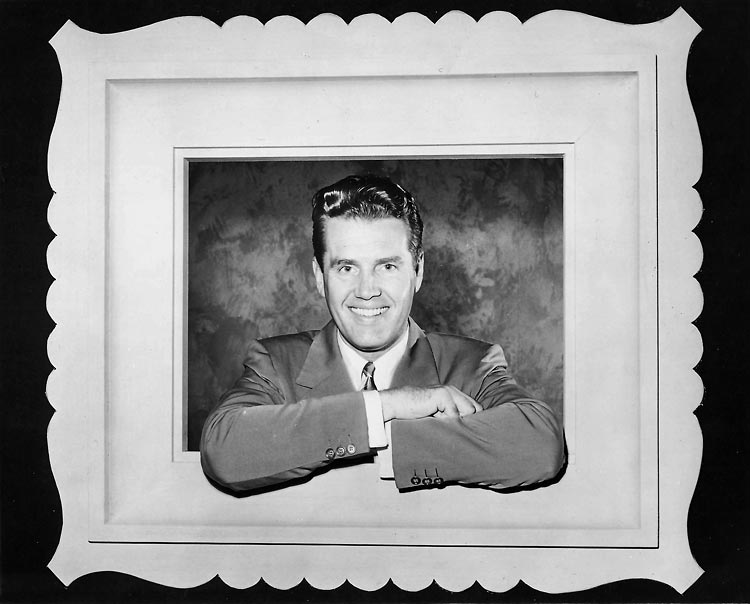

One of my favourite examples of this modest protection-promotion tactic is the photobooth portrait that came compete with a readymade frame. These photomat frames vary greatly. There is the lovely little cardboard pre-cut fold out frames, ready for the image to immediately be displayed. Then we have the printed paper linen effect frames, elevating the little photos, rendering them gift worthy. These modest improvements set the sitter off with a tidy material edge turning the images into trinkets and keepsakes.

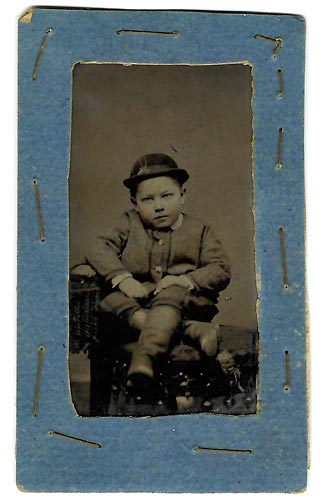

Other photobooth pictures were sold with raw tin or coloured metal frames. They were part of the package. Early Tin Type images, are also often found in an array of fitted frames. More formal studio photographs often came with a practical paper frame. These mounts were part frame, part advertisement.

These paper, and cloth, and tin, surrounds et al, actively partake in the construction of a photograph’s presence in the world and the way the photograph goes on to function, and perform in the world; how it might be used and how it acts, and the meanings it might attract and project.

Then of course, there are the so-called folk-art frames made with loving care and dedication peculiar to an individual photograph and its subject. These crafted frames often seem purpose-built to turn the photographs into domestic quasi-votive objects. Together, photo and frame, become almost talismanic. They are marinated in the deeply personal. As material remnants, they survive as sentimental souvenirs of what they once meant as objects for both their sitter and their maker. Like the lock of hair of a deceased child they seem to almost resuscitate a piece of what it means to be human.

These homely objects range from the sewn and the threaded to the woven and the carved, and include everything from interwoven sticks to Mexican fotoesculturas, with their hand-coloured photographs becoming apiece with ornate wooden supports and frames. My piling them together here is not to imply that they have the same meaning in their different cultural contexts, but to group them as deeply personal and diverse framed photographic objects of the loving kind.

This also brings-to-mind the different ways in which different cultures might distinctively display and deploy their framed photographs. Those contexts are of course yet another type of framing, from the portrait photographs in the Māori marae (meeting houses) of Aotearoa (New Zealand), to the Italian tombstone photographs in their glass enclosures that one especially sees in Italy and her diasporic cemeteries across the globe.

When thinking of photography and framing, we must let the exceptions have a look in.

Once in a while we find photographs that feature frames within frames. Here the frames are both subject, and material outcome. While we are getting “meta” we must include photographs of framed photographs.

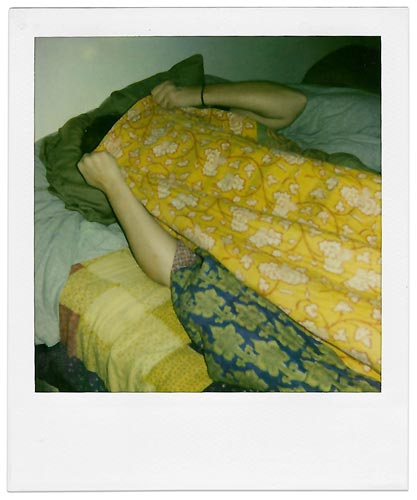

There are also photographs that employ a mask in the printing process, that make for playful, expressive, and shapely little “internal” frames. And, speaking of shapes, let’s not forget the rounded corners of those irresistible colour Kodak photographs, which remind us that the shaped piece of paper is itself a frame, cutting out pieces of the world in shapely portions, or the polaroid SX70 instant, paper “framed” photographs.

Occasionally some photographs even seem to escape their imposed frames, as if in some little act of defiance. And then sometimes we find frames sewn on to photographs fixing them for good.

Sometimes hand-crafted frames make for more interesting material objects when seen from behind. Here, photography is seen to bend back on itself, and the hand of display takes over from the recording machine. It is the personal touch that picks out these photographs.

And, finally, we might give the last word to those newspaper photographs that “break” the frame in-order-to make room for the printed text to come. After all, even photographs sometimes have-to make way for words.

All images courtesy of Patrick Pound